Intraaortic Balloon Counterpulsation

Olcay Aksoy

I. INTRODUCTION.

Intraaortic balloon counterpulsation (IABC) is usually used to support hemodynamics in cardiogenic shock and to relieve medically refractory ischemia in patients with severe coronary disease. The duration of support with an intraaortic balloon pump (IABP) is typically short, because multiple complications can develop in patients treated with IABC. Patients should be carefully selected for receiving IABC therapy and should be closely monitored in a critical care setting while the IABP is in place.

II. INDICATIONS

A. Cardiogenic shock

1. Bridge to revascularization.

IABC provides temporary hemodynamic stabilization in patients with cardiogenic shock caused by acute myocardial infarction (MI). Hospital survival rates for cardiogenic shock with balloon pump support alone without revascularization are poor (5% to 20%). Early revascularization with percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty (PTCA) improves survival rates in cardiogenic shock caused by acute MI.

a. In the Global Utilization of Streptokinase and Tissue Plasminogen Activator for Occluded Coronary Arteries I (GUSTO I) trial comparing fibrinolytic regimens for acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), PTCA was the only factor associated with a lower 30-day mortality rate in 2,972 patients with cardiogenic shock.

b. In addition, early placement of an IABP in this cohort of patients was associated with lower 30-day and 1-year mortality rates.

c. Cardiogenic shock and hemodynamic support during or after percutaneous coronary intervention are the primary reasons for IABP placement in more than half of all patients treated with IABC. IABP placement is an ACC/AHA class I recommendation in patients with STEMI presenting with cardiogenic shock when shock is not quickly reversed with pharmacologic therapy. The IABP in this setting is a stabilizing measure for angiography and prompt revascularization.

2. Bridge to a tertiary center.

Thrombolytic therapy alone in patients with cardiogenic shock is less successful than mechanical reperfusion. However, the addition of IABC to thrombolysis can improve outcomes in patients with cardiogenic shock. In 46 patients with acute MI and cardiogenic shock treated at community hospitals without angioplasty capabilities, simultaneous treatment with thrombolysis and IABC was associated with an improved 1-year survival rate (67% vs. 32%) and successful transfer to a tertiary facility for revascularization when thrombolysis failed.

B. Acute MI treated with catheter-based reperfusion.

The benefits of IABC in patients with acute MI without cardiogenic shock treated with catheter-based reperfusion are uncertain.

1. In a randomized trial of 182 hemodynamically stable patients who underwent direct PTCA for acute MI, prophylactic IABC for 2 days after the procedure

reduced recurrent ischemia and reocclusion of the infarct-related artery but had no effect on survival or reinfarction.

reduced recurrent ischemia and reocclusion of the infarct-related artery but had no effect on survival or reinfarction.

2. In the Primary Angioplasty in Myocardial Infarction II (PAMI II) trial, 437 high-risk patients (age > 70 years, multivessel coronary disease, reduced ejection fraction, vein graft disease, or persistent ventricular arrhythmias) treated with direct PTCA for acute MI were randomized to ± 1 to 2 days of IABC after PTCA. Patients treated with IABC had a slight reduction in recurrent ischemia but had no reduction in mortality, reinfarction, or infarct-related artery reocclusion. Thus, hemodynamically stable patients with acute MI treated with catheter-based reperfusion are not likely to benefit from IABP support after the intervention.

C. High-risk percutaneous revascularization.

Patients at high risk for complications during percutaneous revascularization include those with unprotected left main coronary disease, left ventricular dysfunction (ejection fraction < 40%), the target vessel supplying > 40% of the myocardial territory, or severe congestive heart failure (CHF). Placement of an IABP in these high-risk patients affords the operator a longer duration of ischemia during balloon inflation and wire manipulation.

1. In a study of 219 patients undergoing unprotected left main trunk stenting, elective IABP placement was associated with fewer intraprocedural major adverse cardiac events, including combined end points of severe hypotension, MI, need for urgent bypass surgery, and death.

2. Although there are no specific recommendations for when to use IABC during high-risk coronary interventions, improved percutaneous revascularization techniques with coronary stents and adjunctive glycoprotein IIb/IIIa receptor antagonists have reduced the need for prophylactic IABP placement in high-risk patients.

D. Mechanical complications of acute MI.

Acute mitral regurgitation (MR) and ventricular septal defect are devastating complications of acute MI and frequently cause rapid deterioration progressing to cardiogenic shock. An IABP should be placed before surgical repair in patients with hemodynamically significant MR or ventricular septal defect after an MI. Placement of an IABP in the setting of STEMI and secondary acute mitral valve regurgitation is an ACC/AHA class I indication. Similarly, insertion of an IABP and prompt surgical referral are class I recommendations.

E. Refractory unstable angina.

Patients with severe coronary disease who have refractory ischemia or hemodynamic instability show dramatic improvement when IABC is used before revascularization. The ACC/AHA clinical guidelines assign a class I recommendation in STEMI patients and a class IIa recommendation in Unstable angina/Non ST segment elevation myocardial infarct (UA/NSTEMI) patients for IABP placement in the setting of severe ischemia that is continuing or recurs frequently despite intensive medical therapy. In the setting of STEMI, refractory pulmonary congestion carries a class IIb recommendation for IABP placement.

F. Weaning from cardiopulmonary bypass/postoperative pump failure.

Patients with severe left ventricular dysfunction or those with prolonged runs on cardiopulmonary bypass can be difficult to wean from bypass after open heart surgery because of stunned myocardium from prolonged cardioplegic arrest. For these patients, IABP support improves hemodynamics and facilitates weaning from cardiopulmonary bypass.

G. End-stage cardiomyopathy/bridge to cardiac transplantation.

An IABP improves cardiac output and lowers filling pressures in patients with dilated and ischemic cardiomyopathy. It can be used for hemodynamic support before cardiac transplantation.

1. Disadvantages of prolonged IABP support in patients awaiting cardiac transplantation include a high risk of infection and the need for continuous bed rest.

2. However, with improved inotropic therapy and implantable left ventricular assist devices for patients awaiting cardiac transplantation, IABC is now used infrequently for prolonged mechanical support in patients with end-stage cardiomyopathy.

H. Refractory ventricular arrhythmias.

Incessant ventricular tachycardia compromises left ventricular filling, reduces stroke volume, and causes or exacerbates ischemia. IABC improved hemodynamics, lessened ischemia, and controlled refractory ventricular arrhythmias in 86% of patients in a large case series. Placement of an IABP support in patients with STEMI and refractory polymorphic ventricular tachycardia carries an ACC/AHA class IIa recommendation.

I. Support during noncardiac surgery.

Patients with severe coronary disease, recent MI, and severe left ventricular dysfunction are at high risk for cardiac complications when they undergo noncardiac surgery. Case reports have demonstrated that high-risk patients are stabilized hemodynamically and have acceptable postoperative outcomes when prophylactic IABP support is used during and after noncardiac surgical procedures.

J. Decompensated aortic stenosis can be managed with temporary IABP support to improve the stroke volume and reduce the transvalvular gradient before aortic valve replacement. In a study of 25 patients with severe aortic stenosis and cardiogenic shock, IABP support was associated with prompt improvement in cardiac output and filling pressures, allowing stabilization of patients before surgery. However, because aortic insufficiency often accompanies severe aortic stenosis, careful monitoring early after initiation of IABC is recommended to ensure that aortic insufficiency is not worsened by the balloon pump.

III. CONTRAINDICATIONS

A. Aortic dissection.

Any type of aortic dissection precludes IABP use because of the potential of the balloon catheter to extend the dissection and to worsen ischemia of a peripheral vascular bed that may be involved by the dissection.

B. Abdominal or thoracic aneurysm.

Using IABP with an abdominal or thoracic aneurysm can precipitate an acute aortic dissection, dislodgement of atheroemboli, or aortic rupture, so the presence of an aneurysm is a contraindication to IABP use.

C. Severe peripheral vascular disease

1. The majority of the complications of IABC are caused by vascular insufficiency in the accessed leg because of the large size of the balloon sheath and catheter and the concomitant presence of peripheral vascular disease in patients who typically need IABC. In the past, the IABP catheters had been available only in 8F and 9.5F sizes; however, with improving equipment, 7F catheters have been introduced, and these have diminished the rate of complications due to obstruction of arterial flow.

2. Limb ischemia and threatened limb viability can occur when peripheral perfusion is compromised by the balloon catheter and sheath. The IABP catheter can be inserted without a sheath to reduce the diameter of obstruction in the iliac vessels, but in patients with tortuous aortoiliac vessels, sheathless IABP insertion can be difficult.

3. Thus, severe peripheral vascular disease is a contraindication to IABP insertion, depending on the necessity of IABP support and the degree of vascular compromise.

D. Descending aortic and peripheral vascular grafts

1. Prosthetic descending aortic grafts and iliofemoral vascular grafts are relative contraindications to IABC. Consultation with a vascular surgeon is recommended before attempting balloon pump insertion in these patients.

2. Iliac artery stents are not an absolute contraindication to IABP placement. However, passage of the guidewire and balloon catheter through the stent must be performed under direct fluoroscopic guidance.

E. Coagulopathy or contraindication to heparin

1. The balloon catheter is thrombogenic, and intravenous heparin is commonly given while the IABP is in place to prevent the development of thrombi on the balloon surface. Patients with a contraindication to heparin, such as those with prior heparin-induced thrombocytopenia, can be anticoagulated with alternative agents such as direct thrombin inhibitors like bivalirudin.

2. After cardiac surgery, heparin can be avoided because of the increased risk of intrathoracic bleeding, but IABP support in such patients is usually of short duration. In nonsurgical patients, if an anticoagulant cannot be given or if a severe coagulopathy exists that could precipitate bleeding at the access site, IABC is discouraged, but it could safely be undertaken for a short period.

F. Moderate to severe aortic insufficiency.

By inflating during diastole, the IABP can worsen aortic insufficiency when blood is displaced to the proximal aorta. No consensus exists as to what degree of aortic insufficiency absolutely contraindicates IABP use. Therefore, careful monitoring of patients with aortic insufficiency who absolutely need IABP support is recommended.

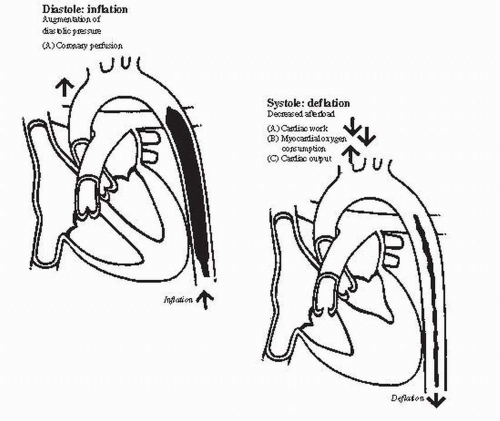

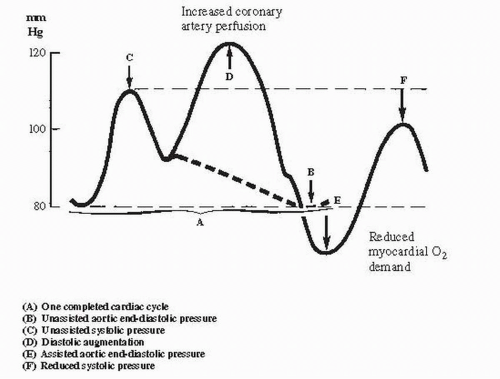

IV. HEMODYNAMICS OF BALLOON PUMP FUNCTION

A. Decreased afterload

1. As systole begins, the intraaortic balloon rapidly deflates and creates a negative pressure in the aorta, which reduces afterload and improves forward flow from the left ventricle. Afterload reduction occurs because the aortic end-diastolic pressure is reduced, resulting in an increase in cardiac output of approximately 20% and a decrease in the mean pulmonary capillary wedge pressure of approximately 20%.

2. The overall hemodynamic benefit of IABP appears to be a reduction in left ventricular wall stress from decreased filling pressures and decreased afterload, which in turn improves stroke volume and cardiac output (see Figs. 63.1 and 63.2).

B. Augmented coronary perfusion

1. When the balloon inflates during diastole, it displaces blood to the proximal aorta and augments aortic diastolic pressure and, thus, coronary perfusion pressure. The augmentation of coronary perfusion pressure is more dramatic when systemic hypotension is present (see Figs. 63.1 and 63.2).

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|