Inflammatory and Valvular Disorders

Just the facts

Just the factsIn this chapter, you’ll learn:

♦ disorders that affect the lining or valves of the heart

♦ pathophysiology and treatments related to these disorders

♦ diagnostic tests, assessment findings, and nursing interventions for each disorder.

A look at inflammatory disorders

Inflammatory cardiac disorders include endocarditis, myocarditis, and pericarditis. With these conditions, scar formation and otherwise normal healing processes can cause debilitating structural damage to the heart.

Endocarditis

Endocarditis is an infection of the endocardium, the heart valves, or a cardiac prosthesis. It typically results from bacterial invasion. In intravenous (IV) drug abusers, it may also result from fungal invasion.

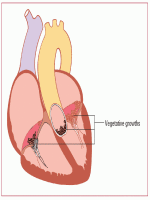

Green growth

This invasion produces vegetative growths on the heart valves, the endocardial lining of a heart chamber, or the endothelium of a blood vessel that may embolize to the spleen, kidneys, central nervous system (CNS), extremities, and lungs. (See Effects of endocarditis.)

|

|

Type talk

There are three types of endocarditis:

Acute infective endocarditis usually results from bacteremia that follows septic thrombophlebitis, open-heart surgery involving prosthetic valves, or skin, bone, and pulmonary infections. This form of endocarditis also occurs in IV drug abusers.

Acute infective endocarditis usually results from bacteremia that follows septic thrombophlebitis, open-heart surgery involving prosthetic valves, or skin, bone, and pulmonary infections. This form of endocarditis also occurs in IV drug abusers. Subacute infective endocarditis typically occurs in individuals with acquired valvular or congenital cardiac lesions. It can also follow dental, genitourinary, gynecologic, and gastrointestinal (GI) procedures.

Subacute infective endocarditis typically occurs in individuals with acquired valvular or congenital cardiac lesions. It can also follow dental, genitourinary, gynecologic, and gastrointestinal (GI) procedures.Treat, or else

Untreated endocarditis usually proves fatal; however, with proper treatment, 70% of patients recover. Prognosis becomes much

worse when endocarditis causes severe valvular damage (leading to insufficiency and heart failure) or when it involves a prosthetic valve.

worse when endocarditis causes severe valvular damage (leading to insufficiency and heart failure) or when it involves a prosthetic valve.

Other complications include cerebrovascular or peripheral vascular ischemia, thrombosis, and renal failure.

What causes it

In acute infective endocarditis, infecting organisms include:

• group A nonhemolytic Streptococcus (rheumatic endocarditis)

• pneumococcus

• Staphylococcus

• Enterococcus

• gonococcus (rare).

Causes of acute endocarditis in IV drug users include Staphylococcus aureus, Pseudomonas bacteria, Candida fungi, and skin saprophytes that are typically harmless.

In subacute infective endocarditis, infecting organisms include:

• Streptococcus viridans, which normally inhabits the upper respiratory tract

• Streptococcus faecalis (enterococcus), usually found in GI and perineal flora.

How it happens

In endocarditis, fibrin and platelets cluster on valve tissue and engulf circulating bacteria or fungi. This process produces vegetation, which in turn may cover the valve surfaces, causing deformities and destruction of valvular tissue. The destruction may then extend to the chordae tendineae (threadlike bands of fibrous tissue that attach the tricuspid and mitral valves to the papillary muscles), causing them to rupture. This rupturing then leads to valvular insufficiency. Vegetative growth on the heart valves, the endocardial lining of a heart chamber, or the endothelium of a blood vessel may embolize to the spleen, kidneys, CNS, extremities, and lungs.

What to look for

Early clinical features of endocarditis are usually nonspecific and include:

• weakness and fatigue

• weight loss

• anorexia

• arthralgia

• night sweats

• intermittent fever (may recur for weeks).

A loud, regurgitant murmur may also be present. This murmur is typical of the underlying rheumatic or congenital heart disease.

A sudden change in an existing murmur or the discovery of a new murmur along with fever is a classic sign of endocarditis.

A sudden change in an existing murmur or the discovery of a new murmur along with fever is a classic sign of endocarditis.

|

What else?

Other signs include:

• petechiae on the skin (especially common on the upper anterior trunk); the buccal, pharyngeal, or conjunctival mucosa; and the nails (splinter hemorrhages)

• Osler’s nodes (small, raised, swollen tender areas that most commonly occur on the hands and feet)

• Roth’s spots (round, white retina spots surrounded by hemorrhage)

• Janeway lesions (irregular, painless, erythematous lesions on the soles of the feet, the palms, and the fingers)

• persistent cough

• edema—swelling of feet and hands.

Subacute signs

In subacute endocarditis, embolization from vegetating lesions or diseased valve tissue may produce:

• splenic infarction (abdominal rigidity and pain in the left upper quadrant that radiates to the left shoulder)

• renal infarction (hematuria, pyuria, flank pain, and decreased urine output and renal function)

• cerebral infarction (hemiparesis, aphasia, or other neurologic deficits)

• pulmonary infarction (cough, pleuritic pain, pleural friction rub, dyspnea, and hemoptysis; most common in right-sided endocarditis, which commonly occurs among IV drug abusers and after cardiac surgery)

• peripheral vascular occlusion (severe pain, limb pallor and coldness, absent pulse, diminished sensation, and paralysis, a late sign of impending peripheral gangrene).

What tests tell you

• Three or more blood cultures drawn at least 1 hour apart during a 24-hour period identify the causative organism in up to 90% of patients. The remaining 10% may have negative blood cultures, possibly suggesting fungal infection.

• Echocardiography, including transesophageal echocardiography (TEE), may identify vegetations and valvular damage.

• Electrocardiogram (ECG) readings may show atrial fibrillation and other arrhythmias that accompany valvular disease.

• Abnormal laboratory results include elevated white blood cell (WBC) count; abnormal histiocytes (macrophages); elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR); normocytic, normochromic

anemia (in subacute bacterial endocarditis); and rheumatoid factor (occurs in about 50% of patients).

anemia (in subacute bacterial endocarditis); and rheumatoid factor (occurs in about 50% of patients).

|

How it’s treated

Treatment seeks to eradicate the infecting organism. It should start promptly and continue over several weeks. The doctor bases antibiotic selection on sensitivity studies of the infecting organism —or the probable organism, if blood cultures are negative. IV antibiotic therapy usually lasts 4 to 6 weeks and may be followed by oral antibiotics.

Be supportive

Supportive treatment includes bed rest, antipyretics for fever and aches, and sufficient fluid intake. Severe valvular damage, especially aortic insufficiency, or infection of a cardiac prosthesis may require corrective surgery if refractory heart failure develops.

What to do

• Collaborate with a skilled team, which may include a cardiologist, an infectious disease specialist, a cardiothoracic surgeon, a nephrologist, and a cardiac and stroke rehabilitation team.

• Obtain the patient’s allergy history.

• Administer antibiotics on time to maintain consistent blood levels. Check dilutions for compatibility with other patient medications, and use a compatible solution (e.g., add methicillin to a buffered solution).

Check progress

• Evaluate the patient. The patient has recovered from endocarditis if he maintains a normal temperature, clear lungs, stable vital signs, and adequate tissue perfusion and can tolerate activity for a reasonable period and maintain normal weight.

• Teach the patient about the anti-infective medication that he’ll continue to take. Stress the importance of taking the medication and restricting activity for as long as recommended.

• Tell the patient to watch for and report signs of embolization and to watch closely for fever, anorexia, and other signs of relapse that could occur about 2 weeks after treatment stops.

Stay the course

• Discuss the importance of completing the full course of antibiotics, even if he’s feeling better. Make sure a susceptible patient understands the need for prophylactic antibiotics before, during, and after dental work, childbirth, and genitourinary, GI, or gynecologic procedures.

• Document vital signs, cardiac and respiratory status, and response to treatment.

|

Myocarditis

Myocarditis is a focal or diffuse inflammation of the cardiac muscle (myocardium). It may be acute or chronic and can strike at any age.

|

Vague signs, sudden recovery

In many cases, myocarditis fails to produce specific cardiovascular symptoms or ECG abnormalities. The patient commonly experiences spontaneous recovery without residual defects.

And to complicate matters…

Occasionally, myocarditis is complicated by heart failure and, rarely, it leads to cardiomyopathy. Other complications include arrhythmias, pulmonary edema, respiratory distress, and multipleorgan-dysfunction syndrome (MODS).

What causes it

Potential causes of myocarditis include:

• viral infections (most common cause in the United States), such as coxsackievirus A and B strains and, possibly, poliomyelitis, influenza, rubeola, rubella, adenoviruses, echoviruses, HIV, and mononucleosis

• bacterial infections, such as diphtheria; tuberculosis; typhoid fever; tetanus; staphylococcal, pneumococcal, and gonococcal infections; and tick-borne bacteria responsible for Lyme disease

• hypersensitivity reactions, such as acute rheumatic fever and postcardiotomy syndrome

• radiation therapy to the chest

• chronic alcoholism

• parasitic infections, such as toxoplasmosis and, especially, South American trypanosomiasis (Chagas’ disease) in infants and immunosuppressed adults

• intestinal parasitic infections such as trichinosis

• yeast (Candida), molds (Aspergillus), and other fungi.

How it happens

The myocardium may become damaged when an infectious organism triggers an autoimmune, cellular, or humoral reaction or when a noninfectious cause leads to toxic inflammation. In either case, the resulting inflammation may lead to hypertrophy, fibrosis, and inflammatory changes of the myocardium and conduction system.

Feeling the flab

Because of this damage, the heart muscle weakens and contractility is reduced. The heart muscle becomes flabby and dilated, and pinpoint hemorrhages may develop.

What to look for

Signs and symptoms of myocarditis include:

• dyspnea and fatigue

• palpitations and fever

• mild, continuous pressure or soreness in the chest

• signs and symptoms of heart failure (with advanced disease)

• other signs and symptoms of viral infections such as headache, body ache, joint pain, sore throat, and diarrhea.

What tests tell you

• Laboratory tests may reveal elevated cardiac enzymes, such as creatine kinase (CK) and CK-MB, increased WBC count and ESR, and elevated antibody titers (e.g., antistreptolysin-O titer; which indicates a recent streptococcal infection in rheumatic fever).

• ECG changes provide the most reliable diagnostic information. Typically, the ECG shows diffuse ST-segment and T-wave abnormalities such as occur with pericarditis, conduction defects (prolonged PR interval), and other supraventricular ectopic arrhythmias.

• Chest X-ray to assess size and shape of heart and to see fluid accumulation in lungs due to heart failure.

• Echocardiogram to assess heart function.

• Stool and throat cultures may allow identification of bacteria.

• Endomyocardial biopsy provides a definitive diagnosis.

How it’s treated

Treatment for myocarditis includes antibiotics for bacterial infection, modified bed rest to decrease heart workload, and careful management of complications. If a thromboembolism occurs, anticoagulant therapy is required. If heart failure occurs, inotropic drugs, such as amrinone, dobutamine, or dopamine, may be necessary. Nitroprusside (Nitropress) and nitroglycerin may be administered to reduce preload and afterload.

Upping the ante

Treatment with immunosuppressive drugs or steroids is controversial but may be helpful after the acute inflammation has passed. Patients with low cardiac output may benefit from intra-aortic balloon pulsation and ventricular assist devices. Heart transplantation is performed as a last resort.

What to do

• Collaborate with a skilled team, which may include a cardiologist, an infectious disease specialist, a cardiothoracic surgeon, a nephrologist, and a cardiac and stroke rehabilitation team.

|

• Assess cardiovascular status frequently, watching for such signs of heart failure as dyspnea, hypotension, and tachycardia.

• Assist the patient with activities such as bathing as necessary. Encourage use of a bedside commode because this activity stresses the heart less than using a bedpan.

• Evaluate the patient. After successful treatment, the patient’s cardiac output should be adequate, as evidenced by normal blood pressure; warm, dry skin; normal level of consciousness; and absence of dizziness. He should be able to tolerate a normal level of activity, his temperature should be normal, and he shouldn’t be dyspneic. Tests such as echocardiography help confirm myocardial recovery.

• Teach the patient about anti-infective drugs. Stress the importance of taking the prescribed drug as ordered.

It’s only for a while

• Reassure the patient that activity limitations are temporary. Offer diversional activities that are physically undemanding.

• Stress the importance of bed rest. During recovery, recommend that the patient resume normal activities slowly and avoid intense exercise and competitive sports.

• Document vital signs, cardiac and respiratory status, and response to treatment. Document all patient teaching and the patient’s understanding of the information.

|

Pericarditis

Pericarditis is an inflammation of the pericardium, the fibroserous sac that envelops, supports, and protects the heart. It occurs in acute and chronic forms:

• Acute pericarditis can be fibrinous or effusive, with purulent, serous, or hemorrhagic exudate.

• Chronic constrictive pericarditis is characterized by dense fibrous pericardial thickening.

Complications of pericarditis include pericardial effusion, heart failure, cardiac tamponade, respiratory distress, and MODS.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree