Infections of the Myocardium

Fabio R. Tavora, M.D., Ph.D.

Allen P. Burke, M.D.

Viral and Postviral Myocarditis

Coxsackievirus type B is a type of enterovirus that causes a flu-like systemic illness that frequently involves the heart. Coxsackievirus type B is associated with epidemic disease and is frequently symptomatic; it is relatively uncommon, however, in prospective series of acute myocarditis that include subclinical cases.1,2 It usually occurs in infants and children, in whom systemic disease is frequent. The mean age at presentation in symptomatic patients requiring hospitalization is a little under 3 years. Extracardiac symptoms include herpangina in threefourths of patients

and meningitis in about one-fourth. Most children survive, and type CB3 is associated with a worse prognosis.3 In adults, coxsackieviral myocarditis is rare, especially with associated systemic disease.4,5

and meningitis in about one-fourth. Most children survive, and type CB3 is associated with a worse prognosis.3 In adults, coxsackieviral myocarditis is rare, especially with associated systemic disease.4,5

Adenovirus is the most frequent viral etiology in subclinical myocarditis as well as tissue diagnosis based on polymerase chain reaction; both receptors for adeno- and enterovirus have been demonstrated in human myocytes.6 A recent autopsy study, however, found no case of adenoviral DNA in cardiac tissue with myocarditis.7 The difficulty in detecting viral organisms and establishing causation is in part because the virus is largely cleared before significant inflammation or symptoms develop. The use of the term “postviral” myocarditis reflects this phenomenon.8

Other viruses that have been associated with myocarditis include parvovirus, influenza, poliomyelitis, Epstein-Barr virus, HIV-1, viral hepatitis, mumps, rubeola, varicella, variola/vaccinia, arbovirus, respiratory syncytial virus, herpes simplex virus, yellow fever virus, parvovirus, and rabies.9,10 In endemic areas, high rates of dengue fever myocarditis with sudden death cases have been reported.11,12 A specific etiologic relationship has not always been proven, however. For example, in the case of parvovirus, which is implicated in dilated cardiomyopathy, 13 there is a high rate of detection of viral-specific DNA in control tissue.7

The histologic features of inflammation are not specific for any virus, and a lymphocytic myocarditis is typically described in reports of unusual viral etiologies, with some exceptions. See Chapter 21 for detailed histologic description of lymphocytic myocarditis.

Bacterial Myocarditis

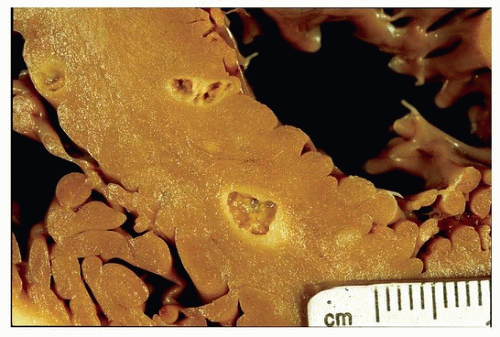

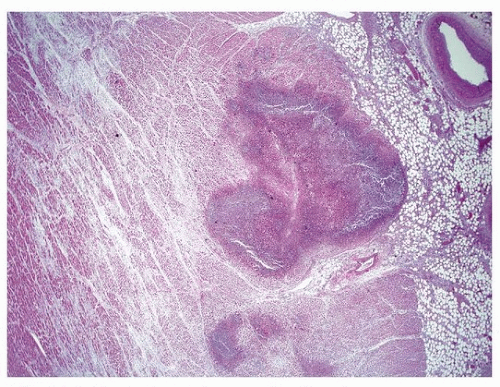

Acute neutrophilic myocarditis is rare and may be seen as an early phase in viral infections or as a result of bacterial myocarditis, often complicating endocarditis, in which case microabscesses are common (Figs. 166.1, 166.2, 166.3, 166.4).

In immunocompetent patients, bacterial myocarditis in the absence of valvular endocarditis is unusual but may occur concomitantly with extensive bacterial pneumonia, caused especially by mycoplasma16,17,18 or chlamydia.19 Diagnosis is only rarely confirmed by endomyocardial biopsy, which shows lymphocytic infiltrates with myocyte necrosis.20 In addition to microbiologic studies, clinical and laboratory studies consistent with myocarditis (ECG, serology for troponins, elevations of acute phase reactants, exclusion of coronary and other cardiac disease), myocarditis can also be suggested by cardiac magnetic resonance imaging.19

FIGURE 166.1 ▲ Bacterial myocarditis with abscesses. These are seen in the ventricular septum in this case. |

FIGURE 166.2 ▲ Bacterial myocarditis. Microabscesses are common, with necrosis and purulent exudate. |

Disseminated leptospirosis, when fatal, involves the heart in over onethird of cases.21 Histologic findings include hemorrhage and lymphocytic infiltrates. The organisms can be identified by immunohistochemical methods or silver stains and are most numerous in the kidneys.21

Other infections that may result in myocarditis include legionella, leptospirosis,22 syphilis,23 and tuberculosis. The latter presents typically as pericardial disease,24 but nodular and miliary cardiac lesions can occur.25 A variety of bacteria have been implicated in myocarditis in immunosuppressed patients. Histologically, the infection is similar to bacterial infections elsewhere and is characterized by neutrophilic infiltrates and microabscess formation. Focal tissue necrosis and myocyte loss are invariably seen. In sepsis, the myocardium can be secondarily involved and show intravascular inflammatory cells extending to the interstitium (Fig. 166.5).

Lyme disease (infection with Borrelia burgdorferi) results in cardiac symptoms in about 5% of patients, especially in the early stage of disseminated disease. Symptoms include conduction disturbances (especially heart block), pericarditis, and heart failure. There have been only a handful of reports with histologic confirmation of myocarditis, which shows intense interstitial inflammation with myocyte necrosis and mixed chronic inflammatory infiltrate (Figs. 166.6 and 166.7).26 Cardiac magnetic resonance may demonstrate nonspecific changes of myocarditis.27

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree