Genetic susceptibility is important in 3–6%

Risk factors include poverty, overcrowding and poor hygiene

Clinical features

Multisystemic disorder. Joint involvement is most common, followed by carditis.

Investigations

Blood tests and culture, ECG, chest X-ray, antistreptolysin O testing, echocardiography

Management

Bed rest, antimicrobial therapy and inflammatory suppression

Management of heart failure and chorea

Secondary prophylaxis (IM benzylpenicillin three-weekly)

Historically, rheumatic heart disease was one of the most common causes of valvular disease. With the advent of penicillin in modern society, the incidence of this condition in the developed world has declined sharply. However, it remains useful to be aware of its continuing impact globally. Worldwide, acute rheumatic fever is the leading cause of cardiovascular death in the young. This chapter will focus on acute rheumatic fever, the precedent responsible for this debilitating cardiac condition.

6.2.1 Definition

Acute rheumatic fever is a multisystem disorder that occurs as a result of an autoimmune-mediated reaction to Group A streptococcal (GAS) infection.

6.2.2 Epidemiology

- Common in children aged 5 to 14 years; rare in those over age 30

- High incidence in developing countries, especially where there is overcrowding and poor access to healthcare

- Low incidence in developed countries. This is due to the use of antibiotics for bacterial pharyngitis, better hygiene, and a decline in rheumatogenic strains of Streptococcus.

- Globally, it is estimated that over 25 million people are affected by rheumatic heart disease, contributing to approximately 345 000 deaths per year.

6.2.3 Aetiology

The key risk factor is infection with GAS:

- Rheumatogenic strains: although specific strains of GAS are associated with acute rheumatic fever, any streptococcal infection that can cause a pharyngitis can lead to rheumatic fever. Additionally, pharyngitic infection appears to be a prerequisite, as studies show that GAS skin infections rarely lead to acute rheumatic fever.

- Genetic susceptibility: acute rheumatic fever has high heritability in some families, with 3–6% thought to have some form of genetic susceptibility – especially those who express particular HLA antigens.

// Why? //

Expressing specific HLA antigens (particularly D8/17) appears to trigger cross-reaction with host antibodies originally produced against GAS

- Associated factors: spreading of GAS infection occurs with poverty and overcrowded living.

6.2.4 Pathophysiology

- The pathogenesis of acute rheumatic fever is not completely understood

- Typically presents 2–3 weeks after an episode of streptococcal pharyngitis

- A delayed immune-mediated response where antibodies are produced against GAS antigens

- Rheumatic inflammation in the heart can affect the:

- Pericardium (often asymptomatic)

- Myocardium (rarely causes heart failure)

- Endocardium (i.e. valvular tissue – most common and important).

- Pericardium (often asymptomatic)

// Why? //

During an infection, monoclonal antibodies are formed against GAS antigens – mainly M-protein and N-acetyl glucosamine. Due to molecular mimicry between antigens and human host tissue, these antibodies can then cross-react with cardiac proteins as well as proteins in synovial, neuronal, subcutaneous and dermal tissues. This hypersensitivity reaction results in inflammation and gives rise to the clinical features of acute rheumatic disease.

6.2.5 Clinical features

The diagnosis for acute rheumatic fever is aided using the revised Jones Criteria:

- Two major criteria or one major and two minor, plus

- Evidence of a preceding streptococcal infection

- positive throat culture

- positive rapid streptococcal antigen/rising streptococcal antibody titre (anti-streptolysin O or anti-deoxyribonuclease B)

- recent scarlet fever.

- positive throat culture

EXAM | The mnemonics ACES2 (for major criteria) and FRAPP (for minor criteria) are useful for remembering the Jones criteria. |

Major criteria

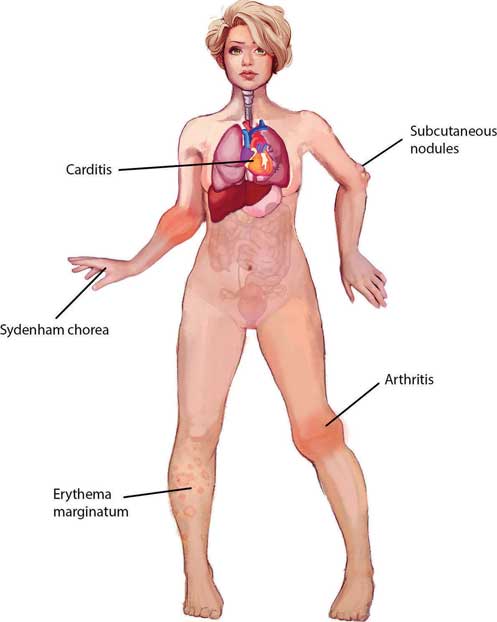

Arthritis (75% of patients)

- Acute, migratory polyarthritis

- Joints are red, swollen and tender

- Lasts between one day and four weeks

- Typically affects large joints (knees, ankles, elbows, wrists)

Carditis (40% of patients)

- Breathlessness, palpitations, chest pain, syncope

- Murmurs

- mitral regurgitation (most common)

- aortic regurgitation

- mitral regurgitation (most common)

- Carey Coombs murmur

- Pericardial rub

Erythema marginatum (5–15% of patients)

- Mainly on trunk and proximal extremities

- Rash with red, raised edges and a clear centre

Subcutaneous nodules (10% of patients)

- Small, firm, painless nodules on extensor surfaces of bones and tendons

- Usually appear more than three weeks after the onset of other manifestations

Sydenham’s chorea (St Vitus’ dance) (10–30% of patients)

- Late manifestation (at least three months after acute episode)

- Emotional lability followed by involuntary, semi-purposeful movements of hands, feet or face

- Explosive or halting speech

// Why? //

A Carey Coombs murmur is characteristically a soft, rumbling, mid-diastolic murmur. It is caused by pseudo-mitral stenosis as the regurgitant volume of blood increases flow over the mitral valve during diastolic filling of the left ventricle. This is due to vegetations on the valve.

Minor criteria

First-degree AV block – prolonged PR interval (not if carditis is one of the major criteria)

Raised acute phase reactants – ESR/CRP/leucocytosis

Arthralgia (not if arthritis is one of the major criteria)

Pyrexia

Previous rheumatic fever

Figure 6.1 – Jones major criteria.

6.2.6 Differential diagnoses

The differential diagnosis is wide due to the multisystem nature of the condition:

- Infective endocarditis

- most important differential for the carditis of acute rheumatic fever

- systemically unwell with positive blood cultures

- most important differential for the carditis of acute rheumatic fever

- Septic arthritis must be excluded in any arthropathy

- joints typically warm and tender with systemic upset

- usually a monoarthropathy

- suspected infected joints should be aspirated for culture. Inflammatory markers are raised

- joints typically warm and tender with systemic upset

- Transient synovitis

- a diagnosis of exclusion

- most common cause of hip pain in a young child, and often follows a viral upper respiratory tract infection or gastroenteritis

- a diagnosis of exclusion

- Juvenile idiopathic arthritis

- typically longer history than acute rheumatic fever with no preceding pharyngitis

- other systemic features such as conjunctivitis may be present. Positive for ANA antibodies

- typically longer history than acute rheumatic fever with no preceding pharyngitis

- Chorea

- encephalitis: unusual behaviour, pyrexia and convulsions

- drug-induced: dopamine antagonists in young women (e.g. metoclopramide)

- Wilson’s disease: liver disease and neuropsychiatric symptoms are prominent.

- Huntington’s disease

- encephalitis: unusual behaviour, pyrexia and convulsions

6.2.7 Investigations

First-line

To establish presence of streptococcal infection and carditis as well as to exclude infective endocarditis:

- Throat swab culture – often negative

- Anti-streptococcal serology – antistreptolysin O (ASO) or anti-DNAse B (most specific test)

- ECG – AV block, features of pericarditis

- Chest X-ray

- Blood tests – raised WCC and acute phase reactants (ESR/CRP)

- Blood cultures – to exclude infective endocarditis

- Echocardiography – WHO recommends this in all suspected carditis; it may reveal valvular involvement.

EXAM | Anti-streptococcal serology is the most important means of demonstrating antecedent infection. |

Second-line

To exclude other differential diagnoses:

- Systemic auto-antibodies in systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE)

- Copper and caeruloplasmin for Wilson’s disease.

6.2.8 Management

GUIDELINES: Management of rheumatic fever (WHO, 2004)

The WHO advocates the following five-principle approach:

1. General measures

• Bed-chair rest reduces joint pain and cardiac workload

• Continue until temperature, CRP/ESR and leucocyte counts normalise

2. Antimicrobial therapy

• Single dose benzylpenicillin IM or oral penicillin V for 10 days

3. Suppression of inflammatory response

• Mostly for symptomatic relief of arthropathy; there is no evidence that it alters the course of carditis or reduces subsequent incidence of heart failure

• Aspirin is first-line

• Corticosteroids if no response to salicylates, pericarditis or heart failure

• No evidence that corticosteroids are any better than aspirin

4. Management of heart failure

• Mainstay is bed rest and corticosteroids (note that steroids can worsen heart failure)

• If severe, may require ACE inhibitor, digoxin and diuretics

5. Management of chorea

• Chorea is usually self-limiting, but protracted courses can cause disability so should be treated

• First-line is a benzodiazepine (e.g. diazepam).

// PRO-TIP //

The arthritis of rheumatic fever typically responds to aspirin – if not, consider another diagnosis.

6.2.9 Secondary prophylaxis

Long-term secondary prophylaxis is required to prevent chronic recurrence of acute rheumatic fever and the onset of rheumatic heart disease. The duration of therapy varies, with different figures quoted by the American Heart Association (AHA) and the World Health Organization (WHO).

- IM benzylpenicillin every three to four weeks is the most effective strategy

- Oral penicillin daily is an alternative, but non-compliance is an issue

- Duration of therapy (based on WHO guidelines):

- No carditis or valvular disease: five years, or until 18 years of age (whichever is longest)

- With carditis but no persistent valvular disease: ten years, or until 25 years of age (whichever is longer)

- With carditis and persistent valvular disease: until 40 years of age or lifelong.

- No carditis or valvular disease: five years, or until 18 years of age (whichever is longest)

6.2.10 Prognosis

- At least 50% of those with carditis will go on to develop chronic rheumatic heart disease

- Recurrences can be precipitated by further streptococcal infections, pregnancy or the use of the combined oral contraceptive pill.

6.3 Infective endocarditis (IE)

The heart, like every other organ in the body, is susceptible to infection. Infective endocarditis (IE) is a condition that has both cardiac and systemic manifestations. It can easily be missed by clinicians and so it is crucial for one to be well-versed with the aetiology, presentation and management of this disease.

Infective endocarditis In A Heartbeat

Epidemiology | More common in males; associated with increasing age |

Aetiology | S. aureus is the most common cause overall; Strep. viridans is the most common cause of subacute IE |

Clinical features | New or worsening cardiac murmur |

Investigations | Blood tests (FBC, ESR/CRP), blood cultures with meticulous aseptic technique, ECG, CXR, echocardiography |

Management | IV antibiotics for 4–6 weeks empirically with combinations of ceftriaxone, vancomycin and gentamicin |

6.3.1 Definition

Infective endocarditis refers to the infection of the endocardium and all of its related structures, including the cardiac valves and chordae tendineae. It can be acute, subacute or chronic.

6.3.2 Epidemiology

- The incidence of IE is 1.7–6.2 cases per 100 000 patients

- Males are predominantly affected, with M:F ratios varying from 3:2 to 9:1

- In the developed world, IE is mostly a disease seen in elderly patients and commonly a consequence of rheumatic heart disease

- Its incidence is stable, although some argue is increasing. This reflects the increasing prevalence of prosthetic valves, medically invasive interventions and intravenous drug users (IVDUs).

6.3.3 Aetiology

The majority of cases of endocarditis occur as a result of infection. However, there are some important non-infective causes to be aware of.

Infective

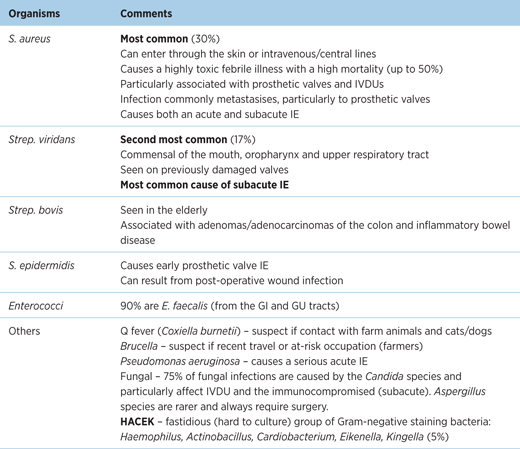

Table 6.1 – Organisms causing infective endocarditis

Non-infective

- Physical trauma caused by intravenous catheters or pacing wires

- Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE)

- Marantic (thrombotic non-bacterial) endocarditis

- Metastatic lung, gastrointestinal and pancreatic cancers

- Chronic infections, e.g. tuberculosis, osteomyelitis

// PRO-TIP //

Libman–Sacks lesions are non-bacterial valvular vegetations found in SLE patients, correlating with duration, severity of the disease and anticardiolipin antibody concentrations. The vegetations are typically found in the left side of the heart, most often on the mitral valve. (SLE causes LSE)

6.3.4 Risk factors

Several risk factors have been found to be associated with infective endocarditis:

- Age – infective endocarditis is seen mostly in the elderly due to accumulation of other risk factors

- Male gender

- Poor dental hygiene and dental procedures – aberrant oral flora is likely to predispose to infective endocarditis. Dental procedures provide a direct portal of entry, but antibiotic prophylaxis is controversial.

- Intravenous drug use provides a portal of entry for potentially harmful skin flora and other organisms. The injected drug may also predispose to endothelial damage in the heart. The right side of the heart is commonly affected (particularly the tricuspid valve) due to blood flow. However, left-sided IE is still more common in IVDU.

- Structural heart disease – 75% of IE patients have underlying structural heart disease

- valvular disease – this includes rheumatic heart disease

- prosthetic heart valves – risk of IE is 1 in 4 in the first year of prosthetic valve replacement and 1% per year thereafter

- chronic haemodialysis – multifactorial (immunodeficiency, intravascular access)

- valvular disease – this includes rheumatic heart disease

- HIV.

6.3.5 Pathophysiology

There are two main disease processes underpinning infective endocarditis:

1. Endocardial injury

- Due to turbulent blood flow across the valve

- Refer to ‘risk factors’ for potential causes for this turbulence

2. Bacteraemia

- Spontaneous bacteraemia from extra-cardiac sources, most commonly the gingiva. Other sources include the skin, gastrointestinal and genitourinary tracts.

- Bacteraemia can occur during any invasive intravascular procedure.

Injury to the endocardium as a result of turbulent blood flow exposes underlying collagen, which serves as a surface for aggregation of platelets and fibrin adhesion. The thrombus formed is initially sterile and is known as a non-bacterial vegetation. Bacterial invasion of the vegetation subsequently occurs as a consequence of microbial surface component recognising adhesive molecules (MSCRAMM). The resultant infected vegetative thrombus further enlarges secondary to aggregation of platelets and fibrin, and is relatively immune from host defences.

// Why? //

Left-sided IE is more common because the velocity of blood flow on the left side is far greater, causing more turbulence with increased subsequent risk of endocardial injury.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree