Infection and inflammation

Infectious and inflammatory disorders of the respiratory tract include bronchiectasis, croup, epiglottiditis, pharyngitis, pleural effusion and empyema, pleurisy, pneumonia, severe acute respiratory syndrome, sinusitis, tonsillitis, and tuberculosis.

BRONCHIECTASIS

Bronchiectasis is characterized by chronic abnormal dilation of the bronchi and destruction of the bronchial walls. It can occur throughout the tracheobronchial tree or be confined to one segment or lobe. It’s usually bilateral and involves the basilar segments of the lower lobes.

The disease has three forms: cylindrical (fusiform), varicose, and saccular (cystic). It affects people of both sexes and all ages. With antibiotics available to treat acute respiratory tract infections, the incidence of bronchiectasis has dramatically decreased during the past 20 years. Its incidence is highest among Inuit populations in the Northern Hemisphere and the Maoris of New Zealand. Bronchiectasis is irreversible. (See Forms of bronchiectasis, page 176.)

Pathophysiology

Bronchiectasis results from conditions associated with repeated damage to bronchial walls and with abnormal mucociliary clearance, which causes a breakdown of supporting tissue adjacent to the airways. Such conditions include:

complications of measles, pneumonia, pertussis, or influenza

congenital anomalies (rare), such as bronchomalacia, congenital bronchiectasis, and Kartagener’s syndrome (bronchiectasis, sinusitis, and dextrocardia), and various rare disorders such as immotile cilia syndrome

immune disorders (agammaglobulinemia, for example)

inhalation of corrosive gas or repeated aspiration of gastric juices

cystic fibrosis

obstruction (by a foreign body, tumor, or stenosis) with recurrent infection

recurrent, inadequately treated bacterial respiratory tract infections such as tuberculosis.

FORMS OF BRONCHIECTASIS

The different forms of bronchiectasis may occur separately or simultaneously:

In cylindrical bronchiectasis, the bronchi expand unevenly, with little change in diameter, and end suddenly in a squared-off fashion.

In varicose bronchiectasis, abnormal, irregular dilation and narrowing of the bronchi give the appearance of varicose veins.

In saccular bronchiectasis, many large dilations end in sacs. These sacs balloon into pus-filled cavities as they approach the periphery and are then called saccules.

In bronchiectasis, hyperplastic squamous epithelia denuded of cilia replace ulcerated columnar epithelia. Abscess formation occurs, involving all layers of the bronchial walls. This produces inflammatory cells and fibrous tissues. The result is both dilation and narrowing of the airways. Sputum stagnates in the dilated bronchi and leads to secondary infection, characterized by inflammation and leukocytic accumulations. Additional debris collects in and occludes the bronchi. Building pressure from the retained secretions induces mucosal injury. Extensive vascular proliferation of bronchial circulation occurs and produces frequent hemoptysis.

Assessment findings

The patient may complain of frequent bouts of pneumonia; a history of coughing up blood or blood-tinged sputum; a chronic cough that produces copious, foul-smelling, mucopurulent secretions (up to several cups daily); dyspnea; weight loss; and malaise.

Inspection of the patient’s sputum may show a cloudy top layer, a central layer of clear saliva, and a heavy, thick, purulent bottom layer.

In advanced disease, the patient may have clubbed fingers and toes and cyanotic nail beds.

If the patient also has a complicating condition, such as pneumonia or atelectasis, percussion may detect dullness over lung fields.

Auscultation may reveal coarse crackles during inspiration over involved lobes or segments and, occasionally, wheezes.

With complicating atelectasis or pneumonia, you may hear diminished breath sounds during auscultation.

Diagnostic test results

Bronchography identifies the location and extent of disease.

Bronchoscopy helps to identify the source of secretions or the bleeding site in hemoptysis.

Chest X-rays show peribronchial thickening, atelectatic areas, and scattered cystic changes that suggest bronchiectasis.

Complete blood count can reveal anemia and leukocytosis.

Computed tomography scan reveals anatomic changes.

Pulmonary function tests detect decreased vital capacity, expiratory flow, and hypoxemia; these tests also help evaluate disease severity, therapeutic effectiveness, and the patient’s suitability for surgery.

Sputum culture and Gram stain identify predominant pathogens.

Sweat electrolyte tests may reveal cystic fibrosis.

Treatment

Antibiotic therapy (oral or I.V.) for 7 to 10 days—or until sputum production decreases—is the principal treatment. Bronchodilators and postural drainage and chest percussion help remove secretions if the patient has bronchospasm and thick, tenacious sputum. Occasionally, bronchoscopy may be used to remove secretions. Oxygen therapy may be used for hypoxia. Segmental resection, bronchial artery embolization, or lobectomy may be necessary if pulmonary function is poor.

The only cure for bronchiectasis is surgical removal of the affected lung portion. However, the patient with bronchiectasis affecting both lungs probably won’t benefit from surgery.

Nursing interventions

Provide supportive care, and help the patient adjust to the lifestyle changes that irreversible lung damage causes.

Give antibiotics, as ordered, and record the patient’s response.

Give oxygen, as needed, and assess gas exchange by monitoring arterial blood gas values, as ordered.

Perform chest physiotherapy, including postural drainage and chest percussion for involved lobes, several times per day, especially in the early morning and before bedtime.

Provide a warm, quiet, comfortable environment. Also, help the patient to alternate rest and activity periods.

Provide well-balanced, high-calorie meals for the patient. Offer small, frequent meals to prevent fatigue.

Make sure the patient receives adequate hydration to help thin secretions and promote easier removal.

Give frequent mouth care to remove foul-smelling sputum. Provide the patient with tissues and a waxed bag for disposal of the contaminated tissues.

Watch for developing complications, such as right-sided heart failure and cor pulmonale.

After surgery, give meticulous postoperative care. Monitor vital signs, encourage deep breathing and position changes every 2 hours, and provide chest tube care. (See Bronchiectasis teaching topics.)

DISCHARGE TEACHING

Show family members how to perform postural drainage and percussion. Also, teach the patient coughing and deep-breathing exercises to promote good ventilation and assist in secretion removal. Instruct him to maintain each postural drainage position for 10 minutes. Then direct the caregiver in performing percussion and instructing the patient to cough.

Advise the patient to stop smoking because it stimulates secretions and irritates the airways. Refer the patient to a local smoking-cessation group.

Instruct the patient to avoid air pollutants and people with known upper respiratory tract infections.

Direct the patient to take medications (especially antibiotics) exactly as ordered. Make sure he knows the adverse effects associated with his medications. Instruct him to notify the physician if any of these effects occur.

Teach the patient to dispose of all secretions properly to avoid spreading the infection to others. Advise him to wash his hands thoroughly after disposing of contaminated tissues.

Urge the patient to keep up-to-date in his immunization schedule to prevent childhood diseases.

Encourage the patient to rest as much as possible.

Discuss dietary measures. Encourage the patient to follow a balanced, high-protein diet. Suggest that he eat small, frequent meals. Explain that milk products may increase the viscosity of secretions.

Encourage the patient to drink plenty of fluids to thin secretions and aid expectoration.

If the patient needs surgery, offer complete preoperative and postoperative instructions. Forewarn him if he is to have an I.V. line and chest tubes. Explain the reason for these procedures.

Tell the patient to seek prompt attention for respiratory infections.

Tell the patient to avoid air pollutants and people with upper respiratory tract infections. Instruct him to take medications (especially antibiotics) exactly as prescribed.

CROUP

Croup is a severe inflammation and obstruction of the upper airway. This childhood disease affects boys more than girls. The barking cough of croup results from soft tissue collapsing in the airway and then being forced open. Older children develop rings of cartilage that prevent the collapse.

Croup usually occurs in the winter as acute laryngotracheobronchitis (the most common form), laryngitis, or acute spasmodic laryngitis. It must be distinguished from epiglottiditis.

Usually mild and self-limiting, acute laryngotracheobronchitis appears mostly in children ages 3 months to 3 years. Acute spasmodic laryngitis affects children ages 1 to 3, particularly those with allergies and a family history of croup. Overall, up to 15% of patients have a family history of croup. Recovery is usually complete.

Usually mild and self-limiting, acute laryngotracheobronchitis appears mostly in children ages 3 months to 3 years. Acute spasmodic laryngitis affects children ages 1 to 3, particularly those with allergies and a family history of croup. Overall, up to 15% of patients have a family history of croup. Recovery is usually complete.

Pathophysiology

Croup usually results from a viral infection. Parainfluenza viruses cause about two-thirds of such infections; adenoviruses, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), influenza viruses, measles viruses, and bacteria (pertussis and diphtheria) account for the rest.

Complications

Airway obstruction

Dehydration

Ear infection

Pneumonia

Respiratory failure

Assessment findings

Typically, the child or his parents report a recent upper respiratory tract infection preceding croup.

On inspection, you may observe the use of accessory muscles with nasal flaring during breathing.

You typically hear the child’s sharp, barklike cough and hoarse or muffled vocal sounds.

As croup progresses, the patient may display further upper airway obstruction with severely compromised ventilation. (See How croup affects the upper airway.)

Auscultation may disclose inspiratory stridor and diminished breath sounds. These signs and symptoms may last for only a few hours, or they may persist for 1 to 2 days.

LARYNGOTRACHEOBRONCHITIS

The patient may complain of fever and breathing problems that occur more often at night. Typically, the child becomes frightened because he can’t exhale (because inflammation causes edema in the bronchi and bronchioles).

During auscultation, you may hear diffusely decreased breath sounds, expiratory rhonchi, and scattered crackles.

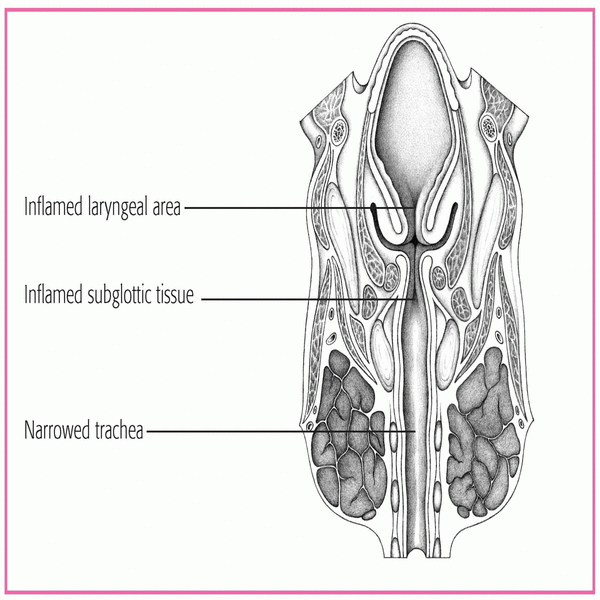

UP CLOSE

In croup, inflammatory swelling and spasms constrict the larynx, thereby reducing airflow. This cross-sectional drawing (from chin to chest) shows the upper airway changes caused by croup. Inflammatory changes almost completely obstruct the larynx (which includes the epiglottis) and significantly narrow the trachea.

|

LARYNGITIS

The patient usually reports mild signs and symptoms and no respiratory distress. If the patient is an infant, however, some respiratory distress may occur.

In children, the history may include such signs and symptoms as a sore throat and cough that, rarely, may progress to marked hoarseness.

Inspection may disclose suprasternal and intercostal retractions, inspiratory stridor, dyspnea, diminished breath sounds, restlessness and, in later stages, severe dyspnea and exhaustion.

ACUTE SPASMODIC LARYNGITIS

The patient history may reveal mild to moderate hoarseness and nasal discharge, followed by the characteristic cough and noisy inspiration that typically awaken the child at night.

The child may become anxious, which leads to increasing dyspnea and transient cyanosis.

Inspection may disclose labored breathing with retractions and clammy skin.

Palpation may reveal a rapid pulse rate. These severe signs diminish after several hours but reappear in a milder form on the next one or two nights.

Diagnostic test results

Blood cultures can distinguish bacterial from viral infections.

Laryngoscopy may reveal inflammation and obstruction in epiglottal and laryngeal areas.

Throat cultures can rule out diphtheria.

Throat cultures can also identify infecting organisms and their sensitivity to antibiotics when bacterial infection is the cause.

X-rays of the neck may show upper airway narrowing and edema in subglottic folds.

Treatment

For most children with croup, home care with rest, cool humidification during sleep, and antipyretic drugs such as acetaminophen (Tylenol) relieve signs and symptoms. However, respiratory distress that interferes with oral hydration usually requires hospitalization and parenteral fluid replacement to prevent dehydration. If the patient has croup from a bacterial infection, he needs antibiotic therapy. Oxygen therapy may also be required.

For moderately severe croup, aerosolized racemic epinephrine may temporarily reduce airway swelling. Intubation is performed only if other means of preventing respiratory failure are unsuccessful.

Corticosteroids reduce subglottic edema and inflammation. Dexamethasone (Decadron) given in a single dose early in the course of croup allows a shorter hospital stay and reduces cough, dyspnea and, commonly, the need for intubation.

Nursing interventions

Monitor cough and breath sounds, hoarseness, severity of retractions, inspiratory stridor, cyanosis, respiratory rate and character (especially prolonged and labored respirations), restlessness, fever, and heart rate.

Keep the child as quiet as possible but avoid sedation, which may depress respiration. If the patient is an infant, position him in an infant seat or prop him up with a pillow; place an older child in Fowler’s position. If an older child requires a cool-mist tent to help him breathe, describe it to him and his parents and explain why it’s needed.

Change bed linens as necessary to keep the patient dry.

Control the patient’s energy output and oxygen demand by providing age-appropriate diversional activities to keep him quietly occupied.

If possible, isolate patients suspected of having RSV and parainfluenza infections. Wash your hands carefully before leaving the room to avoid transmitting germs to other patients, particularly infants.

Control fever with sponge baths and antipyretics. Keep a hypothermia blanket on hand if the patient’s temperature rises above 102° F (38.9° C). Watch for seizures in infants and young children with high fevers. Give I.V. antibiotics as ordered.

Relieve sore throat with soothing, water-based ices, such as fruit sherbet and ice pops. Avoid thicker, milk-based fluids if the patient has thick mucus or swallowing difficulties. Apply petroleum jelly or another ointment around the nose and lips to decrease irritation from nasal discharge and mouth breathing.

Institute measures to prevent the patient’s crying, which increases respiratory distress. As necessary, adapt treatment to conserve the patient’s energy and to include parents, who can provide reassurance.

Reassure the parents that they made the right decision by bringing their child to the emergency department, especially at night when the night air may improve the child’s breathing significantly, leaving the parents wondering if they over-reacted.

Watch for signs of complete airway obstruction, such as increased heart and respiratory rates, use of respiratory accessory muscles in breathing, nasal flaring, and increased restlessness. (See Croup teaching topics.)

DISCHARGE TEACHING

Because this disease primarily affects young children, patient teaching usually centers on the parents.

Warn parents that ear infections and pneumonia may complicate croup. These disorders may follow croup about 5 days after recovery. Urge the parents to seek immediate medical attention if the patient has an earache, productive cough, high fever, or increased shortness of breath.

Teach the parents effective home care. Suggest the use of a cool humidifier (vaporizer). To relieve croupy spells, tell parents to carry the child into the bathroom, shut the door, and turn on the hot water. Breathing in warm, moist air quickly eases an acute spell of croup.

EPIGLOTTIDITIS

Epiglottiditis, an acute inflammation of the epiglottis and surrounding area, is a life-threatening emergency that rapidly causes edema and induration. If untreated, epiglottiditis results in complete airway obstruction. Epiglottiditis can occur from infancy to adulthood in any season. It’s fatal in 8% to 12% of patients, typically children ages 2 to 8.

Pathophysiology

Epiglottiditis usually results from infection with Haemophilus influenzae type B and, occasionally, pneumococci or group A streptococci. Epiglottiditis is becoming more rare.

Complications

Airway obstruction

Death

AIRWAY CRISIS

Epiglottiditis can progress to complete airway obstruction within minutes. To prepare for this medical emergency, keep these tips in mind.

Watch for increasing restlessness, tachycardia, fever, dyspnea, and intercostal and substernal retractions. These are warning signs of total airway obstruction and the need for an emergency tracheotomy.

Keep the following equipment available at the patient’s bedside in case of sudden, complete airway obstruction: a tracheotomy tray, endotracheal tubes, a manual resuscitation bag, oxygen equipment, and a laryngoscope with blades of various sizes.

Remember that using a tongue blade or throat culture swab can initiate sudden, complete airway obstruction.

Before examining the patient’s throat, arrange for trained personnel (such as an anesthesiologist) to be present in case the patient requires insertion of an emergency airway.

Assessment findings

The patient or his parents may report an earlier upper respiratory tract infection.

Additional complaints include sore throat, dysphagia, and the sudden onset of a high fever.

On inspection, the patient may be febrile, drooling, pale or cyanotic, restless, apprehensive, and irritable.

You may also observe nasal flaring.

The patient may sit in a tripod position: upright, leaning forward with the chin thrust out, mouth open, and tongue protruding. This position helps relieve severe respiratory distress.

The patient’s voice usually sounds thick and muffled.

Because manipulation may trigger sudden airway obstruction, attempt throat inspection only when immediate intubation is needed and can be performed. (See Airway crisis.)

The patient’s throat appears red and inflamed.

Auscultation of the lung fields may reveal rhonchi and diminished breath sounds, usually transmitted from the upper airway.

Diagnostic test results

Direct laryngoscopy reveals the hallmark of acute epiglottiditis: a swollen, beefy-red epiglottis. The throat examination should follow X-rays and, in most cases, shouldn’t be performed if significant obstruction is suspected or if immediate intubation isn’t possible.

Lateral neck X-rays show an enlarged epiglottis and distended hypopharynx.

Additional X-rays of the chest and cervical trachea help to confirm the diagnosis.

Treatment

A patient with acute epiglottiditis and airway obstruction requires emergency hospitalization. Place the patient in a cool-mist tent with added oxygen. If complete or near-complete airway obstruction occurs, he may also need emergency endotracheal intubation or a tracheotomy. Arterial blood gas (ABG) analysis or pulse oximetry may be used to assess his progress.

Treatment may also include parenteral fluids to prevent dehydration when the disease interferes with swallowing and a 10-day course of parenteral antibiotics—usually ampicillin (Principen). If the patient is allergic to penicillin or could have ampicillin-resistant endemic H. influenzae, chloramphenicol (Chloromycetin) or another antibiotic may be prescribed.

Corticosteroids may be prescribed to reduce edema during early treatment. Oxygen therapy also may be used.

Keep in mind that preventive measures should be taken. In the late 1980s, the American Academy of Pediatrics recommended that all children receive the Haemophilus b conjugate (Hib) vaccine, and it remains on the recommended schedule of immunizations today. Begin Hib vaccine immunization at age 2 months and continue for three or four doses, depending on the manufacturer. Since the introduction of the Hib vaccine, the incidence of epiglottiditis has declined dramatically.

Nursing interventions

Place the patient in a sitting position to ease his respiratory difficulty unless he finds another, more comfortable position.

Monitor pulse oximetry.

Place the patient in a cool-mist tent. Change the sheets frequently because they quickly become saturated.

Encourage the parents to remain with their child. Offer reassurance and support to relieve family members’ anxiety and fear.

Monitor the patient’s temperature, vital signs, and respiratory rate and pattern frequently. Also monitor ABG (to detect hypoxia and hypercapnia) and pulse oximetry values (to detect decreasing oxygen saturation). Report changes.

Observe the patient continuously for signs of impending airway closure, which may develop at any time.

Calm the patient during X-rays of his chest and cervical trachea.

Minimize external stimuli.

Start an I.V. line for antibiotic therapy and fluid replacement if the patient can’t maintain adequate fluid intake. Draw blood for laboratory analysis, as ordered.

Keep tracheostomy equipment at the bedside.

Record intake and output precisely to monitor and prevent dehydration.

If the patient has a tracheostomy, anticipate his needs because he can’t cry or call out. Provide emotional support. Reassure him and his family that a tracheostomy is a short-term intervention (usually 4 to 7 days). Monitor the patient for signs of secondary infection, including increasing temperature, increasing pulse rate, and hypotension. (See Epiglottiditis teaching topics.)

DISCHARGE TEACHING

Inform the patient and his family that epiglottal swelling usually subsides after 24 hours of antibiotic therapy. The epiglottis usually returns to normal size within 72 hours.

If the patient’s home care regimen includes oral antibiotic therapy, emphasize the need for completing the entire prescription. Explain proper administration. Discuss drug storage, dosage, adverse effects, and whether the medication can be taken with food or milk.

If the patient should require the Haemophilus b conjugate vaccine, discuss the rationale for immunization, and help the family obtain the vaccine.

PHARYNGITIS

Pharyngitis, the most common throat disorder, is an acute or chronic inflammation of the pharynx. It’s widespread among adults who live or work in dusty or dry environments, use their voices excessively, habitually use tobacco or alcohol, or suffer from chronic sinusitis, persistent coughs, or allergies. Uncomplicated pharyngitis usually subsides in 3 to 10 days.

Beta-hemolytic streptococci, which cause 15% to 20% of the cases of acute pharyngitis, may precede the common cold or other communicable diseases. Chronic pharyngitis is usually an extension of nasopharyngeal obstruction or inflammation.

Viral pharyngitis accounts for about 70% of acute pharyngitis cases.

Pathophysiology

Pharyngitis may occur as a result of a virus, such as rhinovirus, coronavirus, adenovirus, influenza, and parainfluenza. Mononucleosis can also cause pharyngitis. In children, streptococcal bacteria commonly cause pharyngitis. Fungal pharyngitis can develop with prolonged use of an antibiotic in an immunosuppressed patient, such as one with human immunodeficiency virus. Gonococcal pharyngitis is caused by release of a toxin produced by Corynebacterium diphtheriae.

Complications

Otitis media

Sinusitis

Mastoiditis

Rheumatic fever

Nephritis

Assessment findings

Typically, the patient complains of a sore throat and slight difficulty swallowing; swallowing saliva hurts more than swallowing food.

The patient may also complain of a sensation of a lump in the throat, a constant and aggravating urge to swallow, a headache,

and muscle and joint pain (especially in bacterial pharyngitis).

Assessment of vital signs may reveal mild fever.

On inspection, the posterior pharyngeal wall appears fiery red, with swollen, exudate-flecked tonsils and lymphoid follicles.

If the patient has bacterial pharyngitis, the throat is acutely inflamed, with patches of white and yellow follicles.

The tongue may be strawberry red in color.

Neck palpation may reveal enlarged, tender cervical lymph nodes.

Diagnostic test results

Computed tomography scan is helpful in identifying the location of abscesses.

Rapid strep tests generally detect group A streptococcal infections, but they miss the fairly common streptococcal groups C and G.

Throat culture may be used to identify the bacterial organisms causing the inflammation, but it may not detect other causative organisms.

White blood cell (WBC) count is used to determine atypical lymphocytes; total WBC count is elevated.

Treatment

Based on the patient’s symptoms, treatment for acute viral pharyngitis consists mainly of rest, warm saline gargles, throat lozenges containing a mild anesthetic, plenty of fluids, and an analgesic, as needed. If the patient can’t swallow fluids, he may need hospitalization for I.V. hydration.

Bacterial pharyngitis requires rigorous treatment with penicillin (or another broad-spectrum antibiotic if the patient is allergic to penicillin) because streptococcus is the chief infecting organism. Continue antibiotic therapy for 48 hours after visible signs of infection have disappeared or for at least 7 to 10 days.

An antifungal is used to treat fungal pharyngitis. An equine antitoxin is given for diphtheria pharyngitis.

An antifungal is used to treat fungal pharyngitis. An equine antitoxin is given for diphtheria pharyngitis.

DISCHARGE TEACHING

If the patient has acute bacterial pharyngitis, emphasize the importance of completing the full course of antibiotic therapy. Tell him to call the physician if he experiences an adverse reaction.

Teach the patient with chronic pharyngitis how to minimize sources of throat irritation in the environment—by using a bedside humidifier, for example. Refer him to a self-help group to stop smoking, if appropriate.

Inform the patient and his family that in the case of a positive streptococcal infection, the family should undergo throat cultures, regardless of the presence or absence of symptoms. Those with positive cultures require penicillin therapy.

Teach the patient to avoid using irritants, such as alcohol, which may worsen symptoms.

Chronic pharyngitis requires the same supportive measures as acute pharyngitis, but with greater emphasis on eliminating the underlying cause such as an allergen.

Preventive measures include humidifying the air and avoiding excessive exposure to air conditioning. In addition, urge patients who smoke to stop.

Nursing interventions

Give an analgesic and warm saline gargles, as ordered and as appropriate.

Encourage the patient to drink fluids (up to 21/2 qt [2.5 L] per day). Monitor intake and output scrupulously, and watch for signs of dehydration (cracked lips, dry mucous membranes, low urine output, poor skin turgor). Provide meticulous mouth care to prevent dry lips and oral pyoderma.

Obtain throat cultures, and give an antibiotic, as ordered.

Maintain a restful environment, especially if the patient is febrile, to conserve energy.

Advise a soft, light diet with plenty of liquids to combat the commonly experienced anorexia. An antiemetic can be given before eating, if ordered.

Examine the skin twice per day for possible drug sensitivity rashes or for rashes indicating a communicable disease.

Give an antitussive, as ordered, if the patient has a cough.

Give an analgesic, as ordered. (See Pharyngitis teaching topics.)

PLEURAL EFFUSION AND EMPYEMA

The pleural space normally contains a small amount (about 20 ml) of extracellular fluid that lubricates the pleural surfaces. If fluid accumulates as a result of increased production or inadequate removal, pleural effusion occurs. Empyema is a type of pleural effusion in which pus and necrotic tissue accumulate in the pleural space. Blood (hemothorax) and chyle (chylothorax) may also collect in this space.

The incidence of pleural effusion increases with heart failure (the most common cause), parapneumonia, cancer, and pulmonary embolism.

Pathophysiology

A transudative pleural effusion—an ultrafiltrate of plasma containing a low concentration of protein—may result from heart failure, hepatic disease with ascites, peritoneal dialysis, hypoalbuminemia, and disorders that increase intravascular volume.

The effusion stems from an imbalance of osmotic and hydrostatic pressures. Normally, the balance of these pressures in parietal pleural capillaries causes fluid to move into the pleural space; balanced pressure in visceral pleural capillaries promotes reabsorption of this fluid. However, when excessive hydrostatic pressure or decreased osmotic pressure causes excessive fluid to pass across intact capillaries, a transudative pleural effusion results.

Exudative pleural effusions can result from tuberculosis (TB), subphrenic abscess, pancreatitis, bacterial or fungal pneumonitis or empyema, cancer, parapneumonia, pulmonary embolism (with or without infarction), collagen disease (lupus erythematosus and rheumatoid arthritis), myxedema, intra-abdominal abscess, esophageal perforation, and chest trauma.

Such an effusion occurs when capillary permeability increases, with or without changes in hydrostatic and colloid osmotic pressures, allowing protein-rich fluid to leak into the pleural space.

Empyema usually stems from an infection in the pleural space. The infection may be idiopathic or may be related to pneumonitis, carcinoma, perforation, penetrating chest trauma, or esophageal rupture.

Complications

Atelectasis

Hypoxemia, respiratory acidosis, or thoracic shift (in large pleural effusions)

Infection

Assessment findings

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree