11 Identifying the Patient at High Risk for Acute Coronary Syndrome

Plaque Rupture and “Immediate Risk”

Etiology and Pathogenesis

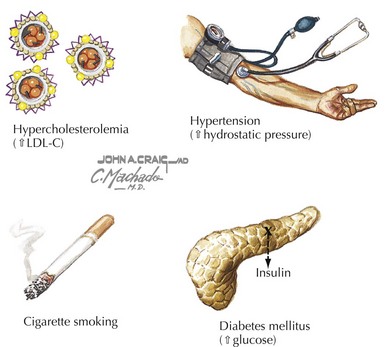

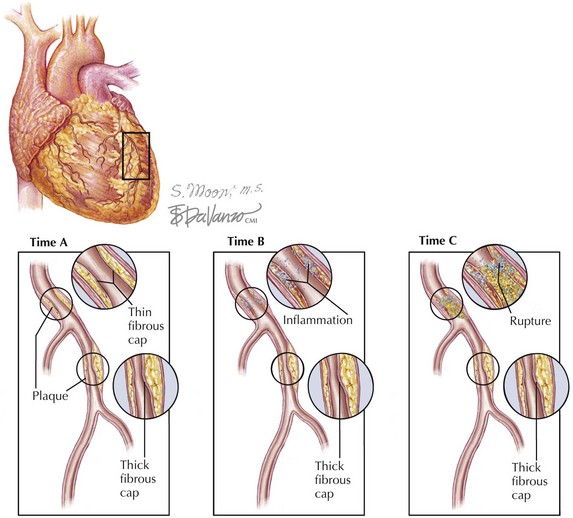

The earliest evidence of CAD is present in many Americans during late adolescence, based on autopsy studies. Clinically detectable CAD develops over decades, often silently. Multiple risk factors contribute to the development of atherosclerosis: hypertension, diabetes mellitus, smoking, age, and hyperlipidemia (Fig. 11-1). Acute coronary syndromes occur following rupture of an atherosclerotic plaque and the development of a subocclusive or totally occlusive thrombus that may lead to unstable angina or acute myocardial infarction. Many triggers for plaque rupture have been proposed, ranging from hemodynamic stress to the presence of a generalized inflammatory state to neurohormonal influences. However, the precise factors that lead to the rupture of specific plaques in a given individual have yet to be defined.

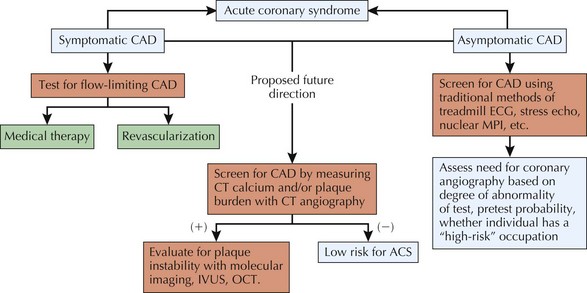

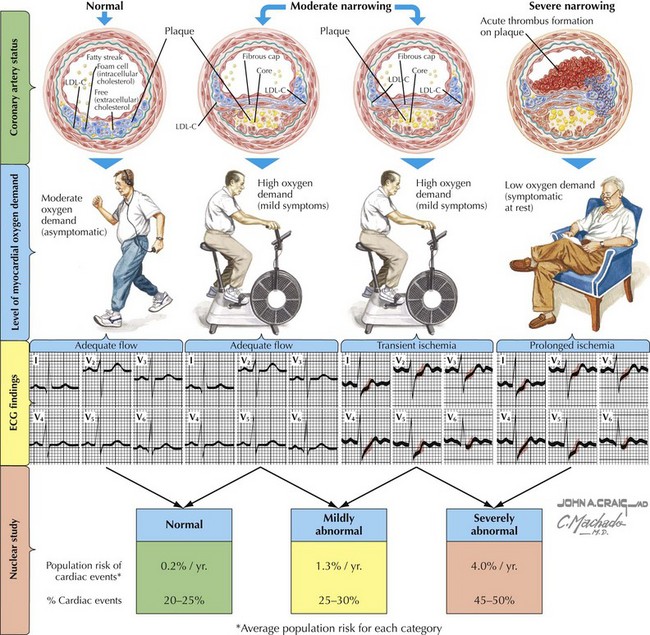

The principal problem with current methods of screening for CAD is that the majority of plaques that rupture and cause acute coronary syndrome are less than 70% in transluminal diameter and do not cause hemodynamically significant coronary obstruction until they rupture (Fig. 11-2). Thus, they are very difficult to detect with screening mechanisms that rely on reduced distal blood flow to cause changes detectable by the test (e.g., ischemic ECG changes, hypocontractility on echocardiogram, perfusion defects on nuclear scans). In fact, what many of these tests detect are narrowed, hemodynamically significant lesions that are stable and not prone to rupturing or causing acute coronary syndrome. Therefore, newer techniques to identify the vulnerable plaque prone to rupture are the focus of much research.

Clinical Presentation

There are many reasons why screening for CAD has become common clinical practice, ranging from better education of the public about the dangers of CAD (resulting in more patient-initiated requests for screening) to the possibility that a noninvasive assessment will preclude a need for cardiac catheterization. In addition, physicians are eager to detect early coronary disease in their patients deemed to be at risk, so that they may intervene before the onset of symptoms or a major cardiac event (Fig. 11-3).

Diagnostic Approach

Clinical Epidemiology

It is important to understand Bayes’ theorem as it applies to medical screening tests. The post-test probability of CAD depends on the pre-test probability of disease and the sensitivity and specificity of the test being used. Testing at very low or very high pre-test probabilities may not actually change clinical decision making (see Chapter 1). In particular, for screening asymptomatic patients for CAD, patients with a very low pre-test probability are more likely to have a false-positive test result than a true-positive test result, especially if the test’s specificity is poor.

Risk Scores

Framingham Risk Score

There are many well-established risk factors for the development of CAD: age, smoking, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, male sex, diabetes, obesity, and physical inactivity, among others. Epidemiologic studies have allowed researchers to develop risk prediction calculators that determine the risk of coronary heart disease events based on the presence of these risk factors. One of the more commonly used risk calculators is based on the Framingham population. It provides an estimate of the 10-year risk of a cardiac event (see “National Cholesterol Education Program. Risk Assessment Tool for Estimating 10-Year Risk of Developing Hard CHD,” under “Additional Resources”).

Screening Tests

Exercise Testing—Exercise ECG

Exercise-ECG testing has been widely adopted for screening for CAD in asymptomatic adults. Adding exercise to ECG monitoring increases the sensitivity of the test by unmasking ischemia not detectable at rest. A positive test is reflected by at least 1 mm of flat or down-sloping ST depression. Exercise-ECG testing can only be performed in those who can exercise and do not have underlying ECG abnormalities at rest that would prevent interpretation (left bundle branch block, ST depression at rest, or a paced ventricular rhythm) (Fig. 11-4).

Figure 11-4 The degrees of flow-limiting atherosclerosis and plaque rupture.

ECG, electrocardiogram; LDL, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol.