I-K

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis

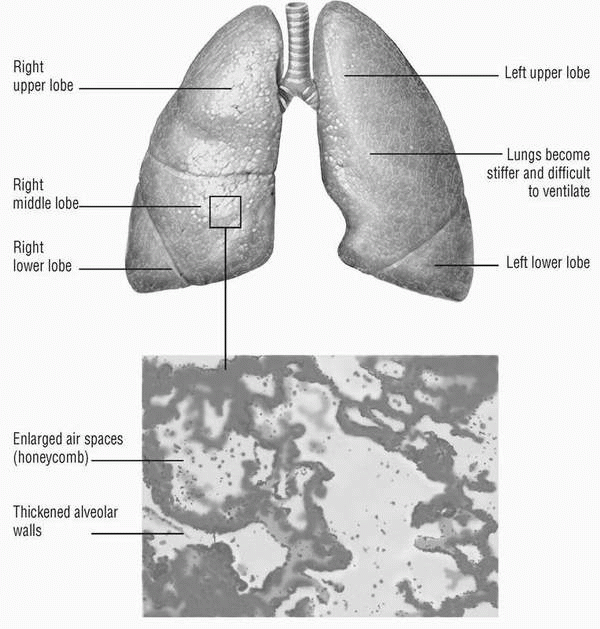

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is a chronic and usually fatal interstitial pulmonary disease. About 50% of patients with IPF die within 5 years of diagnosis. Once thought to be a rare condition, it’s now diagnosed with much greater frequency. IPF has been known by several other names over the years, including cryptogenic fibrosing alveolitis, diffuse interstitial fibrosis, idiopathic interstitial pneumonitis, and Hamman-Rich syndrome.

CAUSES AND INCIDENCE

IPF results from a cascade of events that involve inflammatory, immune, and fibrotic processes in the lung. However, despite many studies and hypotheses, the stimulus that begins the progression remains unknown. Speculation has revolved around viral and genetic causes, but no strong evidence has been found to support either theory. However, it’s clear that chronic inflammation plays an important role.

Inflammation develops the injury, and fibrosis ultimately distorts and impairs the structure and function of the alveolocapillary gas exchange surface. Interstitial inflammation consists of an alveolar septal infiltrate of lymphocytes, plasma cells, and histiocytes. Fibrotic areas are composed of dense acellular collagen. Areas of honeycombing form, made up of cystic fibrotic air spaces, frequently lined with bronchiolar epithelium and filled with mucus. Smooth-muscle hyperplasia may occur in areas of fibrosis and honeycombing. (See End-stage idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis.)

IPF occurs in men slightly more often than in women and in smokers more often than in nonsmokers.

IPF occurs most commonly in people between the ages of 50 to 70.

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

The usual presenting signs and symptoms of IPF are dyspnea and a dry, hacking, often paroxysmal cough. Most patients have had these for anywhere from several months to 2 years before seeking medical help. Other signs and symptoms include:

• cyanosis

• end-expiratory crackles, especially in the bases of the lungs (usually heard early in the disease)

• bronchial breath sounds (typically appear later in the disease, when airway consolidation develops)

• rapid, shallow breathing, especially with exertion

• clubbing of fingers and toes

• pulmonary hypertension (augmented S2 and S3 gallop)

• profound hypoxemia and severe, debilitating dyspnea (in advanced disease).

COMPLICATIONS

• Respiratory failure

• Chronic hypoxemia

• Pulmonary hypertension

• Cor pulmonale

• Polycythemia

DIAGNOSIS

Diagnosis begins with a thorough patient history to exclude more common causes of interstitial lung disease. A lung biopsy using a thoracoscope or bronchoscope—an improvement over the open lung

biopsies that were previously performed to diagnose IPF—helps in the diagnosis. Histologic features of the biopsy tissue depend on the stage of the disease as well as on other factors that aren’t yet completely understood. Typically, the alveolar walls appear swollen with chronic inflammatory cellular infiltrate composed of mononuclear cells and polymorphonuclear leukocytes. In the early stages, intra-alveolar inflammatory cells may be found. As the disease progresses, excessive collagen and fibroblasts fill the interstitium. In advanced stages, alveolar walls are destroyed, replaced by honeycombing cysts.

biopsies that were previously performed to diagnose IPF—helps in the diagnosis. Histologic features of the biopsy tissue depend on the stage of the disease as well as on other factors that aren’t yet completely understood. Typically, the alveolar walls appear swollen with chronic inflammatory cellular infiltrate composed of mononuclear cells and polymorphonuclear leukocytes. In the early stages, intra-alveolar inflammatory cells may be found. As the disease progresses, excessive collagen and fibroblasts fill the interstitium. In advanced stages, alveolar walls are destroyed, replaced by honeycombing cysts.

Chest X-rays may show one of four distinct patterns: interstitial, reticulonodular, ground glass, or honeycomb. Although chest X-rays help identifying the presence of an abnormality, they don’t correlate well with histologic findings or pulmonary function tests in determining the severity of the disease. They also don’t help distinguish inflammation from fibrosis. However, serial X-rays may help track the progression of the disease.

High-resolution computed tomography scans provide superior views of the four patterns seen on X-ray film and are used routinely to help establish the diagnosis of IPF. Research is currently underway to determine whether the four patterns of abnormality seen on these scans correlate with responsiveness to treatment.

Pulmonary function tests show reductions in vital capacity and total lung capacity as well as impaired diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide. Arterial blood gas (ABG) analysis and pulse oximetry reveal hypoxemia, which may be mild when the patient is at rest early in the disease but may become severe later in the disease. Oxygenation always deteriorates—usually to a severe level—with exertion. Serial pulmonary function tests (especially carbon monoxide diffusing capacity) and ABG values may help track the course of the disease and the patient’s response to treatment.

TREATMENT

No known cure exists for IPF, although interferon-gamma-1B has shown some promise in treating the disease. Lung transplantation may be successful for younger, otherwise healthy individuals. In the early stages of the disease, oxygen therapy can prevent the problems related to dyspnea and tissue hypoxia, although it can’t change the pathology of the disease process. The patient may require little or no supplemental oxygen while at rest initially, but he’ll need more as the disease progresses and during exertion.

Drugs

• Glucocorticoids such as prednisone (Deltasone, Orasone, Sterapred) to reverse increased capillary permeability and suppress polymorphonuclear activity, decreasing inflammation

• Immunosuppressants, such as azathioprine (Imuran) and cyclophosphamide (Cytoxan), to lower autoimmune activity and reduce inflammation when corticosteroids aren’t effective

• Antiviral cytokines such as interferon gamma-1b (Actimmune) to stimulate the immune system and inhibit proliferation of fibroblasts and to suppress production of the connective-tissue matrix protein

• Antioxidants such as N-acetylcysteine (Acetadote) to restore glutathione levels in lung tissue and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid

SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS

• Explain all diagnostic tests to the patient, who may feel anxious and frustrated over the many tests required to establish the diagnosis.

• Monitor the patient’s oxygenation level, both at rest and with exertion. The physician may prescribe one oxygen flow rate for use when the patient is at rest and a higher one for use during exertion to maintain adequate oxygenation. Tell the patient to increase his oxygen flow rate to the appropriate level for exercise.

• As IPF progresses, keep in mind that the patient will require more oxygen. He may need a nonrebreathing mask to supply high oxygen percentages. Eventually, maintaining adequate oxygenation may become impossible, despite maximum oxygen flow.

• Because most patients will need oxygen at home, make appropriate referrals to discharge planners, respiratory care practitioners, and home equipment vendors to ensure continuity of care.

• Teach breathing, relaxation, and energy conservation techniques to help the patient manage severe dyspnea.

• Encourage the patient to be as active as possible, and refer him to a pulmonary rehabilitation program.

• Monitor the patient for adverse reactions to drug therapy.

• Teach the patient about prescribed medications, especially adverse effects. Teach the patient and family members infection prevention techniques.

• Encourage good nutritional habits. The patient may require small, frequent meals with high nutritional value if dyspnea interferes with eating.

• Provide emotional support for the patient and family members as they deal with the patient’s increasing disability, dyspnea, and probable death.

Influenza

Influenza—also called the grippe or the flu—is an acute, highly contagious infection of the respiratory tract that results from three different types of myxovirus influenzae. It occurs sporadically or in epidemics (usually during the colder months). Epidemics tend to peak within 3 weeks of initial cases and subside within a month.

Although influenza affects all age groups, its incidence is highest in

schoolchildren. However, its effects are most severe in the very young, the elderly, and those suffering from chronic disease. In these groups, influenza may even lead to death. The catastrophic pandemic of 1918 was responsible for an estimated 20 million deaths. The most recent pandemics (in 1957, 1968, and 1977) began in mainland China.

schoolchildren. However, its effects are most severe in the very young, the elderly, and those suffering from chronic disease. In these groups, influenza may even lead to death. The catastrophic pandemic of 1918 was responsible for an estimated 20 million deaths. The most recent pandemics (in 1957, 1968, and 1977) began in mainland China.

CAUSES AND INCIDENCE

Transmission of influenza occurs through inhalation of respiratory droplets from an infected person or by indirect contact with a contaminated object, such as a drinking glass or other item contaminated with respiratory secretions. The influenza virus then invades the epithelium of the respiratory tract, causing inflammation and desquamation. (See How influenza viruses multiply.)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree