Chapter 27

Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy

1. What is hypertrophic cardiomyopathy?

2. What is the prevalence of HCM?

3. What are the genetic mutations that cause HCM, and how are they transmitted?

4. Who should be screened for HCM?

Patients with known HCM mutations, but without evidence of disease, and first-degree relatives of patients with HCM should be screened. Screening is performed primarily with history, physical examination, 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG), and two-dimensional echocardiography. Traditionally, screening was performed on a 12- to 18-month basis, usually beginning by age 12 until age 18 to 21. However, it is now recognized that development of the HCM phenotype uncommonly can occur later in adulthood. Therefore, the current recommendation is to extend clinical surveillance into adulthood at about 5-year intervals or to undergo genetic testing (Table 27-1).

TABLE 27-1

CLINICAL SCREENING STRATEGIES FOR DETECTION OF HYPERTROPHIC CARDIOMYOPATHY IN FAMILIES∗

<12 years old

12 to 18-21 years old

>18-21 years old

Probably approximately every 5 years or more frequent intervals with a family history of late-onset hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and/or malignant clinical course

∗In the absence of laboratory-based genetic testing.

From Maron BJ, Seidman JG, Seidman CE: Proposal for contemporary screening strategies in families with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol 44:2125-2132, 2004.

5. Who should undergo genetic testing?

6. What are the histologic characteristics of HCM?

The histology of HCM is characterized by hypertrophy of cardiac myocytes and myocardial fiber disarray. The abnormal myocytes contain bizarrely shaped nuclei and are arranged in disorganized patterns. The volume of the interstitial collagen matrix is greatly increased, and the arrangement of the matrix components is also disorganized. Myocardial disarray is seen in substantial portions of hypertrophied and nonhypertrophied LV myocardium. Almost all HCM patients have some degree of disarray, and in the majority, at least 5% of the myocardium is involved.

7. What are the common types of HCM?

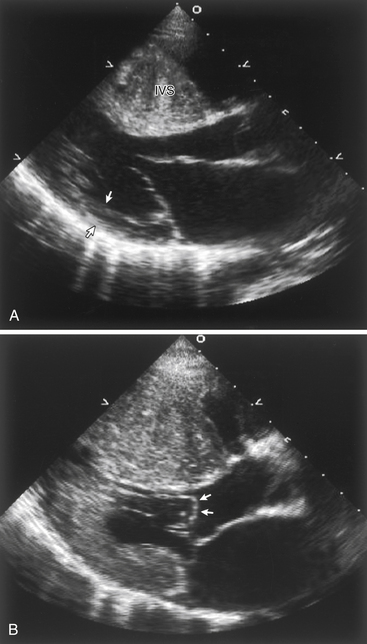

The distribution and severity of LV hypertrophy in patients with HCM can vary greatly. Even first-degree relatives, with the same genetic mutation, usually show different patterns of hypertrophy. Various patterns of LV hypertrophy have been reported. The most common site of hypertrophy is the anterior interventricular septum (Fig. 27-1), which is seen in more than 80% of HCM patients and is known as asymmetrical septal hypertrophy (ASH). Concentric LV hypertrophy, with maximal thickening at the level of the papillary muscles, is seen in 8% to 10% of patients with HCM. A variant with primary involvement of the apex (apical HCM) is common in Japan and rare in the U.S. (less than 2%) and is characterized by spadelike deformity of the LV.

Figure 27-1 A, Echocardiogram of a patient with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, demonstrating a markedly thickened interventricular septum compared with the normal wall thickness of the posterior wall (arrows). B, During systole, there is systolic anterior motion (SAM) and buckling of the anterior mitral leaflet (arrows), obstructing the left ventricular outflow tract.

8. What are the most common symptoms in patients with HCM?

Present in more than 90% of symptomatic patients

Present in more than 90% of symptomatic patients

Caused mainly by LV diastolic dysfunction with impaired filling caused by abnormal relaxation and increased chamber stiffness

Caused mainly by LV diastolic dysfunction with impaired filling caused by abnormal relaxation and increased chamber stiffness

Also caused by dynamic LV outflow tract (LVOT) obstruction (see Fig. 27-1) leading to elevated intraventricular pressures.

Also caused by dynamic LV outflow tract (LVOT) obstruction (see Fig. 27-1) leading to elevated intraventricular pressures.

May occur in both obstructive and nonobstructive HCM

May occur in both obstructive and nonobstructive HCM

Caused by a mismatch of supply and demand in myocardial perfusion

Caused by a mismatch of supply and demand in myocardial perfusion

Several mechanisms have been proposed, including increased muscle mass and wall stress, decreased coronary perfusion pressure secondary to LV outflow obstruction, elevated diastolic filling pressures, systolic compression of large intramural coronary arteries, inadequate capillary density, impaired vasodilatory reserve, and abnormally narrowed small intramural coronary arteries

Several mechanisms have been proposed, including increased muscle mass and wall stress, decreased coronary perfusion pressure secondary to LV outflow obstruction, elevated diastolic filling pressures, systolic compression of large intramural coronary arteries, inadequate capillary density, impaired vasodilatory reserve, and abnormally narrowed small intramural coronary arteries

9. How is HCM differentiated from athlete’s heart?

Long-term athletic training can lead to cardiac hypertrophy, known as athlete’s heart. This clinically benign physiologic condition must be differentiated from HCM, because HCM is the most common cause of sudden death in competitive athletes. Clinical parameters that support the diagnosis of HCM instead of athlete’s heart are asymmetric hypertrophy greater than 16 mm, LV end-diastolic dimension less than 45 mm, enlarged left atrium, impaired LV relaxation on Doppler mitral valve inflow parameters and tissue Doppler echocardiography, absent response to deconditioning (e.g., hypertrophy does not regress with absence of exercise), family history of HCM, and sarcomeric protein mutation identified by genetic testing. These parameters are summarized in Table 27-2.