15.2 PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

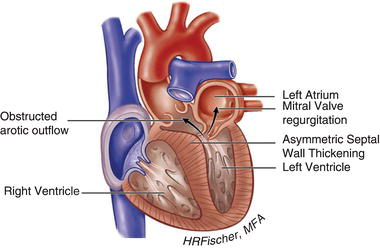

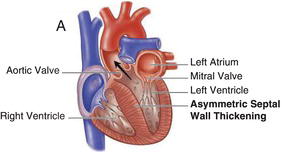

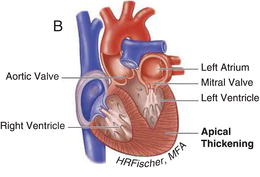

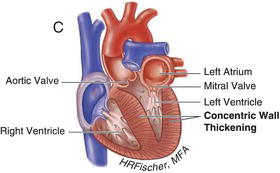

HCM is inherited in an autosomal dominant fashion with a highly variable degree of penetrance. It is primarily the result of mutations in genes encoding cardiac sarcomere proteins. HCM is defined by a hypertrophied, non-dilated left ventricle in the absence of another cardiac or systemic disease capable of producing the degree of hypertrophy present. It can manifest as negligible (13–15 mm) to significant (>30 mm) hypertrophy and can be associated with LVOT obstruction, as well as varying degrees of fibrosis and myocyte disarray. The hypertrophy is most often asymmetric, preferentially involving the basal intraventricular septum. However, hypertrophy may involve other regions of the intraventricular septum, the left ventricular free walls and/or apex and even the right ventricle. Figures 15.1 and 15.2 demonstrate examples of HCM anatomic variants.

Figure 15.1 Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy with left ventricular outflow tract obstruction. (See Color plate 15.1).

Figure 15.2 Nonobstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. A Heart with asymmetric septal wall thickening that is not associated with outflow tract obstruction. B Apical hypertrophy. C Heart with concentric left ventricular hypertrophy. (See Color plate 15.2).

15.3 PATHOPHYSIOLOGY AND CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

The clinical manifestations of HCM range from an asymptomatic lifelong course to advanced heart failure refractory to pharmacotherapy. In addition, a subset of the HCM population is at risk for atrial and ventricular tachyarrhythmias. Because of its heterogeneous clinical course and phenotypic expression, as well as its most notorious and devastating complication, sudden cardiac arrest, HCM presents many management dilemmas for practitioners involved in their care.

Dyspnea is a common symptom that typically occurs with exertion and may result from a combination of the following etiologies: (1) high pulmonary venous pressure due to diastolic dysfunction; (2) LV outflow tract obstruction and/or mitral regurgitation; (3) decreased cardiac output due to the low end-diastolic volume of a noncompliant left ventricle; and (4) myocardial ischemia. Angina may occur in the absence of epicardial coronary artery disease and is likely the result of an inability of the coronary microcirculation to meet the demands of the hypertrophied myocardium.

Those patients with LV outflow tract obstruction characteristically have asymmetric hypertrophy affecting the basal intraventricular septum and resultant systolic anterior motion (SAM) of the mitral valve with varying degrees of mitral regurgitation. In some patients, outflow tract obstruction is present at rest, while in others can be provoked by maneuvers that decrease preload or increase contractility including Valsalva, standing from a squatting position, and exercise (see Chapter 1, Cardiovascular History and Physical Examination). About one-third of patients with HCM have resting obstruction ( ≥ 30 mmHg), while another one-third have dynamic outflow tract obstruction provoked by exercise. Systolic septal bulging into the LVOT, malposition of the anterior papillary muscle, intrinsic mitral valve abnormalities, drag forces, and hyperdynamic left ventricular contraction (causing the Venturi effect) may contribute to development of an LVOT pressure gradient. Intrinsic abnormalities of the mitral apparatus including leaflet thickening, elongated or redundant leaflets, and anomalous papillary muscle or chordal insertion occur in an estimated 20% of patients with HCM and can also contribute to the severity of mitral regurgitation and increased symptomology.

Table 15.1 Risk Factors for Sudden Cardiac Death (Primary Prevention).

| Wall thickness ≥30 mm Unexplained syncope Family history of sudden cardiac death in a first-degree relative under the age of 40 years Spontaneous NSVT (≥3 beats at a rate >120 bpm on 24- or 48-hour ECG monitoring) Abnormal blood pressure response to exercise (inadequate rise or frank drop in blood pressure) in those <40 years of age |

Diastolic dysfunction with preserved ejection fraction is an almost universal feature of the disease resulting from a stiff and noncompliant left ventricle. In patients with and without LVOT obstruction, left ventricular systolic function is generally normal or increased, except in a small subset (<5%) who may develop systolic dysfunction in the so-called “end-stage,” leading to significant functional decline.