23.2 ASSOCIATION WITH CARDIOVASCULAR OUTCOMES

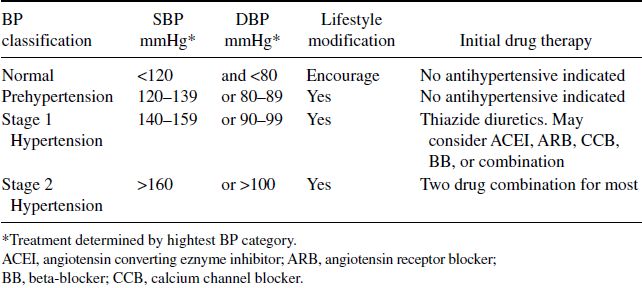

The association between BP and cardiovascular disease (CVD) is continuous across multiple patient populations. The more elevated a patient’s BP, the greater the risk for heart attack, stroke, and kidney disease. The Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure (JNC VII) released in 2003, categorized hypertension into four primary categories to increase the awareness of high blood pressure and to stratify and help guide therapeutics (Table 23.1).

While antihypertensive trials have shown some variability in the degree of benefit, almost all have demonstrated some clinical benefits of treating hypertension with regards to outcomes including heart attack, stroke, and heart failure. On average, antihypertensive therapy has been associated with reductions in the incidence of heart attack by 25–30%, stroke by 35–40%, and heart failure by more than 50%.

23.3 EVALUATION

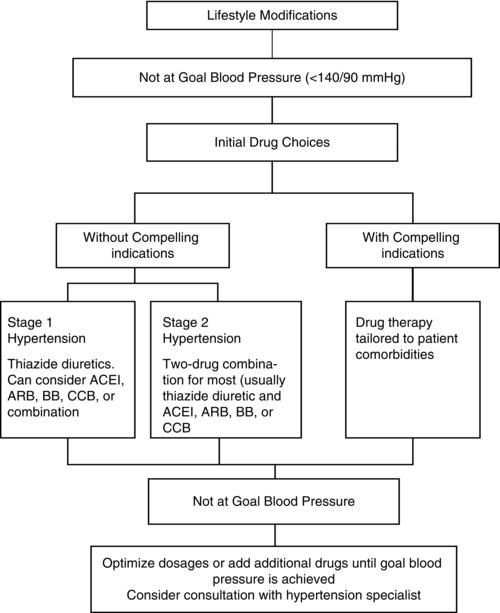

High blood pressure management can be broadly divided into three components (Figure 23.1): identification; diagnostic work-up (including risk factor assessment and secondary cause evaluation); and treatment. Although the identification of patients with high blood pressure has been a national objective for years, most patients with elevated blood pressures are unaware of their condition. Additionally, much of the existing literature on hypertension is focused on therapeutics; as the incidence and prevalence continue to grow, much research is needed to evaluate resource allocation and management strategies. As patient demographics and risk factors change, appropriate management strategies that consider not just efficacy but compliance and comorbidities are crucial components to better optimizing the care for patients with hypertension.

Table 23.1 Classification and Management of Blood Pressure for Adults*.

23.4 DIAGNOSIS

Hypertension is defined as a blood pressure of 140/90 mmHg or higher and is typically diagnosed in the outpatient clinics, in the patient’s home using ambulatory blood pressure monitoring (ABPM), or through patient self-assessment. Typical ambulatory monitors are programmed to take readings every 15 to 30 minutes throughout the day and night without disruption of the patient’s daily activities. In a clinic setting, blood pressure readings can be recorded using standard electronic units or manually using blood pressure cuffs. Care should be taken to ensure that the patient is comfortable, typically resting for five minutes prior to measurement. Several studies suggest that ABPM is more closely correlated with target organ damage (left ventricular hypertrophy and renal dysfunction) compared to traditional office measurements. Classification of hypertension category should be based on an average of two or more blood pressure readings.

Almost 33% of patients with increased blood pressure in the office may have normal pressure at home. One can assume that if daytime blood pressures out of the office are below 130/80 and there is no evidence of end organ disease due to hypertension, the patient has “white coat” hypertension secondary to the adrenergic surge of being in a physician’s office.

23.5 WORKUP

The diagnostic strategy for patients with documented hypertension includes a workup for other typical cardiovascular risk factors (Table 23.2), identifiable causes of hypertension (Table 23.3), and to evaluate systems for evidence of end-organ damage (Table 23.4). Specifically, the physical examination should include confirmation of elevated BPs in the contralateral arm, fundoscopic examination, calculation of body mass index (BMI), auscultation of heart and lungs with a focus on signs suggestive of vascular abnormalities (bruits, abdominal masses, and peripheral pulses), and neurologic assessment. Standard laboratory tests obtained before initiation of antihypertensive therapies include: electrocardiogram (ECG); urinalysis; basic metabolic profile; lipid panel; thyroid stimulating hormone; and blood glucose. More extensive laboratory tests are generally not indicated unless a secondary cause of hypertension is suspected or the patient is resistant to pharmacotherapies.

If the diagnosis of hypertension is first being made in patients under the age of 20 or greater than 60 or resistant to medical therapy, secondary causes of hypertension should be sought more aggressively. Resistant hypertension is defined as blood pressure that remains above goal despite the use of three or more different classes of antihypertensive agents. Primary aldosteronism should be considered in those with hypertension and any of the following characteristics: (1) unexplained hypokalemia; (2) hypokalemia secondary to diuretics but not responding to treatment; (3) family history of mineralcorticoid excess; (4) highly resistant hypertension; or (5) adrenal mass noted on imaging study. A diagnosis of primary aldosteronism can obtained with a plasma aldosterone level >15 ng/dl in the setting of a low renin level. Renovascular hypertension can occur as a result of secondarily elevated renin levels in the presence of renal artery stenosis. A diagnosis can be confirmed by renal angiogram (Figure 23.2), ultrasound and magnetic resonance arteriography imaging studies. Finally, pheochromocytomas are catecholamine-producing tumors that result in hypertension and nonspecific symptoms such as palpitations, diaphoresis, headaches, and anxiety. Additionally, many common medications can interfere with blood pressure control, mimicking resistant hypertension. Some common examples include NSAIDS, decongestants, stimulants, alcohol, oral contraceptives, and herbal compounds such as ephedra.

Table 23.2 Cardiovascular Risk Factors.

| Hypertension |

| Cigarette smoking |

| Obesity (BMI > 30 kg/m2) |

| Physicial inactivity |

| Dyslipidemia |

| Diabetes mellitus |

| Age (older than 55 for men, 65 for women) |