Demographics

Age. Venous disease is typically a disease of an aging population. VTE occurs both in the young and in the old, although there is an agedependent increase (30- to 40-fold higher incidence in 80-year-old compared to 30-year-old persons). It is estimated that VTE risk doubles with each decade of age. VTE in the young is almost always a consequence of a thrombotic diathesis. The incidence of varicose veins and CVI sequelae also increases with age, and age independently predicts the development of these complications.

Gender. The overall incidence of VTE in women and men is quite similar. However, men appear to have increased risk for VTE recurrence compared to women. Women have a three-fold to four-fold higher risk for varicose veins than men. Despite the strong link between varicosities and the eventual development of CVI, sequelae of CVI paradoxically tend to be more common in men than in women.

Race. The risk for VTE show racial differences, with whites at greater risk than Hispanics. Asians have the lowest risk for VTE. This may be due to differences in genetic factors that predispose to DVT.

Obesity. Obesity increases the risk for varicosities in women but not in men. Obesity is an independent predictor of development of CVI. Whether obesity increases the risk of VTE is debated. If obesity results in significant immobility, indeed the risk may increase.

History of Present Illness

While many patients with venous disease are asymptomatic, pain, swelling, and skin changes are the most common signs and symptoms of acute or chronic venous disease. Patients may present with any combination of these symptoms. The variability in presentation can be fairly remarkable. Some patients may present for the evaluation of asymptomatic skin abnormalities such as a telangiectasia, while at the other end of the spectrum, patients may present with fulminant manifestations of CVI including edema, hyperpigmentation, lipodermatosclerosis, and venous ulceration.

A careful history should be focused on defining the onset, progression, and exacerbating and relieving factors, and associated clinical signs and symptoms for the clinical complaint (

Table 19.2). It may be helpful to know what diagnostic studies have been performed and whether the symptoms are improving or worsening with time. The history, examination, differential diagnosis, and testing will also be affected by unilateral vs. bilateral symptoms. The history should include cataloging whether the patient has had a recent surgical procedure, prolonged travel, immobility, history

of cancer, trauma, medications, or illnesses that may predispose to acute VTE. A careful assessment of risk factors for DVT may be helpful in identifying factors that may have played a role.

Table 19.1 lists various risk factors including surgical procedures and risk for developing a DVT.

Prolonged immobility increases the risk of DVT. Hospitalization, air travel (greater than 8 hours), or long car trips are included in this assessment. The increase with air travel appears to be modest, and this does not appear to translate into an increase in the incidence of PE in the general population. Trauma is strongly associated with DVT, with more than 50% of individuals with trauma to the lower extremities and more than 40% of those with trauma elsewhere (chest and abdomen) demonstrating evidence of DVT with duplex evaluation. A history of

fracture of the long bones of the lower extremity or the pelvic bones increases the risk of asymptomatic DVT. The use of indwelling devices such as central venous catheters, pacemakers, and infusion ports is strongly associated with the development of DVT at the site of insertion.

Pain Associated with Venous Disease. The majority of patients with DVTs are asymptomatic. Pain may however occur in the context of any acute or chronic venous disorder. In superficial thrombophlebitis and DVT, the

clinical findings (see physical examination) that accompany the pain may suggest the need for further evaluation and intervention. Typically, the pain is of new or abrupt onset and associated with new or acute swelling, warmth, or erythema of the limb. In addition, the patient may report a cordlike structure that is painful, tender, and/or red. Individuals with extensive DVT (iliofemoral disease) may often experience a bursting discomfort in the lower extremities on exertion (venous claudication) that is relieved slowly with rest and elevation (see venous claudication in

Table 19.2).

The pain of CVI is typically described as an ache toward the end of the day felt in the entire lower extremity or in a portion of the limb. This is also true in the setting of PTS. In acute exacerbations of CVI, including stasis dermatitis, patients may have fairly acute onset of symptoms; thus, imaging to exclude DVT is sometimes warranted. Pain is not a typical complaint in varicosities, and the presence of pain over a varix should raise the suspicion of associated thrombophlebitis. It is common for patients with varicosities to experience atypical symptoms such as pricking, tingling, prurutis, or burning discomfort over the site. Restless leg syndrome is an underappreciated disorder that can complicate both varicose veins and CVI.

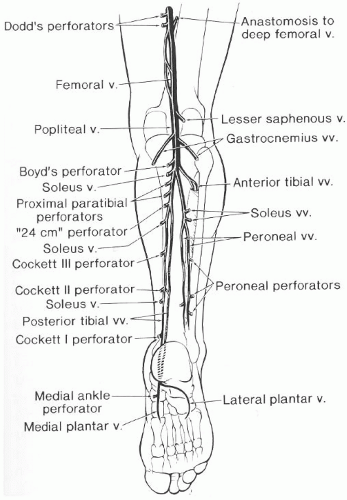

Swelling. This is the second most common manifestation of venous disease and is a manifestation of venous hypertension. Venous hypertension is the pathophysiologic hallmark of CVI. Venous hypertension represents transmission of venous pressure to the deep and superficial veins. Obstruction and/or reflux aided by gravity and incompetent valves increases pressure within the deep and communicating veins. Other causes for venous hypertension that should be considered include (i) intrinsic venous thrombosis, (ii) extrinsic venous compression such as May-Thurner syndrome or Cockett’s syndrome where the left iliac vein is compressed by the overlying right common iliac artery, and (iii) elevated right heart pressure due to various causes. The location, onset, duration, and aggravating or relieving factors for swelling should be carefully considered.

Table 19.2 provides differentiating features of venous edema from other causes of lower extremity swelling.

Past Medical and Surgical History

A history of DVT makes recurrent DVT a strong consideration in a patient presenting with other suggestive signs and symptoms. Similarly, a history of DVT makes PTS and CVI a more likely cause of the lower extremity swelling. The risk of VTE is increased by concomitant associated influences (see

Table 19.1). A personal or family history of venous thromboembolism, spontaneous abortion, or pregnancy morbidity should increase concern for an inherited or acquired form of thrombophilia.

A history of

malignancy or

myeloproliferative syndrome is associated with a higher incidence of DVT. In addition, DVT could be the first manifestation of a malignancy in 3 to 20% of individuals. Carcinoma of the lung is the most common tumor associated with a DVT by virtue of its higher

prevalence compared to other malignancies. Gastrointestinal (pancreas and stomach)- and genitourinary-associated carcinomas and adenocarcinomas of unknown primary are more strongly linked to development of thrombosis.

Paralysis due to spinal cord injury is also associated with an increased risk for VTE including PE. The risk of DVT after paralysis is greatest during the first 2 weeks after injury; deaths resulting from PE are relatively rare after 3 months.

Pregnancy increases the risk of VTE with the highest risk in the immediate postpartum period (20 times higher than control nonpregnant women).

Inflammatory bowel disease has also been associated with increased risk for DVT.

Medication History

Estrogen, hormone replacement, OCPs, and selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs) increase the risk for DVT. Newer OCPs have a significantly lower amount of estrogen than prescribed decades ago but nonetheless still increase risk of DVT. In addition, OCPs with third-generation progestins have increased risk for VTE compared to OCPs containing second-generation progestins. Still, a woman’s risk of VTE-related death from estrogen-based contraceptive therapy is lower than her risk of dying from pregnancy. The risk (hazard ratio) for a postmenopausal woman on hormone replacement therapy developing a DVT is approximately 2.1 (based on HERS and the Women’s Health Initiative studies). Combining hormonal therapy with other VTE triggers magnifies the VTE risk. For example, oral contraceptive use may be at increased risk for DVT or cerebral thrombosis. However, in individuals with inherited thrombophilia, OCP use dramatically increases the risk. In patients with the prothrombin 20210 mutation risk increases up to 120-fold and with Factor V Leiden mutation risk is increased 30- to 40-fold.

In cancer patients, the introduction of chemotherapy or radiation therapy may increase the risk for VTE. The use of medications such as hydralazine, procainamide, and phenothiazines should be considered since they are known to potentially induce antiphospholipid antibodies. Exposure to heparin or low-molecular-weight heparin predisposes patients to formation of heparin-induced platelet factor 4 antibodies and heparin-induced thrombocytosis that may increase the risk for VTE.