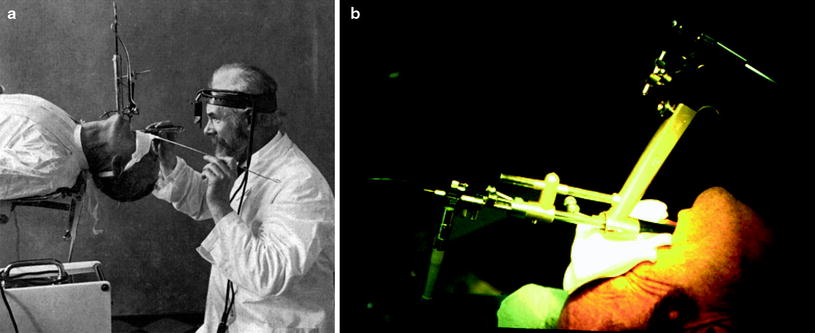

Fig. 1.1

Gustav Killian performing bronchoscopy. He is holding the bronchoscope with his left hand, while guiding a suction catheter with the right hand. His coworker is pumping the balloon for suctioning secretions, while the nurse is attending the patient, who is lying on his left side and has to tolerate the procedure under local anesthesia. (a) On the right is an illustration of the bronchoscope, modified by Killian’s coworker Brünings. On the proximal end of the bronchoscope is a spring with a serrated edge, to which another tube could be attached and forwarded as far as necessary. Attached to the handle is Hacker’s electroscope for illumination and onto that a telescope is mounted for enlarging the image (b)

In order to fully understand the importance of endoscopic removal of foreign bodies, one has to consider the state of thoracic surgery at Killian’s time. Most of the patients fell chronically ill after the aspiration of a foreign body, suffering from atelectasis, chronic pneumonia, and hemorrhage from which half of them died if left untreated. Surgical procedures were restricted to “pneumotomy” when the bronchus was occluded by extensive solid scar tissue, and the foreign body could not be reached by the bronchoscope, which had a very high mortality rate. Lobectomy or pneumonectomy could not be performed before Brunn and Lilienthal developed the surgical techniques after 1910, and Nissen, Cameron Haight, and Graham introduced pneumonectomy after 1930, because techniques of safe closure of the bronchial stump were missing.

Thus for those who were confronted with these patients it must have seemed like a miracle that already briefly after the introduction of bronchoscopy almost all patients could be cured. According to statistical analysis by Killian’s coworker Albrecht, of 703 patients with aspiration of foreign bodies during the years 1911–1921, in all but 12 the foreign body could be removed bronchoscopically, although many had remained inside the airways for a considerable time, a success rate of 98.3%. In light of these results Killian’s triumphant remarks become understandable when he writes: “ One has to be witness, when a patient who feels himself doomed to death can be saved by the simple procedure of introducing a tube with the help of a little cocaine. One must have had the experience of seeing a child that at 4 pm aspirated a little stone, and that, after the stone has been bronchoscopically removed at 6 pm, may happily return home at 8 pm after anesthesia has faded away. Even if bronchoscopy was ten times more difficult as it really is, we would have to perform it just for having these results.”

Besides numerous instruments for foreign body extraction other devices, such as a dilator and even the first endobronchial stent, were constructed. Although further development of bronchoscopy was Killian’s main interest, in the years at Freiburg he promoted treatment in other fields too. He developed a method for submucosal resection of the septum of the nose and a new technique for radical surgery of chronic empyemata of the sinuses with resection of the orbital roof and cover by an osseous flap. Around 1906, he began intensive studies of the anatomy and the function of the esophageal orifice and found the lower part of the m. cricopharyngeus to be the anatomical substrate of the upper esophageal sphincter. According to his observations it was between this lower horizontal part and the oblique upper part of the muscle that Zenkers pulsion diverticulum developed, where the muscular layer was thinnest. One of his scholars, Seiffert, later developed a method of endoscopic dissection of the membrane formed by the posterior wall of the diverticulum and the anterior wall of the esophagus.

In 1907, he received an invitation by the American Oto-Rhino-Laryngological Society to visit the United States, and it was on his triumphant journey through the United States on July 3, 1907, he gave a lecture on his findings at the meeting of the German Medical Society of New York, which was also published in Laryngoscope in the same year. Lectures were followed by practical demonstrations of his bronchoscopic and surgical techniques and by banquets at night. On his journey he also visited Washington, where he had a brief encounter with President Theodore Roosevelt. At Pittsburgh he met Chevalier Jackson, then already the outstanding pioneer of esophago-broncholgy at the University of Pennsylvania. Killian was awarded the first honorary membership of the Society of American Oto-Rhino-Laryngology and also became honorary member of the American Medical Association and received a medal in commemoration of his visit.

As Killian was the most famous laryngologist of Germany, when Fraenkel in Berlin retired in 1911 he became successor to the most important chair of rhino-laryngology. Although bronchoscopy seemed to have reached its peak, he felt that visualization of the larynx was unsatisfactory. When using Kirstein’s spatula for drawing illustrations of pathological findings in corpses, once accidentally the head of a body slipped off the table. This was when Killian realized that inspection of the larynx in a hanging position of the head was much easier. He had a special laryngoscope constructed that could be fixed to a supporting construction by a hook, a technique he called “suspension-laryngoscopy,” by which he could use both hands for manipulation (Fig. 1.2). His pupil Seiffert improved the method by using a chest rest, a technique that later was brought to its perfection by Kleinsasser and is still used for endolaryngeal microsurgery.

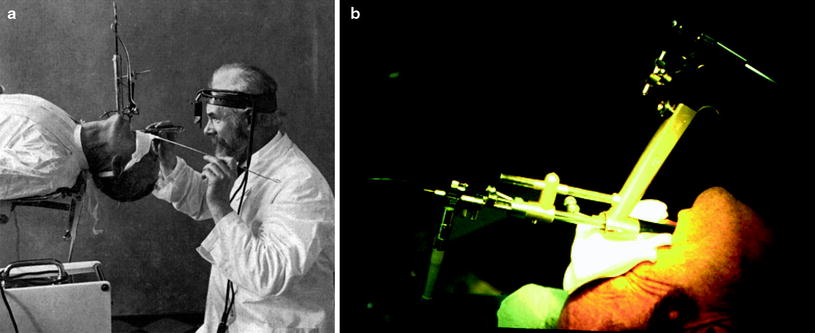

Fig. 1.2

Gustav Killian demonstrating suspension laryngo-bronchoscopy. The patient’s head is suspended on a spatula that is fixed to a metal arm at the table. Illumination is provided by an electric head light, connected to the light source in the foreground by cable. Both hands are free for instrumentation. (a) Kleinsasser’s support laryngoscope is a modern successor that is widely used by today’s ENT surgeons. It rests on the chest of the patient or on a table. Microscopic telescopes and instruments for manipulation can be fixed directly to the device for delicate surgery on the vocal chords (b)

In 1911, Killian had been nominated Professor at the Kaiser-Wilhelm-Military-Academy of Medicine and as during World War I he had to treat many laryngeal injuries he visited the front line in France where he also met his two sons who were doing their military service. After his return he founded a center for the treatment of injuries of the larynx and the trachea. During this era he was very much concerned with plastic reconstruction of these organs, especially as he could refer to the work of Dieffenbach and Lexer, two of the most outstanding plastic surgeons at their times who had also worked at Berlin. The article on the injuries of the larynx should be his last scientific work before he died of gastric cancer in 1921.

During his last years, Killian prepared several publications on the history of laryngo-tracheo-bronchoscopy. For teaching purposes, already in 1893, he began illustrating his lectures by direct epidiascopic projection of the endoscopic image above the patient’s head. Phantoms of the nose, the larynx, and the tracheobronchial tree were constructed according to his suggestions. According to his always cheerful mood he was called the “semper ridens” (always smiling), and in his later years, his head being framed by a tuft of white hair, his nick name was “Santa Claus.” He created a school of laryngologists, and his pupils dominated the field of German laryngology and bronchology for years. Albrecht and Brünings published their textbook of direct endoscopy of the airways and esophagus in 1915. Like von Eicken at Erlangen and Berlin and Seiffert at Heidelberg they had become heads of the most important chairs of oto-rhino-laryngology in Germany. It was to his merit that the separate disciplines of rhino-laryngology and otology were combined. When Killian died on February 24, 1921, his ideas had spread around the world. Everywhere skilled endoscopists developed new techniques, and bronchoscopy became a standard procedure in diagnosis and treatment of the airways. His work was the basis for the new discipline of anesthesiology as well, providing the idea and instruments (laryngoscope by Macintosh) for the access to the airways, endotracheal intubation, and anesthesia.

Throughout all his professional life Gustav Killian kept on improving and inventing new instruments and looking for new applications. He applied fluoroscopy, which had been detected by K. Roentgen in Würzburg in 1895, for probing peripheral lesions and foreign bodies. To establish the X-ray anatomy of the segmental bronchi he introduced bismuth powder. He drained pulmonary abscesses and instilled drugs for clearance via the bronchial route and he even used the bronchoscope for “pleuroscopy” (thoracoscopy) and transthoracic “pneumoscopy,” when abscesses had drained externally. Foreign bodies that had been in place for a long time and had been imbedded by extensive granulations were successfully extracted after treatment of the stenosis by a metallic dilator and in case of restenosis metallic or rubber tubes were introduced as stents. Although cancer was comparatively rare (31 primary and 135 secondary cancers disease in 11,000 postmortems), he pointed out the importance of pre- and postoperative bronchoscopy. Already in 1914, he described endoluminal radiotherapy in cancer of the larynx by mesothorium, and in the textbook of his coworkers Albrecht und Brünings published in 1915, we find the first description of successful curation of a tracheal carcinoma after endoluminal brachy-radiotherapy. Taking special interest in teaching his students and assistants to maintain high standards in quality management by constantly analyzing the results of their work and always keeping in mind that he himself was standing on the shoulders of excellent pioneers, he kept up the tradition of the most excellent in his profession like Billroth of Vienna. In his inaugural lecture in Berlin on November 2, 1911, he pointed out that it was internal medicine from which the art of medicine had spread to the other faculties and that patience and empathy should be the main features of a physician, but on the other hand to persist in following your dreams because “to live means to be a fighter”. He ignited the flame of enthusiasm in hundreds of his contemporaries who spread the technique to other specialties thus founding the roots for contemporary interventional procedures like microsurgery of the larynx (Kleinsasser) and intubation anesthesia (Macintosh, Melzer, and Kuhn).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree