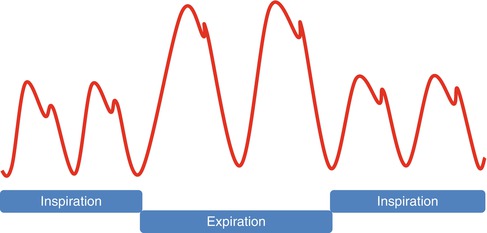

Fig. 3.1

A classic three component friction rub and its timing within the cardiac cycle

Pericardial Effusion Without Compression

Background

Pericardial effusion is an accumulation of fluid in the pericardial space between the visceral and parietal pericardium that is in excess of what is normally present (15–50 mL) [6].

History and Presentation

Pericardial effusions have various etiologies but it is typically suspected based n history and physical exam, supported by an electrocardiogram and chest x-ray and confirmed by an imaging modality such as an echocardiogram. They are often found incidentally on evaluation of suspected cardiopulmonary disease.

Most patients, unless there is cardiac tamponade, characteristically are asymptomatic even with large (≥1 liters), slow developing pericardial effusions [7]. If symptoms do develop, they usually arise from the compression of surrounding structures such as the stomach, lung and phrenic nerve and include dysphagia, nausea, abdominal fullness, dyspnea and orthopnea [6, 9]. Those with fever are often related to the underlying cause such as pericarditis.

Physical Examination

The exam is often unremarkable with a small effusion. However, those with a large effusion can have distant or muffled heart sounds on auscultation. There is also dullness beyond the point of maximal impulse upon percussion in the absence of lung disease to the left lower lobe.

While it is not routinely performed today, the combination of dullness to percussion, bronchial or tubular breath sounds and egophany in a triangular area at the tip of the left scapula is known as the Ewart’s or Bamberger-Pins-Ewart sign described in 1896 [10].

Cardiac Tamponade

Background

Cardiac tamponade is a medical emergency that occurs with the collection of material such as fluid, blood, pus, or clots due to various etiologies such as infection, malignant disease, renal failure, radiation therapy, anticoagulant therapy, invasive cardiac procedures with perforation, cardiovascular surgery, chest trauma and aortic dissection. This leads to increased intrapericardial pressure causing compression of all cardiac chambers and ultimately hemodynamic collapse [9].

History and Presentation

Cardiac tamponade can be the consequence of any etiology of pericardial disease and most symptoms are nonspecific, therefore tamponade is an elusive clinical diagnosis.

The clinical presentation and hemodynamic effect of patients with cardiac tamponade principally depends upon the volume of the effusion, rapidity of accumulation and the clinical circumstances. Acute cardiac tamponade typically occurs within minutes in patients with mechanical complication of the heart or great vessels such as cardiac or aortic rupture, trauma, or complication of an invasive procedure and present with the characteristic Beck’s triad of hypotension, elevated jugular venous pressure (JVP) in addition to dyspnea, tachypnea and chest pain [9]. It is a clinical syndrome in which there is impairment of diastolic filling leading to low cardiac output from the rapid accumulation of fluid in a relatively stiff pericardium that can be life-threatening if not quickly recognized and treated.

In subacute cardiac tamponade, the rate of growth of the pericardial effusion tends to be slower, filling the pericardial space up to 2 liters and allowing pericardial stretch and compensatory mechanisms to take place with a gentler rate of increase in pericardial pressures [6]. Early in their course, patients lack symptoms but as the pericardial reserve volume is met, there is poor organ perfusion causing confusion, cool extremities and worsening renal function. They also develop fatigue, chest pressure, peripheral edema and dyspnea progressing to orthopnea until it reaches the critical point causing life-threatening tamponade [9, 11, 12].

Low-pressure cardiac tamponade is a phenomenon that occurs in patients with severe hypovolemia due to hemorrhage, overdiuresis, or hemodialysis with intracardiac diastolic pressures that are only 6–12 mmHg [9, 13]. Most common symptoms include weakness and dyspnea on exertion.

Large pericardial effusions can lead to atypical presentations by means of localized compression. There can be compression of the phrenic nerve as it traverses the pericardium leading to hiccups, diaphragm causing nausea, esophagus producing dysphagia, and left recurrent laryngeal nerve triggering atypical Ortner’s Syndrome causing hoarseness [7].

Physical Examination

Physical examination is crucial in patients with cardiac tamponade as it is considered a clinical diagnosis.

The combination of the classic Beck’s triad of hypotension, elevated JVP and distant heart sounds is infrequently present (10–40 %) in acute cardiac tamponade. Patients with cardiac tamponade can be hypotensive, normotensive or even hypertensive [9, 14–16]. Hypotension is not universally seen in patients with subacute or low-pressure cardiac tamponade. In fact, hypertension (even over 200 mmHg) with characteristic features of tamponade, while infrequent, is not rare and has been described as a tamponade variant due to excessive sympathetic activation in the setting of subacute cardiac tamponade and is typical in patients with preexisting hypertension [9, 14]. One of the key physical findings is jugular venous distension (JVD) that is almost always present and with clear lungs to distinguish it from left-sided heart failure. While it may be difficult to appreciate, it is important to detect abnormality in the waveforms of the jugular pulsations. In normal patients, jugular pressure falls twice, first during ventricular ejection (x descent) and again during early rapid ventricular filling (y descent). The two descents are parallel with two peaks in venous return. In cardiac tamponade, the x descent is preserved because cardiac size diminishes during ventricular ejection, which is more rapid than cardiac filling allowing the lowering of intrapericardial pressure causing the venous return to peak. However, due to the abnormally elevated intrapericardial constraint from the effusion, there is reduced diastolic compliance leading to the lack of the y descent. The y descent is diminished in mild cases and absent in moderate or severe cases of cardiac tamponade [8, 9]. However, there can be a normal or low JVP in cases of rapidly developing cardiac tamponade, particularly with hemorrhagic cardiac tamponade because of the shortage of time for compensatory increase in venous pressure [8].

Traditionally, most patients (77 %) will exhibit sinus tachycardia (a heart rate of more than 90 beats per minute) to partially maintain cardiac output and tachypnea (80 %) [9, 16, 17]. Furthermore, tachycardia may not be seen in patients with early cardiac tamponade despite evidence of hemodynamically significant effusion. However, exceptions to the rule include those with hypothyroidism and uremia that can be bradycardic [7, 9]. It is also important to note that patients with sudden accumulation of fluid in the pericardial space can also lead to bradycardia due to increased vagal tone. Contrary to common belief, an audible friction rub may be heard especially in patients with inflammatory pericarditis [7].

Pulsus Paradoxus

The hallmark physical examination finding of cardiac tamponade is a paradoxical pulse, which is found in over three-quarters of moderate to severe cardiac tamponade cases [16–18]. Pulsus paradoxus is an inspiratory decline in systolic blood pressure of more than 10 mmHg resulting from two physiologic phenomenons that reduces left ventricular stroke volume on inspiration. First, there is compression and poor filling of the left ventricle caused by increased venous return to the right side of the heart referred to as ventricular interdependence. In addition, inspiratory drop in blood pressure is due to the incomplete transmission of negative intrathoracic pressures to the left side of the heart (left ventricular diastolic pressure) while maintaining this decrease in the pulmonary capillary bed and pulmonary veins, thus decreasing the gradient between the pulmonary veins and the left atrium and the left ventricular diastolic pressure. On physical examination, the pulsus paradoxus can be appreciated as a decreased force of the pulse synchronous with inspiration. In extremely severe cases, the pulse dissipates completely during inspiration. A regular heartbeat but an irregular peripheral pulse is the paradox. Using a sphygmomanometer, it is typically the first audible blood pressure sound during expiration but disappears with inspiration. As the cuff pressure is deflated, blood pressure sounds are audible throughout the respiratory cycle. The difference in pressure between the two sounds allows an estimation of the severity of pulsus paradoxus. Essentially this can be best illustrated, as seen in Fig. 3.2, with an arterial line showing a decreased blood pressure on inspiration. This finding can be difficult to recognize in severe shock in the radial pulse but will still be apparent in the femoral or carotid pulse. Pulsus paradoxus may be absent in cardiac tamponade in patients with chronic hypertension leading to elevated ventricular diastolic pressures, low-pressure tamponade, atrial septal defects or aortic insufficiency [9, 17–19]. This phenomenon can also be seen in extracardiac diseases such as pulmonary embolism and intrinsic lung disease such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and severe asthma. While more commonly associated with severely impaired left ventricular function, there may be the presence of pulsus alternans, a fluctuation of a weak pulse and a strong pulse in the presence of a regular rhythm as seen in Fig. 3.3. This is primarily thought to be due to alteration in end-diastolic pressure that affects the efficiency of the Frank-Starling mechanism.