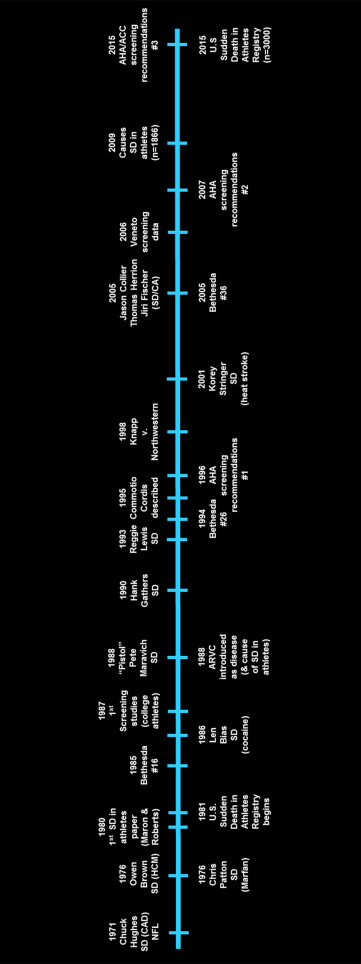

Sudden death in young competitive athletes has become a highly visible and substantial issue within cardiovascular medicine of interest both to the general public and to the practicing community. At this time, it is instructive to revisit the evolution of this clinical problem over the past 35 years starting with introduction into the public and medical consciousness by the unexpected sudden deaths of 2 college basketball players within 8 weeks of each other in 1976, 1 with Marfan syndrome and the other with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Subsequently, over the next years, a number of elite athletes died suddenly, raising public visibility and awareness of these tragic events: Len Bias, “Pistol” Pete Maravich, Hank Gathers, Reggie Lewis, Kori Stringer, Jason Collier, and Thomas Herrion. Intense interest in these and many other athlete deaths has led to a considerable understanding regarding the demographics, incidence, and causes of these deaths, which include a variety of genetic and/or congenital cardiovascular diseases (most commonly hypertrophic cardiomyopathy), blunt trauma, commotio cordis, and sickle cell trait. Ultimately, initiatives emerged creating consensus guidelines for disqualification versus eligibility decisions, and preparticipation screening to detect unsuspected cardiac abnormalities. This journey of now >3 decades has generated voluminous data and even controversy, but continues to hold great interest in clinical scientists, medical practitioners, and the general public.

Sudden collapse and death of a young trained athlete in competition or at practice continues to be a counterintuitive and highly visible public event, given that such individuals are generally regarded as representative of the healthiest segment of society. However, public reaction to these tragic events is perhaps not dissimilar to that many years ago, as evident in the well-regarded 117-year-old poem by Alfred Edward Housman ( Figure 1 ). In recent years, much has been learned about those sudden deaths occurring in healthy young subjects engaged in sports at the high school and college level and beyond and the causes of these tragic events. This report describes how the deaths of competitive athletes have evolved into a public health issue for the general community and practicing physicians, and has become part of contemporary cardiovascular medicine ( Figure 2 ).

Background

Remarkably, 30 to 35 years ago, the sudden deaths of athletes did not achieve widespread public recognition and were instead regarded primarily as private family tragedies. In addition, early on, these deaths were not subjected to scientific inquiry, with virtually no documentation of the medical causes. In fact, prevalent speculations surrounding these athlete deaths focused on a mysterious and undefined “sudden death syndrome” with vague allusions to causative metabolic, environmental, or physical stresses on the circulatory system, as well as incriminating the “careless” and extreme physical workloads that precipitated heart failure in inadequately conditioned subjects. In effect, responsibility for the sudden death of an athlete was assigned largely to the lifestyle of the athlete.

Indeed, reports suggesting cardiovascular abnormalities as the primary cause of these deaths in athletes were virtually absent before 1980. One exception is the 1967 report by Dr. Thomas James of 2 athletes who died suddenly in whom the only potentially relevant abnormality present at autopsy was narrowing of the artery to the sinus node due to medial and intimal hyperplasia (requiring serial sectioning of the conduction system). For a time, this histopathologic finding was considered the cause of sudden deaths of athletes.

The Beginning

In 1971, Chuck Hughes, aged 28 years, a wide receiver for the Detroit Lions with a history of chest pain, became the first and only National Football League player to die during a game ( Figure 3 ). His sudden death was due to premature undiagnosed coronary atherosclerosis with thrombosis, later recognized as a consequence of familial hypercholesterolemia. However, this event did not achieve traction in the lexicon of sudden death in athletes, probably because it occurred during the pre-television era for professional football.

Interest in the cardiovascular diseases causing sudden deaths in athletes did not begin in earnest until several years later. In April 1976, a unique confluence of events was ultimately responsible for focusing attention and ultimately a vast body of literature, surrounding all aspects of sudden death in young athletes ( Figures 2-4 ). Within the highly successful University of Maryland Division I National Collegiate Athletic Association basketball program (College Park, Maryland; Washington, D. C. metropolitan area), 2 athletes died suddenly associated with physical exertion only 2 months apart ( Figures 3 and 4 ).

First, Owen Brown, aged 23 years, collapsed while engaged in an informal basketball game a few months after graduation ( Figure 4 ). At autopsy, the diagnosis and cause of death was hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Previously, arrhythmias had been recognized on routine exercise stress test screening, but the diagnosis remained unresolved after a workup including cardiac catheterization. Although hypertrophic cardiomyopathy has subsequently proved to be the single-most common cardiac cause of sudden deaths in U.S. competitive athletes on the basis of a multitude of autopsies performed over 3 decades, this postmortem diagnosis of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in Owen Brown (by Dr. William C. Roberts) was the first in a competitive athlete.

Second, exactly 8 weeks later, Chris Patton, age 21, died suddenly from a ruptured aorta while playing pickup basketball. Mr. Patton had an unrecognized Marfan syndrome phenotype ( Figure 4 ), and there had been no previous suspicion of cardiac disease that might place him at risk. Therefore, the story of sudden death in young athletes began with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and Marfan syndrome ( Figures 3 and 4 ).

It should also be underscored that these 2 deaths in student-athletes came only shortly after the introduction of echocardiography (M-mode) into clinical practice (1972 to 1973), imaging technology capable of detecting left ventricular hypertrophy or aortic root enlargement. Furthermore, the University of Maryland and Coach “Lefty” Driesell had been early advocates of screening for cardiac disease in this athlete population.

The tragic sudden deaths of 2 athletes from the same college athletic program very close in time was so improbable and counterintuitive that it triggered substantial media interest and even some distrust in the cardiac diagnoses responsible for both of these deaths ( Figure 4 ). In this era of investigative journalism and the Watergate scandal (1972 to 1974), newspaper reporters in the Washington DC area mused about an (imaginary) conspiracy, remarkably (and erroneously) suggesting the possibility that the medical examiner had altered the publicly disclosed causes of death.

In contrast, this media interest promoted public and nationwide reporting of sudden deaths in athletes with the Associated Press routinely placing these events on the news service wire, thereby triggering exposure into the public domain. In turn, this permitted acquisition and assembly of vast amounts of data by sources such as the U.S. National Registry of Sudden Death in Athletes (Minneapolis, Minnesota) that has now tabulated almost 3,000 cases over 35 years and is responsible for a substantial literature describing the epidemiology, causes, and incidence of sudden death events in athletes. Eventually, other large athlete populations have also been studied, including the National Collegiate Athletic Association cohort, Olympic Games competitors, marathon runners, U.S. professional athletes, and recreational (noncompetitive) sports participants.

Ten years after the deaths of Owen Brown and Chris Patton, the sudden death risks of illicit drugs came to the forefront when elite University of Maryland basketball student-athlete Len Bias, aged 22 years, died in 1986 from what appeared to be a cocaine overdose ( Figures 2, 3 and 5 ). The timing of this event was particularly inopportune, coming just 2 days after Mr. Bias, with almost unlimited potential as a professional athlete, became the second overall selection in the 1986 National Basketball Association (NBA) draft. Mr. Bias and other teammates had previously tested negative for drugs in a program initiated by Coach Driesell. The University of Maryland athletic department and coaching staff were criticized publicly and unfairly by the University Chancellor, although there was absolutely no evidence that these parties were in any way responsible or negligent, or could have prevented this tragic event by any reasonable means. Therefore, solely by chance, in 1 decade, 3 athletes from the University of Maryland basketball program tragically died of 3 different causes, underscoring the broad spectrum of the previously underrecognized causes of these events.

The Beginning

In 1971, Chuck Hughes, aged 28 years, a wide receiver for the Detroit Lions with a history of chest pain, became the first and only National Football League player to die during a game ( Figure 3 ). His sudden death was due to premature undiagnosed coronary atherosclerosis with thrombosis, later recognized as a consequence of familial hypercholesterolemia. However, this event did not achieve traction in the lexicon of sudden death in athletes, probably because it occurred during the pre-television era for professional football.

Interest in the cardiovascular diseases causing sudden deaths in athletes did not begin in earnest until several years later. In April 1976, a unique confluence of events was ultimately responsible for focusing attention and ultimately a vast body of literature, surrounding all aspects of sudden death in young athletes ( Figures 2-4 ). Within the highly successful University of Maryland Division I National Collegiate Athletic Association basketball program (College Park, Maryland; Washington, D. C. metropolitan area), 2 athletes died suddenly associated with physical exertion only 2 months apart ( Figures 3 and 4 ).

First, Owen Brown, aged 23 years, collapsed while engaged in an informal basketball game a few months after graduation ( Figure 4 ). At autopsy, the diagnosis and cause of death was hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Previously, arrhythmias had been recognized on routine exercise stress test screening, but the diagnosis remained unresolved after a workup including cardiac catheterization. Although hypertrophic cardiomyopathy has subsequently proved to be the single-most common cardiac cause of sudden deaths in U.S. competitive athletes on the basis of a multitude of autopsies performed over 3 decades, this postmortem diagnosis of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in Owen Brown (by Dr. William C. Roberts) was the first in a competitive athlete.

Second, exactly 8 weeks later, Chris Patton, age 21, died suddenly from a ruptured aorta while playing pickup basketball. Mr. Patton had an unrecognized Marfan syndrome phenotype ( Figure 4 ), and there had been no previous suspicion of cardiac disease that might place him at risk. Therefore, the story of sudden death in young athletes began with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and Marfan syndrome ( Figures 3 and 4 ).

It should also be underscored that these 2 deaths in student-athletes came only shortly after the introduction of echocardiography (M-mode) into clinical practice (1972 to 1973), imaging technology capable of detecting left ventricular hypertrophy or aortic root enlargement. Furthermore, the University of Maryland and Coach “Lefty” Driesell had been early advocates of screening for cardiac disease in this athlete population.

The tragic sudden deaths of 2 athletes from the same college athletic program very close in time was so improbable and counterintuitive that it triggered substantial media interest and even some distrust in the cardiac diagnoses responsible for both of these deaths ( Figure 4 ). In this era of investigative journalism and the Watergate scandal (1972 to 1974), newspaper reporters in the Washington DC area mused about an (imaginary) conspiracy, remarkably (and erroneously) suggesting the possibility that the medical examiner had altered the publicly disclosed causes of death.

In contrast, this media interest promoted public and nationwide reporting of sudden deaths in athletes with the Associated Press routinely placing these events on the news service wire, thereby triggering exposure into the public domain. In turn, this permitted acquisition and assembly of vast amounts of data by sources such as the U.S. National Registry of Sudden Death in Athletes (Minneapolis, Minnesota) that has now tabulated almost 3,000 cases over 35 years and is responsible for a substantial literature describing the epidemiology, causes, and incidence of sudden death events in athletes. Eventually, other large athlete populations have also been studied, including the National Collegiate Athletic Association cohort, Olympic Games competitors, marathon runners, U.S. professional athletes, and recreational (noncompetitive) sports participants.

Ten years after the deaths of Owen Brown and Chris Patton, the sudden death risks of illicit drugs came to the forefront when elite University of Maryland basketball student-athlete Len Bias, aged 22 years, died in 1986 from what appeared to be a cocaine overdose ( Figures 2, 3 and 5 ). The timing of this event was particularly inopportune, coming just 2 days after Mr. Bias, with almost unlimited potential as a professional athlete, became the second overall selection in the 1986 National Basketball Association (NBA) draft. Mr. Bias and other teammates had previously tested negative for drugs in a program initiated by Coach Driesell. The University of Maryland athletic department and coaching staff were criticized publicly and unfairly by the University Chancellor, although there was absolutely no evidence that these parties were in any way responsible or negligent, or could have prevented this tragic event by any reasonable means. Therefore, solely by chance, in 1 decade, 3 athletes from the University of Maryland basketball program tragically died of 3 different causes, underscoring the broad spectrum of the previously underrecognized causes of these events.