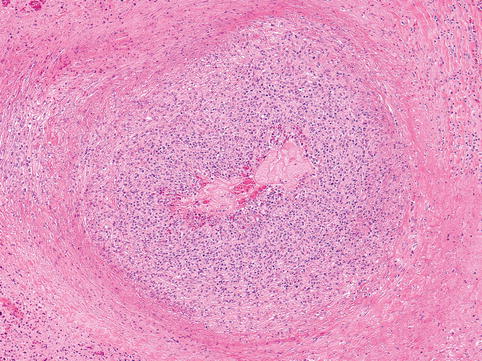

Fig. 21.1

EBV pneumonitis shows dense pulmonary perivascular and interstitial infiltrates

21.8 Lymphomatoid Granulomatosis

Lymphomatoid granulomatosis was first described by Liebow and colleagues in 1972 as an angiocentric and angiodestructive lymphoreticular proliferation (Liebow et al. 1972). The emphasis focused on histologic features of angiitis and granulomatosis, and this disease was not initially considered to be neoplastic. However, with time, lymphomatoid granulomatosis was recognized as a lymphoproliferative disorder and grouped with lethal midline granuloma/polymorphic reticulosis, as an angiocentric immunoproliferative disorder. These diseases shared extranodal involvement, were angiocentric and angioinvasive, showed conspicuous necrosis, and a prominent inflammatory component with many T cells (Lipford et al. 1988). Advances in immunophenotyping and molecular genetic analysis subsequently demonstrated that nearly all of the “angiocentric immunoproliferative disorders” could be classified as one of two distinct entities: (1) extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma, an Epstein-Barr-virus (EBV)-positive lymphoma with a predilection for midfacial localization of NK cell, and less often of T-cell lineage, and (2) lymphomatoid granulomatosis, an EBV-positive B-cell lymphoproliferative disorder with a prominent component of reactive T cells (Guinee et al. 1994; Nicholson et al. 1996). Some observers suggested that lymphomatoid granulomatosis was immunophenotypically diverse and could be of either B- or T-cell lineage, including T-cell cases unassociated with EBV (Myers et al. 1995), but this view has fallen out of favor in preference for a more restricted definition for lymphomatoid granulomatosis. Lymphomatoid granulomatosis is now defined as an angiocentric, angiodestructive lymphoproliferative disease composed of EBV+ B cells with reactive T cells in which T cells usually predominate (Pittaluga et al. 2008). Lymphomatoid granulomatosis may involve a variety of extranodal sites and less often lymph nodes, but pulmonary involvement is by far the most common and characteristic manifestation.

21.9 Clinical Features

Lymphomatoid granulomatosis mainly affects adults, with patients often being middle-aged (Jaffe and Wilson 1997; Katzenstein et al. 1979; Nicholson et al. 1996), although older adults (Katzenstein et al. 1979; Nicholson et al. 1996) and rarely children (Cuadra-Garcia et al. 1999; Katzenstein et al. 1979) are affected. Males contract the disorder at roughly twice as often as females (Katzenstein et al. 1979; Nicholson et al. 1996; Pittaluga et al. 2008). Although the majority of patients who develop lymphomatoid granulomatosis are not overtly immunodeficient, an underlying immunologic abnormality is associated with an increased risk for developing lymphomatoid granulomatosis, as is the case for many EBV+ lymphoproliferative disorders (Cuadra-Garcia et al. 1999; Jaffe and Wilson 1997; Pittaluga et al. 2008). Lymphomatoid granulomatosis has been reported in HIV+ patients (Haque et al. 1998), individuals with autoimmune disease (Kameda et al. 2007; Nicholson et al. 1996), patients with prior or concurrent hematologic malignancies (Cuadra-Garcia et al. 1999; Katzenstein et al. 1979; Muller et al. 2007), allograft recipients (Joseph et al. 2008), and children with certain congenital immunodeficiency syndromes (Pittaluga et al. 2008). Rare cases of lymphomatoid granulomatosis have been described in patients receiving imatinib, a tyrosine kinase inhibitor that can cause severe lymphopenia in the treatment of a gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) (Salmons et al. 2007; Yazdi et al. 2007). Even when there is no obvious immunodeficiency, when immunologic abnormalities are specifically sought, they are frequently found, and these include anergy, lymphopenia, defective cytotoxic T-cell activity, and impaired response to EBV (Jaffe and Wilson 1997; Pittaluga et al. 2008).

Patients present with respiratory symptoms, constitutional symptoms, or both; few are asymptomatic (Katzenstein et al. 1979). Symptoms may include fever, cough, malaise, dyspnea, weight loss, chest pain, and hemoptysis. Some patients present with neurological symptoms related to central or peripheral nervous system involvement or skin lesions related to cutaneous involvement. A few have myalgias, arthralgias, or nonspecific gastrointestinal symptoms (Jaffe and Wilson 1997; Joseph et al. 2008; Katzenstein et al. 1979; Muller et al. 2007; Nicholson et al. 1996; Pittaluga et al. 2008; Salmons et al. 2007; Yazdi et al. 2007).

In nearly all cases (>90 %) there is pulmonary involvement (Katzenstein et al. 1979; Pittaluga et al. 2008). Lung lesions are bilateral in nearly 80 % of cases (Katzenstein et al. 1979), with preferential involvement of mid- and lower lung fields (Pittaluga et al. 2008). Some of those presenting with unilateral lung involvement later develop bilateral lung disease (Katzenstein et al. 1979; Nicholson et al. 1996). Radiographic studies show multiple nodules, often suggesting metastases or consolidation (Joseph et al. 2008; Katzenstein et al. 1979; Muller et al. 2007; Nicholson et al. 1996). Lobar collapse and diffuse reticulonodular infiltrates are also described (Katzenstein et al. 1979; Nicholson et al. 1996).

21.10 Pathology

On gross examination, the lung lesions are gray-white nodules, 1–5 cm in diameter (Haque et al. 1998). Large nodules frequently show ischemic necrosis (Pittaluga et al. 2008). On microscopic examination, the lesions are composed of a variable admixture of small lymphocytes, intermediate-sized lymphoid cells, histiocytes, plasma cells, and atypical lymphoid cells with the appearance of immunoblasts, plasmacytoid immunoblasts, and/or large bizarre cells occasionally reminiscent of Reed-Sternberg cells (Fig. 21.2). The process is characterized by angiocentric and angiodestructive growth. Although histiocytes may be numerous, and despite the name of the disease, well-formed granulomas are not a feature. Eosinophils and neutrophils are inconspicuous (Haque et al. 1998; Jaffe and Wilson 1997; Joseph et al. 2008; Katzenstein et al. 1979; Pittaluga et al. 2008). Establishing a diagnosis may require excision of one or more nodules rather than needle biopsy because viable, diagnostic areas may be present only focally.