Outline the various causes of hemoptysis and discuss the pathogenesis and pathophysiology in relation to the source of bleeding.

Outline the various causes of hemoptysis and discuss the pathogenesis and pathophysiology in relation to the source of bleeding.

Develop an algorithm for the diagnosis and management of hemoptysis and illustrate with clinical examples.

Develop an algorithm for the diagnosis and management of hemoptysis and illustrate with clinical examples.

GENERAL CONSIDERATIONS

Hemoptysis means coughing of blood and must not be confused with hematemesis or vomiting of blood. The incidence of hemoptysis varies widely and depends on the clinical setting. The duration of hemoptysis and the characteristics of expectorated blood may provide clues to its cause. The quantity of expectorated blood may range from blood-streaked sputum to a life-threatening amount. Although the designation is arbitrary, hemoptysis of 300 mL in 24 hours has been termed massive and could be life threatening because of the risk of aspiration, airway compromise, or associated hemodynamic collapse. Although fewer than 5% of all cases of hemoptysis are massive, mortality rates can be as high as 60%–75% in this group. Airway compromise may be life threatening even if hemoptysis is not massive in quantity. The unpredictability of recurrent hemoptysis, its poor correlation to parenchymal bleeding, and the absence of specific accurate predictors of outcome hinder its management. The rate of bleeding, associated ventilatory and hemodynamic derangements, and underlying comorbid conditions are major factors associated with poor outcomes in patients with hemoptysis.

ETIOLOGY

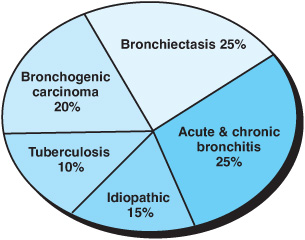

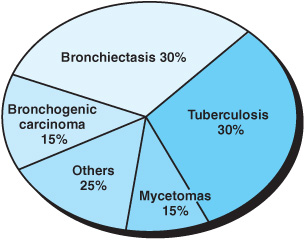

Worldwide, tuberculosis (TB) and bronchiectasis remain the most common causes of hemoptysis; other major causes are outlined in Figures 3–1 and 3–2. Although this list has essentially remained the same over the past 40 years, the rank order of the detectable causes in this list has changed due to the introduction of newer diagnostic techniques. The pathogenesis of bleeding and its pathophysiologic derangement depends on the underlying process (Table 3–1) and is described in the following section. About 90% of the bleeding originates from bronchial circulation and its collaterals such as the axillary and intercostal vessels. The pulmonary circulation accounts for about 10% of all sources of hemoptysis. Various pathologic entities can be characterized by the predominant bleeding site and the structural defects associated with them (Table 3–2). The pathophysiology and pathogenesis of some of these clinical entities are discussed in the following sections.

Figure 3–1. Some common causes of mild to moderate hemoptysis seen in an out-patient clinic setting.

Figure 3–2. Some common causes of moderate to severe hemoptysis requiring in patient hospital observation.

PATHOGENESIS

Bronchiectasis

Bronchiectasis results from the destruction of the cartilaginous support of the bronchial wall by inflammation, infection, or alveolar fibrosis and traction.

Table 3–1. Classification of primary diseases in the differential diagnosis of hemoptysis

Pulmonary |

Airways disease: bronchitis, bronchiectasis, broncholith, adenoma, endobronchial hamartoma |

Infections: pneumonia, lung abscess, tuberculosis, fungal disease |

Vascular: pulmonary embolism, arteriovenous malformations |

Cardiovascular |

Congestive heart failure, mitral valvular disease |

Others |

Vasculitides |

latrogenic/traumatic |

Bleeding disorders/use of anticoagulants |

Substance abuse/drugs |

Table 3–2. Etiology of hemoptysis: site and predominant circulation involved

Endobronchial site |

Chronic bronchitis |

Foreign body/broncholith |

Endobronchial mass/lesion |

Bronchial circulation |

Bronchiectasis |

Chronic bronchitis |

Tuberculosis |

Mycetoma |

Pulmonary venous hypertension |

Bronchogenic carcinoma |

Pulmonary circulation |

Cavitary tuberculosis |

Arteriovenous malformations |

Lung abscess |

Broncholiths |

Peripheral lung masses/carcinoma |

Radiation |

latrogenic |

Diffuse capillary |

Diffuse alveolar damage |

Diffuse alveolar hemorrhage |

ldiopathic alveolar hemorrhage |

Autoimmune disorders/vasculitides |

Capillaritis |

Acellular fibrotic strands replace small airways causing traction. This is accompanied by muscular hypertrophy, bronchomalacia, and architectural distortion. Most patients with massive hemoptysis have severe underlying necrotic, destructive, and fibrotic lung changes. Chronic purulent endobronchial infection also leads to suppurative tissue necrosis and generation of granulation tissue in the peribronchial region with bronchiectasis. The accompanying bronchial vessels undergo hypertrophy, with expansion of the submucosal vascular plexus and formation of bronchopulmonary anastomoses. The peripheral vessels are inflamed and this results in intense neovascularization and rupture of vessels which may initiate the onset of hemoptysis. A rich secondary vascular supply with anastomotic channels and increased pulmonary hypertension contributes to recurrent hemoptysis in these cases.

Tuberculosis

Intrapulmonary bleeding in TB may be multifactorial with attendant bronchiectasis depending on its acuity and site. Bleeding in TB may be due to necrosis of a small pulmonary artery or may result from rupture of vessels that run through or are tangential to the cavities resulting from chronic infection. At autopsy these patients have localized rupture of a dilated portion of the pulmonary artery traversing thick-walled cavities. These vessels are thought to be innocent bystanders caught up in the rim of inflammation and organization. Transient increases in pulmonary artery pressure may cause vascular rupture in a cavity. Tuberculous involvement of the vessel wall with local inflammation causes aneurysmal dilatation. The outer vessel is affected first, and the process of tissue destruction and replacement with granulation tissue progresses toward the lumen, leaving a weakened wall which bulges into an aneurysm called a Rasmussen aneurysm. As classically described, rupture of this aneurysm is a well-known albeit uncommon cause of massive hemoptysis.

Bronchogenic Carcinoma

About 7% of patients with bronchogenic cancer present with hemoptysis, and 20% have hemoptysis during the course of their illness. Squamous cell carcinoma is associated with an increased incidence of massive hemoptysis compared to other tumor types. However, there is no statistical correlation between cell types and frequency of hemoptysis. Massive bleeding is usually rare and mostly due to tumor erosion of large pulmonary vessels. Tumor necrosis and vascular rupture more commonly occur and cause small amounts of recurrent bleeding. Direct invasion of the pulmonary vasculature by tumor cells is rare. Metastatic disease in the lung from malignancies such as breast, kidney, colon, and esophageal cancer may extend directly into the tracheobronchial tree, resulting in hemoptysis. Endobronchial adenomas can bleed due to their vascular polypoid stalk and extend into the submucosa with their rich bronchial artery supply and cause hemoptysis because of their rich fibrovascular stroma and marked hypervascularity.

Chronic Bronchitis

Hemoptysis in chronic bronchitis arises from the superficial vessels in the bronchial mucosa. The bronchial arteries are increased in size and tortuosity in this condition. Increases in pulmonary artery pressure secondary to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and development of precapillary bronchopulmonary anastomoses may further aggravate the condition, leading to recurrent hemoptysis.

Pulmonary Mycetoma

Mycetomas occur in patients with preexisting cavitary or bullous lung disease resulting from old granulomatous disease such as TB or sarcoidosis. A mycetoma is a saprophytic fungal infection with necrotic cellular debris, mucus strands, and fibrin. Aspergillus species or mucormycosis may cause such a “fungus ball.” Hemoptysis is a common symptom in mycetomas, but the pathogenesis is not clear. Although it has been speculated that hemolytic endotoxin, proteolytic enzymes, and microinvasion of fungus into the cavity wall may contribute to bleeding in pulmonary mycetoma, autopsy studies suggest that the bleeding may actually be due to friction of the fungus ball against the cavity wall. Pathologically, ulceration of cavitary lining, severe inflammation, increased number and congestion of capillaries, and fibrosis and thrombosis of bronchial and pulmonary arteries are seen. Abrasion of such capillaries with friction against the wall is the most likely cause of hemoptysis in these cases. Any change in position or change in the intrathoracic pressure can increase this movement and friction, thereby increasing the chance of bleeding.

Invasive Fungal Disease

Hemoptysis can also occur in invasive pulmonary fungal infection. In immune-compromised patients, bleeding and necrosis typically occur after the peripheral neutrophil blood count recovers, resulting in greater tissue inflammation and destruction. Pulmonary microangioinvasion by mycelial elements, which destroys parenchymal and vascular structures, causes infarction and hemorrhage. Fungal invasion of the pulmonary vasculature also results in thrombosis and distal ischemic necrosis and hemorrhage. Aspergillus and zygomycosis are the two major fungal groups causing this condition. In immunocompetent patients, endemic fungi may invade the lung, produce acute and chronic infection mimicking TB, and may cause hemoptysis. Fibrosing mediastinitis due to fungal infection, especially histoplasmosis, may cause hemoptysis by local destruction, fibrosis, vessel rupture, or related secondary pulmonary hypertension.

Broncholithiasis

Hemoptysis due to a broncholith is generally mild and considered benign because of its self-limiting nature. A broncholith is a calcified mediastinal lymph node(s) most commonly due to an infectious etiology. Histoplasmosis is the most frequent underlying cause of broncholithiasis in the United States. Other causes include TB, other fungal infections, actinomycosis, nocardiosis, and silicosis. Over time these calcified lymph nodes lead to external compression or erosion of the adjacent airways and vascular structures, causing obstruction and hemoptysis. A few cases of massive hemoptysis due to broncholithiasis have been described as a late complication resulting from erosion of broncholiths into the lung parenchyma, causing rupture of a pulmonary or bronchial artery, or from an aortotracheal fistula. Although there is no surrounding inflammation or bronchial artery collaterals, the broncholith is in close proximity to pulmonary veins. Healed, calcified peribronchial nodes may impinge on the bronchial lumen and erode vessels, resulting in pressure necrosis with fistula formation and hemoptysis.

Lung Abscess & Necrotizing Pneumonia

Lung abscess can cause hemoptysis when a necrotic cavity spreads directly into a surrounding vascularized lung. A large abscess may erode major pulmonary vessels resulting in massive hemoptysis. Formation of pseudoaneurysms or secondary filling of the abscess cavity will lead to recurrent hemoptysis. Pneumonia, especially with gram-negative bacteria and necrotizing infection, can lead to tissue breakdown and resultant alveolar damage and hemoptysis.

Cardiovascular Causes

Primary or secondary pulmonary hypertension from any congenital heart disease, such as Eisenmenger’s complex, can result in hemoptysis. The long-standing state of high flow or pressure in the pulmonary artery circulation may lead to rupture of atheromatous plaques. In mitral stenosis, the primary site of bleeding is the bronchial veins; this bleeding is caused by increased capillary blood flow and pulmonary venous hypertension. Elevated left atrial pressure is transmitted back through the pulmonary veins to the capillaries, causing retrograde flow through the bronchopulmonary anastomoses, dilating the bronchial venous plexus. Blood is directed back to the right heart via azygos and intercostal veins. These prominent varices then may rupture in the presence of infection or increased intravascular volume or pressure.

Pulmonary Embolism

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree