Chapter 8

Heart muscle diseases

Classification

Heart muscle diseases include a diverse range of cardiomyopathies and myocardites. Cardiomyopathies have been previously classified as diseases of unknown cause and were therefore distinct from more specific causes of heart muscle disease such as ischaemia, hypertension, and valvular heart disease. However, a better understanding of their aetiology and pathophysiology has led to this distinction becoming obsolete.

Definition

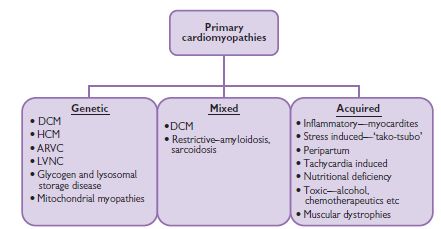

Cardiomyopathies can be defined as a heterogeneous group of diseases of the myocardium, characterized by mechanical and/or electrical dysfunction that typically (though not invariably) exhibit inappropriate ventricular hypertrophy or dilatation and are due to a variety of causes that are frequently genetic. Cardiomyopathies are either confined to the heart or are part of generalized systemic disorders, often leading to cardiovascular death or progressive heart failure-related disability (Fig. 8.1).1

Fig. 8.1 Primary cardiomyopathies can be divided into genetic and acquired causes of heart muscle disease.1 DCM = dilated cardiomyopathy; HCM = hypertrophic cardiomyopathy; ARVC = arrhythmogenic right ventricular myopathy; LVNC = left ventricular non-compaction.

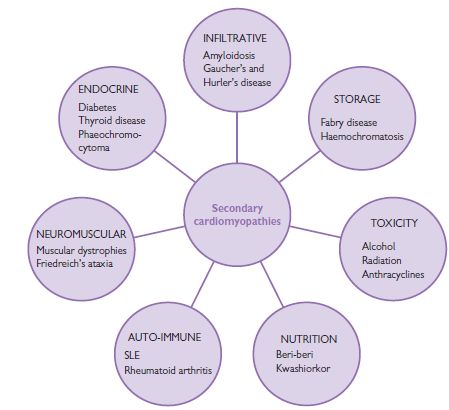

Cardiomyopathies can be classified according to the predominant organ involvement. Primary cardiomyopathies are those confined to the heart muscle and can be further subdivided into genetic and acquired forms. Secondary cardiomyopathies occur as part of a variety of generalized systemic diseases, often with multi-organ involvement, which also demonstrate myocardial pathology.

Primary cardiomyopathies

Primary cardiomyopathies are predominantly confined to the heart only. They can be further classified into genetic and acquired groups, though overlap exists with certain forms of cardiomyopathy, in particular dilated cardiomyopathy.

Secondary cardiomyopathies

Secondary cardiomyopathies are typically part of generalized multisystem diseases. Cardiac manifestations may be an isolated feature, though multiple organ involvement is more common. Conversely, if no evidence of myocardial disease is found, regular surveillance for cardiac involvement with history, examination and non-invasive investigations is important. Fig. 8.2 lists examples of conditions associated with secondary cardiomyopathy but is not exhaustive.

Fig. 8.2 Secondary cardiomyopathies can be a feature of many generalized systemic diseases.

Dilated cardiomyopathy

Dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) is characterized by cardiac chamber enlargement and impaired systolic dysfunction, although diastolic dysfunction is almost always also present. The prevalence is 5–8 per 100 000 and it is 3 times more frequent in black and male than white and female individuals.

Symptoms

Clinical presentation may be abrupt, with acute pulmonary oedema, systemic or pulmonary emboli, or even sudden death, but more often patients present with progressive symptoms of congestive cardiac failure (CCF) including exertional dyspnoea, orthopnoea, paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnoea, and fatigue. Right upper quadrant discomfort, nausea, and anorexia may relate to hepatic congestion. Syncope is an ominous symptom and should be regarded to represent a potentially fatal arrhythmia unless subsequent investigation indicates otherwise.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is established by physical examination, electrocardiography, chest X-ray (CXR), and echocardiography.

Aetiology of dilated cardiomyopathy

Although originally considered to be idiopathic, experimental and clinical data now suggest that genetic, viral, and autoimmune factors play a role in its pathophysiology. Several genetic mutations have been identified as the causative problem in familial DCM, while certain viruses have been shown to cause sporadic cases of DCM. The following list is not exhaustive and there is some overlap with specific cardiomyopathies.

DCM is essentially a diagnosis of exclusion, and potentially reversible causes including coronary artery disease, valvular heart disease, and adult congenital heart disease should be sought. Careful attention should also be paid to dietary history and alcohol consumption, as some reversibility is possible with modification of these factors.

Additional investigations for DCM—the ‘cardiomyopathy screen’

Dilated cardiomyopathy: treatment

Management of DCM focuses on relieving symptoms and improving prognosis and quality of life. Pulmonary and peripheral congestion are effectively treated with diuretics. Prognostically important pharmaceutical therapies inhibit the maladaptive neurohormonal process involving the sympathetic system and rein–angiotensin–aldosterone axis. The acute management of heart failure is discussed in Chapter 7, p.367.

Diuretics

Loop diuretics, are useful in relieving symptoms caused by pulmonary and peripheral congestion. Careful monitoring of electrolytes is important, as intravascular depletion may cause urea to rise, and hypokalaemia is common. Hypokalaemia may be counteracted by the co-administration of a potassium-sparing diuretic such as amiloride or spironolactone. Spironolactone is an aldosterone antagonist. The recent RALES (Randomized Aldactone Evaluation Study) trial (see p. 106) demonstrated that the use of low-dose spironolactone can reduce mortality in patients with severe CCF.

Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors

There is overwhelming scientific evidence that angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACE-Is) improve symptoms and outcomes in patients with heart failure, irrespective of symptoms. First-dose hypotension used to be a concern but this is rarely observed with newer ACE-Is and usually only in patients who are relatively intravascularly depleted due to the concomitant use of high-dose diuretics. Side-effects include a dry cough, which may affect up to 20% of patients and is due to increased levels of bradykinin. Angioedema is a rare but potentially life-threatening complication of ACE-Is. Angiotensin receptor 1 antagonists (ARBs) can be used as an alternative in patients who experience a dry cough.

Contra-indications to ACE-I include established bilateral renovascular disease, severe aortic stenosis, pregnancy, and a baseline potassium >6 mmol/L. ACE-Is should be prescribed with caution in individuals with a resting systolic blood pressure <90 mm Hg or basline creatinine >200 µmol/L.

Beta-blockers

Beta-blockers also provide symptomatic and prognostic benefit and are recommended in all patients with dilated cardiomyopathy unless there are specific contraindications. Beta-blockers are effective through several mechanisms, which include a reduction of myocardial oxygen consumption, enhanced LV filling, inhibition of the apoptotic effects of catecholamines on cardiac myocytes, treatment of cardiac arrhythmias, and upregulation of beta-1 receptors. Given the potentially negative inotropic effects, the drugs are initiated in low doses, which are titrated up gradually. They should not be started in patients with overt heart failure.

Aldosterone antagonists

Alodosterone antagonists improve symptoms and prognosis and are recommended in patients who continue to remain in NYHA (New York Heart Association) class III despite adequate doses of ACE-Is and beta-blockers. The most important complication is hyperkalaemia due to the concomitant use of ACE-I. Painful gynaecomastia is a recognized side-effect, particularly in males taking digoxin and anti-androgens.

Antiarrhythmic agents

Antiarrhythmics agents have not been shown to reduce the incidence of sudden cardiac death (SCD) in patients with DCM. AF is a common arrhythmia in DCM and may be associated with symptoms of cardiac decompensation. Most individuals are rate controlled with β-blockers, although digoxin may be used as additive treatment in individuals who continue to exhibit rapid heart rates despite satisfactory doses of β-blocker. Maintenance of sinus rhythm is usually unsuccessful in the long term.

Anticoagulation

Patients with DCM are prone to thromboembolic complications and should be anticoagulated with warfarin regardless of underlying rhythm.

Device therapy

Cardiac transplantation

Orthotopic cardiac transplantation using an allograft can be considered in patients who are severely symptomatic despite maximal medical therapy. The limited availability of donor organs still restricts its role. As a result, there is considerable interest in using organs from other species (xenografts). However, technical hurdles still remain before this can be considered a viable option. The artificial heart is another area that has received much interest and publicity, and clinical trials are soon to be conducted.

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) is characterized by unexplained LVH and has a prevalence of 1 in 500. HCM is a heterogeneous disorder in terms of clinical manifestation, cardiac morphology, and natural history. Whereas the vast majority of affected individuals have a relatively normal life span, HCM is most recognized for being the commonest cause of exercise-related SCD in young individuals under 35 years of age.

Genetics

HCM exhibits marked allelic and non-allelic heterogeneity, with multiple mutations in at least 12 genes encoding sarcomeric contractile protein. The majority of the mutations (>70%) are in the β-myosin heavy chain, troponin T and myosin-binding protein C genes (see Table 8.1).

Table 8.1 The frequency of sarcomeric gene mutations in HCM

| Mutation | Frequency (%) |

| β-myosin heavy chain | 40 |

| Myosin-binding protein C | 25 |

| Troponin I | <10 |

| Troponin T | <5 |

| α-Tropomyosin | <5 |

| Myosin light chain | <1 |

| α-Myosin heavy chain | <1 |

| Titin | <0.5 |

| Actin | <0.5 |

Pathophysiology

The macroscopic hallmark of HCM is LVH, which usually affects the interventricular septum in an asymmetric fashion; however, almost any pattern of LVH is possible, including concentric LVH as seen in individuals with hypertension, and hypertrophy localized to only 1 or 2 myocardial segments. The magnitude of LVH is also variable and can range from very severe LVH (>30 mm) to very mild LVH (13–15 mm). There are also recognized familial cases where the only manifestation of the disorder is an abnormal ECG. Individuals with HCM often exhibit elongated mitral valve leaflets. Histologically, there is evidence of myocyte disarray, myocardial scarring, and abnormal intramyocardial arterioles. Together, these abnormalities manifest as:

LVOT obstruction occurs as a consequence of forward motion of the anterior mitral leaflet towards the hypertrophied proximal interventricular septum in systole. There are two main postulated mechanisms, which include (1) anterior displacement of the papillary muscles and (2) the so-called Venturi effect, created by rapid ejection of blood across a narrow LVOT, which ‘sucks’ the anterior mitral valve leaflet against the septum. See also Table 8.2.

Table 8.2 Dynamic manoeuvres to assess LVOT obstruction

| Decreased LVOT obstruction (murmur softer and shorter) | Increased LVOT obstruction (murmur louder and longer) |

| ↑LV volume | ↓LV volume |

| Squatting | Sudden standing |

| Handgrip | Valsalva (during) |

| Passive leg elevation | Sublingual glyceryl trinitrate (GTN) |

| Valsalva (after release) | Hypovolaemia |

| Mueller manoeuvre (deep inspiration against a closed glottis) | Dehydration |

| ↓Contractility | ↑Contractility |

| Beta-blockers (acute IV) | Beta-agonists (e.g. isoprenaline) |

| ↑Afterload | ↓Contractility |

| Phenylephrine | α-Blockade |

| Handgrip |

Symptoms

Patients with HCM are often asymptomatic and often identified incidentally during routine medical examination, an abnormality on the ECG, or through family screening following the diagnosis in a first-degree relative.

Recognized symptoms may include:

Physical examination

Look for LVH (a forceful apical impulse and an S4 heart sound). Outflow tract obstruction is evident by a double apical impulse and ejection systolic murmur beginning in mid-systole, which may be augmented by provocation by manoeuvres such as Valsalva or squatting. A pansystolic murmur due to mitral regurgitation resulting from the SAM of the mitral valve may also be present.

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: investigations

ECG

Echocardiography

Echocardiography continues to remain the gold standard investigation due to its widespread availability. The investigation is usually for detection of the presence, magnitude, and distribution of LVH, as well as identifying patients with basal LVOT obstruction. Recognized echocardiographic features include:

Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

Cardiac MRI is extremely helpful for identifying apical HCM, evaluating the anterolateral free wall, and demonstrating evidence of myocardial scarring and fibrosis.

Other investigations

Other investigations may help in risk stratification, although no single investigation accurately predicts those at risk of SCD, and negative tests do not entirely exclude the risk of SCD:

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: treatment

Approximately half of sudden deaths in HCM occur during or shortly after strenuous exercise, and therefore patients should be advised against competitive sports of a high-dynamic and high-intensity nature. The management of HCM includes (1) amelioration of symptoms including abolition of LVOT obstruction; (2) treatment of arrhythmias; (3) identification of individuals at risk of SCD, with a view to implantation of ICD; and (4) screening first-degree relatives for the disorder.

Treatment for symptoms

β-blockers

β-blockers are the mainstay of therapy for angina, dyspnoea, giddiness, and syncope. They reduce myocardial oxygen demand and improve diastolic filling, and are effective in the treatment of angina and exertional dyspnoea. Large doses may be required.

Calcium-channel antagonists

Calcium-channel antagonists (verapamil and diltiazem) are as effective as β-blockers and may be used in patients in whom β-blockers are not tolerated or are contraindicated.

Management of arrhythmias

Beta-blockers and amiodarone are the anti-arrhythmic agents of choice in the management of supraventricular arrhytyhmias. None of these agents have been shown to reduce the risk of SCD. AV re-entrant tachycardia and atrial flutter are usually amenable to radiofrequency ablation. Sustained VT is treated with amiodarone but such patients are candidates for ICD; the amiodarone reduces the frequency of non-sustained ventricular tachycardia (NSVT) and the need for recurrent anti-tachycardia pacing. Patients with AF should be anticoagulated with warfarin.

Abolition of left ventricular outflow obstruction

Left ventricular outflow obstruction is treated pharmacologically, surgically, or by alcohol-induced trancoronary septal ablation.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree