Heart failure

Introduction

Definition

Heart failure is a complex clinical syndrome in which the heart fails to meet the metabolic demands of the body. It can result from any structural or functional cardiac disorder that impairs the ability of the ventricle to fill with or eject blood. A diagnosis of heart failure is based on the presence of a triad of typical symptoms (shortness of breath on exertion and at rest, fatigue), signs (tachycardia, tachypnoea, raised jugular venous pressure, peripheral oedema, and pulmonary congestion), and objective evidence of a structural or functional cardiac abnormality (cardiomegaly, abnormal echocardiogram, raised natriuretic peptide concentration). A clinical response to treatment directed at heart failure alone (e.g. diuretic use) may be a useful adjunct but is not sufficient to establish the diagnosis.

Epidemiology and prognosis

Heart failure is the fastest-growing cardiovascular disease, affecting 2–3% of the overall population. The prevalence rises with age, affecting between 10% and 20% of the population aged over 70 years. Although recent epidemiological studies indicate improved survival, the overall prognosis remains poor, with mortality exceeding 50% at 5 years. The primary causes of death are either progressive pump failure or sudden cardiac death secondary to ventricular arrhythmia. Morbidity also remains poor, with a high rate of rehospitalization (up to 50% in a year), placing a significant burden on national healthcare systems.

Pathophysiology

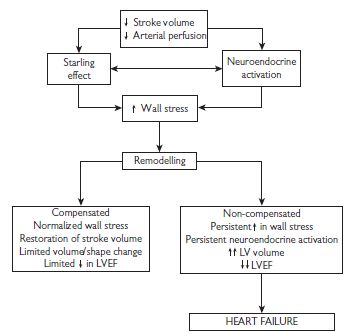

The origin of symptoms in heart failure is poorly understood. An initial event (infarction, inflammation, pressure/volume overload) causes myocardial damage, resulting in an increase in myocardial wall stress. This is followed by the activation of multiple neuroendocrine systems including the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system, the sympathetic nervous system, and the release of cytokines such as tumour necrosis factor (TNF). Neuroendocrine activation is also accompanied by structural and metabolic changes in the peripheral skeletal muscle and by abnormalities in cardiopulmonary reflex function such as the baroreflex and chemoreflex. These produce further wall stress, perpetuating this vicious cycle (see Fig. 7.1).

Fig. 7.1 Pathophysiology of heart failure. LV = left ventricle; LVEF = left ventricular ejection fraction.

Forms of heart failure

Acute vs. chronic heart failure

The clinical manifestations depend on the speed with which the syndrome develops. Acute heart failure is often used to describe the patient with acute-onset dyspnoea and pulmonary oedema, but can also apply to cardiogenic shock where the patient is hypotensive and oliguric. Compensatory mechanisms have not yet become operative. Acute deterioration may be a consequence of myocardial infarction (MI), arrhythmia, or acute valve dysfunction (e.g. endocarditis). See Acute pulmonary oedema: assessment, p. 724.

Systolic vs. diastolic heart failure

Most patients with heart failure have evidence of both systolic (failure of the ventricle to eject blood) and diastolic (failure of the ventricle to relax and fill with blood) dysfunction. Patients with diastolic heart failure have symptoms and signs of heart failure with a preserved LVEF. Current studies indicate that more than 50% of heart failure patients have a normal or near-normal ejection fraction (EF), and their prognosis appears to be similar to that of those with systolic heart failure. The terms diastolic heart failure, heart failure with normal ejection fraction (HFNEF), and heart failure with preserved ejection fraction are used interchangeably.

Right vs. left heart failure

Right and left heart failure refers to whether the patient has either pre-dominantly systemic venous congestion (swollen ankles, hepatomegaly) or pulmonary venous congestion (pulmonary oedema). These terms do not necessarily indicate which ventricle is most seriously affected.

Fluid retention in heart failure is due to a combination of factors: reduced glomerular filtration rate (GFR), and activation of the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system, and sympathetic system. However, remember there are causes for swollen ankles other than heart failure (gravitational disorder, e.g. immobility, venous thrombosis or obstruction, varicose veins, hypoproteinaemia, e.g. nephrotic syndrome or liver disease, lymphatic obstruction).

High-output vs. low-output heart failure

A variety of high-output states may lead to heart failure, e.g. thyrotoxicosis, Paget’s disease, beri-beri, and anaemia. This is characterized by warm extremities and normal or widened pulse pressure. The arterial–mixed venous oxygen saturation (a marker of the ability of the heart to deliver oxygen to the metabolizing tissues) is typically normal or even low in high-output heart failure. In contrast, low-output states are characterized by cool pale extremities, cyanosis due to systemic vasoconstriction, and low pulse volume. The arterial–mixed venous oxygen saturation is typically abnormally high in low-output states.

Causes and precipitants

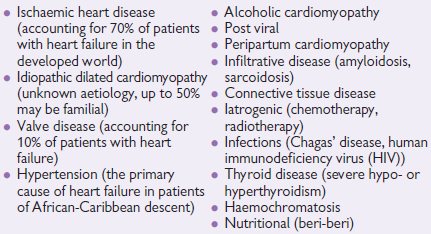

In all patients with heart failure, it is important to carefully consider the underlying aetiology, as there may be specific exacerbating factors or other diseases that influence the patients’ management. A non-exhaustive list is given below.

Aetiology of heart failure

Patients with compensated heart failure have a high rate of readmission to hospital with acute exacerbations. A number of studies have demonstrated that a precipitating cause for emergency admission to hospital with heart failure can be identified in up to two-thirds of patients.

It is very important to look for precipitating causes in all patients with heart failure. Once the precipitant has been identified and treated, appropriate measures (patient and family/education, adjustment of therapy, etc) should be put into place to prevent recurrence. See Table 7.1.

Table 7.1 Population-attributable risk of heart failure related to various risk factorsa

| Risk factor | Attributable risk (%) |

| Coronary disease | 61.6 |

| Cigarette smoking | 17.1 |

| Hypertension | 10.1 |

| Physical inactivity | 9.2 |

| Male sex | 8.9 |

| <High school education | 8.9 |

| Overweight | 80 |

| Diabetes | 3.1 |

| Valvular heart disease | 2.2 |

a He, J, Ogden LG, Bazzano LA, et al (2001). Risk factors for congestive heart failure in US men and women: NHANES 1 Epidemiologic follow-up study. Arch Intern Med 161: 996.

Conditions mimicking heart failure

• Obesity • Chest disease—including lung, diaphragm, or chest wall • Venous insufficiency in lower limbs. • Drug-induced ankle swelling (e.g. dihydropyridine calcium blockers) • Drug-induced fluid retention (e.g. NSAIDs) • Hypoalbuminaemia | • Intrinsic renal disease • Intrinsic hepatic disease • Pulmonary embolic disease • Depression and/or anxiety disorders • Severe anaemia • Thyroid disease • Bilateral renal artery stenosis |

Signs and symptoms

The evaluation of a heart failure patient should start with a comprehensive history and clinical examination. Primary symptoms can be attributed to either reduced cardiac output or fluid accumulation, and include:

• fatigue • dyspnoea (on exertion or at rest) • orthopnoea • paroxysmal noctural dyspnoea • peripheral oedema • chest pain | • palpitations (tachycardia) • hypotension • raised jugular venous pressure (JVP) • displaced apex beat • gallop rhythm (3rd heart sound) • cahexia. |

It is important to remember that heart failure is a multisystem disorder affecting every single aspect of a patient’s body. It is not unusual for patients to present with:

Many of these signs can be difficult to elicit particularly in a noisy emergency or outpatient clinic. Even in study conditions, the reproducibility and inter-observer agreement of the presence of signs is low. Despite this, a clinical diagnosis of heart failure can be made with some certainty when multiple signs are present in the same patient (see Table 7.2).

Symptoms alone can be used to classify the severity of congestive heart failure (CHF) and to monitor the effect of treatment, although the link between symptoms and degree of LV dysfunction is weak. The New York Heart Association classification (NYHA) is widely used.

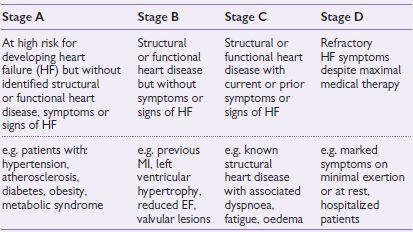

Table 7.2 ACC/AHA stages of heart failure

NYHA classification of heart failure

| Class I | No limitation of physical activity. |

| Class II | Slight limitation of physical activity—symptoms with ordinary levels of exertion (e.g. walking up stairs). |

| Class III | Marked limitation of physical activity—symptoms with minimal levels of exertion (e.g. dressing). |

| Class IV | Symptoms at rest. |

An alternative classification system of heart failure is the ‘Stages of Heart Failure’ proposed by the American College of Cardiology (ACC) and the American Heart Association (AHA). This classification system places particular emphasis on the progressive nature of the heart failure, and defines the appropriate therapeutic approach for each stage (see Table 7.2). Unlike the NYHA classification, this system is unidirectional and therefore cannot be used as a means of assessing the patient’s response to treatment. See also Fig. 7.2.

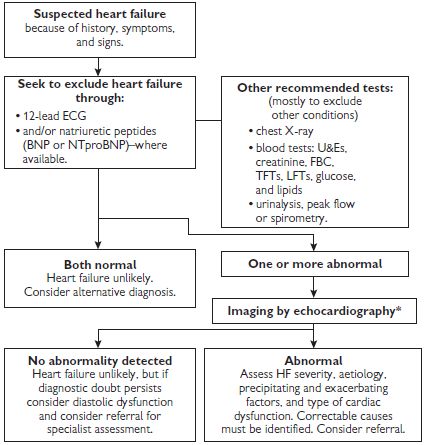

Fig. 7.2 Algorithm summarizing recommendations for the diagnosis of heart failure.

*Alternative methods of imaging the heart should be considered when a poor image is produced by transthoracic Doppler 2D-echocardiography—alternatives include transoesophageal echocardiography (TOE), radionuclide imaging, or cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

BNP = B-type natriuretic peptide; ECG = electrocardiogram; FBC = full blood count; LFTs = liver function tests; NTproBNP = N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide; TFTs = thyroid function tests; U&Es = urea and electrolytes.

Investigations

Investigations for all patients with heart failure

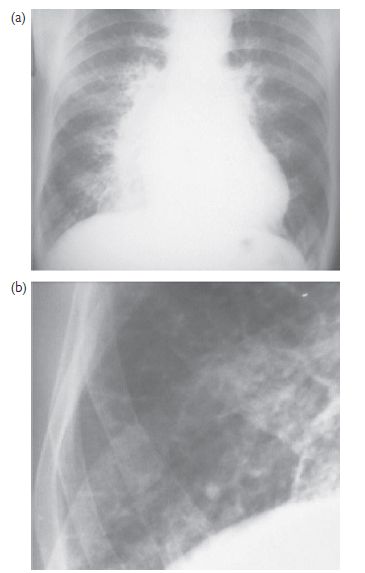

Fig. 7.3 CXR findings in heart failure. (a) There is cardiomegaly with prominent upper lobe vessels and alveolar oedema (‘Bat’s wing shadowing’); (b) magnification of the right costophrenic angle showing septal lines (Kerley B lines) due to interstitial oedema.

Table 7.3 Conditions predisposing to or complicating heart failure that may be identified by echocardiography

| Echocardiographic findings | Examples of possible aetiology |

| Identification of anatomical defects | Atrial septal defect (ASD), ventricular septal defect (VSD) |

| Valvular pathology | Aortic valve or mitral valve stenosis or insufficiency |

| Pericardial disease | Acute or chronic pericarditis Constrictive pericarditis Pericardial effusion |

| Identification of regional ventricular wall motion abnormalities | Ischaemic heart disease |

| Altered myocardial architecture | Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy Infiltrative diseases (amyloidosis) |

| Estimation of pulmonary artery pressure | Pulmonary hypertension (cor pulmonale as a result of primary pulmonary hypertension or secondary to lung disease) |

| Identifying complications of reduced ventricular function | Intramural thrombus secondary to ventricular dilatation, reduced contraction, or aneurysm |

Investigations to consider for selected patients with heart failure

Management of heart failure

Management outline in chronic heart failure

Table 7.4 Essential topics in patient education with associated skills and appropriate self-care behaviours

| Educational topics | Skills and self-care behaviours |

| Definition and aetiology of heart failure | Understand the cause of heart failure and why symptoms occur |

| Symptoms and signs of heart failure | Monitor and recognize signs and symptoms Record daily weight and recognize rapid weight gain Know how and when to notify healthcare provider Use flexible diuretic therapy if appropriate |

| Pharmacological treatment | Understand indications, dosing, and effects of drugs Recognize the common side-effects of each drug |

| Risk-factor modification | Understand the importance of smoking cessation Monitor blood pressure if hypertensive Maintain good glucose control if patient has diabetes Avoid obesity |

| Diet recommendation | Sodium restriction if prescribed Avoid excessive fluid intake Modest intake of alcohol Monitor and prevent malnutrition |

| Exercise recommendation | Be reassured, comfortable about physical activity Understand the benefits of exercise Perform exercise training regularly |

| Sexual activity | Discuss problems with healthcare professionals Be reassured about engaging in sexual intercourse and understand specific sexual problems and various coping strategies |

| Immunization | Receive immunization against infections such as influenza and pneumococcal disease |

| Sleep and breathing disorders | Recognize preventive behaviour such as reducing weight in obese, smoking cessation, abstinence from alcohol Learn about treatment options if appropriate |

| Adherence | Understand the importance of following treatment recommendations Maintain motivation to follow treatment plan |

| Psychosocial aspects | Understand that depressive symptoms and cognitive dysfunction are common in patients with HF, and the importance of social support Learn about treatment options if appropriate |

| Prognosis | Understand important prognostic factors and make realistic decisions Seek psychosocial support if appropriate |

ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure (2008). Eur Heart J 29: 2388–2442.

Objectives of treatment

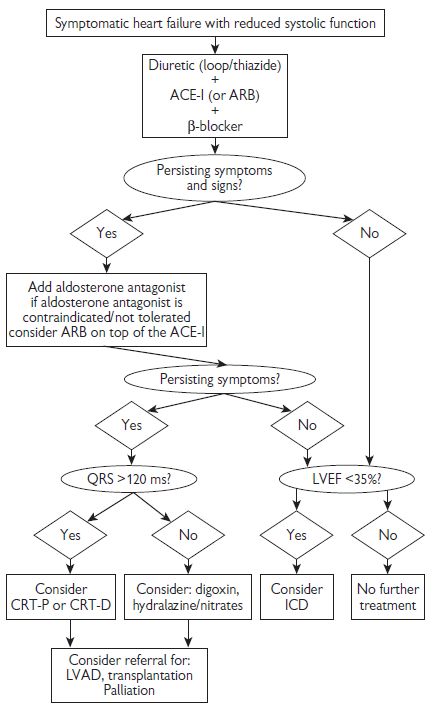

Fig 7.4 summarizes a treatment algorithm for patients with symptomatic HF and reduced systolic function.

Fig. 7.4 Treatment algorithm for patients with symptomatic heart failure and reduced systolic function. Adapted from ESC (2008). Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. Eur Heart J 29: 2388–2442 and NICE guidelines  www.nice.org. ARB = angiotensin receptor blocker; LVAD = left ventricular assist device.

www.nice.org. ARB = angiotensin receptor blocker; LVAD = left ventricular assist device.

Diuretics in heart failure

Practical considerations in the treatment of heart failure with loop diuretics

See Table 7.5.

Table 7.5 Considerations in the treatment of heart failure with loop diuretics

| Problems | Suggested action |

| Hypokalaemia/ hypomagnesaemia | • Increase ACE-I/ARB dosage • Add aldosterone antagonist • Potassium supplements • Magnesium supplements |

| Hyponatraemia | • Fluid restriction • Stop thiazide diuretic or switch to loop diuretic • Reduce dose/stop loop diuretics if possible • Consider arginine vasopressin (AVP) antagonist if available • Intravenous (IV) inotropic support • Consider ultrafiltration |

| Hyperuricaemia/ Gout | • Consider allopurinol • For symptomatic gout use colchicine for pain relief • Avoid NSAIDs |

| Hypovolaemia/ dehydration | • Assess volume status • Consider reduction of diuretic dosage |

| Insufficient response or diuretic resistance | • Check compliance, fluid and salt intake • Review other drugs (NSAIDs, steroids) • Increase dose of diuretic • Consider switching from furosemide to bumetanide or torasemide • Add aldosterone antagonist • Combine loop diuretic and thiazide/metolazone • Administer loop diuretic twice daily or on empty stomach • Consider short-term IV infusion of loop diuretic • Consider low-dose dopamine infusion |

| Renal failure (excessive rise in urea and/or creatinine) | • Check for hypovolaemia/dehydration • Exclude use of other nephrotoxic agents, e.g. NSAIDs, trimethoprim • Withhold aldosterone antagonist • If using concomitant loop and thiazide diuretic stop thiazide diuretic • Consider reducing dose of ACE-I/ARB • Consider ultrafiltration

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

|