H-L

Heart failure

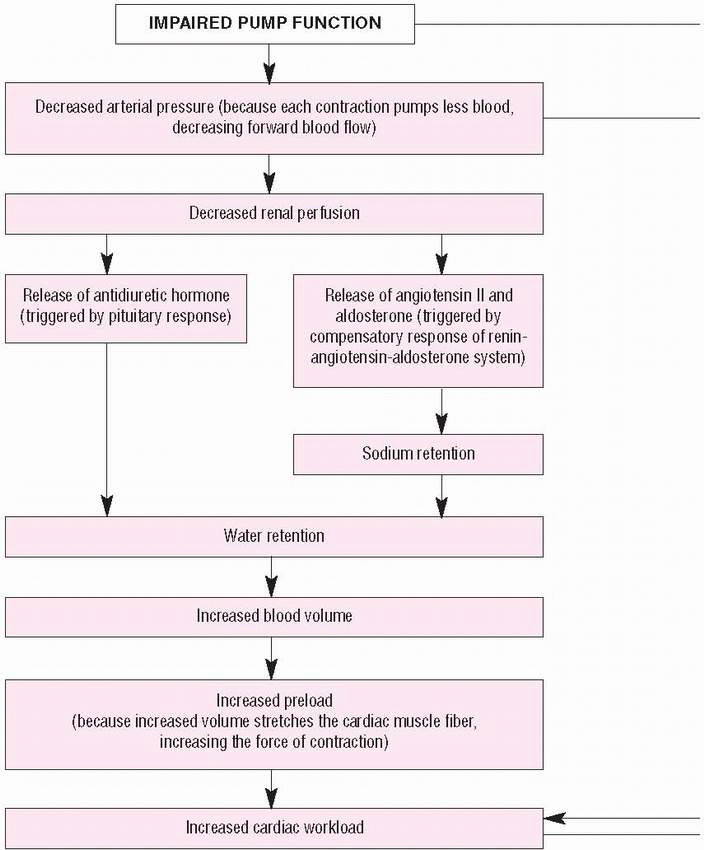

Heart failure is a term used to describe the heart’s inability to pump enough blood to the body’s tissues. This inability typically results from a complex set of interlinked causes and effects in which impaired pump performance (diminished cardiac output) leads to abnormal circulatory congestion.

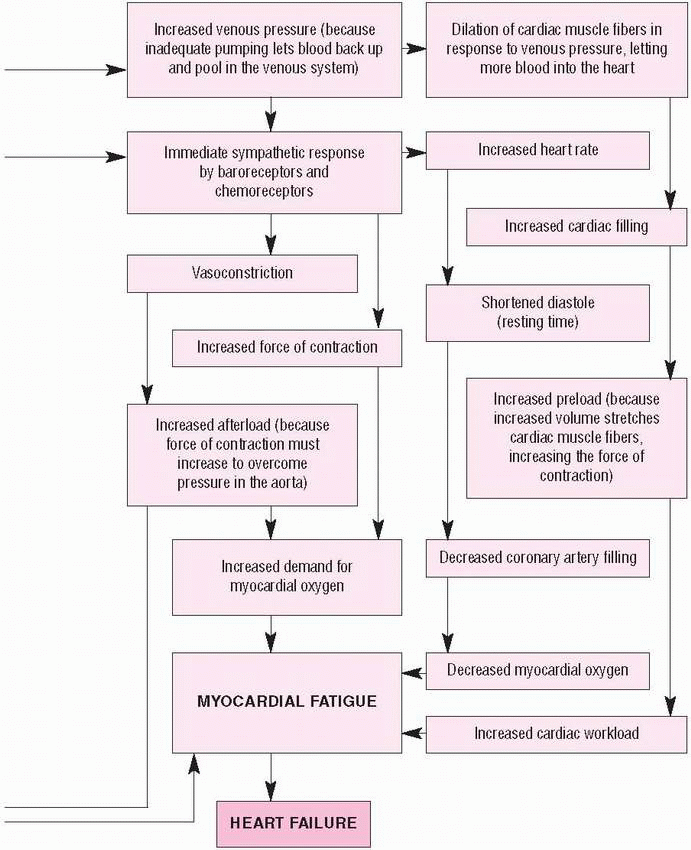

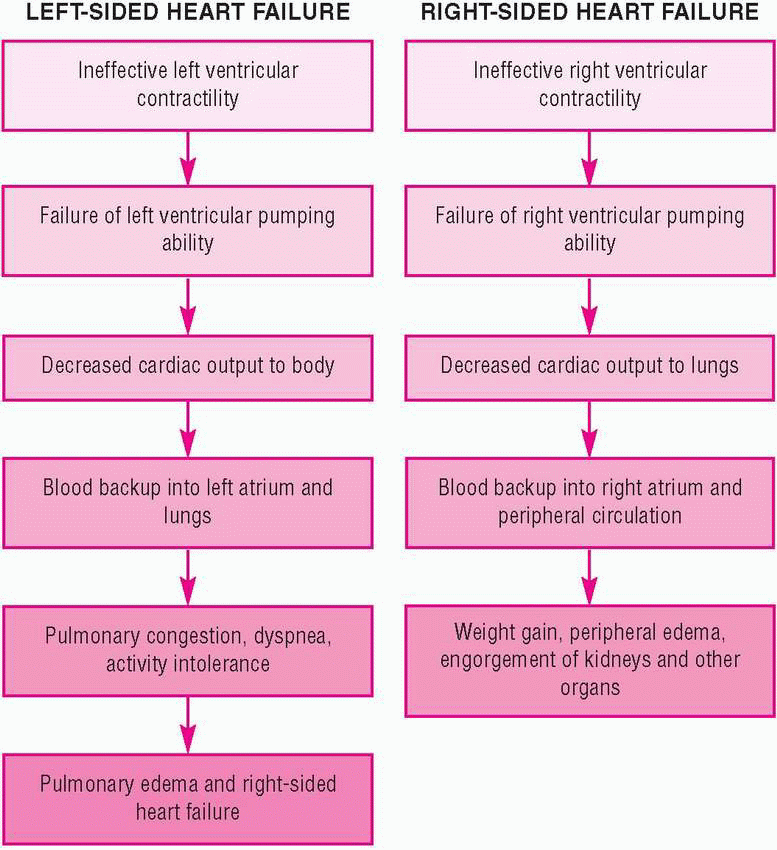

Heart failure may be classified according to the side of the heart affected (left- or right-sided failure) or by the cardiac cycle involved (systolic or diastolic dysfunction). Usually, pump failure occurs in a damaged left ventricle (left-sided heart failure), but it may occur in the right ventricle (right-sided heart failure), either as a primary disorder or as a result of left-sided heart failure. Sometimes, left- and right-sided heart failure develop simultaneously. (See What happens in heart failure, page 90.)

Congestion of systemic venous circulation (from left-sided heart failure) may result in peripheral edema or hepatomegaly. Congestion of the pulmonary circulation (from right-sided heart failure) may cause pulmonary edema, a life-threatening emergency. Although heart failure may be acute (as a direct result of myocardial infarction [MI]), it usually is a chronic disorder associated with sodium and water retention by the kidneys. Advances in diagnostic and therapeutic techniques have greatly improved the outlook for patients with heart failure, but the prognosis still depends on the underlying cause and its response to treatment.

CAUSES AND INCIDENCE

Heart failure may be caused by a primary abnormality of the heart muscle (such as infarction), by inadequate myocardial perfusion (as from coronary artery disease), or from cardiomyopathy. (See Causes of heart failure, page 92.) Other causes include:

• diastolic dysfunction, preserved ejection fraction, impairment of ventricular filling by diminished relaxation or reduced compliance in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, myocardial hypertrophy, and pericardial restriction

• mechanical disturbances in ventricular filling during diastole when there’s too little blood for the ventricle to pump, as in mitral stenosis secondary to rheumatic heart disease or constrictive pericarditis and atrial fibrillation

• systolic hemodynamic disturbances, such as excessive cardiac workload due to volume overloading or pressure overload that limit the heart’s pumping ability. These

disturbances can result from mitral or aortic insufficiency, which causes volume overloading, and aortic stenosis or systemic hypertension, which result in increased resistance to ventricular emptying. (See Left-sided and right-sided heart failure, page 93.)

disturbances can result from mitral or aortic insufficiency, which causes volume overloading, and aortic stenosis or systemic hypertension, which result in increased resistance to ventricular emptying. (See Left-sided and right-sided heart failure, page 93.)

Left-sided and right-sided

Left-sided heart failure occurs as a result of ineffective left ventricular contractile function. As the pumping ability of the left ventricle fails, cardiac output falls. Blood is no longer effectively pumped out into the body and instead backs up into

the left atrium and then into the lungs, causing pulmonary congestion, dyspnea, and activity intolerance. If the condition persists, pulmonary edema and right-sided heart failure may result. Common causes include left ventricular infarction, hypertension, and aortic and mitral valve stenosis.

the left atrium and then into the lungs, causing pulmonary congestion, dyspnea, and activity intolerance. If the condition persists, pulmonary edema and right-sided heart failure may result. Common causes include left ventricular infarction, hypertension, and aortic and mitral valve stenosis.

CAUSES OF HEART FAILURE

Cause | Examples |

|---|---|

Abnormal cardiac muscle function | ▪ Cardiomyopathy ▪ Myocardial infarction |

Abnormal left ventricular filling | ▪ Atrial fibrillation ▪ Atrial myxoma ▪ Constrictive pericarditis – Impaired ventricular relaxation: – Hypertension – Myocardial hibernation – Myocardial stunning ▪ Mitral valve stenosis ▪ Tricuspid valve stenosis |

Abnormal left ventricular pressure | ▪ Aortic or pulmonic valve stenosis ▪ Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease ▪ Hypertension ▪ Pulmonary hypertension |

Abnormal left ventricular volume | ▪ High-output states: – Arteriovenous fistula – Beriberi – Chronic anemia – Infusion of a large volume of I.V. fluids in a short time – Pregnancy – Septicemia – Thyrotoxicosis ▪ Valvular insufficiency |

Right-sided heart failure results from ineffective right ventricular contractile function. Consequently, blood isn’t pumped effectively through the right ventricle to the lungs, causing blood to back up into the right atrium and the peripheral circulation. The patient gains weight and develops peripheral edema and engorgement of the kidneys and other organs. It may result from an acute right ventricular infarction, pulmonary hypertension, or a pulmonary embolus. However, the most common cause is profound backward blood flow due to left-sided heart failure.

Systolic and diastolic

Systolic dysfunction occurs when the left ventricle can’t pump enough

blood out to the systemic circulation during systole and the ejection fraction falls. Consequently, blood backs up into the pulmonary circulation and pressure increases in the pulmonary venous system. Cardiac output falls; weakness, fatigue, and shortness of breath may occur. Causes of systolic dysfunction include MI and dilated cardiomyopathy.

blood out to the systemic circulation during systole and the ejection fraction falls. Consequently, blood backs up into the pulmonary circulation and pressure increases in the pulmonary venous system. Cardiac output falls; weakness, fatigue, and shortness of breath may occur. Causes of systolic dysfunction include MI and dilated cardiomyopathy.

Diastolic dysfunction occurs when the ability of the left ventricle to relax and fill during diastole is reduced and the stroke volume falls. Therefore, higher volumes are needed in the ventricles to maintain cardiac output. Consequently, pulmonary congestion and peripheral edema develop. Diastolic dysfunction may occur as a result of left

ventricular hvpertrophy, hypertension, or restrictive cardiomyopathy. This type of heart failure is less common than systolic dysfunction, and its treatment isn’t as clear.

ventricular hvpertrophy, hypertension, or restrictive cardiomyopathy. This type of heart failure is less common than systolic dysfunction, and its treatment isn’t as clear.

Compensatory mechanisms

All causes of heart failure lead to reduced cardiac output, which triggers compensatory mechanisms, such as ventricular dilation, hypertrophy, increased sympathetic activity, and activation of the reninangiotensin-aldosterone system. These mechanisms improve cardiac output at the expense of increased ventricular work.

In cardiac dilation, an increase in end-diastolic ventricular volume (preload) causes increased stroke work and stroke volume during contraction, stretching cardiac muscle fibers beyond optimum limits and producing pulmonary congestion and pulmonary hypertension, which in turn lead to right-sided heart failure.

In ventricular hypertrophy, an increase in muscle mass or diameter of the left ventricle allows the heart to pump against increased resistance (impedance) to the outflow of blood. This increased muscle mass also increases myocardial oxygen requirements. An increase in ventricular diastolic pressure necessary to fill the enlarged ventricle may compromise diastolic coronary blood flow, limiting the oxygen supply to the ventricle and causing ischemia and impaired muscle contractility.

Increased sympathetic activity occurs as a response to decreased cardiac output and blood pressure by enhancing peripheral vascular resistance, contractility, heart rate, and venous return. Signs of increased sympathetic activity, such as cool extremities and clamminess, may indicate impending heart failure. Increased sympathetic activity also restricts blood flow to the kidneys, causing them to secrete renin, which in turn converts angiotensin to angiotensin I, which then becomes angiotensin II, a potent vasoconstrictor. Angiotensin causes the adrenal cortex to release aldosterone, leading to sodium and water retention and an increase in circulating blood volume. This renal mechanism is initially helpful; however, if it persists unchecked, it can aggravate heart failure as the heart struggles to pump against the increased volume.

In heart failure, counterregulatory substances, such as prostaglandins and atrial natriuretic factor, are produced in an attempt to reduce the negative effects of volume overload and vasoconstriction caused by the compensatory mechanisms.

The kidneys release the prostaglandins prostacyclin and prostaglandin E, which are potent vasodilators. These vasodilators also act to reduce volume overload produced by the renin-angiotensinaldosterone system by inhibiting sodium and water reabsorption by the kidneys.

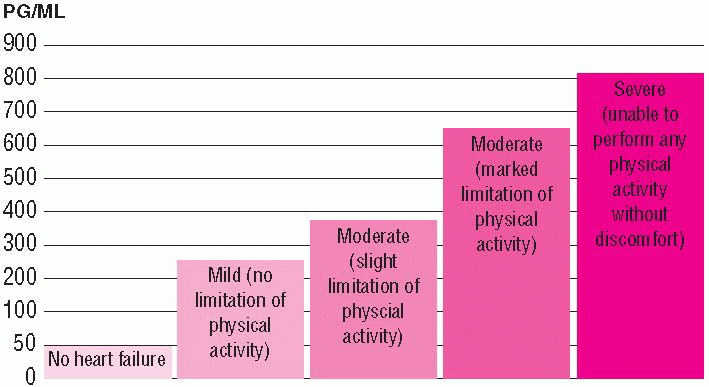

Atrial natriuretic factor is a hormone secreted mainly by the atria in response to stimulation of the stretch receptors in the atria caused by excess fluid volume. B-type natriuretic factor (BNP) is secreted by the ventricles because of fluid volume overload. These natriuretic factors work to counteract the negative effects of sympathetic nervous system stimulation and the reninangiotensin-aldosterone system by producing vasodilation and diuresis. (See How heart failure affects the body.)

HOW HEART FAILURE AFFECTS THE BODY

This summary highlights the effects of heart failure on major body systems and the multidisciplinary care it requires.

Cardiovascular system

▪ In left-sided heart failure, the pumping ability of the left ventricle fails and cardiac output falls. Blood backs up into the right atrium.

▪ In right-sided heart failure, the right ventricle becomes stressed and hypertrophies, leading to increased conduction time and arrhythmias.

Respiratory system

▪ As a result of pump failure, blood backs up into the right atrium and then into the lungs, causing pulmonary congestion.

GI system

▪ Congestion of peripheral tissues leads to GI tract congestion and anorexia, GI distress, and weight loss.

▪ Liver failure may result from blood backing up into the peripheral circulation and subsequent engorgement of organs.

Renal system

▪ With right-sided heart failure, blood backs up into the right atrium and the peripheral circulation. The patient gains weight and develops peripheral edema and engorgement of the kidneys and other organs.

Collaborative management

Multidisciplinary care is needed to determine the underlying cause and precipitating factors of heart failure, and it may include the expertise of a respiratory therapist, dietitian, and physical therapist. If the patient has coronary artery disease, severe limitations, or repeated hospitalizations despite maximal medical treatment, he may need surgery. He also may need social services to help him transition back home after the acute situation is resolved.

Chronic heart failure may worsen as a result of respiratory tract infections, pulmonary embolism, stress, increased sodium or water intake, or failure to adhere to the prescribed treatment regimen.

Heart failure affects about 2 of every 100 people ages 27 to 74. It becomes more common with advancing age.

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

Left-sided heart failure primarily produces pulmonary signs and symptoms; right-sided heart failure, primarily systemic signs and symptoms. However, heart failure commonly affects both sides of the heart.

Clinical signs of left-sided heart failure include dyspnea, orthopnea, crackles, possible wheezing, hypoxia, respiratory acidosis, cough, cyanosis or pallor, palpitations, arrhythmias, elevated blood pressure, and pulsus alternans.

Clinical signs of right-sided heart failure include dependent peripheral edema, hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, jugular vein distention, ascites, slow weight gain, arrhythmias, positive hepatojugular reflex, abdominal distention, nausea, vomiting, anorexia, weakness, fatigue, dizziness, and syncope.

COMPLICATIONS

• Pulmonary edema

• Acute renal failure

• Arrhythmias

• Multi-organ failure

• MI

DIAGNOSIS

• Electrocardiography may reflect heart strain or enlargement, ischemia, or previous MI. It may also reveal atrial enlargement, tachycardia, and extrasystoles.

• Chest X-ray shows increased pulmonary vascular markings, interstitial edema, or pleural effusion and cardiomegaly.

• Pulmonary artery pressure monitoring typically demonstrates elevated pulmonary artery and pulmonary artery wedge pressures, left ventricular end-diastolic pressure in left-sided heart failure, and elevated right atrial pressure or central venous pressure in right-sided heart failure.

• BNP is a neuro-hormone produced predominantly by the heart ventricle and is released in response to blood volume expansion or pressure overload. Blood concentrations of BNP greater than 100 pg/ml are an accurate predictor of heart failure. (See Linking BNP levels to heart failure symptom severity.)

• Echocardiography may demonstrate wall motion abnormalities and chamber dilation.

Other tests that may also demonstrate enlargement of the heart or decreased functioning include chest computed tomography scan, cardiac magnetic resonance imaging, or nuclear scans, such as multiple-gated acquisition scanning and radionuclide ventriculography.

TREATMENT

The goal of therapy is to improve pump function by reversing the compensatory mechanisms producing the clinical effects, underlying disorders, and precipitating factors. Lifestyle modifications should be employed to reduce symptoms of heart failure. These include:

• weight loss, if needed

• reduced sodium intake (to no more than 3 g daily)

• limited alcohol intake

• reduced fat intake

• smoking cessation, if needed

• stress reduction

• an exercise program.

Other treatments may include the following.

• A biventricular pacemaker may be used to control ventricular dyssynchrony.

• Coronary artery bypass surgery or angioplasty may be needed for heart failure that results from coronary artery disease.

• Valve surgery may be used to reshape and support the mitral valve and improve cardiac functioning.

• Left ventricular remodeling surgery may be used to return the ventricle to a more normal shape and allow the heart to pump blood more efficiently. This surgical technique involves cutting a wedge about the size of a small slice of pie out of the left ventricle of an enlarged heart. The remainder of the heart is sewn together. The result is a smaller organ that can pump blood more efficiently.

• A left ventricular assist device, also known as a bridge to transplantation, may be used to improve the pumping ability of the heart until transplantation can be performed.

• Heart transplantation may be needed in a patient experiencing limitations or repeated hospitalizations despite aggressive medical treatment.

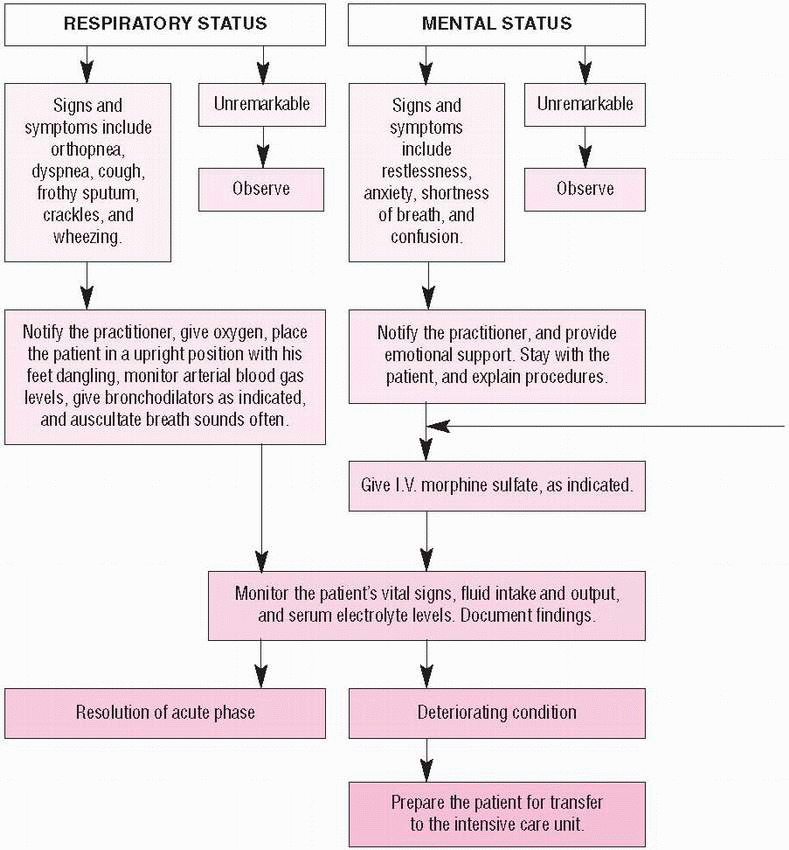

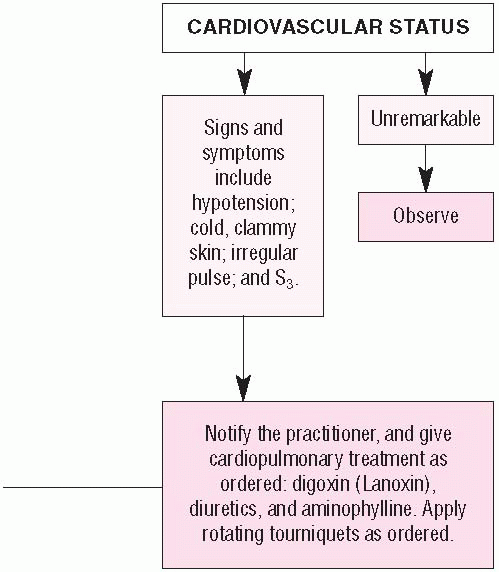

It’s important to watch for and treat complications, which typically may include venostasis with a

predisposition to thromboembolism (related mainly to prolonged bed rest), cerebral insufficiency, renal insufficiency with severe electrolyte imbalance, and pulmonary edema. (See Pulmonary edema: How to intervene.)

predisposition to thromboembolism (related mainly to prolonged bed rest), cerebral insufficiency, renal insufficiency with severe electrolyte imbalance, and pulmonary edema. (See Pulmonary edema: How to intervene.)

Drugs

• Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors for left ventricular

dysfunction to reduce production of angiotensin II, resulting in preload and afterload reduction

dysfunction to reduce production of angiotensin II, resulting in preload and afterload reduction

• Digoxin (Lanoxin) for heart failure caused by left ventricular systolic dysfunction to increase myocardial contractility, improve cardiac output, reduce the volume of the ventricle, and decrease ventricular stretch

• Diuretics to reduce fluid volume overload and venous return

• Beta-adrenergic blockers for New York Heart Association class II or III heart failure caused by left ventricular systolic dysfunction to prevent remodeling (Bisoprolol [Zebeta], sustained-release metoprolol [Lopressor], and carvedilol [Coreg] reduce death in patients with chronic heart failure)

• I.V. peripheral vasodilators (nitroglycerin, nitroprusside (Nitropress), or nesiritide [Natrecor]) and positive inotropic agents (dobutamine, dopamine, or milrinone [Primacor]) for acute treatment of worsening heart failure

• Nesiritide, a recombinant form of endogenous human BNP, to reduce sodium through its diuretic action

• Angiotensin II receptor blockers for patients who can’t tolerate ACE inhibitors

• Aldosterone blockers to treat advanced heart failure

• Diuretics, nitrates, morphine, and oxygen to treat pulmonary edema

SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree