Chapter Four

Gender Differences in the Treatment of Coronary Artery Disease

Women with coronary artery disease are undertreated and underserved. In the US alone approximately 16.8 million people have heart disease — of these 8.1 million are female. In previous chapters, we have discussed the ways in which heart disease presents differently (both biologically and clinically) in men and women. The data is clear that more women than men die from heart disease. Surprisingly to many, women’s mortality rates due to heart disease are four to six times higher than from breast cancer. Women who present with myocardial infarction are more likely to have more complicated hospital courses and have a significantly higher mortality as compared to their male cohorts.1 In fact, women presenting with cardiovascular disease are often misdiagnosed and more likely to die from their first cardiac event.2 In the CRUSADE trial it was found that approximately 30% of patients presenting with ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) were women and female sex was an independent predictor of failure to receive prompt reperfusion therapy even though the data supports early revascularization in STEMI patients.1 In other clinical trials, women were found to present later, have longer door-to-balloon times, longer door-to-fibrinolysis times and were less likely to be treated with aspirin and beta-blockers within 24 hours of presentation.3 It is clear that there is a significant gender gap in the care of an acute coronary syndromes — this gap must be addressed in order to improve the mortality rates in women with cardiovascular disease. Unless we recognize the problem and begin to educate ourselves, our colleagues and our patients, little will be done to impact survival rates of women with heart disease.

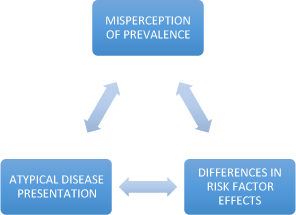

To impact change, we must all have a better understanding of why there is a dichotomy in cardiac care between men and women in the first place — certainly disease presentation plays a significant role. In addition, there is an erroneous public perception that heart disease is predominantly a disease of men. In order to understand why we see some differences in disease presentation and why public perception of the demographics of the disease is flawed we must again consider biological differences in men and women. As discussed in previous chapters, women often present with more diffuse coronary artery disease, more atypical symptoms and often present much later in the course of their illness. Women are affected differently by risk factors — for instance, women with diabetes are more likely to develop heart disease than men. In addition, cholesterol abnormalities such as low HDL (high-density lipoprotein) in women confer a much higher risk for the development of coronary artery disease. In women, hyperlipidemia, in particular LDL (low-density lipoprotein) abnormalities, seem to peak a decade later than men (around age 65) but a meta-analysis showed an increased risk of heart disease in women younger than 65 who do have elevated lipids, as compared to men with similar elevations.4

Figure 4.1 Biologic factors contributing to disparities in cardiovascular care in women.

Evidence from numerous clinical trials over the last several decades has made the evaluation and treatment of acute coronary syndrome (ACS), including both non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) as well as STEMI quite clear.5,6 The American College of Cardiology has developed guidelines that are well supported by the best available evidence. In NSTEMI and unstable angina, expert consensus recommends an early invasive strategy in high-risk patients — those with positive biomarkers and those with any hemodynamic instability or refractory chest pain. In the setting of STEMI, experts recommend prompt revascularization via primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) in PCI-capable facilities. In the case of STEMI in a facility not capable of PCI, either thrombolytic therapy or rapid transfer to a PCI-ready facility is recommended. Obviously, treatment with aspirin, beta-blockers, nitrates and anticoagulation with heparin, enoxaparin as well as the addition of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors is indicated in cases of NSTEMI as well as peri-PCI in STEMI cases undergoing revascularization.

Most emergency departments and emergency management systems (EMS) have well-established protocols in place for the pre-hospital management of potential ACS patients. These protocols are aimed at reducing delays in diagnosis and treatment. While not every hospital is PCI-capable, there are significant increases in mortality associated with delays in treatment after arrival to the hospital.7 Many EMS providers are able to transmit real-time EKG tracings to ER physicians for rapid interpretation. There is a growing body of evidence to support pre-hospital administration of thrombolytic therapy when transporting a patient to a non-PCI capable hospital if a qualified EMS team and physician are able to effectively communicate during the process of evaluation and treatment.8 On arrival to the emergency department, treatment decisions are more rapidly made when pre-hospital care is initiated in indicated patients. Research has proven that prompt diagnosis and treatment is critical.

Over the last 20 years, advances in both the medical and early invasive strategies to treat ACS have resulted in significant reductions in mortality in men. However, in women rates of death from ACS and cardiovascular disease continue to either level off or continue to rise.9 There is accumulating evidence that suggests that early intervention and revascularization in patients with NSTEMI reduces rates of subsequent cardiac events and death. However, there is also data that complication rates (particularly bleeding risks) in the setting of acute intervention are higher in women as compared to men. Adding to the difficulty in treating women, the presenting EKG in the emergency department is much less likely to be diagnostic and more women present with NSTEMI and ST depression than with classic STEMI. Biomarkers, a cornerstone in diagnosis and prognosis in myocardial infarction, also appear to be less often elevated in women on initial presentation.10 We know that the presence of an elevated troponin in a NSTEMI is a hallmark for worse prognosis in both sexes and argues for a more aggressive, invasive approach to therapy. However, women with positive biomarkers often are not treated with the recommended early invasive strategy due to concerns over increased bleeding and complication rates.

The higher mortality rates in women with heart disease is fact — not just perception. Data from multiple registries and several retrospective studies have shown that women are not treated as aggressively as men. Women undergo less angiography and fewer coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) procedures.11 In fact, even women with documented heart disease and subsequent cardiac events are much less likely to receive thrombolytic therapy and undergo invasive procedures such as coronary angiography and revascularization as compared to men.12 In addition, women who do have invasive procedures tend to have higher complication rates.13 Women who do undergo an invasive strategy are found to have smaller coronary arteries, more diffuse and widespread disease . Early data from Circulation in 1993 demonstrated that women undergoing CABG procedures have excess mortality and most of this is due to heart failure, smaller coronary arteries and fewer left internal mammary (LIMA) grafts.14

In a large meta-analysis conducted by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Policy (AHRQ) randomized controlled trials from 2001 to 2011 that compared treatment strategies and sex-specific differences were evaluated.15 The purpose of the analysis was to examine treatment strategies in the setting of acute myocardial infarction in both men and women and compare results. The findings were quite powerful. In women presenting with an acute STEMI an early, aggressive invasive strategy with cardiac catheterization and PCI was far superior to fibrinolysis in reducing further cardiovascular events. In addition, the study also found a trend that in women with unstable angina, an early invasive strategy was also superior in reducing future events. Most significantly, the analysis also found that when comparing revascularization to conservative medical therapy in women the invasive strategy was associated with improved outcomes. By contrast, the outcomes and event rate for either treatment strategy was similar in male patients. However, in spite of these findings men continue to be treated more aggressively and more often with an early invasive approach, as compared to women presenting in similar fashion.

Not only are women treated differently when presenting with an acute event, evidence suggests that they are also treated differently during the recovery period after an acute cardiac event and at discharge. Some studies indicate that guideline-based therapies are not equally applied in men and women. Even more disturbing is the fact that women who are discharged after acute myocardial infarction are less likely to be prescribed appropriate, evidence-based medications, such as aspirin, ACE inhibitors, beta-blockers and cholesterol-lowering agents. These women have been shown to have higher rates of re-hospitalization and debilitating refractory ischemia. In fact, women, particularly if older, Hispanic or African American are even less likely to receive these evidence-based medications that have been shown to confer mortality benefits in major clinical trials.

Although we have long been aware that post-event counseling and lifestyle modification has been associated with decreased rates of subsequent events, women also seem to receive much less pre-discharge counseling. When treating women with ACS, there seems to be less focus on risk factor modification, lifestyle changes and secondary prevention as compared to men. Data from numerous studies have shown that in women presenting with ACS the rates of obesity, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia and obesity are much higher than in men.16 Only smoking is more prevalent in men with heart disease. However, smoking is a major risk factor for women as well and in women presenting with ACS that are under the age of 50 nearly 60% of these events are attributable to tobacco abuse. There is good evidence to suggest that all women with coronary artery disease benefit from smoking cessation.17 Interestingly, studies show that women tend to have more difficulty with smoking cessation than men and without treatment and counseling are more likely to relapse and begin smoking again. Yet with all these increased modifiable risk factors, women continue to receive fewer interventions aimed at secondary prevention even prior to discharge from the hospital following an acute cardiac event. In a study examining risk factor modification and outcome after ACS, researchers found that women were less likely to achieve target blood pressure, lipids and blood sugars over a six-year follow-up period.18 Clearly, as a whole, we are doing a very poor job in treating women after an acute cardiac event. We have many missed opportunities for intervention and secondary prevention.

An important component to the effective treatment of coronary artery disease is the outpatient care in the months to years following an acute event. As discussed above, risk factor modification and lifestyle changes are very important in both men and women. In addition, cardiac rehabilitation can be an important part of recovery. Unfortunately, women are not as likely to be referred to cardiac rehabilitation (as compared to men) and are less likely to participate in organized rehabilitation activities.19 One study in particular found that recovery goals differed significantly between the sexes and may explain some of the differences in rehabilitation participation. In this investigation, women placed higher importance on returning to household duties whereas men were more concerned with developing physical endurance and returning to work quickly.20 Studies have shown that cardiac rehabilitation referral after an acute coronary event by physicians has been biased against the elderly and women in particular.21 Cardiac rehabilitation has been associated with improved outcomes and is an essential part of recovery after myocardial infarction and in particular CABG procedures.22 It has further been proven that patients who either do not attend or attend rehab sessions less than 25% of the time have more than double the mortality rate of those with more regular attendance.23 In addition, participation in rehabilitation programs is associated with a much higher rate of smoking cessation in cardiac patients — an essential part of secondary prevention.24 Yet again, we miss these secondary prevention opportunities with our female patients.

We have clear evidence for the most effective treatments for ACS and coronary artery disease that is based on many years of work and several very large randomized controlled clinical trials. We also have a growing body of evidence for post-cardiac-event interventions including risk factor modification and lifestyle changes that clearly result in decreased mortality and reduction in subsequent events. However, the evidence suggests that women are not treated as aggressively as men in the acute setting and fewer interventions are made in the post-event period as well. Ultimately, we are missing the mark in treating women — we must apply the same guidelines and standards of care to both sexes in order to achieve more equitable outcomes.

1 Gharacholou, S. M., Alexander, K. P., Chen, A. Y. et al. (2010). Implications and reasons for the lack of use of reperfusion therapy in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: findings from the CRUSADE initiative. Am Heart J, Volume 159, 757–763.

2 Kudenchuk, P. J., Maynard, C., Martin, J. S. et al. (1996). Comparison of presentation, treatment, and outcome of acute myocardial infarction in men versus women (the Myocardial Infarction Triage and Intervention Registry). Am J Cardiol, Volume 78, 9–14.

3 Subherwal, S., Bach, R. G., Chen, A. Y. et al. (2009). Baseline risk of major bleeding in non-ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction: the CRUSADE (Can Rapid risk stratification of unstable angina patients suppress adverse outcomes with early implementation of the ACC/AHA Guidelines) Bleeding Score. Circulation, Volume 119, 1873–1882.

4 Manolio, T. A., Pearson, T. A., Wenger, N. K. et al. (1992). Cholesterol and heart disease in older persons and women. Review of an NHLBI workshop. Ann Epidemiol. Volume 2, 161–176.

5 O’Gara, P. T., Kushner, F. G., Ascheim, D. D. et al. (2013). ACCF/AHA Guideline for the Management of ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction: A Report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. Volume 61(4), e78–e140.

6 2011 Writing Group Members, Wright, R. S., Anderson, J. L., Adams, C. D. et al. (2011). ACCF/AHA Focused update of the guidelines for the management of patients with unstable angina/non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction (updating the 2007 guideline). Circulation, Volume 123, 2022–2060.

7 Rathore, S. S., Curtis, J. P. , Chen, J. et al. (2009). Association of door-to-balloon time and mortality in patients admitted to hospital with ST elevation myocardial infarction: national cohort study. BMJ, Volume 338, b1807.

8 Roth, A., Barbash, G. I., Hod, H. et al. (1990). Should thrombolytic therapy be administered in the mobile intensive care unit in patients with evolving myocardial infarction? A pilot study. J Am Coll Cardiol, Volume 15, 932–936.

9 Elsaesser, A. and Hamm, C. W. (2004). Acute coronary syndrome: the risk of being female. Circulation, Volume 109, 565–567.

10 Wu, A. H. B., Apple, F. S., Gibler, W. B. et al. (1999). National Academy of Clinical Biochemistry Standards of Laboratory Practice: Recommendations for the use of cardiac markers in coronary artery diseases. Clin Chem, Volume 45, 1104–1121.

11 Anand, S. S., Xie, C., Mehta, S. et al. (2005). Differences in the management and prognosis of women and men who suffer from acute coronary syndromes. J Am Coll Cardiol, Volume 46(10), 1845–1851.

12 Weitzman, S., Cooper, L., Chambless, L. et al. (1997). Gender, racial, and geographic differences in the performance of cardiac diagnostic and therapeutic procedures for the hospitalized acute myocardial infraction in four states. Am J Cardiol, Volume 79, 722–726.

13 Johnstone, N., Schenck-Gustafsson, K. and Lagerqvist, B. (2011). Are we suing cardiovascular medications and coronary angiography appropriately in men and women with chest pain? European Heart J, Volume 32, 1331–1336.

14 O’Connor, G. T., Morton, J. R., Diehl, M. J. et al. (1993). Differences between men and women in hospital mortality associated with coronary bypass graft surgery. Circulation, Volume 88, 2104–2110.

15 Dolor, R. J., Melloni, C., Chatterjee, R . et al. (2012). Treatment strategies for women with coronary artery disease. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2012 Aug. Comparative Effectiveness Reviews, No. 66.

16 Shehab, A., Yasin, J., Hashim, M. J. et al. (2012). Gender differences in acute coronary syndrome in Arab Emirati women — implications for clinical management. Angiology, Volume 64(1), 9–14.

17 Kawachi, I., Colditz, M. B., Stampfer, M. J. et al. (1994). Smoking cessation and time course of decreased risks of coronary heart disease in middle-aged women. Arch Intern Med, Volume 154, 169–175.

18 Reibis, R. K., Bestehorn, K., Pittrow, D. et al. (2009). Elevated risk profile of women in secondary prevention of coronary artery disease: a 6-year survey of 117,913 patients. J Womens Health (Larchmt), Volume 18(8), 1123–1131.

19 Grande, G. and Romppel, M. (2011). Gender differences in recovery goals in patients after acute myocardial infarction. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev, Volume 31(3), 164–172.

20 Ibid.

21 Cottin, Y., Cambou, J. P., Cassilas, J. M. et al. (2004). Specific profile and referral bias of rehabilitated patients after an acute coronary syndrome. J Cardiopulm Rehabil, Volume 24(1), 38–44.

22 Pack, Q. R., Goel, K., Lahr, B. D. et al. (2013). Participation in cardiac rehabilitation and survival following coronary artery bypass graft surgery: a community based study. Circulation, Volume 128, 590–597.

23 Beauchamp, A., Worcester, M. Ng, A. et al. (2013). Attendance at cardiac rehabilitation is associated with lower all-cause mortality after 14 years of follow-up. Heart, Volume 99, 620–625.

24 Dawood, N., Vaccarino, V., Reid, K. J. et al. (2008). Predictors of Smoking Cessation After a Myocardial Infarction: The Role of Institutional Smoking Cessation Programs in Improving Success. Arch Intern Med, Volume 168(18), 1961–1967.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree