Chapter Three

Gender Differences in Testing and Evaluation

The diagnosis of coronary artery disease can be challenging. Gender differences in patient presentation and biological differences in the extent and in the progression of cardiovascular disease make the evaluation of risk in women even more complex. While men are more likely to have discrete lesions within the coronary arteries, angiographic studies have shown that women have more diffuse disease — these types of abnormalities are much harder to detect on routine testing. However, one study has demonstrated that when women do have typical symptoms, they are more likely to have more significant, life-threatening disease. Moreover, it has been shown that over the last several decades, mortality from heart attack is much higher in women than in men. These higher cardiovascular disease mortality rates makes early detection and prevention an even more pressing matter in women as compared to men. Unfortunately, routine testing and, even more con cerning, follow-up testing, is less likely to be applied in women as compared to men.

When approaching a patient suspected of having coronary artery disease, healthcare providers must approach both sexes equally. Although it is vital to understand and incorporate gender differences into formulating plans for evaluation, we must consider the fact that women are in fact undertreated and underserved. From a clinical standpoint, physicians must evaluate risk factors (in both sexes) and develop a pre-test probability for the presence or absence of disease. Pre-test probabilities are defined as the subjective likelihood of the presence of a disease prior to diagnostic testing. Properly predicting the pre-test probability of disease is integral to choosing the proper diagnostic testing strategy. It is important to consider the use of Bayes’ theorem for determining the appropriate testing and workup of a woman presenting with possible coronary artery disease.1 By applying Bayes’ principles, we are able to select the best test for evaluating a particular female patient — providing the highest possible yield while at the same time limiting false positive results.

Another important factor in choosing and successfully performing a diagnostic test is determining the prevalence of the disease. Prevalence is defined as the proportion of the population found to have the disease. Younger women typically have a low prevalence of coronary artery disease and tend to present later in life with more severe disease.

However, some testing can be more accurate in men when compared to women. For instance, some types of exams, such as exercise stress testing, yield higher rates of false negative results in women. Further compounding this issue is the fact that women who have symptoms of heart disease are less likely to be referred for further diagnostic testing.2

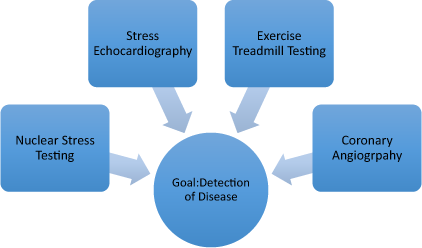

In the US today, exercise stress testing is the most common and most cost-effective screening test for the evaluation for coronary artery disease in both men and women.3 In women who have an intermediate pre-test probability of coronary artery disease the American College of Cardiology recommends the addition of imaging such as either echocardiography or nuclear SPECT to exercise stress testing in order to improve yield. However, these imaging tests tend to be a bit less accurate in women as compared to men. For instance, nuclear stress testing in women tends to produce more false positives due to breast attenuation defects that can be mistaken for areas of myocardial ischemia. In addition, the size of the left ventricular cavity is smaller in women and the coronary arteries tend to be smaller in women as compared to men and both of these factors make SPECT stress testing less accurate. Exercise echocardiography can also be useful in detecting coronary artery disease in women. However, due to body habitus, acoustic windows for obtaining adequate images for interpretation are often more limited in women. When a meta-analysis was performed comparing the accuracy of nuclear SPECT versus stress echocardiography imaging in women, no difference was found. The sensitivity and specificity of both methods were comparable in women yet, when compared to men, there were more false positives.4 Importantly, in another study, women with no evidence of electrocardiography (EKG) or echocardiographic abnormalities during stress testing had a remarkable cardiac event free survival (>96%). In contrast, women with abnormalities and evidence of ischemia have a very high event rate and event free survival is much lower (<55%).5

Figure 3.1 Detection of cardiovascular disease: testing options.

As with most diagnostic testing, there are risks to the patient associated with each modality that must be considered when choosing appropriate diagnostic testing. These exposure risks are actually different in men and women with women requiring higher doses in order to produce similar image quality. With nuclear SPECT imaging and cardiac CT scanning there are finite risks associated with radiation exposure. The most common radioisotope utilized for stress testing is technetium-99m (Myoview). In the stress test protocol women receive 10.57 mSv (millisieverts) versus 8.81 mSv for men. The Health Physics Society estimates that exposures below 500 mSv most often have no visible effects at the time of the exposure. To put this in perspective, all of us receive “background radiation” exposure annually in the amount of 4 mSv — therefore, a stress test accounts for the equivalent of nearly three years of background radiation exposure. CT scanning accounts for higher radiation doses than SPECT imaging. The doses of radiation that we receive are cumulative and risks increase over time. In the US alone, it is estimated that nearly 2% of cancers are due to radiation exposures during diagnostic testing.6 Radiation exposure has been associated with the development of certain types of cancers including lymphomas and certain types of leukemias. When evaluating women of childbearing age it is important to ensure that they are not pregnant before undertaking a test that involves radiation exposure.

What’s the best way to evaluate women for heart disease?

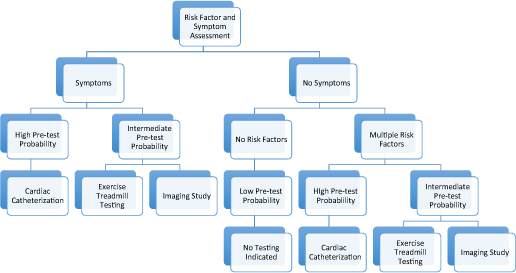

The American College of Cardiology (ACC) has produced an algorithm for the evaluation of heart disease in women. Based on the best available data, the recommended approach is as follows: initial evaluation must consist of an assessment of risk factors and symptoms. Once the initial evaluation is performed, women should be divided into two categories — those with symptoms and those without symptoms. In asymptomatic women, no stress testing is recommended unless there are other high-risk features such as significant family history of premature heart disease, or a combination of several other traditional risk factors. The ACC recommends further that the initial test of choice should be an exercise EKG test — unless there are issues that may preclude interpretation, such as a left bundle branch block or the inability to adequately exercise to the appropriate level on the treadmill. In fact, the pre-test probability of finding coronary artery disease in asymptomatic women without significant risk factors (in all age groups) is quite low. In contrast, women who have symptoms require much more comprehensive evaluation. Even in women aged 30–60 with classic symptoms of angina, the pre-test probabilities are intermediate. However, in those who are older than 60 with classic symptoms, the pre-test probabilities are quite high for coronary artery disease. Moreover, women with atypical symptoms whom are older than 50 also have an intermediate-to-high-risk pre-test probability of having disease.

According to the ACC, in women with symptoms and normal baseline EKG (along with the ability to exercise) the exercise treadmill test is the test of choice. The Duke Activity Index is a questionnaire that can be used to determine if a potential patient will be able to adequately exercise during a treadmill test.7, 8 If the functional capacity is determined to be less than 5 METS (metabolic equivalent of tasks), then a pharmacologic test is indicated. If an exercise stress test is negative, the negative predictive value for coronary artery disease is quite low. However, if the test is inconclusive or positive in any way, further evaluation with either imaging-based testing or angiography is immediately indicated. A negative stress test with imaging will essentially rule out the presence of coronary artery disease in the majority of cases. Unfortunately, many women do not receive the comprehensive evaluation, screening and testing that is outlined above. In many cases, asymptomatic women with risk factors or women with atypical symptoms and risk factors are often not even evaluated with the indicated EKG and/ or EKG exercise stress testing. Moreover, many women who are evaluated and found to have indeterminate results are not sent along for further evaluation with either an imaging stress test or coronary angiography. These lapses in the diagnostic workup then leads to many preventable cardiac events in women.

Figure 3.2 Proposed algorithm for the evaluation of heart disease in women.

1 Rifkin, R. D. and Hood, W. B. Jr. (1977). Bayesian analysis of electrocardiographic exercise stress testing. N Engl J Med, Volume 297, 681–686.

2 Daugherty, S. L., Peterson, P. N., Magid, D. J. et al. (2008). The relationship between gender and clinical management after exercise stress testing. Am Heart J, Volume 156, 301–307.

3 Cohen, M. C., Stafford, R. S. and Misra, B. (1999). Stress testing: national patterns and predictors of test ordering. Am Heart J, Volume 138, 1019–1024.

4 Grady, D., Chaput, L. and Kristof, M. (2003). Diagnosis and treatment of coronary heart disease in women: systematic reviews of evidence on selected topics: evidence report/technology assessment No. 81 (prepared by the University of California, San Francisco–Stanford Evidence-Based Practice Center under contract No. 290-97-0013). Stanford Evidence-Based Practice Center. AHRQ publication No. 03-E037.

5 Heupler, S., Mehta, R., Lobo, A. et al. (1997). Prognostic implications of exercise echocardiography in women with known or suspected coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol, Volume 30, 414–420.

6 Mathews, J. D., Forsythe, A. V., Brady, Z. et al. (2013). Cancer risk in 680 000 people exposed to computed tomography scans in childhood or adolescence: data linkage study of 11 million Australians. BMJ, Volume 346, f 2360. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f 2360.

7 Bairey Merz, C. N., Olson, M., McGorray, S. et al. (2000). Physical activity and functional capacity measurement in women: a report from the NHLBI-sponsored WISE study. J Womens Health Gend Based Med, Volume 9, 769–777.

8 Shaw, L. J., Olson, M. B., Kip, K. et al. The value of estimated functional capacity in estimating outcome: results from the NHLBI-sponsored Women’s Ischemia Syndrome Evaluation (WISE) study. J Am Coll Cardiol, Volume 47, S36–S43.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree