Chapter Two

Gender Differences in Disease Manifestation and Presentation

Men and women manifest chronic diseases in predictable ways. We are, of course, of the same species and composed of the same basic genetic materials; however, there are important differences that can change the way in which a disease may present and progress. Cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of death in both sexes but heart disease may develop in each gender in significantly different ways. Hormonal differences between men and women not only determine our outward appearances and gender-specific sexual development but may also have a significant impact on how our bodies are affected by certain risk factors and respond to a particular disease process. In addition, exogenous hormone therapies may also have a significant impact on how patients respond to a disease over time.

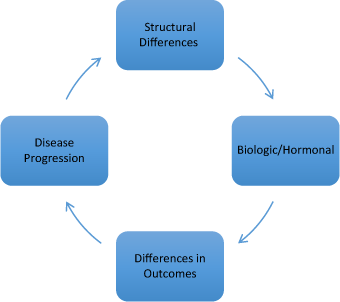

The best way to address the complex issue of gender-specific manifestations of heart disease (and response to therapy) is to break down the differences into several categories:

1. Structural Differences

2. Biologic/Hormonal Differences

3. Differences in Disease Progression

4. Differences in Response to Therapy and Outcomes

Figure 2.1 Factors affecting cardiovascular disease in women.

Structural differences

Although we share developmental and embryologic similarities, there are structural differences in the cardiovascular systems of men and women. The heart begins to form during week five of development and develops from splanchnic mesenchyme. When completely developed, women’s hearts are smaller than men’s. This is mainly a result of body size: a smaller body size equates to a proportionally smaller heart size. In addition, blood vessels in women are smaller. Hormones such as estrogen and progesterone promote development of smaller blood vessels (particularly coronary arteries) in women. Smaller blood vessels are more likely to form plaques that become unstable and rupture in the setting of an acute myocardial infarction. The smaller size of the coronary arteries results in more technically difficult angioplasty and stenting procedures. These smaller coronary arteries are more likely to tear or dissect during a percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI).

Biologic differences

Obviously there are significant biologic and hormonal differences between men and women. Although both men and women have some levels of all of the sex hormones — estrogen, progesterone, and testosterone — these levels are very different in each gender. Higher levels of estrogens and progesterone with lower levels of testosterone (commonly seen in most pre-menopausal females) can have a significant impact on the manifestations and progression of coronary artery disease. In men, elevated levels of testosterone promote the formation of larger coronary arteries and blood vessels. Women, in contrast, have higher levels of estrogen and progesterone and form smaller blood vessels. Estrogen has been shown to be protective for pre-menopausal women and reduces their risk of heart disease. However, the precipitous drop in estrogen levels at the time of menopause is associated with a significant increase risk for coronary events.

Differences in disease progression

Acute myocardial infarction occurs when there is a complete occlusion of a coronary artery. The acute closure of the artery most often occurs due to the rupture of a vulnerable plaque. These vulnerable plaques are made of fats, cholesterol and inflammatory cells called macrophages. Interestingly, these plaques appear to be biologically different in men versus women. In men, these plaques are often heavily calcified and hard. In contrast, many of these plaques in women tend to be a bit softer, less calcified and more prone to rupture.1 Moreover, many women who suffer from acute myocardial infarction have no significant angiographically demonstrable disease at cardiac cathet erization, but have evidence of plaque ulceration and rupture.2 Many researchers postulate that the smaller size of women’s coronary arteries may contribute to this type of non-obstructive plaque rupture. Women also tend to have more widespread disease, and disease that is less likely to be classified as high-grade obstructions; instead, they are more likely to have mild to moderately obstructive disease.3 Studies have shown that patients with mild to moderately obstructive disease are prescribed evidence-based secondary prevention therapies at much lower rates than those with more significant obstructions.4

Differences in response to therapies and outcomes

We have discussed several structural and biologic/hormonal gender differences, as well as differences in disease progression, earlier in this chapter. In addition to these differences in disease manifestation, there are also gender differences in how patients may respond to therapy. Fortunately, today there are many evidence-based therapies for the treatment of heart disease. These therapies range from cardio-protective drugs, such as beta-blockers and ACE inhibitors, to cholesterol-lowering drugs, such as statins, and all have been shown to reduce mortality in appropriate patients. Certain drugs such as ACE inhibitors have been shown in a few clinical trials to have more profound effects in women as compared to men.5 Moreover, certain drugs have different pharmacokinetics in women as compared to men and require careful dose adjustment. Studies have shown that certain drug combinations are associated with better outcomes in women, particularly beta-blocker/ diuretic combination therapies.6 Healthcare providers must be aware of which combinations are most efficacious for our patients and ensure that women are treated with the appropriate evidence-based medications.

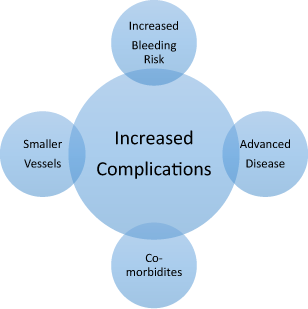

As previously mentioned, many women do not seem to receive the same aggressive treatments for heart disease as compared to men. The data clearly supports an early invasive approach in patients with acute ST-segment myocardial infarction with a goal of prompt revascularization. In cases of non-ST-elevation myocardial intarction (NSTEMI), higher-risk patients (those with a positive troponin) also benefit from an early invasive approach. While all invasive cardiac procedures are associated with a finite risk for complication, men seem to experience fewer complications than their female counterparts. Many clinicians are more reluctant to send women to invasive procedures because of the fact that they have been shown to have higher complication rates; this is despite the fact that overall outcomes are improved with this strategy. In women undergoing cardiac catheterization and revascularization, bleeding and adverse vascular events requiring transfusion or intervention are more common.7–9 These adverse events can range from bleeding and femoral hematomas to vascular compromise requiring surgical repair. Many of these complications can lead to prolonged hospitalization and longer recovery times. However, more recent studies have shown that while women continue to have higher complication rates with cardiac catheterization and intervention, these rates are declining.10 One possible explanation for the reduction in complication rates in women may be the increasing use of radial access techniques (as opposed to the traditional femoral approach) in women over the last decade. A comparison of women undergoing cardiac catheterization and revascularization via femoral versus radial techniques has shown a significant decrease in procedure-related complication rates in women who were accessed via the radial approach.11

Figure 2.2 Factors associated with higher complication rates in women.

The trend toward higher complications for women is also noted in women undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG). As compared to men, women have higher rates of morbidity and mortality with CABG.12 There are many reasons that may explain these findings including the fact that women often present for revascularization surgery with more co-morbidities, or more advanced disease. Women also were found to have more diabetes, more hypertension and pre-existing cerebro-vascular disease. In addition, from a technical aspect, women tended to have less available arterial grafts and their procedures were more often determined to be urgent or emergent. Overall, both peri-operative and post-operative cardiac and neurologic complications are higher in women as compared to men.13

We are fortunate to have many advanced therapies to treat heart disease in the modern era. These therapies have been proven in large clinical trials to reduce mortality and improve outcome. Female patients account for a significant proportion of cardiovascular events yet treatments and outcomes often differ from those in males. Disease presentation and progression is affected by numerous gender-specific factors and can impact the effectiveness of our available therapies. In order to improve outcomes in women, we must continue to apply data-driven therapies to both sexes, but with a better understanding of the biologic, hormonal and structural factors that may affect they way in which patients may respond.

1 Bairey Merz, C. N., Shaw, L. J., Reis, S. E. et al. (2006). Insights from the NHLBI-sponsored WISE study, part II: gender differences in presentation, diagnosis, and outcome with regard to gender-based pathophysiology of atherosclerosis and macrovascular and microvascular coronary disease. J Am Coll Cardiol, Volume 47, S21–S29.

2 Reynolds, H. R., Srichai, M. B., Iqbal, S. N. et al. (2011) Mechanism of myocardial infarction in women without angiographically obstructive coronary artery disease. Circulation, Volume 124, 1414–1425.

3 Smilowitz, N. R., Sampson, B. A., Abrecht, C. R. et al. (2011). Women have less severe and extensive coronary atherosclerosis in fatal cases of ischemic heart disease: an autopsy study. Am Heart J, Volume 161, 681–688.

4 Maddox, T. M., Ho, P. M., Dai, D. et al. (2010). Utilization of secondary prevention therapies in patients with nonobstructive coronary artery disease identified during cardiac catheterization. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes, Volume 3, 632–641.

5 Seeland, U. and Regitz-Zagrosek, V. (2012). Sex and gender differences in cardiovascular drug therapy. Handb Exp Pharmacol, Volume 214, 211–236.

6 Wassertheil-Smoller, S., Psaty, B., Greenland, P. et al. (2004). Association between cardiovascular outcomes and antihypertensive drug treatment in older women. JAMA, Volume 292(23), 2849–2859.

7 Peterson, E. D., Lansky, A. J., Kramer, J. et al. (2001). Effect of gender on the outcomes of contemporary percutaneous coronary intervention. Am J Cardiol, Volume 88, 359–364.

8 Argulian, E., Patel, A. D., Abramson, J. L. et al. (2006). Gender differences in short-term cardiovascular outcomes after percutaneous coronary interventions. Am J Cardiol, Volume 98, 48–53.

9 Tavris, D. R., Gallauresi, B. A., Dey, S. et al. (2007). Risk of local adverse events by gender following cardiac catheterization. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf, Volume 16, 125–131.

10 Ahmed, B., Piper, W. D., Malenka, D. et al. (2009). Significantly improved vascular complications among women undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: a report from the Northern New England Percutaneous Coronary Intervention Registry. Circulation, Volume 2, 423–429.

11 Pristipino, C., Pelliccia, F., Granatelli, A. et al. (2007). Comparison of accessrelated bleeding complications in women versus men undergoing percutaneous coronary catheterization using the radial versus femoral artery. Am J Cardiol, Volume 99(9), 1216–1221.

12 Woods, S. E., Noble, G., Smith, J. M. et al. (2003). The influence of gender in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass graft surgery: an eight-year prospective hospitalized cohort study. Journal of the American College of Surgeons, Volume 196(3), 428–434.

13 Hogue, C. W., Sundt, T. III, Barzilai, B. et al. (2001). Cardiac and neurologic complications identify risks for mortality for both men and women undergoing coronary artery bypass graft surgery. Anesthesiology, Volume 95(5), 1074–1078.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree