Fungal and Parasitic Infection

Fungal and parasitic infections are an increasingly frequent cause of pulmonary disease worldwide. Increased risk for the development of infection has resulted because of expanding population in endemic areas; increased travel to endemic areas; and increased numbers of immunocompromised patients (1). A high index of suspicion is required to diagnose fungal and parasitic infection, particularly in patients who do not reside in endemic areas.

The most common endemic mycosis in North America is histoplasmosis; other relatively common endemic mycoses are coccidioidomycosis and blastomycosis (1,2). Although most of these infections in nonimmunocompromised persons are self-limited, some patients can develop severe pneumonitis, as well as various forms of chronic pulmonary infection. Paracoccidioidomycosis (South American blastomycosis) is endemic in South America, and it carries a high mortality rate in countries such as Brazil (3).

Several mycoses are ubiquitous but almost exclusively affect predisposed persons, particularly immunocompromised patients. These mycoses include cryptococcosis, aspergillosis, candidiasis, and mucormycosis, and those caused by Pneumocystis jiroveci. The number of persons at risk for developing pulmonary infection from these organisms continues to grow (4,5). In this chapter we focus on the radiologic manifestations of pulmonary mycoses and parasitic infestations seen in nonimmunocompromised persons. Infections in immunocompromised patients are discussed in Chapters 7 and 8.

Fungi

Histoplasmosis

Histoplasmosis is caused by the dimorphic fungus Histoplasma capsulatum. It is endemic in the Mississippi and Ohio river valleys in the United States, the St. Lawrence river valley in Canada, and South America (1). The manifestations of pulmonary disease are quite varied. The most common pathologic abnormality is focal granulomatous inflammation, necrosis, and fibrosis, identical to that of tuberculosis. This disease is usually too limited in extent to be visible on chest radiography and is not recognized clinically. Occasionally, enlargement or coalescence of several inflammatory foci results in single or multiple poorly defined areas of airspace consolidation (6). In most patients, ipsilateral hilar lymph node enlargement is evident on the radiograph.

A much more common clinical presentation is that of a solitary nodule seen on chest radiography or computed tomography (CT) scan in an asymptomatic patient (see Table 6.1). The nodule corresponds histologically to an

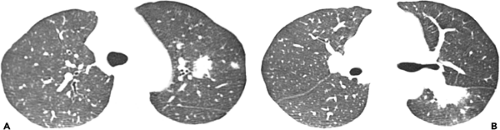

encapsulated focus of necrotizing granulomatous inflammation that develops in the same manner as the Ghon focus of tuberculosis. Nodules that have been present for more than a few months frequently show central (target) or diffuse calcification as a result of dystrophic calcification of the necrotic material (see Fig. 6.1). Calcified nodules are frequently associated with calcified hilar and mediastinal lymph nodes (6). The scenarios described in the preceding text are often unassociated with a clear history of exposure to a source of infection. Exposure to a relatively large number of organisms, such as during excavation of a contaminated work site or while exploring contaminated caves, may result in symptoms and multiple areas of consolidation or diffuse nodular opacities on chest radiograph and CT scan (see Figs. 6.2 and 6.3). Disseminated disease with a miliary or diffuse reticulonodular pattern occurs mainly in immunocompromised patients (6,7).

encapsulated focus of necrotizing granulomatous inflammation that develops in the same manner as the Ghon focus of tuberculosis. Nodules that have been present for more than a few months frequently show central (target) or diffuse calcification as a result of dystrophic calcification of the necrotic material (see Fig. 6.1). Calcified nodules are frequently associated with calcified hilar and mediastinal lymph nodes (6). The scenarios described in the preceding text are often unassociated with a clear history of exposure to a source of infection. Exposure to a relatively large number of organisms, such as during excavation of a contaminated work site or while exploring contaminated caves, may result in symptoms and multiple areas of consolidation or diffuse nodular opacities on chest radiograph and CT scan (see Figs. 6.2 and 6.3). Disseminated disease with a miliary or diffuse reticulonodular pattern occurs mainly in immunocompromised patients (6,7).

TABLE 6.1 Histoplasmosis | |

|---|---|

|

Chronic histoplasmosis is an uncommon manifestation of this disease, being seen in approximately 1 of 2,000 exposed individuals (1). It occurs almost exclusively in patients with chronic obstructive lung disease and results in chronic upper lobe consolidation, often with cavitation, resembling tuberculosis (see Fig. 6.4). Like the latter condition, healing frequently results in upper lobe scarring,

volume loss, and pleural thickening. Calcification of hilar and mediastinal nodes is commonly seen. The nodes may erode into the lumen of adjacent bronchi and result in broncholithiasis (6,7).

volume loss, and pleural thickening. Calcification of hilar and mediastinal nodes is commonly seen. The nodes may erode into the lumen of adjacent bronchi and result in broncholithiasis (6,7).

Mediastinal lymph node involvement may occur in any form of histoplasmosis. Such nodes may be enlarged or normal in size and are usually well circumscribed. In some patients, however, the inflammatory process extends into the adjacent mediastinum, resulting in fibrosing mediastinitis. Histologic examination in such cases shows dense fibrous tissue containing variable numbers of mononuclear inflammatory cells and granulomas. Organisms may be difficult to identify. The typical radiologic manifestation consists of a focal paratracheal mass of calcified lymph nodes frequently associated with partial or complete obstruction of the superior vena cava (6,7).

Coccidioidomycosis

Coccidioidomycosis is caused by inhalation of spores of the dimorphic fungus Coccidioides immitis. It is endemic in southwestern United States and northern Mexico. Several patterns of this disease can be seen (see Table 6.2). Acute (primary) infection results in bronchopneumonia, initially associated with a predominantly neutrophilic exudate and subsequently with granulomatous inflammation. In most patients, the reaction is mild and the radiograph is normal. Approximately 40% of patients are symptomatic and have

patchy areas of consolidation evident on the radiograph (see Fig. 6.5). Associated hilar lymph node enlargement is seen in 20% of cases. The consolidation usually resolves over several weeks (8).

patchy areas of consolidation evident on the radiograph (see Fig. 6.5). Associated hilar lymph node enlargement is seen in 20% of cases. The consolidation usually resolves over several weeks (8).

TABLE 6.2 Coccidioidomycosis | |

|---|---|

|

Chronic pulmonary coccidioidomycosis is radiologically characterized by nodules or cavities (see Figs. 6.6 and 6.7). Most are discovered incidentally in asymptomatic patients; approximately 25% can be seen to result from incomplete resolution of acute bronchopneumonia (see Fig. 6.8). In most patients the nodules or cavities are solitary and measure 2 to 4 cm in diameter. They may be thin walled (“grape skin”) or thick walled (8) and usually have homogeneous attenuation on CT scan (9). Histologically, the lesions correspond to foci of necrotizing granulomatous inflammation. Although sharply delimited by a well-developed fibrous capsule most often, inflammation surrounding the necrotic tissue can result in adjacent ill-defined areas of consolidation (9).

This disease is rarely progressive but occasionally may result in unilateral or bilateral upper lobe consolidation, sometimes associated with single or multiple cavities, resembling reactivation tuberculosis. Disseminated disease

is most commonly seen in immunocompromised patients and is usually manifested radiologically as a diffuse reticulonodular pattern or miliary nodules.

is most commonly seen in immunocompromised patients and is usually manifested radiologically as a diffuse reticulonodular pattern or miliary nodules.

Blastomycosis

Blastomycosis is caused by the dimorphic fungus Blastomyces dermatitidis. The disease occurs most commonly in the central and southeastern United States (endemic areas include the Ohio, Mississippi, and Missouri river valleys, particularly in Wisconsin) and southern Canada (mainly Quebec, Ontario, and Manitoba) (1). Patients with the disease usually present with symptoms of acute pneumonia, including abrupt onset of fever, chills, productive cough, and pleuritic chest pain. Arthralgias and myalgias are common and erythema nodosum develops occasionally.

The most common radiographic findings consist of acute airspace consolidation, observed in 25% to 75% of patients (see Table 6.3 and Fig. 6.9). The consolidation is patchy or confluent and may be subsegmental, segmental, or nonsegmental (10,11,12). Cavitation may be seen in up to 50% of patients with airspace consolidation (11). The second most common presentation, observed in approximately 30% of patients, is solitary or multiple masses (see Fig. 6.10). Clinically overwhelming infection may result in miliary dissemination. Pleural effusion is present in 10% to 15% of patients. Hilar or mediastinal lymph node enlargement is relatively uncommon. There is poor correlation between the radiologic abnormalities and the clinical presentation (10,12).

TABLE 6.3 Blastomycosis | |

|---|---|

|

Paracoccidioidomycosis (South American Blastomycosis)

Paracoccidioidomycosis (South American blastomycosis) is caused by the dimorphic fungus Paracoccidioides brasiliensis. The disease is found throughout South and Central America including Mexico (3). South American blastomycosis is seen more frequently in men, and most patients range from 25 to 45 years in age. The infection usually occurs in farmers, manual laborers, and other workers engaged in rural occupations and is probably caused by inhalation, which results in primary pneumonia and secondary systemic dissemination. Animal-to-human transmission and person-to-person transmission have not been documented. The disease is usually asymptomatic but can progress to severe pulmonary involvement, leading to cough and shortness of breath. Active pulmonary involvement and residual fibrotic lesions are observed in 80% and 60%, respectively, of patients with the disease. The lungs are the main target organ and the main cause of morbidity and mortality in these patients (13,14).

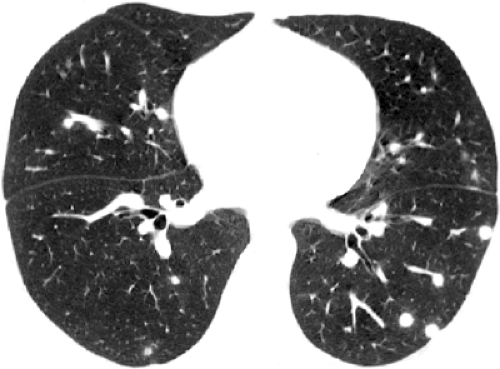

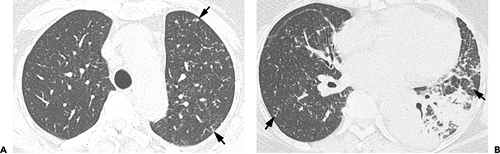

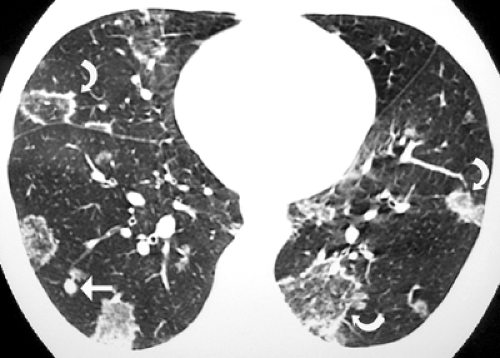

In the primary form of the disease, transient airspace consolidation may be seen in the middle lung zone. The most common radiologic manifestation consists of single or multiple nodules (paracoccidioidomas) that may be single or multiple (see Table 6.4). Progressive pulmonary disease may resemble tuberculosis; however, the lower lobes are more frequently involved than the upper lobes, and cavitations are less common. Hilar

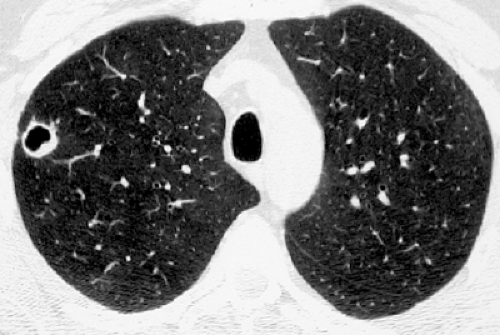

lymph node enlargement can occur by itself or in association with parenchymal involvement. High-resolution CT scan findings consist of multiple variable-sized nodules, cavitation, centrilobular opacities, peribronchovascular interstitial thickening, intralobular lines, and traction bronchiectasis (see Fig. 6.11). These abnormalities are usually bilateral and symmetric (15). A reversed CT halo sign (central ground-glass opacity surrounded by a crescent or ring of consolidation) is seen in 10% of patients with active P. brasiliensis infection (see Fig. 6.12) (16). The areas of ground-glass opacity in these patients correspond to the presence of inflammatory infiltrates in the alveolar

septa, and the peripheral consolidation reflects the presence of areas of intra-alveolar inflammatory infiltrates without organizing pneumonia (16).

lymph node enlargement can occur by itself or in association with parenchymal involvement. High-resolution CT scan findings consist of multiple variable-sized nodules, cavitation, centrilobular opacities, peribronchovascular interstitial thickening, intralobular lines, and traction bronchiectasis (see Fig. 6.11). These abnormalities are usually bilateral and symmetric (15). A reversed CT halo sign (central ground-glass opacity surrounded by a crescent or ring of consolidation) is seen in 10% of patients with active P. brasiliensis infection (see Fig. 6.12) (16). The areas of ground-glass opacity in these patients correspond to the presence of inflammatory infiltrates in the alveolar

septa, and the peripheral consolidation reflects the presence of areas of intra-alveolar inflammatory infiltrates without organizing pneumonia (16).

TABLE 6.4 Paracoccidioidomycosis | |

|---|---|

|

Cryptococcosis

Cryptococcosis is caused by Cryptococcus neoformans, which is commonly distributed in soil, especially that containing pigeon and avian droppings. Infection is acquired by inhaling spores of fungus. The lungs, central nervous system, blood, skin, bone, joints, and prostate are the most commonly involved sites.

Cryptococcosis occurs predominantly in immunocompromised patients (17) but can also be seen in the normal host. The incidence in the United States increased considerably in the 1980s in relation to the AIDS epidemic but decreased after 1990, before highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) became available, and further thereafter (17). Although cryptococcosis and other opportunistic fungal infections in persons with AIDS are no longer a major problem in developed countries, they are a major cause of morbidity and mortality in developing countries (4).

The spectrum of pulmonary cryptococcosis depends on the host’s defenses. In the immunocompetent host, cryptococcal infections are commonly localized to the lung and the patients are asymptomatic. In the immunocompromised patient, cryptococcal infections often cause symptomatic pulmonary infections and often disseminate to the central nervous system, skin, and bones.

Approximately one third of patients are asymptomatic. Symptoms range from mild cough and low-grade fever to acute presentation with high fever and severe shortness of breath. The disease can spread rapidly throughout the lungs and disseminate to extrapulmonary sites, especially the meninges in immunocompromised patients.

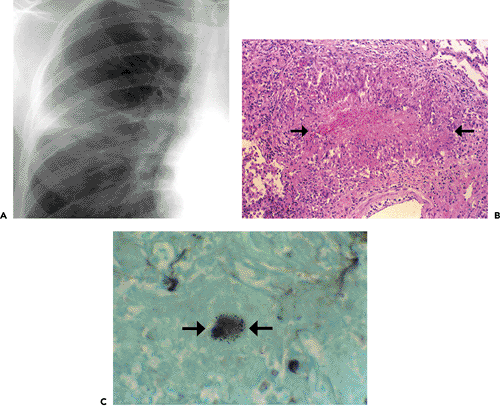

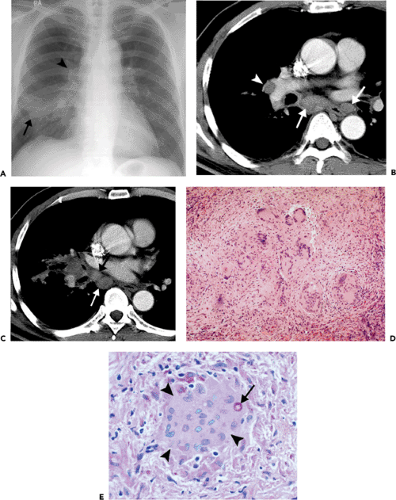

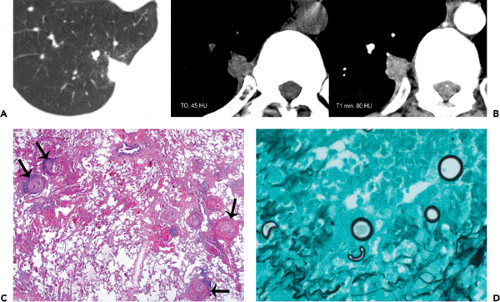

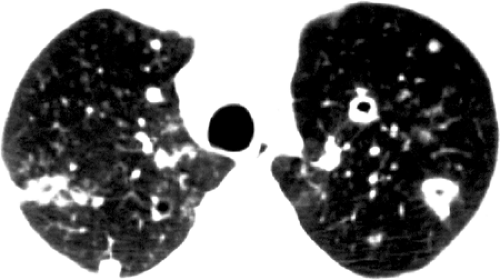

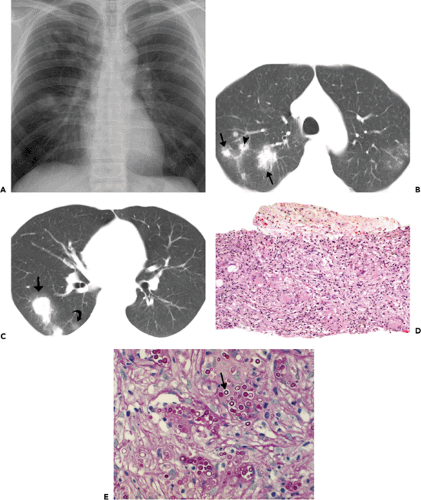

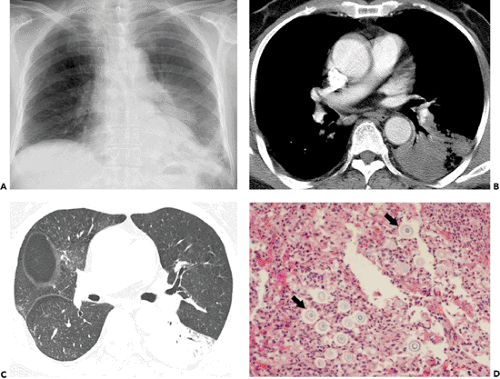

Histopathologically, immunocompetent patients show granulomatous response, such as noncaseating granulomas or extensive caseation. In immunocompromised patients, intact alveolar spaces become filled with yeasts. The radiologic findings include solitary or multiple nodular opacities (see Fig. 6.13), segmental or lobar consolidation (see Fig. 6.14), hilar and mediastinal lymphadenopathy, and pleural effusion (see Table 6.5). Cavitation is seen in approximately 10% to 15% of cases (18,19,20). The radiologic manifestations are influenced by the patient’s age and immune status. Immunocompetent patients tend to present with nodules or masses (18,19,21), younger patients are more likely to present with cavitation (18), and immunocompromised patients are more likely to have airspace consolidation, lymphadenopathy, pleural effusion, and disseminated disease (22,23,24).

Figure 6.14 Cryptococcosis. A: Chest radiograph shows mass-like consolidation in left lower lobe. B: Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) image (5-mm collimation) obtained at the level of the right middle lobe bronchus shows left lower lobe consolidation. C: Lung window image of high-resolution CT scan (1-mm collimation) obtained at similar level to (B) demonstrates consolidation and air bronchograms in left lower lobe. Also note ground-glass opacities in right upper lobe. D: Photomicrograph of the transbronchial lung biopsy specimen shows acute inflammation and many cryptococci (arrows) with wide unstained capsules. The patient was a 74-year-old man.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|