“In our instruction, we have tried to emphasize that a manuscript can be grammatically and semantically perfect and still be worthless if it is not scientifically valid. So we stress, first, clinical reasoning and analysis of experimental design and data, scientific validity, logical organization, and coherent development, and only then attention to the prose – grammar, semantics, conciseness, lucidity, readability, style.” — Selma and Lois DeBakey

Qualifications for Preparing a Manuscript on Writing, Reviewing, and Editing

Before describing some aspects of writing, reviewing, and editing medical manuscripts, it seems reasonable to give my qualifications for doing so. Since my first publication in a peer-reviewed medical journal in 1961, I have subsequently authored a number of articles each year. I have been editor in chief of The American Journal of Cardiology ( AJC ) since June 1982 and of The Baylor University Medical Center (BUMC) Proceedings since 1994. During these 30 years with the AJC , 61,000 manuscripts have passed across my desk, and during the 17 years with the BUMC Proceedings , 1,500 manuscripts. As editor, I have tried to put my stamp, so to speak, on the editorial pages of both journals: by writing periodic editorials in one ( AJC ) and a column (Facts and Ideas from Anywhere) in the other ( BUMC Proceedings ). I have written a number of editorials on writing and editing, and several of these will be highlighted in the remainder of this piece.

Formulating an Answerable Question

When considering a potential clinical topic for investigation and later publication in a medical journal, the first step is to formulate a precise question which is answerable. Sometimes it takes considerable thought to formulate the question properly. The key is to have something to report. Does the message add to the present knowledge base, or does it simply confirm a previous observation or describe it better than before?

Formulating an Answerable Question

When considering a potential clinical topic for investigation and later publication in a medical journal, the first step is to formulate a precise question which is answerable. Sometimes it takes considerable thought to formulate the question properly. The key is to have something to report. Does the message add to the present knowledge base, or does it simply confirm a previous observation or describe it better than before?

Order of Manuscript Preparation

Every author probably creates a manuscript a bit differently. First, I prepare the tables and figures and try to make them final before a single word of the manuscript is written. Next, I write the title . Next, the abstract (summary); writing it early on forces me to focus on the manuscript’s important points. Then, during each revision, the abstract can be tweaked a bit. Next is the introduction , which I try to make a single paragraph that provides specifically the purpose of the manuscript. Then the methods and results , which should be in exquisite detail. These 2 sections are the heart of the manuscript. Some journals put these in a smaller font than that used in other portions of the manuscript. That move is not logical, in my view. If anything, the methods and results should be in a larger font than the rest of the manuscript. Then the discussion , which, in essence, focuses on how the results should be interpreted. Finally, the references ; their selection, accuracy of recording, and formulation according to the style of the journal are clues to the scholarship of the authors.

Preparing the Tables

Tables 1 and 2 are good examples. Table 1 summarizes data in several large multicenter studies, and there is only 1 line across per study. Tables with a lot of words in them usually are unsatisfactory. Table 2 illustrates a study involving a limited number of patients. This table shows how each patient receives only 1 line across. If the number of patients studied is ≤30, individual patient data can be provided. There should be some logical order for listing the patients, such as by increasing age or order of the figures, as done in Table 2 . I prefer to spell out the variables (parameters) to be analyzed. It is better to put the percent sign after the number rather than in the variable column. The units of measurement in the variable column are best placed in parentheses. Vertical lines are best avoided.

| Events | Mean LDL-C (mg/dl) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients | Control | Relative Risk Reduction | Patients | Controls | ||||||||||

| Study | Year | Journal | Subjects | Diagnosis | Age (yrs) | Length of Study (yrs) | Agents Comparison | Baseline | End | Baseline | End | |||

| MIRACL | 2001 | JAMA | 3,086 | ACS | Mean 65 | 0.31 | A 80 vs P | 14.80% | 17.40% | ↓ 16% | 124 | 72 | 124 | 135 |

| HPS | 2002 | Lancet | 20,526 | CAD, PVD, DM | 40–80 | 5 | S 40 vs P | 7.60% | 9.10% | ↓ 17% | 131 | 90 | 131 | 129 |

| ASCOT-LLA | 2003 | Lancet | 10,305 | SH | 40–79 | Median 3.3 ⁎ | A 10 vs P | 1.90% | 3.00% | ↓ 31% | 133 | 90 | 133 | 126 |

| PROVE-IT | 2004 | NEJM | 4,162 | ACS | Mean 58 | Mean 2 | A 80 vs PRA 40 | 19.70% | 22.30% | ↓ 14% | 106 | 62 | 106 | 95 |

| CARDS | 2004 | Lancet | 3,838 | DM | 40–75 | Median 3.9 ? | A 10 vs P | 9.40% | 13.40% | ↓ 37% | 117 | 81 | 117 | 120 |

| A to Z | 2004 | JAMA | 4,497 | ACS | Mean 61 | 0.5–2 | S 40 to S 80 vs P to S 20 | 14.40% | 16.70% | ↓ 11% † | 112 | 66 | 111 | 81 |

| TNT | 2005 | NEJM | 10,001 | CAD, PVD | Mean 61 | Median 4.9 | A 80 vs A 10 | 8.70% | 10.90% | ↓ 22% | 97 | 77 | 98 | 97 |

| IDEAL | 2005 | JAMA | 8,888 | MI | <80 | Median 4.8 | A 80 vs S 20 | 9.3% ? | 10.4% ? | ↓ 11% † | 122 | 81 | 121 | 104 |

| SPARCL | 2006 | NEJM | 4,731 | Stroke, TIA | Mean 63 | Median 4.9 | A 80 vs P | 11.20% | 13.10% | ↓ 16% | 133 | 43 | 134 | 129 |

| SEAS | 2008 | NEJM | 1,873 | AS | Mean 67 | Median 4.3 | S 40 + E 10 vs P | 35.30% | 38.20% | ↓ 9% † | 140 | 75 | 139 | 134 |

| JUPITER | 2008 | NEJM | 17,802 | Healthy | Mean 66 | Median 1.9 ? | R 20 vs P | 0.02% | 0.03% | ↓ 47% | 108 | 55 | 108 | 109 |

⁎ Stopped early – Study planned for 5 years.

| Case No. (Fig. No.) | Age (years) | Sex | AVR to Discharge (days) | AVR to Death (days) | CABG | AS | AR | MS | MR | IE | RHD | IMR | MVP | MAC | Pre-op AF | BMI (kg/m 2 ) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (2) | 53 | F | 5 | Alive (5264) | 0 | + | 0 | + | 0 | 0 | + | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 34 |

| 2 | 50 | M | 9 | 3704 | + | + | 0 | + | 0 | 0 | + | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 † | 27 |

| 3 (3) | 46 | M | 4 | 2534 | 0 ⁎ | + | 0 | + | 0 | 0 | + | 0 | 0 | 0 | + | 26 |

| 4 (4) | 74 | F | 13 | 4856 | 0 | + | 0 | + | 0 | 0 | + | 0 | 0 | 0 | + | 21 |

| 5 (5) | 71 | M | 12 | Alive (1162) | + | + | 0 | + | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | + | 0 | 35 |

| 6 (6) | 84 | F | 18 | 3858 | + | + | 0 | 0 | + | 0 | 0 | + | 0 | 0 | 0 | 29 |

| 7 (7) | 77 | M | 7 | 867 | + | + | 0 | 0 | + | 0 | 0 | + | 0 | 0 | 0 † | 22 |

| 8 (8) | 58 | F | 6 | Alive (1301) | 0 | + | 0 | 0 | + | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 42 |

| 9 (9) | 68 | M | 6 | 1540 | 0 | + | 0 | 0 | + | 0 | 0 | 0 | + | 0 | 0 | 23 |

| 10 (10) | 67 | M | 6 | Alive (1267) | 0 | + | 0 | 0 | + | 0 | 0 | 0 | + | 0 | 0 † | 24 |

| 11 (11) | 66 | M | 7 | 472 | 0 | + | 0 | 0 | + | 0 | 0 | 0 | + | 0 | 0 | 27 |

| 12 | 48 | M | 56 | Alive (6096) | + | 0 | + | 0 | + | 0 | 0 | 0 | + | 0 | + | − |

| 13 (12) | 66 | M | 6 | Alive (1252) | 0 | 0 | + | 0 | + | + | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 23 |

| 14 (13) | 47 | M | 5 | 674 | 0 | 0 | + | 0 | + | + | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 36 |

| 15 | 24 | M | 14 | Alive (2017) | 0 | 0 | + | 0 | + | + | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 20 |

| 16 (14) | 50 | M | 11 | Alive (1127) | 0 | 0 | + | 0 | + | + | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 23 |

⁎ Previous resection of aortic isthmus coarctation.

† Developed atrial fibrillation postoperatively after double valve replacement.

Finding the Masterful Figure

When examining a new manuscript (or a published article), after reading the title, the authors’ names, and abstract, I immediately go to the figures, seeking the one figure that provides the message of the manuscript. With my own publications, I spend more time in developing the figures and tables than I do in writing the manuscripts. I believe that the graphic or tabular presentation of the data carries more impact than the written text, which in essence simply describes the findings and interpretations of the graphs and figures.

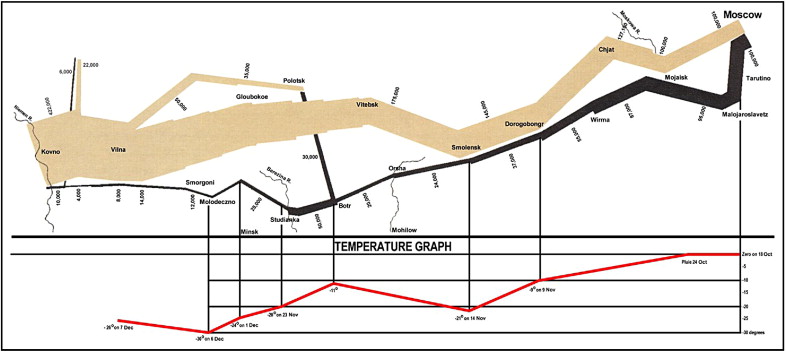

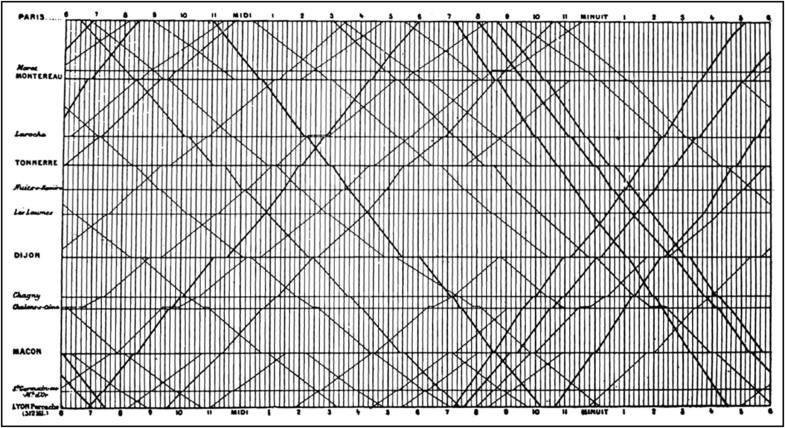

I was pleased years ago to acquire Edward R. Tufte’s Visual Display of Quantitative Information (Graphics Press, Cheshire, Connecticut, 1983). Contained in the 187-page book are numerous data graphics that display measured quantities by combined use of points, lines, coordinates, numbers, symbols, shading, sometimes color, and a few words. As pointed out by Tufte, the use of abstract pictures to statistical graphics—length and area to show quantity, time series, scatter plots, and multivariant displays—was not invented until 1750 to 1800, long after logarithms, Cartesian coordinates, calculus, and the basics of probability theory. As Tufte emphasized, modern data graphics do much more than simply substitute for statistical tables. They serve as instruments for reasoning about quantitative information. Often the most effective way to describe, explore, and summarize a set of numbers is to look at pictures. Of methods for analyzing and communicating statistical information, well-designed data graphics usually are the simplest and most powerful. According to Tufte, who presently is professor emeritus of political science and statistics and computer science at Yale University, each year somewhere between 900 billion and 2,000 billion images of statistical graphics are published, and some of them appear in cardiology journals. Two of Tufte’s graphics are illustrated in Figures 1 and 2 . Each of these graphics tells a huge story in a very simplified but sophisticated manner (see legends).

The Article’s Title

Although it is the most frequently read part of a manuscript, the title too often is given too little attention by authors. Whenever I write an article, the first words put on paper are those of the article’s title. Then, with each revision of the manuscript, the title is carefully reexamined and usually reworded such that it is changed several times before the final typing of the manuscript. Focusing on the title requires careful focusing on the actual contents of the manuscript, because the title should be a precise description of those contents. I change the titles of most AJC manuscripts returned to authors for response to comments of reviewers and editors. The change in some may be the deletion or addition of only 1 or 2 words; in others, the change may be extensive.

What constitutes a good title? Above all, the title should be descriptive of the manuscript’s contents. This description should not be in general terms but in as specific and precise terms as possible. The title should be devoid of excessive words but sufficient in words to adequately describe the manuscript’s contents. The title should have a smooth flow. The message of the manuscript should not be in the title, which ideally should arouse the reader’s curiosity so that he or she will go past it into the manuscript’s text. If the manuscript’s message is in the title, the curiosity may be immediately satisfied and the next article then sought. Subtitles should be avoided. Subtitles often are more specific than the main title, and therefore, they deserve to be the main title or at least incorporated into the main title. A minor factor against use of subtitles is that they often are omitted when the article is later referenced. Titles of experimental studies should include the animal species when the manuscript involves nonhuman animals. Titles as questions should be avoided. Abbreviations in titles should be avoided. Occasionally, the use of italics for 1 or 2 words in a title provides useful emphasis. Cardiologic titles are of many types, but common recurring ones include comparison of … , usefulness of … , association of … , effect of … , efficacy of … , evaluation of … , importance of … , influence of … , limitations of … , relation of … , results of … , analysis of … , and value of … .

The Abstract: The Manuscript’s Bottom Line

After the title, the next most frequently read portion of the manuscript is the summary (abstract). But is the summary given the same attention by authors as that given by readers? I think not. The summary, I suspect, tends to be written by many authors just before the final typing of the manuscript. Thus, when written last, the summary tends to be disjointed, as it attempts to tie together the important points of the paper. When written first, the summary serves as an outline. Moreover, by being done last, the summary may not receive the thoughtful deliberation given other portions of the manuscript.

Because the summary is so important to a manuscript, I suggest that an author write this portion first (after the title) rather than last. By doing so, one may focus better on the number of points the particular manuscript is trying to make. If the manuscript has essentially only 1 point, the summary can be particularly crisp and short; if >1 point, it serves as an outline of the points to be made. After the point or points of the manuscript are clearly in focus, the remainder of the paper can more readily build a case to demonstrate the validity of each point. The summary needs to be given the same emphasis and importance by authors as it receives from readers.

The Discussion

This is the only portion of the manuscript that I outline before writing. In general, the first paragraph provides a brief summary of the major finding, and then a discussion of previous publications on the same topic including what is different about the present study compared to previous publications. Does the present study provide new information or simply confirm that provided by previous publications? Then some comments on the strengths and limitations of the present study. A summary at the end of the discussion is usually unnecessary.

The References

References are an important part of a manuscript. Their selection is an indicator of the authors’ knowledge of and regard for work preceding their own, and their accuracy of recording is a clue to the quality of the authors’ own work. Some authors tend to support statements in their manuscripts by multiple references, but often when this is done, some references do not support the statement for which they are being used. Other authors provide few references and open themselves to criticism for not giving sufficient credit to their predecessors. Should the initial or latest work on the subject be cited, or simply the present authors’ previous work on the subject? A middle course between “too many” and “too few” references appears most reasonable. In the AJC , the number of references, except in reviews, is generally limited to ≤30.

An occasional criticism by reviewers of manuscripts is that their work was not cited. Accordingly, the reviewer may feel slighted and may react by being overcritical. References to an individual increase the chances, however, that that person will be selected to review the manuscript in question. I certainly look at the references cited when deciding to whom to send a manuscript for review. When reading a published or unpublished paper on which they too have contributed information, many authors and readers review the list of references cited. I am reminded of a story regarding 2 prominent authors. The late William F. Buckley, Jr. , and John Kenneth Galbraith habitually exchanged their most recently published books with each other. Galbraith upon receiving Buckley’s latest book immediately turned to the title page, anticipating a note from his friend. Finding none, Galbraith then turned to the references, and beside the first citation of one of Galbraith’s books, Buckley had written, “Hi, John, Bill.”

Some manuscripts contain too many references and too little data. That a publication has been read during the preparation of a manuscript is not justification for its being cited as a reference. References should be carefully selected, and they should support the statements or comments to which they are attributed. And, just as a good paragraph should have no unnecessary sentences and a good sentence no unnecessary words, a manuscript should have no unnecessary references. Each reference, like each paragraph or sentence, should have a meaningful purpose.

Many errors are made in recording references. Examine any 10 references in a medical journal, and usually at least 1, often more, will contain an error. I suspect that inaccurately recorded references are found most frequently in manuscripts containing inadequately recorded data. Therefore, both as an editor and a reader, I examine the references in manuscripts: names are often misspelled, initials preceding the last name are often wrong, and “Junior” or “III” occasionally is omitted; titles often are recorded inaccurately and subtitles are frequently omitted; volume numbers, page numbers, and year of publication may be erroneously recorded. A major source of errors in references is recording a reference listed in another publication without actually reading that publication. In this way, previous recording errors are propagated in subsequent publications.

The following procedures have proved useful to me in diminishing errors in recording references for my own manuscripts:

- 1

Each reference initially is recorded on a 3 × 5 inch card in print rather than script to prevent subsequent misinterpretation when typed. All authors, full title with subtitle, volume, inclusive page numbers, and month and year of publication are recorded on these cards. Recording both the month as well as the year of publication allows chronologic listing of references published in the same year on the same subject.

- 2

The senior or established author must check references recorded by young or relatively new investigators to ensure accuracy.

- 3

References are recorded only from the original publication. To cite a reference from a previously published reference list without checking the original publication is poor research. A medical publication should never be referenced without reading it!

- 4

References are typed only once, and that is in final form in the final manuscript directly from the 3 × 5 cards on which they are originally recorded. The cards are numbered in pencil in the order in which they appear. Having each reference on a separate card allows the author to change the order without altering the entire typed format.

- 5

The typed list of references is carefully proofed from the original 3 × 5 cards by the recorder of the references on the cards. This person can read his or her handwriting better than anyone else. More typographic errors are made in typing references than any other portion of a manuscript. Therefore, the single typing of references from the original reference cards prevents errors which occur from multiple typing.

- 6

The references in the galley proofs are checked against the original 3 × 5 reference cards.

References listed in the AJC and in the BUMC Proceedings are complete in that the names of all authors, subtitles as well as primary titles, and inclusive page numbers are required. References submitted to these 2 journals in another format suggest that the manuscript has been submitted previously to another journal, which rejected it, or that the authors are not sensitive students of medical publications. With text pages at a premium, why are all authors, all titles, and inclusive page numbers required in the AJC and BUMC Proceedings ? By listing all authors, all titles, and inclusive page numbers (rather than just the first page number of the article), the authors of the manuscript are virtually required to check the original article, and this checking increases the likelihood that the entire reference is recorded accurately. Supplying all authors’ names assists an editor in the selection of possible manuscript reviewers. (The last author is likely to be a member of the journal’s editorial board or more prominent than is the first author.) Listing inclusive page numbers prevents confusion of a reference to a previously published manuscript versus one to an abstract, which is virtually never >1 page. To diminish the space occupied by references without diminishing their accuracy or usefulness, the font size utilized for references in both the AJC and the BUMC Proceedings is small.

The method just described is a bit old fashioned in our present high-tech era. EndNote, a software program setup specifically for organizing references, is used by many investigators today.

In summary, references are a reflection of a manuscript’s quality and should be selected carefully, recorded accurately, and prepared in the style of the journal to which the manuscript is submitted.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree