Femoropopliteal Bypass Using Prosthetic and Vein

Neal Barshes

The accepted indications for revascularization in the setting of femoropopliteal segment occlusive disease remain the same as they have been for decades, namely femoropopliteal disease associated with: (1) nonhealing foot wound (including foot ulcer or gangrene), (2) foot or leg pain at rest that appears to be due to an ischemic etiology, or (3) severe claudication that is both limiting in one’s daily activities and recalcitrant to supervised exercise regimen. In most contemporary vascular surgical practices, an attempt at endovascular intervention is usually the first-line option for patients meeting the above criteria, and surgical bypass is reserved for cases that cannot be successfully treated with percutaneous endovascular techniques. Proceeding directly to open surgical bypass is a perfectly valid treatment option, however, in cases that are unlikely to have an effective or durable response to endovascular intervention—for example, young patients with long-segment occlusion of the superficial femoral artery, good-caliber ipsilateral saphenous vein, and debilitating claudication. So, although the indications for revascularization have remained unchanged, the ultimate decision between endovascular intervention and femoropopliteal bypass requires judgment based on both the clinical situation and one’s own technical experience and expertise.

Once the decision for femoropopliteal bypass has been made, the surgeon has three main tasks: (1) Delineation of the arterial anatomy (i.e., identifying the source of proximal inflow and the distal target), (2) identification of optimal conduit options, and (3) risk stratification and ensuring medical optimization.

Delineation of Arterial Anatomy

Digital subtraction angiography (DSA) still remains the standard preoperative imaging modality for patients with femoropopliteal occlusive disease who are being considered

for surgical revascularization. In contemporary practice many patients may have this performed as part of an attempted endovascular intervention; if this is not the case, DSA for purely diagnostic purposes should be considered as it provides a level of resolution/anatomic detail that still remains unrivaled. An appropriate popliteal distal target will have the following qualities on DSA:

for surgical revascularization. In contemporary practice many patients may have this performed as part of an attempted endovascular intervention; if this is not the case, DSA for purely diagnostic purposes should be considered as it provides a level of resolution/anatomic detail that still remains unrivaled. An appropriate popliteal distal target will have the following qualities on DSA:

Provides in-line flow to at least the ankle

No significant atherosclerotic disease

Although computed tomography with angiography (CTA) is a noninvasive alternative that can provide anatomic imaging with good resolution, the assessment of popliteal- and tibial-level atherosclerotic disease can be limited by spatial resolution as well as by artifact caused by concentric calcification of the media layer of the arterial wall. In addition, it requires much larger contrast doses than DSA (typically 120 mL or more versus ∼40 mL, respectively). Magnetic resonance arteriography (MRA) is another noninvasive alternative, but commonly overestimates the degree of stenosis in arteries.

Conduit Planning

The optimal conduit for femoropopliteal bypass—to both the above-knee and the below-knee segments of the popliteal artery—is undoubtedly good-caliber single segment autogenous vein. There are three very strong reasons for this:

Patency is better

The consequences of failure are less problematic

Risk of graft infection is virtually nil

The ipsilateral greater saphenous vein would be the obvious first choice for this conduit if ultrasound imaging or intraoperative assessments demonstrate that this is good caliber (generally at least 3.5 mm in diameter in vivo or at least 2.5 mm on ultrasound) throughout the length needed for the bypass. If the ipsilateral saphenous vein is absent or atretic, the contralateral greater saphenous vein would typically be the next best alternative for patients in whom the adequate caliber ipsilateral greater saphenous vein is not present. Careful decision-making is needed in patients without adequate ipsilateral or contralateral greater saphenous vein conduit. Arm vein and lesser (small) saphenous vein can be good alternatives if adequate caliber and good length are present, though multiple segments (i.e., splicing) are necessary to reach a below-knee popliteal target. Although these require alternative autologous vein conduits require longer operative times, additional incisions and more frequent postoperative intervention, their clinical outcomes are generally better than that of prosthetic conduits.

Polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) conduit has a role when autologous conduit is not a good option. If PTFE is to be used, 6- or 8-mm ringed PTFE should be the standard choice. There is some evidence to suggest heparin-bonded ePTFE has an advantage over PTFE. Distal vein cuffs probably do not provide benefit for the above-knee popliteal artery but may improve the patency of distal anastomoses to the below-knee popliteal artery. Cryopreserved venous and arterial allografts have dismal poor long-term patency, so its role as a conduit for femoropopliteal bypass should probably be limited to use in patients who merit revascularization for healing of a foot wound (especially if infected) and who have no other reasonable conduit options.

Risk Stratification and Medical Optimization

Risk stratification should be done according to standard consensus recommendations or according to local multidisciplinary consensus guidelines. Patients with active cardiac conditions, including unstable angina, severe exertional angina, decompensated heart failure, severe valvular disorders, ventricular arrhythmias, or myocardial infarct within 30 days should generally undergo coronary angiography. Patients who can achieve less than 4 metabolic equivalents of task and have three or more minor predictors (ischemic heart disease, history of stroke, compensated heart failure, diabetes mellitus, or chronic

kidney disease) should generally undergo some type of noninvasive cardiac evaluation (stress EKG, dobutamine echocardiogram, or nuclear myocardial perfusion scan with stress) before going to the operating room.

kidney disease) should generally undergo some type of noninvasive cardiac evaluation (stress EKG, dobutamine echocardiogram, or nuclear myocardial perfusion scan with stress) before going to the operating room.

Preparation on the Day of Surgery

Surgeons familiar with the performance of duplex ultrasound examinations should evaluate the ipsilateral greater saphenous vein and mark its course on the morning of surgery, preferably before the patient enters the operating room. This practice not only allows the surgeon to confirm the presence and adequacy of an adequate venous conduit option but also has been shown to decrease wound infection rates, perhaps through the avoidance of asymmetric or thinned soft tissue flaps, creation of dead space, etc.

Preparation and Positioning in the Operating Room

Once in the operating room the patient is placed on a fluoroscopy-compatible operating room table with the pedestal of the bed centered under the chest or upper abdomen (i.e., not under the lower extremities). Once the anesthetic of choice (general or regional) has been administered, the patient is placed in supine position for the operation. If the surgeon is confident that adequate saphenous vein is present, one or both arms can be padded and tucked alongside the torso. One or both arms should be secured on arm boards (and possibly prepared and draped a priori) if there is a possible (or high) likelihood that arm vein will be needed.

A Foley catheter should be placed. Two electrocautery grounding pads should be placed if two operative surgeons work simultaneously. Hair clippers should be used to remove hair in all areas that will be prepared and draped in the surgical field. At minimum, this field includes the lower abdomen (level of the umbilicus and below), the ipsilateral groin, and the circumferential surface of the ipsilateral lower extremity in its entirety (i.e., from the upper thigh to the toes). Obviously, the contralateral lower extremity and/or one or both arms may also be prepared if these sites may be needed for autologous vein harvesting. Isopropyl alcohol solution may be used on gauze dressings to perform a preliminary cleansing and sterilization of the operative fields; this should then be followed by ChloraPrep (isopropyl alcohol/chlorhexidine gluconate solution) over all intact skin surfaces. Betadine/iodine solution may be needed on the foot if an open wound or ulcer is present. Draping is done as in other areas using towels at the margins of the prepared/unprepared skin surfaces; generally, two U-shaped drapes work best to isolated the prepared field. A stockinette or isolation bag is used to cover the foot. Use of Ioban antimicrobial adhesive drapes may also be considered to further reduce the risk of wound infection.

Vein Harvesting

Beginning the operation with exposure of the vein conduit is advantageous for two main reasons. First, it is the ultimate assessment to ensure that the vein is indeed adequate in caliber and length for bypass. Finding that the intended autologous vein conduit is inadequate allows the surgical team to move toward investigating second-line options or forgoing vein harvesting in favor of a prosthetic conduit earlier in the case. Second, if identified and protected, exposure of the vein will minimize the risk of inadvertent injury to it while exposing the popliteal artery or creating tunnels (see below).

Vein harvesting should begin with an incision in the thigh. As stated above, the surgeon familiar with bedside duplex ultrasonography can direct incision immediately over the greater saphenous vein if a skin marker has been used to identify the course. Otherwise, the surgeon should start in the proximal to mid-thigh, where the greater

saphenous vein typically courses medially and posteriorly before passing along the posteromedial aspect of the knee. The edges of the skin incision should only be retracted with toothed forceps or self-retaining retractors; Debakey or other smooth-tip (e.g., vascular) forceps should never be used on the skin edges. Metzenbaum scissors should be used to spread or sharply cut the dermis and subcuticular adipose tissue until the saphenous vein is clearly identified. Electrocautery use should be minimized or avoided altogether to avoid thermal injury to the vein-–injury which may not be recognized at the time of the harvest.

saphenous vein typically courses medially and posteriorly before passing along the posteromedial aspect of the knee. The edges of the skin incision should only be retracted with toothed forceps or self-retaining retractors; Debakey or other smooth-tip (e.g., vascular) forceps should never be used on the skin edges. Metzenbaum scissors should be used to spread or sharply cut the dermis and subcuticular adipose tissue until the saphenous vein is clearly identified. Electrocautery use should be minimized or avoided altogether to avoid thermal injury to the vein-–injury which may not be recognized at the time of the harvest.

The numerous trials and studies of endoscopic vein harvesting for both coronary and leg bypasses demonstrating the negative impact of this technique on graft patency have suggested that harvesting is an important factor in determining long-term outcomes. Thus, once the vein conduit is identified, the “no touch” technique of vein harvesting should be employed. Specifically, trauma to the vein conduit can be minimized by approaching the vein harvesting in two steps. First, the superficial-most aspect of the vein is exposed to identify the precise course of the vein and to examine its caliber. This is best done with Metzenbaum scissors, working from the proximal aspect of the thigh toward the calf. Either single incisions can be used in the thigh and calf with a skin bridge at the knee, or several shorter “skip” incisions can be used throughout the thigh and calf; no difference in outcome between these two strategies has been demonstrated. The vein should be exposed for 4 to 6 cm beyond the anticipated length needed to assure that the conduit will not be too short.

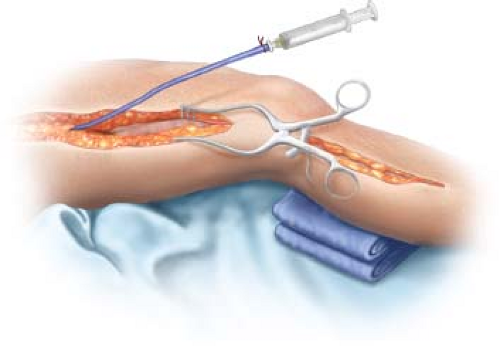

The second step can be completed after sufficient vein length has been exposed or after exposure of the arterial segments and tunneling (see below). The distal-most aspect of the exposed vein is clamped with a right ankle and sharply transected immediately proximal. The distal end is ligated with a silk or polyglactin (Vicryl) ligature, and a small metal or plastic cannula with an olive-shaped tip is inserted into the vein to distend the vein with a syringe filled with heparinized saline or physiologic vein solution. The tip of this cannula can be secured by the placement of a silk ligature at the distal-most end of the vein. The cannula and syringe can then be used to manipulate the vein and expose the vein branches to the surgeon or assistant on the other side of the table (Fig. 24.1). The distal aspect of the vein branches (the portion far from the main segment of the vein) can be ligated with a small (3-0 or 4-0) silk ligature or with small or medium metallic clips. The proximal aspect (i.e., that closest to the harvested vein conduit) should be ligated securely with a silk ligature approximately 1 to 2 mm from the lumen of the vein before dividing the branch to avoid constraining its caliber.

Throughout this process the harvested vein conduit should not be grasped with forceps or metal instruments. The cannula and syringe should be used for most of the manipulation of the vein that is necessary to expose and dissect branches. In the times when this does not suffice (e.g., when working just beyond a skin bridge), the vein can be gently retracted with vessel loop placed once around the artery.

Exposure of the Common Femoral Artery for Inflow

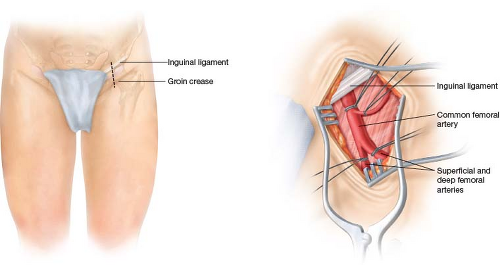

The common femoral artery should be exposed through an incision in the groin. If the surgeon is confident that there is not enough atherosclerotic disease in the femoral artery to merit an endarterectomy, profundaplasty, or patch angioplasty, a transverse or oblique incision can be used. Otherwise, a longitudinal incision is best, as this incision allows for the extension needed to expose the proximal superficial and deep femoral arteries should this prove necessary to address significant atherosclerotic disease there (Fig. 24.2).

Exposure of the Popliteal Artery as a Distal Target

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree