Chapter Five

Exploring the Root Causes

It is very clear that women with heart disease are not receiving the same care as men. We continue to fall short in diagnosis, testing and treatment of women with coronary artery disease (CAD). As mentioned previously, mortality rates for men continue to decline while those for women continue to stay the same (and in some cases increase slightly). In previous chapters we have considered the biological differences in disease presentation and progression. In addition, we have discussed the atypical symptoms that women often experience and the fact that some diagnostic tests are not as accurate in women. This makes diagnosis more challenging for even experienced providers with the best of intentions. Over the last several decades we have amassed a great deal of evidence for the best approach to treating acute myocardial infarction and unstable angina. Now, more than ever, we have multiple potentially life-saving therapies at our disposal when treating cardiac events. A review of the literature supports the fact that evidence-based therapies and clinical guidelines are not applied equally in men and women.

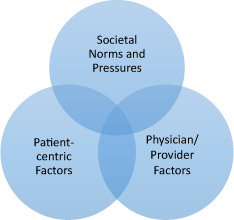

Figure 5.1 Factors affecting gender disparities in cardiovascular care.

Why exactly is this? What are the root causes for the phenomenon gender inequality? More importantly, what can we do about it?

In order to best answer these questions, we must first explore gender roles in the US and the UK — what they have been in the past, and how they are changing as our governments and economies evolve. The way in which society perceives individual genders may very well have a significant impact on how and why women receive different care when it comes to heart disease.

Television programs set in the 1950s and 1960s depicted the doting housewife, caring for the children at home while the man of the house goes off to work in his suit and tie. In the US today, the stereotypical 1950s housewife is a rare occurrence. In general, gender roles are norms that are defined by society — but this definition does not mean that these are the only acceptable roles. In the US and the UK, traditional gender roles have been associated with more aggression and dominance in men, and more passivity and nurturing behaviors in women. Things are changing — in a study released in May 2013 by the Pew Research Center, 40% of women were found to serve as the leading breadwinners for the family. This is in stark contrast to 11% in 1960. Of these breadwinner women, 40% are married and have higher incomes than their male spouses. Even with more women working outside the home, the traditional stereotypes of women as the primary homemaker places additional pressure and responsibilities on working mothers. In many cases, they continue to provide meals, assist with homework and provide most of the direct childcare and child management needs. Studies support the fact that women are the primary reason that other family members seek out healthcare. They ensure that appointments are made and attended for both children and spouse. Career-minded, successful women often find that there are not enough hours in the day to perform well in high-level jobs as well as excel as a wife and mother. Ultimately, something has to give — and often it is the busy mother’s health.

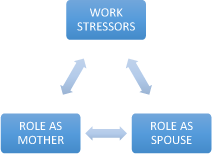

Studies have shown that working mothers with children at home experience more stress and actually secrete higher levels of cortisol as compared to unemployed women.1 This response is independent of whether they are married or not — having a spouse and working as a mom makes no difference in stress levels. Interestingly, the cortisol levels seemed to rise throughout the workday and no decline was seen once at home. Women have been found to have higher blood pressure as occupational status and work skill increases.2 Other investigations have documented differences in the ways in which stress hormones such as catecholamines rise and fall during the day for working women versus working men. In men in management positions, levels of epinephrine and norepinephrine were seen to peak during the workday and sharply decline once they arrived home.3 In contrast, female managers were found to have levels of catecholamines that increased throughout the workday and then continued to rise once arriving at home. Cortisol, and other catecholamines (stress hormones) are often associated with increased cardiovascular strain and cardiac events in those individuals with risk factors or who are predisposed to disease.

Figure 5.2 Cardiac stressors in women.

Stress levels alone at work are insufficient to explain the health consequences experienced by working women. It is more likely the complex interaction of multiple stressors related to the performance of multiple complex roles — work, wife and mother. Data from the Framingham database found a very strong correlation between CAD and employed women with multiple children.4 It is clear that women experience different stressors than men and the biological and psychological responses to these stressors can be quite variable. Moreover, coping with the challenges of multiple roles and the pressures of societal norms can be challenging. Gender disparities in care for heart disease may be due to a combination of factors; some physician/provider centric and others that are more patient centered. These “root causes” cannot easily be explained nor are they easily corrected.

Often, in situations where we see multi-factorial causes for complex problems, it is helpful to separate possible etiologies into individual parts. In exploring the root causes for gender disparities in cardiac care, we must consider patient-related factors, societal pressures/factors as well as physician and healthcare system related factors.

Patient-centric causes

It is clear that women often have different stressors than men. The data supports the idea that women who work feel a profound pressure to excel at all aspects of life: mother, professional and wife. Many women feel that in order to attain success, she must put others’ needs ahead of her own. Even in women who do not work outside the home but are homemakers who care for children and support a spouse in his career, there is often a lack of attention paid to their own needs. Women seek out less care than men and often present much later in the course of their disease. Often, women do not take the time to work on risk factor modification and continue with negative health habits.

In many families it is the mother who makes sure that the children have all of their preventative health appointments and regular physical exams. The mother makes sure that the children have received any medications and tests that they may need. Often, the female spouse is involved in making sure that her male spouse makes and attends his preventative healthcare appointments. Moreover, if lifestyle changes must be made — such as changes in diet and exercise — it is often the wife who makes sure that the husband is able to comply. When women spend so much time advocating for others — children and spouse — their own needs often are forgotten. By the time a busy wife and mother has finished a day’s work, prepared dinner and cared for the family, exercise and time focused on her own health is not a priority.

In many families in the modern era, males have taken on larger roles in caregiving for children as well as in meal preparation and other household duties. Marriage in the US and the UK today is much more of a partnership — this is in stark contrast to the 1950s stereotype. However, women continue to experience more stress at home as compared to men. Given the extreme pressure that women feel to excel and to provide for the needs of the family, it is common to see anxiety and depression in many professional women. The development of depression and anxiety can further complicate her ability to take control of her own healthcare and make healthy lifestyle choices.

It is clear that one specific reason why women may not seek out care may very well be that they are absolutely overwhelmed by multiple roles. Men deal with professional stressors but seem to be able to relax once at home. In contrast, women who work simply continue the stressful work associated with family life upon entering the home in the evening. The bottom line is that women feel that they do not have any time left for themselves. In order to excel at all roles — work, wife and mother — no time is left to focus on their own needs.

Societal pressures

Societal norms place an enormous pressure on women. In the US today, women are expected to be the primary caregiver for the children in the family and provide a pleasant home environment for her husband. Even though more women work outside the home than in past decades (and 40% are the primary breadwinners) pressures still exist. Some families have adapted remarkably well and the male spouse has begun to accept more of the family/childcare responsibilities — however, these are still in the minority. Women make up a significant proportion of the professional workforce, yet much of our society still expects the images of the 1950s household to continue. Television, movies, magazines and the mainstream media all contribute to the stereotype. Because of this ever-present and ubiquitous exposure to these images of “the perfect wife and mother”, women experience societal pressures that men just do not face. These societal pressures are not without significant consequence. When there are issues in the home such as spousal infidelity or behavioral troubles with the children, many working/ career women immediately blame themselves and the fact that they are attempting to manage both career and home life — a difficult (if not sometimes impossible) balance. This constant feeling of inadequacy can lead to depression as well as other health problems such as hypertension, obesity and type 2 diabetes.

The job of wife and mother leaves very little time for exercise, visits to the doctors and preventative care activities. As a result, obesity, high blood pressure and type 2 diabetes are common — many times these go unnoticed and untreated. Poor nutrition and a sedentary lifestyle become the norm.

Physician/provider factors

Physicians and providers often come to a patient encounter with preconceived notions that may introduce bias and affect their ability to make an accurate diagnosis. Unfortunately, when women present with atypical symptoms (as they often do), they may be quickly labeled as suffering from anxiety or depression. Often they are not properly evaluated for CAD at the time of the physician encounter and are quickly dismissed with an anxiolytic or antidepressant. When clinicians are quick to make assumptions about a particular case, a complete history and physical exam is often never properly performed — adding to the chances of a missed diagnosis. In addition, even though there is scientific evidence to the contrary, many physicians continue to think of heart disease as a disease of men. When discussing preventative care with women, both doctor and patient tend to focus more on breast and gynecological cancer screenings and often lose sight of screening for cardiovascular disease and its risk factors.

Women remain undertreated and underserved when it comes to heart disease. Yet, more women than men die of heart disease every single year. In order to successfully reverse this trend and ensure that women begin to get equal (and evidence-based) treatment we must carefully examine possible explanations for the dichotomy. There are no easy answers to this dilemma. As evidenced by the paucity of data on this subject we have yet to fully understand all of the root causes. For now, we must work to close the gender gap in care through a better understanding of the pressures that women face at home and at work. We must spend more time engaging with each patient during an office visit — we may only get one chance to make a difference and change the course of her disease.

1 Leucken, L. J., Suarez, E. C., Kuhn, C. M. et al. (1997). Stress in employed women: impact of marital status and children at home on neurohormone output and home strain. Psychosom Med, Volume 59, 352–359.

2 Light, K. C., Turner, J. R. and Hinderliter, A. L. (1992). Job strain and ambulatory work blood pressure in healthy young men and women. Hypertension, Volume 20, 214–218.

3 Frankenhaeuser, M., Lundberg, U., Frederickson, M. et al. (1989). Stress on and off the job as related to sex and occupational status in white-collar workers. J Organizational Behav, Volume 10, 321–346.

4 Haynes, S. G. and Feinleib, M. (1982). Women, work, and coronary heart disease: Results from the Framingham 10-year follow-up study. In Berman, P. and Ramey, E. (eds), Women: A Developmental Perspective (NIH Publication No. 82:2298). Washington, DC, US Government Printing Office.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree