Chapter 2

Exercise physiology and training principles

In Chapter 1, we learned of the close anatomical and functional relationships between the respiratory and cardiovascular systems; indeed, they are so integrated that we often refer to the ‘cardiorespiratory’ system. This intimacy is essential for the efficient transport of respired gases to and from the metabolizing tissues of the body. Whilst the cardiorespiratory system operates comfortably within its capacity under resting conditions, during exercise the system imposes a limit upon oxygen delivery, and thence exercise tolerance. In order to understand how the respiratory system contributes to exercise limitation, it is necessary to understand a little of the integrated response of the healthy cardiorespiratory system to exercise, as well as how the individual systems respond to training. This chapter will describe the responses of the cardiorespiratory system to exercise, the limitations it imposes upon exercise tolerance, the concept of cardiorespiratory fitness, and the responses of the cardiorespiratory system to different types of training.

CARDIORESPIRATORY RESPONSES TO EXERCISE

Respiratory

The respiratory pump during exercise

During exercise, the rate and depth of breathing are increased in order to deliver a higher ![]() E and oxygen uptake (

E and oxygen uptake (![]() O2); this response is known as the exercise hyperpnoea, and requires the respiratory muscles to contract more forcefully and to shorten more quickly. At rest, expiratory muscles make very little contribution to breathing, but during exercise they contribute to raising VT and expiratory air-flow rate. However, at all intensities of exercise the majority of the work of breathing is undertaken by the inspiratory muscles; expiration is always assisted to some extent by the elastic energy that is stored in the expanded lungs and rib cage from the preceding inhalation. This elastic energy is ‘donated’ by the contraction of the inspiratory muscles as they stretched and expanded the chest during inhalation. Recent studies have estimated that, during maximal exercise, the work of the inspiratory respiratory muscles demands approximately 16% of the available oxygen (Harms & Dempsey, 1999), which puts into perspective how strenuous breathing can be in healthy young people.

O2); this response is known as the exercise hyperpnoea, and requires the respiratory muscles to contract more forcefully and to shorten more quickly. At rest, expiratory muscles make very little contribution to breathing, but during exercise they contribute to raising VT and expiratory air-flow rate. However, at all intensities of exercise the majority of the work of breathing is undertaken by the inspiratory muscles; expiration is always assisted to some extent by the elastic energy that is stored in the expanded lungs and rib cage from the preceding inhalation. This elastic energy is ‘donated’ by the contraction of the inspiratory muscles as they stretched and expanded the chest during inhalation. Recent studies have estimated that, during maximal exercise, the work of the inspiratory respiratory muscles demands approximately 16% of the available oxygen (Harms & Dempsey, 1999), which puts into perspective how strenuous breathing can be in healthy young people.

The strategy that the respiratory controller adopts in order to deliver a given ![]() E depends upon a number of factors, especially in the presence of disease. Chapter 1 described how the respiratory controller most likely regulates ventilation and breathing pattern so as to ‘keep the operating point of the blood at the optimum while using a minimum of energy’ (Priban & Fincham, 1965). Figure 2.1 illustrates how tidal volume changes as exercise intensity increases, placing it within the subdivisions of the lung volumes that are illustrated in Figure 2.1. Initially, during light exercise, VT increases by the person exhaling more deeply, and utilizing the expiratory reserve volume, but this increase is quickly supplemented as a result of the deeper inhalation and utilization of the inspiratory reserve volume.

E depends upon a number of factors, especially in the presence of disease. Chapter 1 described how the respiratory controller most likely regulates ventilation and breathing pattern so as to ‘keep the operating point of the blood at the optimum while using a minimum of energy’ (Priban & Fincham, 1965). Figure 2.1 illustrates how tidal volume changes as exercise intensity increases, placing it within the subdivisions of the lung volumes that are illustrated in Figure 2.1. Initially, during light exercise, VT increases by the person exhaling more deeply, and utilizing the expiratory reserve volume, but this increase is quickly supplemented as a result of the deeper inhalation and utilization of the inspiratory reserve volume.

Figure 2.1 Changes in tidal volume during exercise of increasing intensity. Note how tidal volume increases as exercise intensity increases. This increase in tidal volume results from utilization of both the inspiratory and expiratory reserve volumes. (From Astrand P-O, Rodahl K, Stromme S, 2003. Textbook of work physiology: physiological bases of exercise, 4th edn. Human Kinetics, Champaign, IL, p. 185, with permission.)

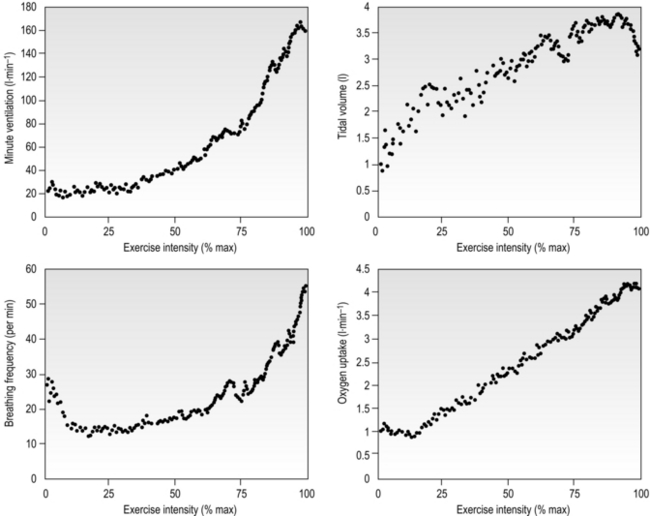

Eventually, VT reaches a point where it does not increase any further, despite a continuing need to increase ![]() E. This can be seen more clearly in Figure 2.2, which shows how

E. This can be seen more clearly in Figure 2.2, which shows how ![]() E, VT, fr and

E, VT, fr and ![]() O2 change during incremental cycling to the limit of tolerance in a well-trained athlete. Each point on the plot represents an individual breath, and there are two key features to note. Firstly, unlike the linear response of

O2 change during incremental cycling to the limit of tolerance in a well-trained athlete. Each point on the plot represents an individual breath, and there are two key features to note. Firstly, unlike the linear response of ![]() O2 to incremental exercise,

O2 to incremental exercise, ![]() E is non-linear, rising steeply at about 70% of maximal intensity. As a result, the

E is non-linear, rising steeply at about 70% of maximal intensity. As a result, the ![]() E required at 80% of maximum capacity is not twice the amount required at 40%; rather, it is more like four or five times greater. Secondly, as VT levels off, fr rises steeply to meet the need for an escalating

E required at 80% of maximum capacity is not twice the amount required at 40%; rather, it is more like four or five times greater. Secondly, as VT levels off, fr rises steeply to meet the need for an escalating ![]() E.

E.

Figure 2.2 Changes in breathing during incremental cycling in a well-trained triathlete. Each dot corresponds to 1 breath. (Adapted from McConnell AK, 2011. Breathe strong, perform better. Human Kinetics, Champaign, IL, with permission.)

The non-linear increase of ![]() E results from the role that breathing plays in compensating for the escalating metabolic acidosis. Chapter 1 described how breathing plays an important role in regulating blood and tissue pH by manipulating the excretion of CO2 at the lungs. At the lactate threshold (LaT), lactic acid (also known as lactate) production exceeds its degradation leading to accumulation of lactic acid in the muscles and blood (see ‘Cardiorespiratory fitness, Lactate threshold’ below). Above the LaT,

E results from the role that breathing plays in compensating for the escalating metabolic acidosis. Chapter 1 described how breathing plays an important role in regulating blood and tissue pH by manipulating the excretion of CO2 at the lungs. At the lactate threshold (LaT), lactic acid (also known as lactate) production exceeds its degradation leading to accumulation of lactic acid in the muscles and blood (see ‘Cardiorespiratory fitness, Lactate threshold’ below). Above the LaT, ![]() E exceeds that required to deliver O2, and the primary role of the respiratory system is stabilizing pH by removal of CO2 via the lungs. This process is known as a ventilatory compensation for a metabolic acidosis (see Ch. 1,‘Acid–base balance’). The steep increase in

E exceeds that required to deliver O2, and the primary role of the respiratory system is stabilizing pH by removal of CO2 via the lungs. This process is known as a ventilatory compensation for a metabolic acidosis (see Ch. 1,‘Acid–base balance’). The steep increase in ![]() E at the LaT is a response to stimulation of the peripheral chemoreceptors by the hydrogen ion component of lactic acid (see Ch. 1, ‘Chemical control of breathing’). This ventilatory response is central to the system that minimizes the acidification of the body and the negative influence of this upon muscle function and fatigue (Box 2.1). As will be described in the section ‘Lactate threshold’ below, the inflection of the response of

E at the LaT is a response to stimulation of the peripheral chemoreceptors by the hydrogen ion component of lactic acid (see Ch. 1, ‘Chemical control of breathing’). This ventilatory response is central to the system that minimizes the acidification of the body and the negative influence of this upon muscle function and fatigue (Box 2.1). As will be described in the section ‘Lactate threshold’ below, the inflection of the response of ![]() E can be used to estimate the exercise intensity at which blood lactate accumulation commences, i.e., the so-called ventilatory threshold. The LaT and ventilatory threshold are related to the same physiological phenomenon, and are often used synonymously. However, they are not identical: the ventilatory threshold lags behind the LaT slightly because it is a response to the elevated hydrogen ion concentration in the blood.

E can be used to estimate the exercise intensity at which blood lactate accumulation commences, i.e., the so-called ventilatory threshold. The LaT and ventilatory threshold are related to the same physiological phenomenon, and are often used synonymously. However, they are not identical: the ventilatory threshold lags behind the LaT slightly because it is a response to the elevated hydrogen ion concentration in the blood.

The increasing reliance upon fr to raise ![]() E at high intensities of exercise arises because it becomes too uncomfortable to continue to increase VT; typically, this occurs when VT is around 60% of FVC. As VT increases, progressively greater inspiratory muscle force is required to overcome the elastance of the respiratory system. Higher inspiratory muscle force output increases effort and breathing discomfort (see Ch. 1, ‘Dyspnoea and breathing effort’). Eventually, the sensory feedback from the inspiratory muscles signals the respiratory centre to change the pattern of breathing, and to increase fr more steeply instead of VT. The respiratory centre has an exquisite system for minimizing breathing discomfort, which also optimizes efficiency. This drive to optimize is also observed in the breathing pattern derangements that are seen in the presence of disease (see Ch. 3).

E at high intensities of exercise arises because it becomes too uncomfortable to continue to increase VT; typically, this occurs when VT is around 60% of FVC. As VT increases, progressively greater inspiratory muscle force is required to overcome the elastance of the respiratory system. Higher inspiratory muscle force output increases effort and breathing discomfort (see Ch. 1, ‘Dyspnoea and breathing effort’). Eventually, the sensory feedback from the inspiratory muscles signals the respiratory centre to change the pattern of breathing, and to increase fr more steeply instead of VT. The respiratory centre has an exquisite system for minimizing breathing discomfort, which also optimizes efficiency. This drive to optimize is also observed in the breathing pattern derangements that are seen in the presence of disease (see Ch. 3).

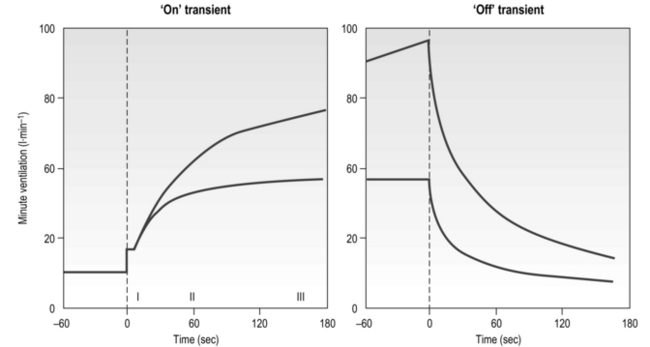

The influence of the LaT upon the exercise hyperpnoea can also be observed during constant intensity exercise. Figure 2.3 illustrates the typical ventilatory responses to two intensities of exercise, one below and one above the LaT. In both intensity domains, the ‘on’ transient response of ![]() E has three phases: phase I is an almost instantaneous increase, which is followed by the monoexponential increase of phase II, and finally phase III, which is either a plateau or a continued, slow increase. During light and moderate-intensity exercise, phase III is a plateau (steady state); in contrast, during heavy exercise phase III continues to show a gradual increase throughout exercise, never achieving a steady state. The absence of a steady state in phase III is due to the presence of a ventilatory compensation for the metabolic acidosis. Unfortunately, this compensation is imperfect, and does not offset the fall in pH completely; accordingly, exercise above the LaT is non-sustainable. At exercise cessation, the ‘off’ transient also displays an abrupt fall in

E has three phases: phase I is an almost instantaneous increase, which is followed by the monoexponential increase of phase II, and finally phase III, which is either a plateau or a continued, slow increase. During light and moderate-intensity exercise, phase III is a plateau (steady state); in contrast, during heavy exercise phase III continues to show a gradual increase throughout exercise, never achieving a steady state. The absence of a steady state in phase III is due to the presence of a ventilatory compensation for the metabolic acidosis. Unfortunately, this compensation is imperfect, and does not offset the fall in pH completely; accordingly, exercise above the LaT is non-sustainable. At exercise cessation, the ‘off’ transient also displays an abrupt fall in ![]() E, followed by exponential decline; the recovery of

E, followed by exponential decline; the recovery of ![]() E following heavy exercise takes much longer than that following light and moderate exercise because of a continued drive to breathe originating from the metabolic acidosis.

E following heavy exercise takes much longer than that following light and moderate exercise because of a continued drive to breathe originating from the metabolic acidosis.

Cardiovascular

A detailed description of the cardiovascular system is beyond the scope of this book, and readers are referred to the numerous excellent textbooks on cardiovascular physiology for a comprehensive description of cardiovascular structure and function (e.g., Levick, 2009). The following section provides an overview of the integrated response of the cardiovascular system to exercise.

The cardiovascular system during exercise

During exercise, both fc and SV increase progressively in order to deliver an appropriate ![]() to the pulmonary and peripheral circulations. As is the case with the increase in respiratory VT during exercise, SV also displays a non-linear response, showing a plateau at around 40–50% of maximal exercise capacity. The reasons for this are complex, but include a number of mechanical limitations that arise from both the filling of the ventricle during diastole and the ability of the heart to eject blood during systole (Gonzalez-Alonso, 2012).

to the pulmonary and peripheral circulations. As is the case with the increase in respiratory VT during exercise, SV also displays a non-linear response, showing a plateau at around 40–50% of maximal exercise capacity. The reasons for this are complex, but include a number of mechanical limitations that arise from both the filling of the ventricle during diastole and the ability of the heart to eject blood during systole (Gonzalez-Alonso, 2012).

Commensurate with this plateau in SV is a plateau in ![]() . As was mentioned above, SV is very amenable to training, and provides the only mechanism by which maximal

. As was mentioned above, SV is very amenable to training, and provides the only mechanism by which maximal ![]() can be increased; this will be described in the section ‘Principles of cardiorespiratory training, Training adaptations’ (below).

can be increased; this will be described in the section ‘Principles of cardiorespiratory training, Training adaptations’ (below).

The control of exercising muscle blood flow is complex, and the factors responsible change as exercise progresses (Hussain & Comtois, 2005). At the immediate onset of exercise, rhythmic contraction of exercising muscles facilitates unidirectional ejection of blood through the venules and deep veins (backflow is prevented by venous valves); during relaxation, venous pressure drops, facilitating the inflow of blood via the arterial circulation. This pumping action also stimulates an increase in muscle blood flow via the release of local vessel endothelial factors that respond to ‘shear stress’ inside the arterioles; in other words, the physical stress exerted on the vessel endothelium by flowing blood stimulates the vessel to relax and dilate. As exercise progresses, muscle metabolism leads to an increase in local metabolites such as CO2, lactic acid, adenosine, potassium ions and osmolarity, as well as a decline in O2. This vasodilator stimulus supplements that from endothelial factors to produce a full-blown exercise hyperaemia (Hussain & Comtois, 2005).

The maximal capacity of the exercising muscles to accommodate blood flow far exceeds the ability of the ![]() to supply it. Accordingly, blood flow to exercising muscles, as well as non-exercising tissues, must be regulated by the sympathetic nervous system, whose job it is to defend arterial blood pressure (ABP). Without this regulatory restraint by the sympathetic nervous system, ABP would fall precipitously. One important component of the mechanism(s) contributing to this restraint is feedback from muscle metaboreceptors (Sinoway & Prophet, 1990). The afferent arm of the resulting reflex response (metaboreflex) is mediated by simple group III and IV afferents residing within skeletal muscles. These afferents sense both mechanical and metabolic stimuli during exercise, and, amongst other things, induce sympathetically mediated, active vasoconstriction in all tissues, including exercising muscles. In tissues with low metabolism this output stimulates powerful vasoconstriction, whist in exercising muscles the resultant vasoconstriction is a balance between the local vasodilatory influence and the neural vasoconstrictor influence.

to supply it. Accordingly, blood flow to exercising muscles, as well as non-exercising tissues, must be regulated by the sympathetic nervous system, whose job it is to defend arterial blood pressure (ABP). Without this regulatory restraint by the sympathetic nervous system, ABP would fall precipitously. One important component of the mechanism(s) contributing to this restraint is feedback from muscle metaboreceptors (Sinoway & Prophet, 1990). The afferent arm of the resulting reflex response (metaboreflex) is mediated by simple group III and IV afferents residing within skeletal muscles. These afferents sense both mechanical and metabolic stimuli during exercise, and, amongst other things, induce sympathetically mediated, active vasoconstriction in all tissues, including exercising muscles. In tissues with low metabolism this output stimulates powerful vasoconstriction, whist in exercising muscles the resultant vasoconstriction is a balance between the local vasodilatory influence and the neural vasoconstrictor influence.

In Chapter 3 (section ‘Respiratory muscle involvement in exercise limitation, Healthy people’) we will consider the ramifications of activation of the metaboreflex originating from exercising respiratory muscles.

MECHANISMS OF FATIGUE

Fatigue is a complex phenomenon that has been studied extensively for over a century. Fatigue and exercise are linked inextricably, and it is impossible to consider exercise without also considering fatigue. But precisely what factors lead human beings to slow down and / or stop exercising, or muscles to cease to generate the force they once could? Despite the extensive literature addressing the phenomenon of fatigue, our understanding remains incomplete. This section is intended to provide a ‘working knowledge’ of fatigue mechanisms for the purposes of understanding the factors that contribute to exercise intolerance in patients, and of specific respiratory muscle fatigue. For a more comprehensive review of fatigue the reader is referred to the excellent overview of skeletal muscle physiology by David Jones and colleagues (Jones et al, 2004), and to the comprehensive guide to muscle fatigue edited by Williams & Ratel (2009).

Definition of fatigue

Even agreeing upon a definition of fatigue has proved elusive – not least because its presence, or otherwise, can be specific to the test, timing and conditions used to detect it. For example, changes in muscle responses to electrical stimulation can differ at different stimulation frequencies such that ‘fatigue’ is revealed only at the ‘right’ frequency. Similarly, any definition of fatigue must recognize that force-generating capacity is not the only muscle property that is affected by the process of fatigue; reductions in muscle power and speed are also indicators of fatigue (see below). Early definitions were oversimplistic, relying upon measurement of isometric force, e.g., ‘the inability to maintain the required or expected force’ (Bigland-Ritchie, 1981). This is not to imply that such definitions are invalid; indeed, this definition is used extensively in the literature as a method to identify respiratory muscle fatigue and to test its relationship to exercise tolerance (Romer & Polkey, 2008). However, this definition is limited and, in 1992, Enoka & Stuart proposed the following definition of fatigue, which encapsulates a number of important characteristics of fatigue that previous definitions had neglected: ‘an acute impairment of performance that includes both an increase in the perceived effort necessary to exert a desired force and an eventual inability to produce this force’ (Enoka & Stuart, 1992). Although Enoka & Stuart’s 1992 definition still focuses upon force as the outcome measure of function, it acknowledges a number of important features of fatigue: (1) the transiency of fatigue, (2) that fatigue can be manifested during movements (not just isometric contractions), (3) that fatigue is associated with sensations, and (4) that fatigue is a process (not an end point). However, although this definition hints at the fact that fatigue can be present before performance declines, and / or task failure occurs, it is not explicit. This important concept is explored in the section ‘Task failure and task dependency’

Indicators of fatigue

For reasons of technical expediency, laboratory studies of fatigue have tended to focus upon measurement of isometric force in the identification of fatigue. These contractions are used to both induce and to measure a decline in function. When asked to maintain a maximal isometric contraction of a limb muscle, with biofeedback of force and encouragement, people can typically sustain the contraction for around a minute. Over the course of the minute, force declines progressively and muscle discomfort rises. Eventually there is an almost complete loss of force, which is followed swiftly by intolerance and cessation of contraction. The difficulty with tests such as this is two-fold: (1) they are not physiological, and (2) it is impossible to distinguish loss of force due to declining effort from loss due to declining function. One way to overcome the second issue is to stimulate the muscle briefly with an electrical stimulus to assess the contractile state of the muscle per se. However, this process is not without its own limitations (see above), and also does not distinguish between decline in effort and decline in the motor drive to the muscle from the spinal cord and brain. Notwithstanding this, electrical stimulation experiments have revealed that fatigue at the level of the contractile machinery is not only associated with a decline in maximal force, it is also associated with slowing of the rate of force development and the rate of relaxation (Cady et al, 1989). Since muscle power is the product of force and speed of contraction, it is obvious that fatigue is associated with a loss of muscle power output.

Potential sites and causes of fatigue

In 1981, Brenda Bigland-Ritchie published a model that identified a number of potential sites / factors influencing fatigue, extending from the motor cortex to the muscle contractile machinery; it also included the influence of the supply the energy for interaction between the contractile proteins (Bigland-Ritchie, 1981). In sequence, these sites / factors were:

1. Excitatory input to the motor cortex

2. Excitatory drive to lower motoneurons

6. Excitation–contraction coupling

Traditional models of fatigue have separated the sites / factors numbered 1 to 6, and classified these as being ‘central’, whilst those numbered 4 to 8 have been classified as being ‘peripheral’. Thus, some locations are involved in both central and peripheral fatigue. Moreover, central fatigue can be located within both the central and peripheral nervous systems, being characterized by a decrease in the neural drive to the muscle. To a large extent, these early classifications of fatigue were made artificially on the basis of the experimental techniques available to study changes in muscle functional properties. In particular, the so-called twitch interpolation technique was used as a method of distinguishing fatigue originating upstream and downstream of the site of electrical stimulation (motor nerve or muscle) (Merton, 1954). The technique was first described by Denny-Brown (1928) and involves the electrical (or latterly, magnetic) stimulation of the muscle of interest, or its motor nerve. The stimulus is delivered during a voluntary contraction of the muscle, and the resulting total force depends upon the extent to which the pool of motor units accessed by the external stimulus has been activated by the voluntary effort. For example, if 100% of motor units accessible to the stimulus are activated by the voluntary drive, no additional force will be evoked by the external stimulation. In contrast, if the voluntary drive has activated only a proportion of this motor unit pool, more motor units will be recruited by the stimulation, and a ‘twitch’ of additional force will be measureable. The latter is indicative of a failure of voluntary neural drive, or ‘central fatigue’. Thus, as Merton (1954) put it, ‘If the equality [between voluntary and electrically evoked forces] still holds, then the site of fatigue must be peripheral to the point [of stimulation] of the nerve; otherwise it is central, wholly or partly’. Using electrical stimulation techniques, it has also been possible to demonstrate that well-motivated people are capable of activating muscles maximally, such that no additional force is generated electrically, compared with voluntary muscle contraction (Merton, 1954), including the respiratory muscles (Similowski et al, 1996).

Early research on fatigue mechanisms tended to focus upon the sites located at the muscle level. This was partly for pragmatic reasons, but also because Merton’s muscle stimulation studies (Merton, 1954) had shown that, during maximal isometric contractions of the adductor pollicis, force could not be restored by strenuous stimulation of the muscles. Because the muscle action potential remained unchanged, the finding indicated the decline in force was due to failure within the muscle and not to failure of neuromuscular transmission. Consequently the neuromuscular junction, the influence of fuel availability and the role of accumulated metabolic ‘waste products’ became a focus of research. At one time, prolonged exercise was understood to be limited by running out of fuel, whereas high-intensity exercise was limited by running out of fuel and / or accumulation of lactic acid (McKenna & Hargreaves, 2008). In other words, fatigue was considered to be a sign of a system in crisis. However, contemporary research on fatigue recognizes not only the important contribution of the brain, but also the fact that fatigue is not a sign of catastrophic failure, but of a system making an integrated response that conserves and optimizes function. For these reasons, and for those explored below in the section ‘Afferent feedback and fatigue’, classification of fatigue as either ‘central’ or ‘peripheral’ has become increasing irrelevant.

Before considering the role of feedback from exercising muscles in fatigue processes, the potential causes of fatigue at the level of the muscle will be discussed briefly (sites 4 to 8; Bigland-Ritchie, 1981). In theory, the neuromuscular junction could present a limit to muscle activation by ‘running out’ of the neurotransmitter acetylcholine. However, there appears to be little evidence to support a role for the neuromuscular junction in fatigue (Bigland-Ritchie et al, 1982). In contrast, a reduction in sarcolemmal excitability is a potential contributor to fatigue. Failure of action potential propagation can arise for a number of reasons. For example, changes in the concentrations of sodium and potassium ions around the muscles fibres can reduce the excitability of those fibres, with a result that force is reduced (Jones et al, 2004). The next step in the process of muscle contraction is excitation–contraction coupling, which involves the release of calcium from the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR). Calcium release, its interaction with troponin, and reuptake into the SR, are fundamental to the contraction and relaxation of muscle fibres. Hence, if release or binding of calcium to troponin is impaired, force can be reduced. Similarly, if reuptake is impaired, relaxation could be slowed. Experiments using single fibres of mouse muscle indicate that repeated bouts of high-intensity exercise can lead to a reduction in calcium release, which is associated with a loss of force (Westerblad et al, 1993

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree