CORONARY ARTERY DISEASE AND CARDIAC CATHETERIZATION

CHAPTER

Evaluation of Chest Discomfort

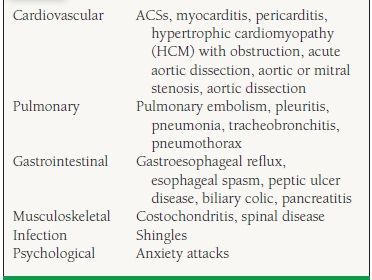

Chest pain or discomfort is a common complaint encountered in virtually every clinical setting: outpatient clinics, emergency departments, hospital floors, and intensive care units (ICUs). The evaluation of chest discomfort is directed by the patient history, chronicity of chest pain, the physical examination, and the clinical scenario. The differential diagnosis (Table 37.1) should remain foremost in the clinician’s mind during the evaluation, with the more life-threatening problems initially excluded and the underlying diagnosis ultimately clarified. What follows is an overview of the evaluation of chest discomfort.

TABLE

37.1 Differential Diagnosis of Chest Pain

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

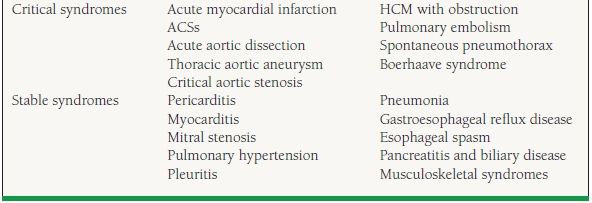

The differential diagnosis for chest discomfort can be divided into those diseases that cause acute chest discomfort and those that cause more subacute or chronic syndromes. Further, the causes of acute chest discomfort can be further subdivided into those syndromes that are urgent, life-threatening problems requiring immediate recognition and treatment, and those that warrant a more measured approach (Table 37.2).

TABLE

37.2 Causes of Acute Chest Discomfort

The acute, life-threatening problems in the differential diagnosis include acute myocardial infarction, acute aortic dissection, pulmonary embolism, spontaneous pneumothorax, and esophageal rupture and acute coronary syndrome (ACS). Hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy with symptomatic obstruction, symptomatic aortic stenosis, and thoracic aortic aneurysm should also be considered in this group. These syndromes are each very different, and their successful recognition and treatment should likewise be individualized (Table 37.2).

Acute pericarditis and myocarditis may cause oppressive symptoms with relatively acute onset. Pulmonary hypertension causing chronic cor pulmonale may be of more insidious onset but can have acute symptoms superimposed. Pneumonia with pleuritis or pleuritis associated with other inflammatory illnesses can cause acute progressive chest discomfort, often exacerbated with inspiration or cough. Gastroesophageal disease such as reflux disease, peptic ulcer disease, and esophageal spasm may cause chest discomfort syndromes that may mimic angina pectoris. A variety of musculoskeletal injuries and inflammatory processes may cause chest wall pain syndromes of acute onset. All of these, while important causes of chest discomfort, are less critical and should therefore be pursued only after the acute, emergent diagnoses have been excluded.

Of the more chronic causes of chest discomfort, chronic stable angina is an important etiology of episodic discomfort. Clinical scenarios that may cause persistent symptoms include chronic cor pulmonale due to chronic venous thromboembolic disease, underlying lung disease, and rheumatologic disease. These syndromes are typically addressed initially in the outpatient setting and may often be worked up on an outpatient basis.

HISTORY

The evaluation should begin with a clinical history focusing on the characteristics of the discomfort. The location, quality, radiation, severity, timing, plaintive and palliative factors, context, and associated symptoms should be carefully and thoroughly documented. These syndrome attributes will form the basis of the physical examination and inform the near-future decisions regarding further diagnostic studies. Further, the patient’s medical, social, and family histories, as well as medication history, are critical to an understanding of the patient’s overall risk for acute and chronic disease processes under consideration.

LOCATION

The location of the discomfort can suggest a specific diagnosis or can help differentiate between chest wall and visceral organ pathology. In the thorax, general visceral afferent pain fibers, including cardiac visceral afferent fibers, course with the corresponding sympathetic fibers back to the spinal cord segments T1—T4. Chest wall and the upper limbs have their origin in the same spinal cord segments. Thus, the central nervous system cannot clearly distinguish pain type and location (i.e., the visceral organs or chest wall). Clinically, we see that the term “chest pain” is often too specific for patients, and they will deny “chest pain” in favor of other, less-specific sensations like pressure or burning. Asking about chest “distress or discomfort” often leads to a story of typical angina pectoris when chest “pains” had been denied. In contrast, focal pains can be localized more consistently when they involve the parietal pleura or the chest wall itself. These structures have cutaneous dermatomal innervation, with inflammation or injury more commonly causing focal pain. Eliciting a careful description of the location of the pain or discomfort is critical to the overall assessment of the syndrome.

QUALITY

The quality of the sensation is, as stated above, important in identifying the involvement of the viscera of the chest, or the chest wall. Is there pain or pressure? Heaviness or burning? These are typical complaints associated with visceral inflammation or injury. However, they are not specific to a particular organ tissue. The “squeezing” of myocardial ischemia may be perceived no differently than the “squeezing” sensation of esophageal spasm or pulmonary hypertension. Likewise, pleuritic pain, a sharp stabbing sensation often exacerbated by breathing or certain positioning, is no different than the perception of pericardial inflammation. Aortic dissection may cause a writhing, tearing, or stabbing sensation that is maximally intense at the onset and inescapable with different positioning, but has no variation with respiration. The quality of the discomfort contributes to the clinician’s overall picture of the syndrome.

RADIATION

Although chest discomfort is often localized to one single spot or generalized area, it may be described as “radiating” or migrating to another location. The discomfort of angina pectoris is often described as radiating to the arms or shoulders, the neck or jaw, or the back. In contrast, the pain of aortic dissection is classically described as tearing through to the back and migrating with the dissection. The pain of pulmonary embolism may cause diffuse, nonspecific tightness or heaviness (likely due to acute right ventricle strain), evolving with time to include a focal pleural component representative of inflammation in the parietal pleura apposed to the infarcted lung tissue. This may felt to be “radiation” of pain or simply a separate component of the syndrome.

SEVERITY

The severity of symptoms can provide the clinician an indication as to the severity of the underlying pathology. Likert pain scales are often used for patient self-assessment of pain severity. Pain scales may be helpful in following the patient’s response to therapy, but in life-threatening clinical scenarios such as acute aortopathies and high-risk ACSs, qualitative improvement on a pain scale should not dissuade the clinician from advancing care. In more chronic syndromes, severity assessment may be helpful in following the progression of the disease.

The physician should make careful note of the symptom complex initial time of onset and the timing of the appearance of new symptoms as they occurred prior to presentation. The duration of symptoms may help differentiate acute ischemic injury or infarction with hours of persistent symptoms from an episode of unstable angina lasting 25 minutes. Furthermore, the duration of symptoms can be an important factor in the decision to administer certain therapies such as pharmacologic thrombolysis in acute myocardial infarction or pulmonary embolism.

PLAINTIVE AND PALLIATIVE FACTORS

An assessment of the modifying factors of the primary complaint may in some cases help inform the diagnosis. Palliation of symptoms with medication such as nitroglycerin or resolution of symptoms with rest, discontinuation of strenuous activity, or changing position (sitting up, resulting in reduced preload and oxygen need) may suggest an anginal picture. Esophageal spasm is also thought to be palliated with nitroglycerin. Conversely, in ACSs, pulmonary embolism, and chronic stable angina, exertion tends to be plaintive. So, while it is important to know what the patient has found to be palliative in his or her discomfort syndrome, it also helps to know what maneuvers may have exacerbated the symptoms.

CONTEXT

The symptom context can assist in differentiating acute musculoskeletal injuries from unstable coronary syndromes. For example, sudden symptoms waking a patient from sleep at 4 am may be more suggestive of an ACS than of a chest wall injury, whereas symptoms occurring while shoveling snow may be less clearly differentiated. Within the context of the occurrence of the symptoms should be an exploration of whether the patient has ever suffered a similar syndrome in the past. If the symptoms are recurrent, any previous studies performed to further evaluate the syndrome may be an invaluable resource. If the symptoms are new, then more aggressive evaluation may be warranted.

ASSOCIATED SYMPTOMS

A thorough exploration of associated symptoms with chest discomfort onset may help guide clinical decision making. Chest discomfort with associated dyspnea, nausea, vomiting, or diaphoresis may suggest significant autonomic and adrenergic activation, consistent with myocardial ischemia. Presyncopal or syncopal symptoms may be more concerning for ischemia-induced arrhythmias or critical aortic stenosis. Again, severity and duration of the symptoms as well as modifying factors may further clarify the picture of the larger syndrome.

MEDICAL HISTORY

An exploration of the patient’s prior medical history must be done and may help identify underlying risk factors for the various disease states under consideration. Risk factors for coronary artery disease, including patient age, presence of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, peripheral vascular disease, history of prior myocardial infarction, cerebrovascular accident, or transient ischemic attacks, all increase the likelihood of the presenting syndrome being attributable to coronary disease or acute aortic pathology. A history of estrogen use, hypercoagulable state, smoking, immobilization, or recent surgery may all point toward venous thromboembolic disease as an underlying cause of presenting symptoms.

SOCIAL, FAMILY, AND MEDICATION HISTORY

Risk factors such as tobacco use, cocaine use, and even herbal supplement use, as in the case of ephedrine, may be helpful in further evaluating an acute chest discomfort syndrome. In addition, an assessment of the patient’s family history may reveal a strong familial history of early coronary events, or aortic pathology as in the case of Marfan syndrome.

Medication history is important in assessing the new patient with chest discomfort. Medical compliance history in addition to the medications themselves and their dosing schedule may contribute to the clinical scenario, for example, a patient with chest discomfort and hypertension who was taking high-dose clonidine but ran out of medication. Rebound phenomena with α– and β-antagonists may be active issues.

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

The physical examination should focus on findings supporting the diagnostic question and assess the suitability of any required invasive procedure. The head and neck examination should include assessment of the carotid pulses for their symmetry and quality of upstroke. The jugular veins should be observed for distention suggestive of volume overload and normal a, c, and v waves. The cardiovascular exam should be sensitive to findings consistent with the differential diagnostic acute chest discomfort possibilities under consideration.

The pulmonary examination should assess for the presence of rales suggestive of fluid overload, but also for symmetric air movement in both lungs, tracheal shift from the midline, dullness to percussion suggestive of pleural effusion, or a cardiac border percussed lateral to the apex suggesting effusion. A complete (carotid, brachial, radial, femoral, popliteal, and dorsalis pedis/posterior tibialis pulsations) survey of the peripheral vasculature should be conducted to assess symmetry of the pulse. Any bruits should be documented, as the presence of bruits in the periphery may help inform the choice of vessel for arterial access if a left heart catheterization is needed. More important, bruits raise the likelihood of coronary insufficiency as the cause of the acute chest discomfort.

The extremities should be examined for edema, evidence of chronic venous stasis, cellulitis, vascular ulcerations, cords, or Homans sign (sign of deep venous thrombosis). Furthermore, an adequate neurologic examination is critical to establish baseline neurologic deficits that may be associated with the chest discomfort syndrome. The use of agents such as sedatives, opiate analgesics, and, more important, thrombolytics may be complicated by alterations in neurologic status.

WORKUP

The pace of the diagnostic evaluation is determined by the clinician’s index of suspicion for critical acute chest disease. Chronic stable syndromes may be evaluated on an outpatient basis with diagnostic studies to rule out symptomatic obstructive coronary artery disease, gastroesophageal disease, peptic ulcer disease, and chronic lung, pericardial, or neuromuscular disease.

In the emergency department, patients presenting with acute chest discomfort are typically evaluated with an electrocardiogram (ECG) and chest x-ray. Critical evaluation of the ECG for evidence of myocardial ischemia, injury, or infarction should be conducted. A chest x-ray should be closely reviewed to assess for the presence of acute parenchymal or mediastinal changes. Serial cardiac markers and observation on telemetry may be performed in clinical observation units in patients at low risk for ACSs. After an appropriate observation period, if the biomarkers and ECG remain negative for evidence of coronary insufficiency, patients may undergo further risk stratification for coronary artery disease through exercise testing prior to discharge. Negative laboratory values and exercise stress testing during close observation is reassuring that the syndrome is unlikely to be attributable to coronary insufficiency, and an evaluation for other, less ominous causes of the chest discomfort syndrome can be pursued on an outpatient basis.

Patients at higher risk for ACS should be treated more aggressively with admission to the hospital and therapeutic anticoagulation, if not contraindicated. If suggested by the history and physical examination, ventilation/perfusion scan or helical computed tomography (CT) to rule out pulmonary embolism should be performed. CT or a transesophageal echocardiogram may be performed to assess for the presence of aortic aneurysm or dissection.

SPECIAL CIRCUMSTANCES

“Atypical chest pain” is a term used to describe a syndrome of discomfort that does not follow the classically described pattern of discomfort attributable to coronary insufficiency. The pretest risk is uncertain based on symptoms, with the clinical risk-factor profile becoming important coupled with the physical examination.

Coronary disease presenting with atypical symptoms occurs more commonly in women and in diabetics. Furthermore, the less common causes of chest discomfort, including the less common causes of myocardial ischemia, are more prevalent in women than in men. The presence of diabetes in women presenting with atypical chest discomfort appears to be the most predictive risk factor for angiographically evident coronary artery disease, arguing that these patients should be treated more aggressively and with a high clinical suspicion for ACS than the less typical symptoms might dictate.

COCAINE-ASSOCIATED CHEST DISCOMFORT

Cocaine use is a commonly encountered comorbidity in patients presenting to the emergency department with acute chest discomfort. The initial evaluation of these patients proceeds in similar fashion to others presenting with similar complaints, save for the recognition that these patients have a higher risk for ACS and myocardial infarction. These patients are often younger and have fewer risk factors for coronary artery disease than those not using cocaine. They are at higher risk due to the increased incidence of accelerated atherosclerotic disease associated with cocaine use plus the increased incidence of coronary vasospasm. In the absence of ECG evidence of ongoing myocardial injury, cocaine-associated chest discomfort should be treated aggressively with antianginals, antiplatelet and antithrombotic therapy until the discomfort is resolved and myocardial infarction has been excluded. One caveat in the treatment of cocaine-associated chest discomfort is that the use of β-antagonists without α-antagonist activity is contraindicated because of the risk of a profound hypertensive response in the setting of unopposed α-activity.

VARIANT OR “PRINZMETAL” ANGINA

A small subset of patients with apparently ischemic chest discomfort and known angiographically normal coronaries suffer from transient vasospastic coronary obstruction. Patients who use tobacco, cocaine, or have other vasospastic syndromes such as Raynaud phenomenon or vascular headaches are at higher risk for variant angina. Patients present with typical anginal symptoms and ECG changes suggestive of acute injury, occurring at rest or with stress and resolving with nitrates and/or calcium antagonist therapy. Patients with recurrent episodes but without ECG changes often need provocative testing in the catheterization laboratory to confirm the diagnosis. Intracoronary ergonovine can reproduce the spasm and symptoms experienced by these patients. These patients frequently respond to therapy with long-acting nitrates and calcium antagonists, though higher than usual doses are often needed.

SUMMARY

The evaluation of chest discomfort syndromes requires the performance of a careful history and physical examination with a focus on risk factors, signs, and symptoms indicative of critical pathology. Some basic laboratory studies and testing may guide the physician toward the diagnosis or help to rule out acute life-threatening syndromes. The pace of the evaluation is determined by the acuity of the clinical scenario and the clinical venue. In the absence of an acute syndrome, risk stratification for the presence of coronary artery disease is commonly undertaken, and further evaluation ensues.

SUGGESTED READINGS

Bugiardini R, Bairey Merz CN. Angina with “normal” coronary arteries: a changing philosophy. JAMA. 2005;293:477–484.

Douglas PS, Ginsburg GS. The evaluation of chest pain in women. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:1311–1315.

Hollander JE. The management of cocaine-associated myocardial ischemia. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:1267–1272.

Lee TH, Goldman L. Evaluation of the patient with acute chest pain. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1187–1195.

QUESTIONS AND ANSWERS

Questions

1. A 23-year-old peripartum female presents with substernal chest pain. Electrocardiogram (ECG) demonstrates ST elevations in II, III, and aVF. The next appropriate step is:

a. Administer aspirin 325 mg, clopidogrel 600 mg, oxygen, nitrates, and heparin weight-adjusted bolus.

b. Administer aspirin 650 mg, clopidogrel 300 mg, oxygen, nitrates, and heparin weight-adjusted bolus.

c. Administer aspirin 650 mg, clopidogrel 600 mg, oxygen, nitrates, and heparin weight-adjusted bolus.

d. Administer oxygen, beta-blocker, and order gated computed tomography (CT) of the chest.

e. Administer oxygen, beta-blocker, and order non-gated CT of the chest.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree