1. Idiopathic (acute and recurrent pericarditis)

2. Infectious

(i) Viral – Coxsackie A/B, echovirus, CMV,EBV, HSV, HBV, HCV, HIV/AIDS, Influenza, adenovirus, varicella, rubella, mumps, parvovirus, B19, HHV6

(ii) Bacterial – Staphylococci, Streptococci, Coxiella burnetti, Borrelia burgdorferi, Haemophilus influenzae, meningococci, Chlamydia, Mycoplasma, Legionella, Leptospira, Legionella, Listeria, rickettsiae

(iii) Mycobacterial – Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare complex (MAIC)

(iv) Fungal – histoplasmosis, coccidioidosis, aspergillosis, blastomycosis, candidiasis

(v) Parasitic – Chagas disease, African tripanosomiasis, echinococcosis, toxoplasmosis, amebiasis, schistosomiasis

3. Systemic inflammatory and autoimmune diseases

(i) Connective tissue diseases – systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, scleroderma, ankylosing spondylitis, mixed connective tissue disease, dermatomyositis

(ii) Vasculitides – Takayasu arteritis, polyarteritis nodosa, Kawasaki disease, temporal arteritis, Churg-Strauss disease, Wegener granulomatosis

(iii) Rheumatic fever

(iv) Granulomatous disease – sarcoidosis

(v) Autoinflammatory diseases – Familial Mediterranean Fever, inflammatory bowel diseases, TNF receptor-1 associated periodic syndrome (TRAPS)

4. Pericardial diseases secondary to diseases of surrounding organs – pericarditis early after myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, myocarditis, aortic aneurysm, pulmonary embolism, pulmonary hypertension, pneumonia, esophageal disease, paraneoplastic

5. Post cardiac injury syndrome – Dressler syndrome (late post myocardial infarction syndrome), post-pericardiotomy syndrome, post heart transplant, pulmonary embolism

6. Neoplastic

(i) Primary tumors – mesothelioma, angiosarcoma

(ii) Secondary tumors – metastatic or by direct extension e.g., lung cancer, breast cancer, Hodgkin’s lymphoma, mesothelioma, gastric and colon cancer, melanoma and sarcoma

7. Mediastinal radiation therapy

8. Hemopericardium and pericardial trauma

(i) Direct injury – penetrating thoracic injury, procedure related trauma (e.g., pacemaker, ablation, PCI, device placement), esophageal perforation

(ii) Indirect injury – cardiopulmonary resuscitation, blunt trauma (e.g., automobile chest impact)

9. Aortic dissection

10. Renal Disease – uremic and dialysis pericarditis

11. Metabolic/Endocrine – hypothyroidism (myxedema), scurvy, ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome

12. Congenital – pericardial cysts, absence of pericardium

13. Drug induced pericarditis – procainamide, hydralazine, isoniazid, methyldopa, phenytoin, penicillin, doxorubicin, daunorubicin, tetracyclines

14. Miscellaneous – cholesterol pericardium, chylopericardium

Important questions in the history of patients with suspected pericardial diseases should focus on recent febrile illnesses, prior pericarditis episodes, recent procedures involving the chest, myocardial infarction (MI), the medication history (e.g., those associated with drug-induced lupus), tuberculosis exposure, travel history, a history of malignancy, previous radiation exposure, renal function, thyroid disease and the patient’s immune status.

Infectious Pericardial Diseases

Viral Pericarditis

Viruses are the most common infectious agents that cause pericarditis. They may invade the pericardium directly, or may indirectly elicit an immune response. The most common viruses to cause pericarditis are echovirus and coxsackieviruses. Other important viral causes in the adult population include cytomegalovirus (CMV), herpesvirus (HSV), human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), and Ebstein-Barr virus (EBV). CMV pericarditis is more common in immune-compromised individuals including post-transplant and HIV patients [5]. In viral pericarditis, there is commonly an upper respiratory tract infection prodrome preceding evidence of pericarditis. Assessment for rising serum viral titers has a limited role in diagnosis as it does not prove causality and most patients will have recovered before the results of such testing is available. Viral pericarditis is usually self- limiting, but may involve the myocardium (myopericarditis), or may lead to effusive or constrictive physiology.

HIV-Related Pericardial Disease

HIV may act on the pericardium by direct invasion, by related opportunistic pathogens, by an indirect immune response and by associated neoplastic involvement (e.g., Kaposi sarcoma and lymphoma). The most common pericardial presentation in HIV patients is simple pericardial effusion, which is present in 10–20 % of cases and has been linked to shorter survival and lower CD4 counts [1–3]. The effusions are usually small, asymptomatic and non-progressive.

Pericardial effusion in HIV patients can also result from severe hypoalbuminemia due to AIDS related cachexia or capillary leak syndrome. The latter results from elevated cytokines (IL-2 and tumor-necrosis factor) that cause a systemic inflammatory response syndrome. HIV treatments, including nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (e.g., abacavir, lamivudine, zidovudine) and protease inhibitors (e.g., saquinavir, ritonavir) may additionally cause lipodystrophy; manifested by increased pericardial fatty tissue, visualized by echocardiography or MRI.

Bacterial Pericarditis

The most common pyogenic bacterial pathogens to invade the pericardium are staphylococci and streptococcal species [4–6] (Fig. 2.1). Less commonly implicated are Haemophilus influenzae, Salmonella enteritidis, Niesseria meningitidis, Legionella pneumophila, Chlamydia pneumoniae, Coxiella burnetii, Treponema pallidum, Borrelia burgdorferi, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, gram negative bacteria and rarely anaerobes. Bacterial pericarditis typically results in the accumulation of purulent fluid in the pericardial sac ranging from a thin layer to large quantities of frank pus. It is a life-threatening condition that presents as an acute febrile illness commonly complicated by tamponade. Though its prevalence has decreased since the advent of antibiotics, purulent pericarditis may result from local extension of suppurative pneumonia or cardiac ring abscess from endocarditis, following chest surgery or trauma, esophageal perforation, sub-diaphragmatic abscess, or from hematogenous or lymphatic spread from a distant focus. In the developing world, tuberculous pericarditis remains the most common cause of chronic pericardial purulence. Patients with uremia, connective tissue disease and immune deficiency are more prone to this condition.

Fig. 2.1

Purulent pericarditis. The parietal pericardium has been removed to expose the purulent material covering the visceral pericardium (Courtesy of Dr. Stephen Sanders, Boston Children’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA)

The most common organism cultured in bacterial pericarditis is Staphylococcus aureus and its route of spread is typically hematogenous. Streptococcus pneumoniae is the most common organism causing purulence by direct extension from an adjacent pneumonia with empyema. Although suppurative foci complicating endocarditis may infiltrate the pericardial space, sterile pericardial effusion is more common in this situation. Salmonella enteritidis has been reported as a cause of purulent pericarditis in patients with HIV, lupus, malignancy and cirrhosis [7]. Esophageal perforation or mediastinal extension of peritonitis is associated with gram negative bacterial pericarditis, and penetrating trauma to the chest (e.g., knife wound) is often polymicrobial. The diagnosis of bacterial pericarditis is confirmed via pericardiocentesis and identification of the responsible pathogen by microscopy and culture. Effusion characteristics are exudative with high protein and low glucose concentrations. Treatment includes drainage of the purulent effusion and systemic antimicrobial therapy. Pericardiocentesis may serve both diagnostic and therapeutic purposes, but a thick effusion with fibrin stranding may prevent the complete drainage of purulent material [6]. Irrigation of the pericardial space with fibrinolytic agents such as urokinase or streptokinase may aid in drainage [8]. The creation of a window via the subxiphoid approach allows a surgeon to mechanically lyse adhesions and more completely evacuate the effusion. In rare instances, a complete open pericardiectomy is required to disrupt adhesions and loculations to allow complete drainage.

Mycobacterial Pericardial Disease

Tuberculous pericarditis arises in approximately 4 % of patients with pulmonary tuberculosis (TB), and while now uncommon in the developed world, it remains an important cause of constrictive pericarditis in developing countries [9], where it is commonly diagnosed in association with AIDS. Mycobacterium tuberculosis infects the pericardium by direct invasion from adjacent tissues (primarily the lungs and the tracheobronchial tree), by hematogenous spread, or from reactivation from an extra-cardiac source. Pathologically four stages of development of pericardial disease occur: (1) granuloma formation with fibrinous exudation containing high concentrations of tuberculous bacilli; (2) serosanguinous effusion with a low concentration of bacilli, high protein and lymphocytic predominant exudate; (3) caseation of granulomas with early pericardial constriction including fibrosis and thickening; and (4) full pericardial constriction, scarring and calcification [10]. Progression among the stages is variable and generally the acute pericardial phase lasts between 2 to 4 weeks and the constriction component may take several years to develop.

Classically patients with tuberculous pericarditis present with fever, weight loss, night sweats and symptoms of right heart failure in the chronic phase, but at any stage may experience chest discomfort, cough and shortness of breath. Constrictive pericarditis can be dry or effusive and subsequently its presentation may vary from right-sided heart failure to tamponade, respectively.

Suspicion of mycobacterial disease starts by recognizing a history of TB exposure or HIV infection. Screening testing (e.g., tuberculin skin test or interferon gamma) may disclose exposure, but does not prove active disease. The diagnosis of TB pericarditis [11, 12] requires the identification of acid-fast bacilli (AFB) by stain or culture (40–60 % sensitive), a positive polymerase chain reaction for the DNA of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in the pericardial effusion, or demonstration of caseating granulomas in biopsied pericardial tissue (80–90 % sensitivity). The diagnostic yield is highest during the effusive stage. An increased level of adenosine deaminase (ADA) >40 units/l in pericardial effusion is 88 % sensitive and 83 % specific for TB. Imaging studies of the chest with CT or MRI may help detect pulmonary and other organ involvement. The mainstay of treatment is multidrug antituberculous therapy, which should be empirically administered when clinical suspicion is high in endemic areas of TB while awaiting conclusive diagnosis. Corticosteroid therapy for tuberculous pericarditis is controversial [13]. While such therapy may shorten the duration of symptoms, there has been no demonstrated survival benefit or prevention of progression to constriction. Surgical treatment of constrictive pericarditis with pericardiectomy is reserved for patients who exhibit persistent hemodynamic findings of constriction.

Fungal Pericarditis

Fungal pericarditis in the immune-competent patient is seen in endemic areas for Histoplasma capsulatum and Coccidioides immitis. Conversely, in the immunocompromised patient, candidiasis, aspergillosis and blastomyces infections are major fungal pathogens. Other patients predisposed to fungal infections are those who have chronic indwelling catheters, dialysis patients, alcoholics, burn victims and in individuals after prolonged antimicrobial therapy [14]. Diagnosis is made by fungal staining, positive cultures from pericardial effusion or tissue, and by measurement of serum titers of anti-fungal antibodies. Other than uncomplicated localized histoplasmosis, treatment usually requires antifungal antimicrobial therapy [15].

Parasite-Related Pericardial Disease

Protozoans and helminthes may affect the pericardium during their migration in the body, or as a target organ [16]. The most common parasitic infection that involves the heart is Chagas disease (American trypanosomiasis) caused by Trypanosoma cruzi, which is endemic to central and south America. It causes myopericarditis acutely and cardiomyopathy in the chronic phase. Conversely, the African form of trypanosomiasis (“sleeping sickness”) caused by T. gambiense or T. rhodesiense may incite pericarditis even months to years following the initial infection. Toxoplasma gondii may result in acute pericarditis in the immune-compromised and progress to constrictive pericarditis. Other rare parasitic causes of pericarditis include Entamoeba histolytica (amebiasis), Echinococcus granulosus, Trichinella spiralis and Schistosoma species.

Pericardial Involvement in Systemic Inflammatory Diseases

Systemic inflammatory diseases encompass rheumatogic diseases, vasculitides, granulomatous conditions, and autoinflammatory diseases. Although pericardial involvement is not uncommon in these disorders, only rarely do patients present with primary cardiac symptoms. Pericardial conditions that can arise during the course of these systemic diseases include acute and recurrent pericarditis and pericardial effusions. Usual screening tests include antinuclear antibodies (ANA) and rheumatoid factor. The overall prognosis of pericardial involvement in systemic inflammatory diseases is good, and only rarely is there progression to cardiac tamponade or constrictive pericarditis.

Rheumatologic Diseases (Connective Tissue Diseases)

Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

Cardiac involvement in systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) can occur in multiple forms, including premature and accelerated coronary atherosclerosis, venous thromboembolism and cardiac inflammation [17]. Pericardial involvement is common and usually benign. Although pericardial effusion develops in >40 % of patients during the course of disease, symptoms of pericarditis occur only occasionally, usually when the systemic disease involves other serosal surfaces (e.g., pleuritis) [18].

Rheumatoid Arthritis

Clinical acute pericarditis arises in approximately 25 % of patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) [19]. When present, pericarditis usually occurs with active rheumatoid disease and other extra-articular manifestations. Symptoms typically respond to high dose aspirin and other NSAIDs.

Systemic Sclerosis

Systemic sclerosis is characterized by the excess production of collagen, which results in fibrosis of involved organs. Although the most common cardiac manifestations are the development of systemic or pulmonary hypertension, it can also directly affect the myocardium, pericardium and conduction system. Symptomatic pericarditis occurs in up to 20 % of patients with systemic sclerosis, while evidence of pericardial involvement is found in >50 % of patients at autopsy [20]. Late constrictive pericarditis can also occur.

Acute Rheumatic Fever

Although rarely seen in the developed world, acute rheumatic fever remains prevalent in developing countries. Acute pericarditis is commonly seen in the first week of acute rheumatic fever, and is a sign of active rheumatic carditis. It usually manifests with a loud pericardial rub, and although pericardial effusion is commonly seen, pericardial tamponade is rare.

Other Rheumatologic Conditions

In patients with polymyostitis and dermatomyositis, pericardial involvement is not as common as other connective tissue disorders, occuring in <10 % of patients [21]. Pericarditis is more common (10–30 %) in patients with mixed connective tissue disorder, but complications such as pericardial tamponade are unusual [21].

Vasculitides

Vasculitides are characterized by inflammation and damage of vessel walls. Large vessel vasculitides include Takayasu arteritis and giant cell arteritis, while medium vessel vasculitis includes polyarteritis nodosa and Kawasaki disease. Small vessel vasculitides includes Churg-Strauss syndrome and Wegener’s disease. Pericardial involvement is rare in the large vessel disorders compared to those with medium and small vasculitides [21].

Granulomatous Diseases

Sarcoidosis is the predominant granulomatous disease with clinically significant pericardial involvement. Although mild to moderate pericardial effusions are commonly detected, symptomatic pericarditis is rare [22].

Autoinflammatory Diseases

Familial Mediterranean fever (FMF) is an autosomal recessive disorder that occurs in specific ethnic groups of Mediterranean countries and presents with recurrent attacks of serositis, including pericarditis. TNF receptor-1 associated periodic syndrome (TRAPS) is a rare autosomal dominant disorder that arises from mutations in the gene that codes for a TNF alpha receptor. Protracted fever, eye, muscle, and pericardial inflammation are clinical manifestations [23].

Pericardial Diseases Secondary to Diseases of Surrounding Organs

Pericardial abnormalities may result from conditions that arise in adjacent structures such as the myocardium (e.g., heart failure, myocardial infarction, myocarditis), the great vessels (e.g., aortic dissection), the lungs (pneumonia and pulmonary embolism), the thoracic duct (e.g., chylopericardium) and the esophagus.

Congestive Heart Failure

Both pericardial and pleural effusions are commonly present in congestive heart failure and myocarditis. Pericardial effusions are related to increased right atrial pressure promoting transudation into the pericardial space [24].

Post Myocardial Infarction Pericarditis

Post myocardial infarction (MI) pericarditis exists in two forms. The first form presents in the first few days after a transmural infarction as a direct extension of inflammation to the pericardium [11, 25]. The incidence of post-infarction pericarditis has decreased to <5 % since the introduction of reperfusion therapies and limitation of infarct size. The classic ECG changes of pericarditis are usually not apparent and the diagnosis is based on clinical suspicion, fever, pleuritic chest pain, and the presence of an effusion by echocardiography. Recommended treatment is aspirin, as other nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents and steroids have been associated with delayed infarct healing [26]. The second form of pericarditis after MI occurs later and is known as Dressler syndrome. When present, it arises weeks after the MI and is presumed to have an autoreactive immune mechanism similar to the post-cardiac injury syndrome described later.

Pulmonary Hypertension

Pericardial effusion arises in up to 25 % of patients with group I pulmonary hypertension (i.e., idiopathic or primary). Larger effusions are associated with right heart failure, elevated right atrial pressures, poor hemodynamic status and worse prognosis [27–29]. These effusions are rarely of hemodynamic significance. Treatment should focus on the primary process and not on the pericardial effusion.

Post Cardiac Injury Syndrome (PCIS)

In addition to Dressler syndrome, pericarditis may occur weeks to months after other forms of cardiac injury including patients who have undergone cardiac surgery (postpericardiotomy syndrome), percutaneous cardiac procedures (e.g., percutaneous coronary interventions, pacemaker lead insertion, electrophysiology ablation procedures), or who have sustained chest trauma [25, 30, 31]. It is presumed that these conditions share a common pathway in which cardiac injury (ischemic, traumatic or iatrogenic) exposes myocardial antigens which incites a systemic inflammatory response. PCIS presents with fever, acute pleuritic chest pain, pericardial effusion and pleural infiltrates and effusions, with elevated inflammatory markers. Of note, colchicine was shown to prophylactically reduce the incidence of PCIS after cardiac surgery in the prospective randomized Colchicine for Post-Pericardiotomy Syndrome (COPPS) trial [32].

Pericardial Trauma

Injury to the pericardium can occur from blunt trauma (e.g., steering wheel impact during a motor vehicle accident or cardiopulmonary resuscitation) or penetrating trauma (e.g., stab or bullet wound, or iatrogenic during medical procedures). In such cases blood accumulates rapidly within the pericardial space such that a small volume of effusion can result in tamponade physiology (as little as 100–200 ml) [33]. In direct injuries to the pericardium with hemodynamic compromise, thoracotomy with surgical exploration is required for survival. As with all types of pericardial injury, PCIS may develop later in the course, and constriction may develop following an organized intra-pericardial hematoma.

Iatrogenic injuries to the pericardium have risen in frequency as the number and complexity of percutaneous interventions increase [11, 33]. Trans-septal puncture to access the left heart appears to hold a high risk of wall perforation (1–3 %), especially if not performed under biplane fluoroscopy or intra-cardiac echocardiogram guidance. Other procedures or hardware that may traumatize the pericardium include pacemaker leads (0.3–3.1 %), guidewires for stent or other hardware placement (0.1–3 %), rotablation (0.1–5.4 %), atherectomy (0–2 %), high pressure stenting (<2 %), mitral valvulopasty (1–4 %), pulmonary artery catheters, endomyocardial biopsies (0.3–5 %), atrial fibrillation ablation (1–6 %) and atrial septal occluder (1.8–3 %). Rescue pericardiocentesis in these situations has a very high success rate (95 %) and the mortality rate is low (<1 %).

Aortic Dissection and Hemopericardium

Hemopericardium is a life-threatening complication of ascending aortic dissection (type A) and pre-operative tamponade is a leading cause of mortality in this condition. A presentation of acute aortic regurgitation with pericardial effusion should raise the suspicion of an ascending aortic dissection, the presence of which can be confirmed by CT or transesophageal echocardiography [34]. Prompt surgical repair of the dissection is required. Preoperative pericardiocentesis with control of intravascular volume has been performed successfully in patients who could not otherwise survive awaiting surgical intervention [35].

Neoplastic Pericardial Disease

Pericardial tumors are uncommon, with metastatic involvement occurring more frequently than primary neoplasms. Neoplastic effusions tend to be large and hemorrhagic. In general autopsy studies of cancer patients, malignant involvement of the pericardium is detected in up to 20 % [36] (Fig. 2.2).

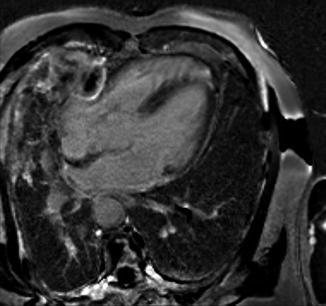

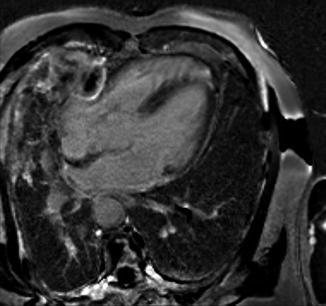

Fig. 2.2

Metastatic disease. MRI delayed enhancement image demonstrating mesothelioma penetrating the pericardium through a pericardial patch (Courtesy of Dr. Michael L. Steigner, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree