Epiphrenic Diverticulum Treatment

Ryan Levy

Catherine Go

Ryan A. Macke

Peter Ferson

James D. Luketich

DEFINITION

Epiphrenic diverticula are those that occur in the distal 10 cm (lower third) of the esophagus. They constitute approximately 20% of all esophageal diverticula. The underlying pathophysiologic mechanism is a result of increased intraluminal pressure, presumably secondary to an esophageal motility disorder. Most commonly, epiphrenic diverticula occur in the setting of achalasia or diffuse esophageal spasm. A high-pressure environment in the esophageal lumen is potentially created by some form of distal functional or mechanical obstruction, such as a nonrelaxing, hypertensive lower esophageal sphincter (LES); repetitive normal to high amplitude simultaneous contractions; or a distal peptic stricture. A prior fundoplication for the treatment of reflux may also lead to epiphrenic diverticula in the setting of an esophageal motility disorder. Any of these processes may lead to herniation of the mucosa and submucosa through an area of weakness in the muscle layers of the esophagus. Epiphrenic diverticula are thus false, or pulsion, diverticula.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

The differential diagnosis of epiphrenic diverticula includes hiatal hernia, esophageal webs and strictures, esophageal duplication cyst, and esophageal carcinoma. Equally relevant is the differential diagnosis of the underlying cause of the epiphrenic diverticulum, which includes achalasia, diffuse esophageal spasm, nonspecific motility disorder, hypertensive LES, end-stage gastroesophageal (GE) reflux disease with a “burnt out” esophagus, peptic stricture, or failed previous fundoplication.

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

Epiphrenic diverticula are estimated to be symptomatic in only 15% to 20% of cases. Typical symptoms include dysphagia and regurgitation. Reflux and chest pain may also commonly occur. Pulmonary symptoms may include chronic cough, productive or purulent sputum, or chronic dyspnea. Malodorous breath may also be present.

On history, it is important to elicit whether the patient experiences symptoms of GE reflux disease, regurgitation, chest pain, or dysphagia. Additional medical history such as recurrent pneumonia, lung abscesses, or repeated aspiration episodes is pertinent. A history of weight loss is not uncommon.

Prior procedures such as esophageal dilations or botulinum toxin injection are also pertinent.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

Epiphrenic diverticula are associated with an underlying esophageal motility disorder in most cases. It is imperative to not only assess the size and location of the diverticulum but also to characterize the motor function of the esophagus.

A barium esophagram is the initial test performed to define the anatomy of the diverticulum and esophagus. Size, location, and right or left sidedness can be determined from the esophagram. This provides a “road map” for operative planning, as diverticula more than 7 to 10 cm above the diaphragm are not easily accessible through the transhiatal route and may be better approached from the chest. Barium esophagrams may also offer information about motility.

High-resolution manometry, the current gold standard, is necessary to evaluate for an underlying esophageal motility disorder. In the setting of achalasia, manometry demonstrates aperistalsis with a nonrelaxing LES. Other manometric patterns seen in the setting of epiphrenic diverticula include diffuse esophageal spasm (80% or more simultaneous contractions of normal amplitude), nonspecific motility disorder, nutcracker esophagus, or hypertensive LES. Failure to identify and treat the underlying motility disorder during diverticulum resection has been associated with high rates of recurrence and leak along the suture line in the range of 10% to 20%.1 Specifically, failure to perform an adequate myotomy in such patients has yielded leak rates exceeding 25% when diverticulectomy alone is performed.

Preoperative upper endoscopy is necessary to examine the esophagus and stomach for the presence of Barrett’s, esophagitis, and to exclude malignancy.2 In addition, the presence of a pop upon passage of the scope across the LES may further confirm the diagnosis of achalasia. Lastly, it is important to remove debris from the diverticulum on the day of surgery.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

The need for surgical resection of epiphrenic diverticula largely depends on the patient’s symptoms. Small, asymptomatic diverticula (less than 3 cm) often do not require intervention. Symptomatic patients with small diverticula may benefit from myotomy (with concomitant partial fundoplication) to correct the underlying motility disorder. Larger diverticula require diverticulectomy in addition to myotomy (with concomitant partial fundoplication).

Preoperative Planning

A review of the barium esophagram is helpful to confirm the size and location of the diverticulum relative to the diaphragm and GE junction. It also defines the esophageal anatomy in terms of degree of esophageal dilation and presence of megaesophagus or sigmoid appearance in the setting of achalasia.

The patient’s diet should be restricted to clear liquids for 2 days prior to surgery to minimize the accumulation of food debris in the diverticulum prior to operation.

The anesthesiologist must be informed that rapid sequence induction is needed to minimize risk of aspiration.

After induction of anesthesia, upper endoscopy should be performed to delineate esophageal anatomy, rule out malignancy, and remove debris from the pouch. Esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) should also evaluate for the presence of a “pop,” which is consistent with achalasia.

Prophylactic antibiotics should be administered prior to skin incision, with consideration given to covering for oral flora, anaerobes, and yeast.

Standard procedures such as sequential compression devices and Foley catheter are employed.

Positioning

Positioning of the patient varies with surgical approach. When approaching epiphrenic diverticula from the abdomen, the patient is positioned supine. If a thoracic approach is chosen, the patient is placed in either a right or left lateral decubitus position. The authors prefer a rightsided video-assisted thoracic surgery (VATS) approach, and therefore use the left lateral decubitus position. If a thoracic approach is used, single-lung ventilation is needed with use of a double lumen endotracheal tube or bronchial blocker.

VIDEO-ASSISTED THORACIC SURGERY

Either a right or left VATS may be used for a minimally invasive thoracic approach to the diverticulum. The location of the diverticulum typically dictates the side of the approach. Classically, distal diverticula have been approached from the left side, whereas more proximal diverticula are more readily approached from the right. However, in the authors’ experience, a right-sided VATS approach works equally well for the classic, distally located right- or left-sided epiphrenic diverticula.

Video-Assisted Thoracic Surgery Port Placement

We commonly employ a five-port approach to VATS resection of epiphrenic diverticula. The port placements are identical to the ports we employ for minimally invasive esophagectomy. Specifically, the surgeon works from the posterior ports, which include an infrascapular tip 5-mm port and a 10-mm port in the 9th interspace along a line parallel to the infrascapular tip port. The remaining three ports are assistant ports and include a 10-mm camera port in the 9th interspace along the posterior axillary line, a 5-mm port for endoscopic suction in the 7th interspace in the midaxillary to posterior axillary line, and a lung retraction 10-mm port in the 5th interspace in the posterior axillary line. See FIG 1 for ideal placement of ports.3

Entering the Chest and Mobilizing the Esophagus

Upon entering the chest, the inferior pulmonary ligament is divided and the lung is retracted superiorly and anteriorly.

A diaphragm stitch is placed through the central tendon of the diaphragm with a 48-in 0-Surgidac Endo Stitch. It is brought out the right flank at the level of the inferior diaphragm insertion using an endoscopic Endo Close device. Tension is applied to the retraction stitch to retract the diaphragm caudally, exposing the distal esophagus and esophageal hiatus.

Using sharp dissection with a heat source such as an ultrasonic scalpel, the mediastinal pleura overlying the esophagus is opened. As much of the pleura as possible is kept intact so that it may be reapproximated over the repair at the end of the procedure. As such, the pleura is gently dissected away from the esophagus. Opening

of the mediastinal pleura from the diaphragm up to the azygous vein is beneficial, as it will be necessary for the performance of a long myotomy. The azygous vein can be divided as needed with an endoscopic stapler.

Once the pleura has been opened adequately, esophageal mobilization is carried out. If an ipsilateral approach is taken to the diverticulum (right VATS for a right-sided diverticulum), minimal mobilization is needed. However, if the diverticulum protrudes on the contralateral aspect of the esophagus, the esophagus must be mobilized so that it may be rotated to provide adequate exposure for dissection of the diverticulum and its neck.

A Penrose drain may be used to encircle the esophagus and aid in esophageal mobilization.

Both vagus nerves should be identified and preserved whenever possible.

It is necessary to expose the entire diverticulum and its neck. The diverticulum may be grasped with an endoscopic Babcock grasper (Snowden-type endoscopic forceps). Alternatively, a long stitch may be placed in the apex of the diverticulum to aid with retraction during dissection. Subsequently, the diverticulum is circumferentially dissected free from its surrounding attachments. It is not uncommon for there to be significant inflammatory type adhesions from the diverticulum to surrounding structures. It is essential to dissect the surrounding esophageal muscle fibers down to the neck of the diverticulum. This maneuver is critical in order to ensure complete resection of the diverticulum at the time of stapling. A common technical error is failure to expose the true neck of the diverticulum, which subsequently results in improper positioning of the stapling device and therefore leaves a residual diverticulum.

Diverticulectomy

Once the neck of the diverticulum is clearly visualized, either the endoscope or a 48- to 54-Fr bougie should be inserted into the esophagus beyond the GE junction. This prevents narrowing of the esophageal lumen during stapling of the diverticulum. If difficulty is encountered passing the bougie, intraoperative upper endoscopy should be performed and a wire passed distally through the true lumen of the esophagus into the stomach. The bougie may then be passed over the wire to minimize risk of perforation.

With minimal tension on the diverticulum, the stapling device is positioned along the base (neck), parallel to the longitudinal axis of the esophagus (FIG 2).

The diverticulum is then transected with a reticulating endoscopic stapler. The authors prefer to use a vascular load for transection of the mucosa and submucosa that comprises the diverticulum.

Esophagomyotomy

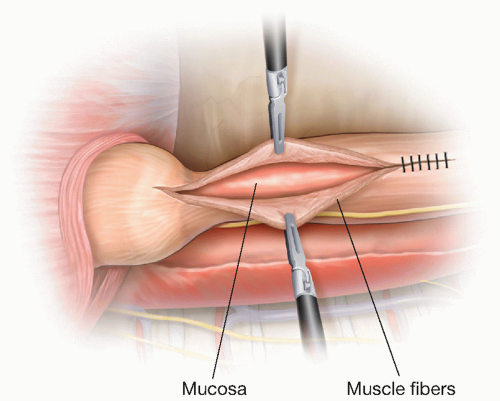

It is preferable to perform the myotomy at least 90 degrees away from the diverticular staple line if possible. The longitudinal esophageal muscle fibers are incised initially with either an ultrasonic scalpel or hook cautery along the direction of the fibers. Alternatively, the myotomy may also be started with a blunt technique by pulling apart the longitudinal muscle fibers. Once the underlying circular muscle fibers are exposed, they are sharply divided. It is critical to lift the circular muscle fibers away from the underlying mucosa to avoid perforation of the mucosa layer (FIG 3).

Attempt to preserve the main vagal trunks while performing the myotomy.

The total length of the myotomy should extend several centimeters (3 to 5 cm) above the proximal extent of the diverticulum. Distally, the myotomy should extend to or across the GE junction, depending on the preoperative manometry results and the underlying pathologic diagnosis. For example, an LES that has a normal resting pressure and normal relaxation may not require myotomy across the GE junction, preserving its natural antireflux function. If the patient has achalasia, the myotomy should ideally extend to 3 cm below the GE junction, carrying the myotomy onto the sling muscle fibers of the gastric cardia.

The muscle layer is dissected laterally off the underlying mucosa for a short distance in the submucosal plane to prevent potential healing of the myotomy site (muscle reconstitution).

The integrity of the myotomy and diverticulectomy sites are submerged under saline and upper endoscopy with insufflation of air is done to check for leaks. Intraoperative mucosal perforations are repaired with interrupted absorbable suture. The muscle layers are then reapproximated over the diverticulectomy staple line with interrupted 2-0 Surgidac Endo Stitch.

The mediastinal pleura may also be loosely reapproximated over the esophagus with interrupted 2-0 Surgidac Endo Stitch for additional protection of the staple line.

The need for an antireflux procedure should also be addressed at this point, depending on the patient’s preoperative reflux symptoms and motility studies.1,4 If the patient carries a diagnosis of achalasia, an antireflux operation should be considered. There are several options at this point. If performing the case from a left VATS, one may attempt a Belsey Mark IV fundoplication. This can be quite challenging and technically demanding from a VATS approach (traditionally performed via left thoracotomy). A second option is to combine VATS with laparoscopy and perform a standard laparoscopic Dor or Toupet (partial) fundoplication. Partial fundoplications are favored in the setting of esophageal motility disorders, as a complete (Nissen) fundoplication may lead to obstruction of the dysmotile esophagus and recurrent diverticula. Lastly, one could forego the antireflux procedure and treat any reflux symptoms with proton pump inhibitors (PPI), opting to perform a fundoplication selectively at a later time depending on patient symptoms and response to medical therapy.

Closure

Once hemostasis is achieved, a pleural drain (chest tube, Blake drain, or pigtail catheter) is placed.

A Jackson-Pratt (JP) drain is also placed along the posterior mediastinum near the diverticula staple line to control any leak that can potentially occur postoperatively.

Intercostal bupivacaine is injected for analgesia.

OPEN THORACIC APPROACH

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree