Epidemiology of Heart Failure

Mikhail Kosiborod

Harlan M. Krumholz

The epidemic of heart failure (HF) is an important public health issue facing the health care system. The scope of the epidemic is profound, with 5 million Americans carrying the diagnosis, 600,000 incident cases, and 1 million hospitalizations occurring annually at a cost of more than $25 billion (1). With no clear evidence that the incidence of HF is decreasing, and with multiple reports of rising prevalence, recent studies project marked increases in the numbers of patients, hospitalizations, and costs associated with HF in the near future (2).

Several key factors need to be considered to better understand the reasons behind the current HF epidemic and its human and economic impact. These include recent trends in HF incidence, prevalence, survival, and hospitalization rates. A detailed review of these factors as well as other pertinent issues, including epidemiology and disease characteristics within special patient populations, will be provided in this chapter.

Incidence

The American Heart Association estimates that there are 600,000 new HF cases diagnosed annually (1), yet analyzing HF incidence is inherently challenging. Most data about HF incidence come from prospective cohort studies, such as the Framingham Heart Study, which consistently apply well-defined criteria for HF diagnosis and account for both inpatient and outpatient cases. However, these studies analyze relatively small, homogeneous patient populations in geographically limited areas and their results are difficult to apply to a diverse population of HF patients in the United States. Although studies of large, administrative databases offer certain advantages, such as analyzing very large patient populations across geographic regions, they rely on hospital billing codes for HF diagnosis and usually do not include outpatients.

Nevertheless, several key investigations offer insight into trends in HF incidence. Most recent studies suggest that the incidence of HF has not changed substantially in the past 30 years. Although data from the Framingham Heart Study showed that the incidence of HF has decreased since the period of 1950-1969, whether any significant change in incidence occurred since 1970 is not as clear (Table 1-1) (3).

In fact, the Rochester Epidemiology Project from Olmsted County, Minnesota, shows that there has been a very modest (and not statistically significant) relative increase in HF incidence of 4% in men and 11% in women between the periods of 1979-1984 and 1996-2000 (4). The same lack of substantial change in incidence is supported by administrative data analysis from the Resource Utilization Among Congestive Heart Failure (REACH) study from the Henry Ford Health System (5).

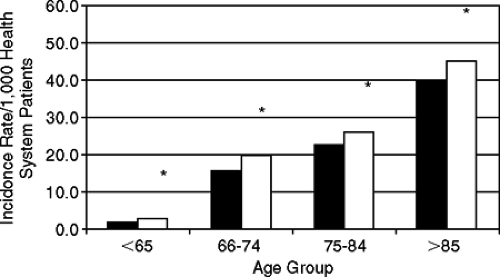

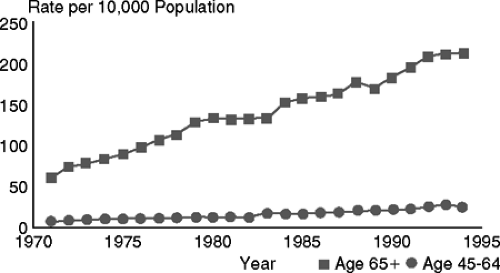

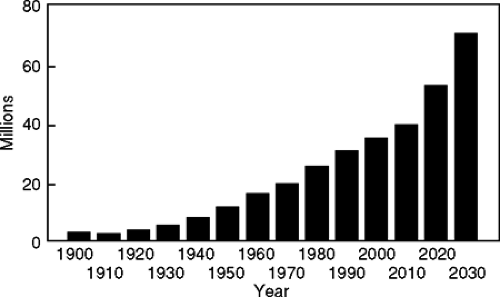

There are several factors that may explain the lack of improvement in HF incidence. First, given the aging of the U.S. population (Fig. 1-1), the number of elderly persons is increasing. There is clear evidence from multiple sources (1,5,6) that HF incidence increases dramatically with age, reaching >40 per 1,000 people in the >85-year age group (Fig. 1-2).

Second, although data indicate that the control of hypertension has improved in recent decades, more than half of patients with a diagnosis of hypertension still have poor control (7,8). Since the prevalence of hypertension is on the rise (8), this could in part be contributing to the unchanged HF incidence rates.

Table 1-1 Temporal Trends in the Age-Adjusted Incidence of Heart Failure | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Third, although mortality after acute myocardial infarction (AMI) is declining (9), the decrease in the incidence of AMI has been less impressive (10). As patients survive longer after AMI, their lifetime risk of HF may be increasing. Finally, the prevalence of diabetes and obesity—both major risk factors for the development of HF—is on the rise (11,12).

Prevalence

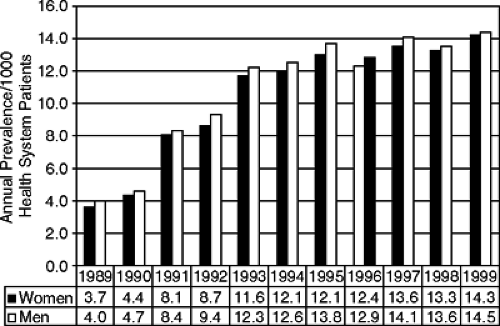

While the incidence of HF has been relatively stable during the past several decades, its prevalence has been rising dramatically and is the main factor underlying the current HF epidemic. It is estimated that the number of people with HF in the United States currently exceeds 5 million, a marked increase from the 1 to 2 million estimated in 1971 (1). This increase in prevalence has also been documented in studies of individual health care systems (5) (Fig. 1-3).

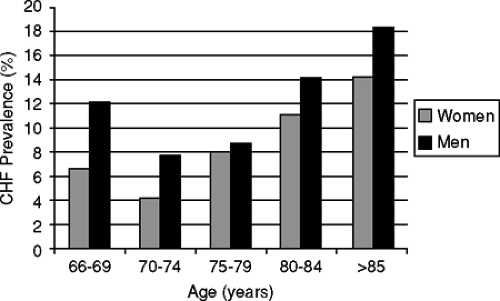

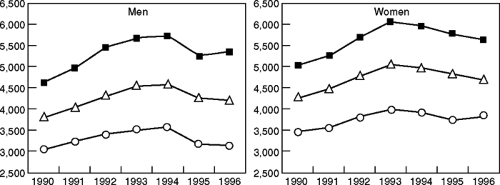

Similar to incidence, the prevalence of HF increases considerably with age. The Rotterdam study (14) demonstrates that while <1% of individuals aged 55 to 64 years are diagnosed with HF, this increases to >17% in the ≥85-year age group. These data are corroborated by findings from the Cardiovascular Health Study (Fig. 1-4) and the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) (6,13,14).

Figure 1-1 Growth of the elderly population (1900 to 2030). (Adapted from U.S. Bureau of the Census.) |

There are several key reasons for the dramatic temporal increases in the prevalence of HF. As mentioned previously, the incidence rates have not declined in recent decades; they remain high. At the same time, recent evidence suggests that although long-term HF mortality remains high, innovations in the management of HF have resulted in slight improvements in survival (3,4,15,16). The rapid increase in the overall number as well as proportion of elderly persons (the group with the highest HF prevalence) in the United States, the lack of decline in incidence, and longer survival with the HF diagnosis are all likely contributors to the rapidly increasing prevalence of HF.

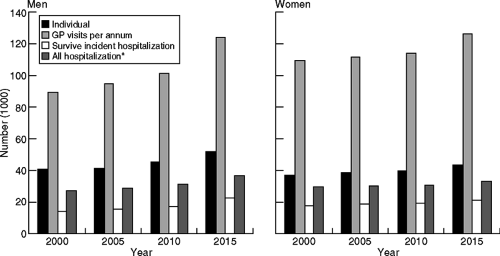

Substantial increases in prevalence are expected in the near future. A recent analysis from Scotland predicts that if current trends in HF incidence and mortality continue, there will be a 31% prevalence increase in men and a 17% increase in women by the year 2020 (2). These increases are likely to have a substantial economic impact, with a subsequent rise in hospitalizations and outpatient visits (Fig. 1-5).

Hospitalizations and Economic Burden

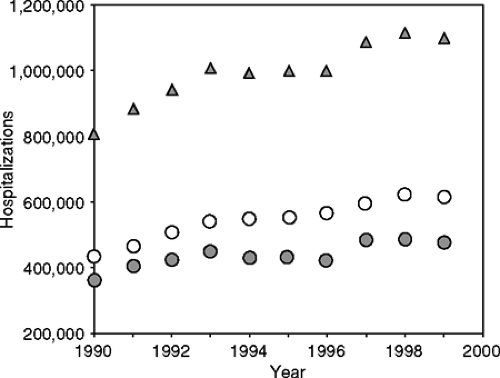

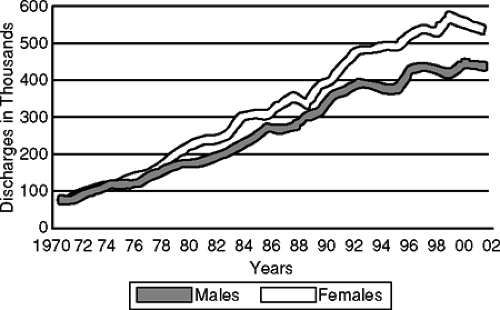

According to data from the National Hospital Discharge Survey, the total number of HF-related hospitalizations has increased from 377,000 in 1979 to 1,088,349 in 1999, a 289% relative increase (1) (Fig. 1-6). It is estimated by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute that hospital charges alone for HF will total nearly $15 billion in 2005 (1).

Although hospitalization rates in both Europe and the United States rose dramatically during the 1980s and early 1990s, more current data on trends in hospitalization rates

have been conflicting. Analysis of national data from Scotland indicates that the total number of hospitalizations with a principal discharge diagnosis of HF peaked in 1993–1994 for both men and women, and has since leveled off (17) (Fig. 1-7). Trends in sex- and age-specific hospitalization rates revealed a similar pattern, with the only exception being men aged ≥85 years, where hospitalization rates continue to increase. Similar administrative database studies from both Sweden and Canada have also shown a relative decrease in HF hospitalization rates between 1993 and 2000 (18,19).

have been conflicting. Analysis of national data from Scotland indicates that the total number of hospitalizations with a principal discharge diagnosis of HF peaked in 1993–1994 for both men and women, and has since leveled off (17) (Fig. 1-7). Trends in sex- and age-specific hospitalization rates revealed a similar pattern, with the only exception being men aged ≥85 years, where hospitalization rates continue to increase. Similar administrative database studies from both Sweden and Canada have also shown a relative decrease in HF hospitalization rates between 1993 and 2000 (18,19).

Figure 1-6 Hospital discharges for congestive heart failure by sex (United States: 1970–2002). (Adapted from American Heart Association Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics—2005 Update. http://www.americanheart.org/presenter.jhtm?identifier=3000090. Accessed June 6, 2005.) |

However, data from the U.S. National Hospital Discharge Survey indicate that the total number of hospitalizations with a primary discharge diagnosis of HF continued to rise during the 1990s; specifically, there has been a 34% relative increase between 1990 and 1999 (20) (Fig. 1-8). A close analysis of the sex-specific hospitalization rates revealed that most of the increase occurred in women, while the rates in men remained relatively stable. National Hospital Discharge Survey data from 1999–2002 are more reassuring, with the total number of hospitalizations decreasing from > 1 million to 970,000, suggesting a plateau similar to that observed in Europe during the mid-1990s (1,21). One possible explanation for this leveling off in HF hospitalizations (despite rising HF prevalence) is that recent innovations in the management of HF, including disease management, may be keeping more patients out of the hospital.

Nevertheless, the long-term outlook for the total number of HF hospitalizations is not as optimistic. Most of the marked increases have taken place in patients aged ≥65 years (Fig. 1-9). Even if age-adjusted hospitalization rates remain stable, given the predicted dramatic aging of the U.S. population, the total number of HF-related hospitalizations will likely rise substantially. Despite the current plateau in HF hospitalizations in Scotland and Canada, considerable future increases in HF hospitalizations and associated costs are predicted in both countries (2,22).

Outcomes

The American Heart Association estimates that more than 50,000 patients die from HF each year. Although data come from a variety of sources, it is clear that despite innovations in the management of this condition, HF outcomes (e.g., mortality and readmissions) remain poor. The estimates for long-term mortality vary significantly, depending on the patient populations studied. Studies that include outpatients as well as inpatients of all age groups, such as the Framingham Heart Study and the Rochester Epidemiology Project, generally produce lower mortality rates than do administrative database investigations, which usually focus on hospitalized elderly patients with HF.

Short-Term Mortality

Most data for in-hospital and 30-day mortality come from administrative database studies in the United States and Canada, with recent estimates ranging between 4% to 5% for in-hospital and 9% to 11% for 30-day mortality (15,16). Although in-hospital mortality markedly declined during the 1990s according to most recent studies (with a 53% relative risk reduction between 1991 and 1997 in one study) (16), the data for 30-day mortality are less clear. In fact, data from Ontario, Canada (15) as well as a recent analysis of national Medicare data (25) both show no change in 30-day mortality from 1992–1999. These data, when considered together with the recent decline in hospital length of stay (23), suggest that although the proportion of patients dying of HF during hospitalization is decreasing, more patients are likely dying out-of-hospital shortly following discharge. Data from northeast Ohio confirm a higher post-discharge mortality in a sample of 23,505 Medicare beneficiaries (16).

Table 1-2 Temporal Trends in Age-Adjusted Mortality After the Onset of Heart Failure Among Men and Women 65 to 74 Years of Age | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Long-Term Mortality

Recent estimates from Framingham report 1- and 5-year age-adjusted mortality after the diagnosis of HF at 28% and 59% for men and 24% and 45% for women, respectively, from 1990–1999 (3) (Table 1-2). The Rochester Epidemiology Project reported slightly lower estimates for 1996–2000 [1- and 5-year age-adjusted mortality of 21% and 50% for men and 17% and 46% for women, respectively (4)], whereas REACH states an overall, crude 1-year case-fatality rate of 15.1% (5). The mortality rates in hospitalized, mostly elderly HF patients are considerably higher: >30% 1-year mortality in the United States, 35% in Canada, and 44% in Scotland (15,24). In fact, the elderly account for nearly 90% of all HF deaths.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree