Chapter One

Epidemiologic Considerations in Cardiovascular Disease

Cardiovascular disease is the number one killer of both men and women in the industrialized world today. Even if we combine all deaths from all types of cancers and HIV-related illness there are more deaths from heart disease. No longer a disease exclusive to men, just over half of all cardiac-related deaths are in women. In the last year, nearly 8.5 million women worldwide died of heart disease and this accounted for one third of all female deaths. Heart disease and heart-disease-related deaths are epidemic: one person dies of heart disease every 33 seconds in the US today.

Obviously, heart disease and its complications remain a major international public health problem. Although great progress has been made over the last 20 years, too many people are dying. Medicine has made great strides in diagnosis, prevention and treatment of cardiovascular disease. However, as healthcare providers, we are not doing enough. Efforts at prevention before disease and risk factor modification after disease presentation are not going far enough — patients are still not being screened and risk factors are not being modified. We must do more to prevent disease and identify those at risk, whether male or female. Awareness and advocacy efforts are lacking and patients are going untreated. In fact, most women consider their greatest risk of death to be from cancers of the breast, ovaries or uterus — in actuality, cardiovascular disease is the number one killer of women worldwide.

According to the Centers for Disease Control (CDC), there are approximately 800,000 deaths annually from cardiovascular disease in the US. Of these, nearly 210,000 deaths are preventable. In the UK and throughout Europe, the percentage of cardiovascular deaths are quite similar. The European Heart Journal reported this year that heart disease is the leading cause of death in Europe and accounts for 46% of all fatalities and affects over 4 million individuals.1 Women represent a significant proportion of cardiac-related death and a substantial number of them are, in fact, preventable. Data from the American Heart Association indicates that 1 in 3 females are living with heart disease today. Since 1984, deaths in women have exceeded those of males.2 Interestingly, during this same time period, only 25–30% of all patients treated with either percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) or coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) were female. Nearly 6.6 million women are living with heart disease in the US today and almost two thirds of those who die suddenly have no prior symptoms of disease. Most women do not even know that they are at risk. In Europe, the numbers of deaths in women attributable to heart disease exceeds those of men — in fact, 51% of females deaths are from cardiovascular disease and only 42% of deaths in men are from cardiovascular disease. As expected, the rates of heart disease and cardiovascular death do vary from country to country in Europe. As a whole, death rates are declining throughout the world but obviously substantial morbidity and mortality still exists.

Recently, a report was released in the US that detailed the fact that preventable deaths from heart disease have declined in older persons but have not declined at nearly the same rate in younger populations (particularly those under the age of 65).3 This is particularly concerning in that it provides clear evidence that we are not doing enough work in prevention in younger patient populations. The fact that preventable deaths are not declining in the younger cohort suggests that physicians and other healthcare providers must do a better job of aggressively screening for and treating of risk factors in patients at earlier ages — even in the 20s and 30s. In this report, rates of preventable cardiovascular deaths declined by 29% in those 75 and younger — however, when the younger population was examined (particularly those in the 40–65 age group) it was found that only 48% of those with high cholesterol were actually treated. Moreover, nearly 29% of these patients were smokers as compared to only 5% in the over-65 category. Older persons tend to have more opportunities for interaction with physicians due to the fact that they often have a larger number of accumulated medical problems requiring regular follow-up care. In contrast, younger adults feel invincible and give almost no thought to prevention or their own mortality. The data is clear — we must change the attitudes of both physicians and patients in order to make an impact in preventable death rates.

In women, these numbers are even more staggering. Although biologically different with a discordant hormonal milieu from men, women present a large number of cases of cardiovascular disease and sudden cardiac death. As previously mentioned, heart disease may present differently in women and may be more difficult to detect and recognize. Women are less likely to seek treatment as compared to men. Women who do seek care are much often treated less aggressively often due to atypical presentations and predetermined attitudes about women presenting with cardiac-like symptoms.

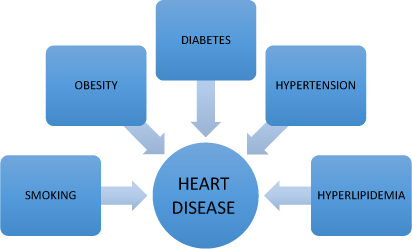

Cardiovascular disease encompasses all of the diseases of the blood vessels heart and lungs. The leading cause of death from cardiovascular disease is coronary artery disease. Coronary artery disease (CAD) is the number one killer of men and women in the US today. Major risk factors for CAD include diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, tobacco abuse and positive family history for CAD. Other risk factors include metabolic syndrome, obesity and sedentary lifestyle. There have been multiple public campaigns in the US and throughout the UK aimed at raising awareness of risk factors and motivating potential patients to effect lifestyle changes.

This year in Circulation, an update on 2013 rates of cardiovascular disease and stroke was published by the American Heart Association (AHA) and the results were quite surprising.2 In spite of efforts to increase awareness, rates of high-risk behaviors continue. With the innovations in diagnosis and treatment available to patients and physicians in the US and in the UK there should be no reason for increasing rates of risk factor prevalence. However, that is not the case.

Smoking

For example, over 20% of men and nearly 17% of women continue to smoke in the US today. According to the British Heart Foundation, 20% of adults continue to smoke. Smoking results in inflammation and damage to the endothelial lining of blood vessels including the coronary arteries and plays a key role in the development of atherosclerotic plaques. On a positive note, the rates of exposure to second-hand smoke of non-smokers has fallen nearly 10% over the same time period — likely due to the passage of smoking bans in public places in many states throughout the US. Other risk factors continue to be ignored as well.

Cholesterol/Hyperlipidemia

According to the CDC the number of adults in the US with cholesterol levels above 240 mg/dL remains at nearly 32 million individuals. In the UK, more than 60% of men and more than 65% of women have high cholesterol. Most are not adequately treated. Chronically elevated serum cholesterol levels leads to deposition in the coronary arteries and development of plaques that may eventually rupture and result in an acute myocardial infarction (AMI). Diet and lifestyle play a critical role in the development of hyperlipidemia and genetic factors predispose patients to higher cholesterol levels requiring drug therapy.

Hypertension

Today, the incidence of hypertension approaches 35%. Of those with hypertension about 75% are aware of their condition but only 50% have their blood pressure under adequate control. Hypertension appears to affect both men and women equally but more men than women are on therapy at any one time. Hypertension results in the loss of compliance of arteries and can result in stiffness and further endothelial damage and inflammation. Untreated or undertreated hypertension can result in damage to other organs including the brain, kidneys, eyes as well as the heart and circulatory system. Those of lower socioeconomic status and those from certain ethnic groups such as Hispanics and African Americans tend to be treated at a lower rate and have a higher incidence of disease. Estimates from the British Heart Foundation indicate that nearly 5 million people are living in the UK with undiagnosed and untreated hypertension — which puts them at significant risk for heart disease.

Diabetes

Diabetes is seen in nearly 9% of the US population (19 million Americans) and another 8 million people have undiagnosed diabetes with almost 30% of people having the syndrome of “pre- diabetes” with high fasting blood glucose levels and evidence of insulin resistance. It is concerning that the incidence of diabetes is increasing significantly in the US today. The largest increase is in type 2 (adult onset diabetes) and appears to be directly related to the epidemic rate of obesity in the US and Europe today. The metabolic affects of long-standing, poorly controlled diabetes significantly contributes to the development of atherosclerotic plaques in the coronary arteries.

Obesity

Obesity in both the US and in the UK continues to pose a major public health problem. Last year, obesity-related illness accounted for nearly 150 billion dollars of healthcare spending in the US alone. Obesity contributes to the development of diabetes, hypertension and high cholesterol. According to the University of Birmingham in the UK, nearly 25% of the British population are considered obese and the numbers continue to rise.4 A Gallup poll conducted in the US in 2013 has shown a steady increase in obesity rates with nearly 27% of Americans now considered obese (as defined by a BMI over 30) and more than 35% are considered overweight.

The rate of rise in obesity appears to be similar in both men and women and across all demographic groups. It appears that we are a culture of over-indulgence and, through poor habits, continue to put ourselves at increased risk for heart disease.

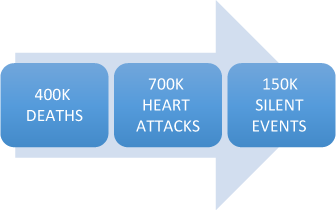

Fortunately, overall death rates in the US from heart disease (across all groups) are declining — however, the burden of disease and the prevalence of risk factors attributable to disease continue to rise. Each year nearly 400,000 Americans die from heart disease and nearly 700,000 Americans experience a heart attack — another 150,000 have a silent, asymptomatic coronary event. One in six deaths in the US today is attributable to CAD — every 34 seconds, one American will have a heart attack and every one minute, a person will die from the event.

Figure 1.1 High-risk behaviors leading to heart disease.

Figure 1.2 Cardiovascular disease in the US claims one in six lives each year.

Clearly, cardiovascular disease is a problem of epidemic proportions and must be addressed in more effective ways. We have the technology and tools to make diagnoses in more efficient ways and we are able to identify risk factors in younger adults. We must cultivate a culture of health rather than a culture of excess. It is clear that unhealthy habits and the development of risk factors for cardiovascular diseases begin early in life. In fact, a study published in The Lancet 5 in November 2013, reported a 25% increase in stroke rates in younger adults — aged 23–64 — that supports the need to intervene early. Stroke rates in patients under the age of 20 have increased significantly over the last ten years. The pathophysiology and risk for both stroke and heart disease are quite similar. This new study should serve as a wake up call for both healthcare professionals as well as young adults to become more engaged in prevention.

The fallout of heart disease

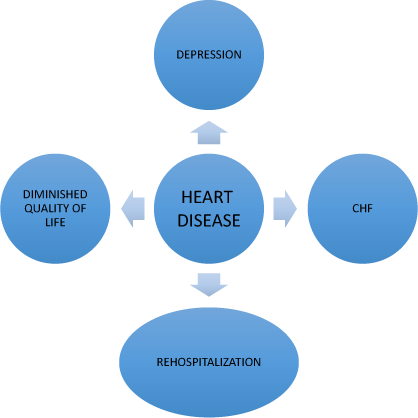

Heart disease can result in significant morbidity. Multiple myocardial infarctions (MI) can result in chronic congestive heart failure (CHF), recurrent hospitalizations and reduced quality of life. Moreover, depression amongst individuals suffering with chronic heart disease is significant and further contributes to exacerbations of heart failure and attacks of unstable angina. Heart disease can limit one’s ability to work and socialize with family and friends. Those that suffer from heart disease are at increased risk for other chronic disease and more susceptible to infection and other severe illnesses. Ultimately, heart disease can result in sudden cardiac death. In many patients who have had a prior MI and have left ventricular dysfunction, the risk of ventricular fibrillation and sudden death is quite high — scar surrounding a prior infarct predisposes these patients to life-threatening arrhythmias. Although the survival rates for sudden cardiac death or cardiac arrest outside of the hospital are quite low, early defibrillation and the advent of implantable cardioverter-defibrillators (ICDs) have improved these rates significantly — but at what ultimate cost? In this era of healthcare reform in the US, we are beginning to look to prevention to help save lives and curtail expenditures. We must continue to develop new strategies that address risk factor modification in hopes of reducing the burden of disease worldwide. The costs to society are great — economically, heart disease and its complications continue to account for a great deal of financial healthcare expenditures both in the US and abroad.

Figure 1.3 Fallout of heart disease.

Women and heart disease — Defining the scope of the problem

According to the American Heart Association nearly 1 in 3 women have some form of cardiovascular disease and, since 1984, deaths in females have greatly exceeded deaths in males. During this same time period, numerous advances in technology to treat heart disease (both acute and chronic) have evolved and resulted in substantial reductions in death. But interestingly in 2010, only 25% of CABG patients and only 32% of PCI patients were female. In 2011, only 32% of transplant patients were female. The dichotomy of equal prevalence and unequal treatment is perplexing and must be better understood in order for change to occur. The fact remains that heart disease in women continues to present a major public health problem — interventions must be made in order to reduce mortality and morbidity in women from cardiovascular disease in both the US and in Europe.

1 Nichols, M., Townsend, N., Scarborough, P. et al. (2013). European Cardiovascular Disease Statistics 4th edition 2012: EuroHeart II, Eur Heart J, Volume 34, 3007–3013.

2 Go, A. S., Mozaffarian, D., Roger, V. L. et al. (2013). Heart disease and stroke statistics — 2013 update: A report from the American Heart Association. Circulation, Volume 127, e6–e245.

3 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2013). Vital signs: avoidable deaths from heart disease, stroke, and hypertensive disease — US, 2001–2010. MMWR, Volume 62(35), 721–727.

4 Reported on the University of Birmingham website. http://www.birmingham.ac.uk/research/activity/mds/centres/obesity/obesity-uk/index.aspx. Accessed 15 April 2014.

5 Felgin, V. L., Forouzanfar, M. H., Krishnamurthi, R . et al. (2014). Global and regional burden of stroke during 1990–2010: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. The Lancet, Volume 383, Issue 9913, 245–255.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree