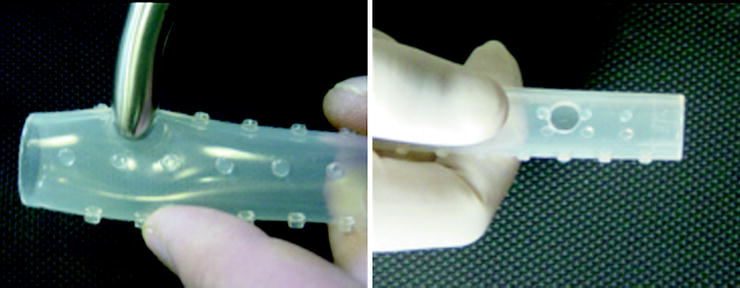

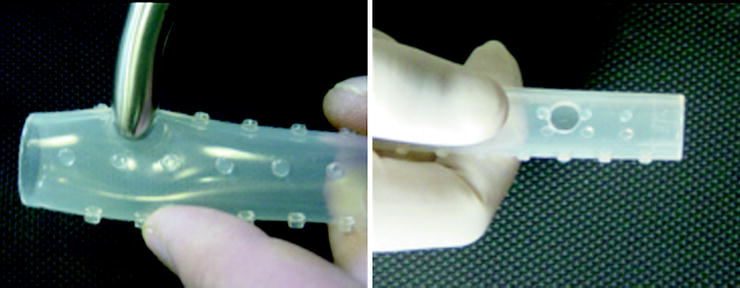

Fig. 29.1

The original Dumon stent (Tracheobronxane ®, Novatech, La Ciotat, France)

Available Silicone Stents

Dumon Stent

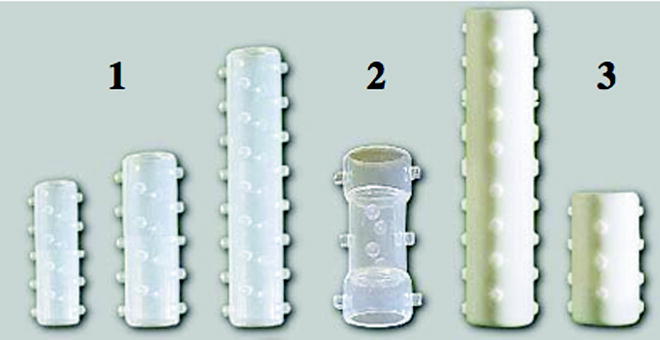

Many silicone stents are commercially available, although the Dumon stent (Tracheobronxane®, Novatech, La Ciotat, France) remains the reference standard as it is the most commonly placed stent worldwide. There are two specific designs: straight and Y (for disease involving the carina, to be treated in another chapter of this book). Stents are available in various lengths and diameters to accommodate both paediatric and adult indications (Fig. 29.2). The largest available external diameter is 20 mm. For irregularly shaped stenoses, i.e. those with marked reduced central airway calibre as compared to the extremities, specialised hourglass-shaped stents are available (Fig. 29.2). These hourglass-shaped stents are particularly useful in cases of short benign tracheal disease. The currently available stents are either made of transparent silicone (non-radio-opaque) or made of silicone melted with barium sulphate (white colour) (radio-opaque) (Fig. 29.2). Soon, the new generation of transparent Dumon silicone stents (Tracheobronxane®, Novatech, La Ciotat, France) will have gold markers included in their studs to provide radio-opacity. The transparent Dumon stent offers the possibility to visualise the mucosa behind its wall.

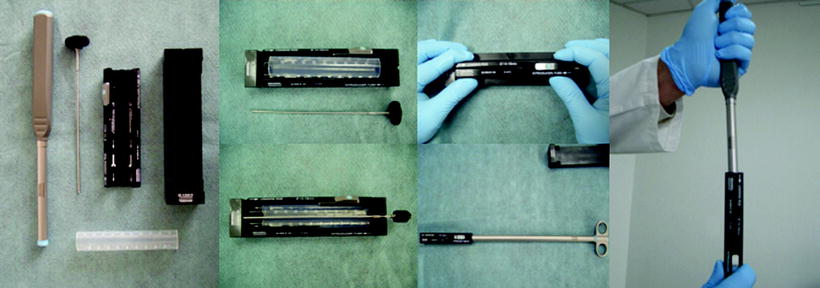

Fig. 29.2

The different designs of Dumon stent: (a) radiotransparent, (b) hourglass shaped and (c) radio-opaque

Dumon stents can be inserted in many different ways. Ideally, it is inserted through a dedicated rigid bronchoscope even if it is feasible using a flexible scope.

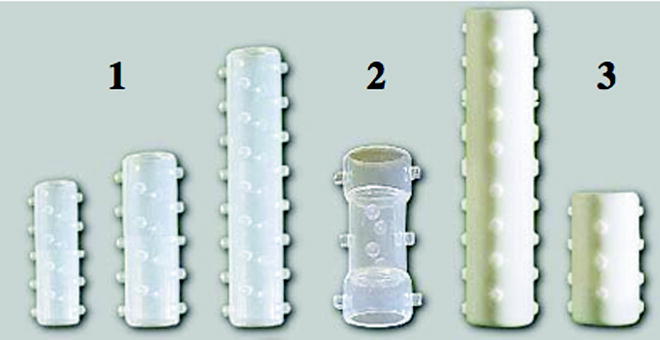

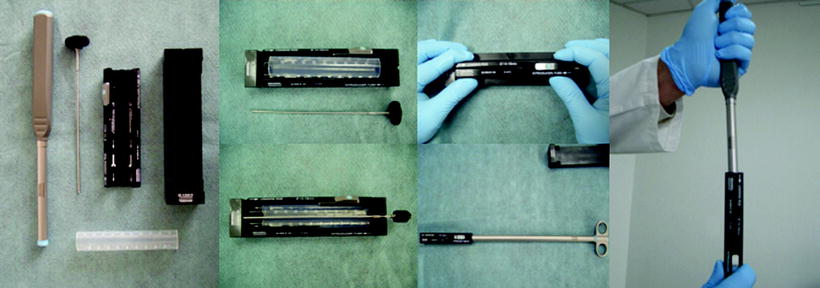

The commercialised introducer set includes a loading tool and a pusher (Fig. 29.3). A Dumon stent can be repositioned, removed and replaced at any time with ease using standard grabbing forceps. On-site modification of these stents is technically possible (Fig. 29.4).

Fig. 29.3

Loading system for Dumon stent (Tonn-Applicator, Novatech, La Ciotat, France)

Fig. 29.4

On-site customization of a Dumon stent (dedicated forceps to create an orifice in order to ventilate a collateral bronchus)

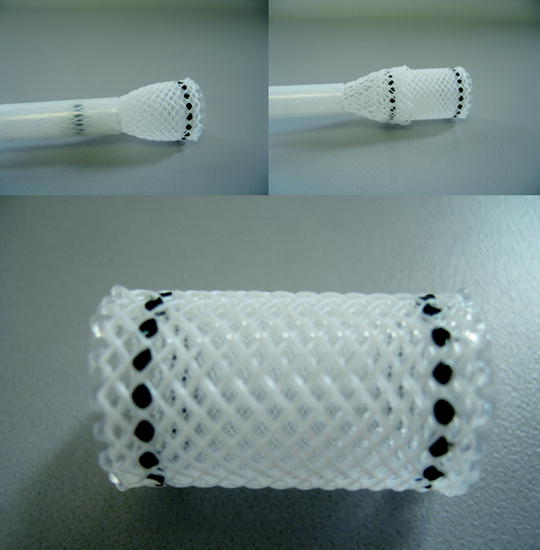

Polyflex Stent

The Polyflex stent (Boston Scientific, Natick, MA, USA) (Fig. 29.5) is made from polyethylene threads embedded in silicone. The walls of these stents are thinner than the walls of Dumon stents resulting in a better ratio of inner to outer diameter. The edges of these stents are sharper and the length of the stent changes depending on its compression state. Due to its design, a Polyflex stent can adapt slightly better to hourglass-type stenoses. The outer surface is slightly smoother, and the migration rate seems to be higher in comparison to the Dumon stent. Modified Polyflex stents with outer struts have been used successfully in recent studies. Little tungsten spots in the stent wall make them visible on chest radiographs. Polyflex stents are deployed out of a semi-rigid tube (Fig. 29.4). The skill and the training that is required to place them are comparable to the competence that is needed to insert Dumon stents.

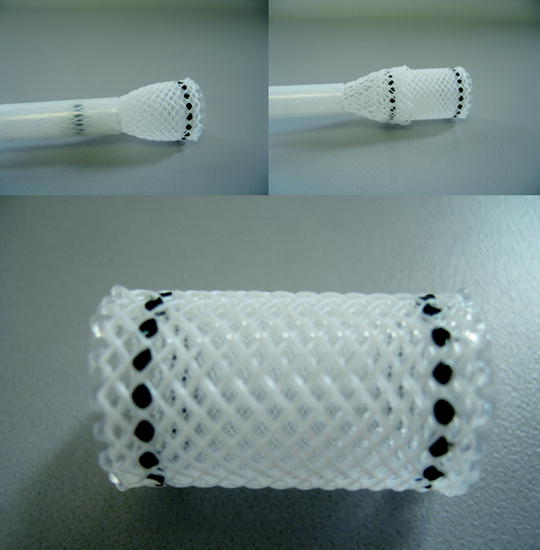

Fig. 29.5

Polyflex stent (Boston Scientific, Natick, MA, USA)

Other Silicone Stents

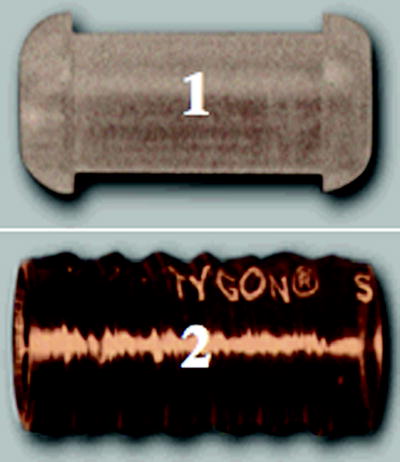

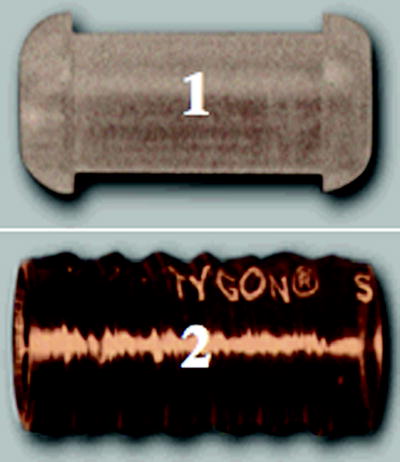

Other CE-marked polymeric straight stents (Fig. 29.6) such as the Noppen stent (Reynders Medical Supply, Lennik, Belgium), which is made from Tygon, or Hood stents (Hood Laboratories, Pembroke, MA, USA), which are made from silicone, may be still available, but they are no longer advertised and have probably been replaced by the newly developed self-expanding metal stents.

Fig. 29.6

Other silicone stents: (1) Hood stent (Hood Laboratories, Pembroke, MA, USA) and (2) Noppen stent (Reynders, Medical Supply, Lennik, Belgium)

As stated above, each stent has specific characteristics differing from those of the Dumon stent and therefore may provide a viable alternative depending on the indication.

Dumon silicone stents (Tracheobronxane®, Novatech, La Ciotat, France) are used nearly exclusively in our institution and are the most widely placed silicone stent, as such the remainder of the article will focus on this type of stent.

Indications

Any pathology leading a significant reduction in airway luminal diameter (greater than 50%) may be an indication for a silicone airway stent.

Five major indications have been established:

Counteracting extrinsic compression from tumours or lymph nodes

Stabilising airway patency after endoscopic removal of intraluminally growing cancer

Treating benign strictures

Stabilising collapsing airways (malacia and polychondritis)

Sealing fistulas, e.g. stump dehiscences or fistulas between the trachea and oesophagus

Malignant Airway Stenosis

The most common indication is malignant airway obstruction from a bronchogenic malignancy. Malignant airway obstruction is often classified based on the airway involvement:

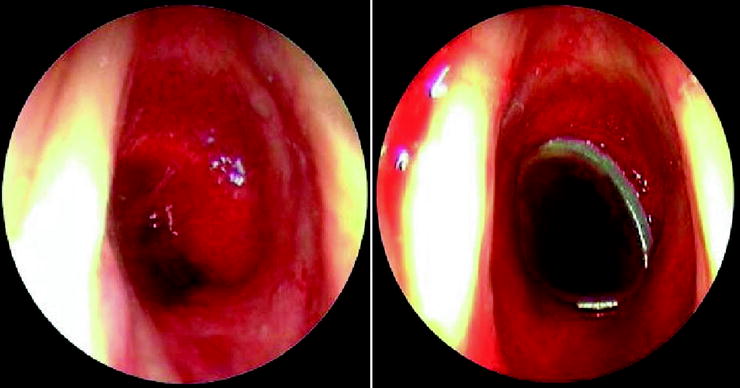

Purely intrinsic involvement can often be managed with debulking techniques to remove the endoluminal tumour (Fig. 29.7). In this case, a stent may be placed as a bridge to the response to chemoradiotherapy, or alternatively it may be considered when there is a high risk of local recurrence.

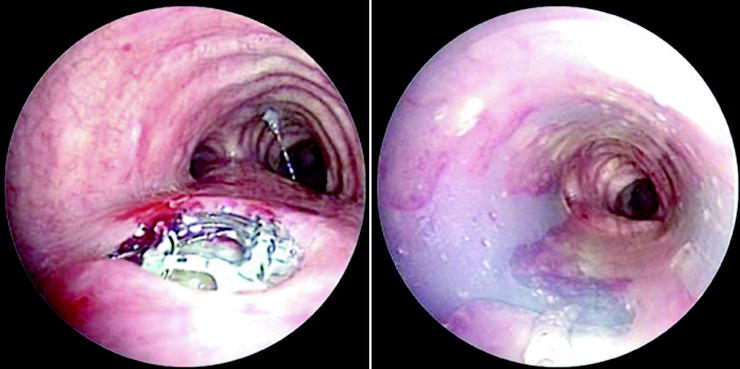

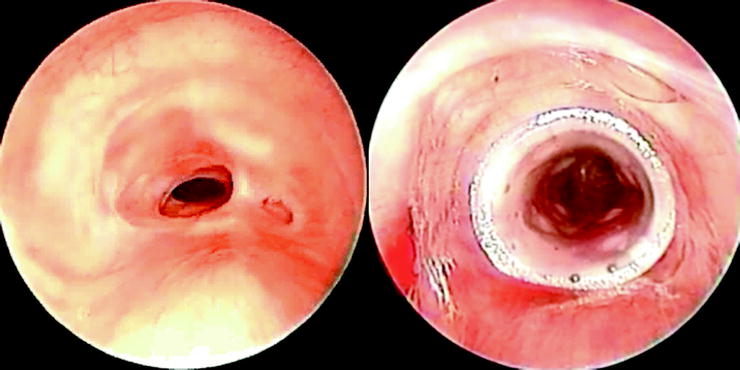

Fig. 29.7

Malignant obstruction of the trachea before and after placement of a silicone stent

The vast majority of cases present with both tumour within the airway, intrinsic, and external compression of the airway, extrinsic. Treatment of mixed disease is usually multimodality with debulking and stent insertion.

Extrinsic compression without intraluminal disease is readily treated with dilatation followed by stenting (Fig. 29.8).

Fig. 29.8

External compression of the trachea before and after silicone stent placement

Other malignant indications for endobronchial stenting include endobronchial metastases from sites (e.g. oesophageal, thyroid, renal cell carcinoma, colon and melanoma) or alternatively low grade tumours (e.g. cylindromas, carcinoids).

Benign Airway Stenosis

Silicone stents are also useful as treatment for benign conditions resulting in central airway obstruction. The most common benign conditions leading to airway obstruction are post-intubation or post-tracheostomy stenosis, post-anastomosis stenoses following sleeve resection, bronchial re-implantation, lung transplantation and tracheobronchomalacia.

Post-intubation or Post-tracheostomy Tracheal Stenoses (PITTS)

PITTS are classified between simple (web-like) and complex (involving the deterioration of the cartilaginous rings) (Fig. 29.9). Simple PITTS are generally not amenable to stent insertion unlike the complex PITTS which recur in about 70% after dilatation alone. Dumon stents are suitable for this indication as they are removable and do not jeopardise a possible postponed surgery unlike metallic stents. This prompted the FDA to published recommendations for the use of metallic stents in this indication.

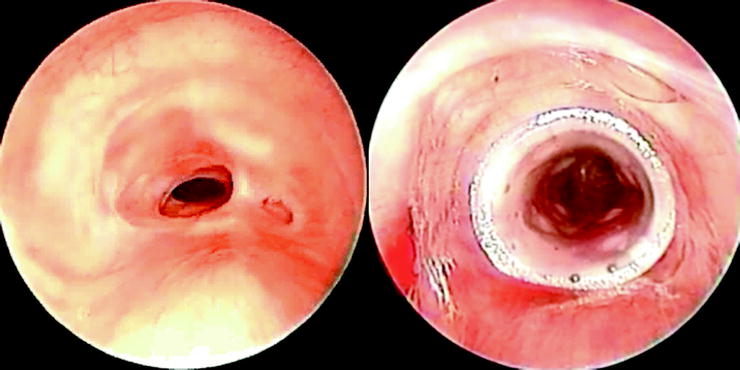

Fig. 29.9

Complex tracheal stenosis before and after silicone stent placement

Migration is probably the most challenging complication in this indication; its rate ranges from 11% to 17.5%, especially when the stenosis is very close to the vocal cords. This can be reduced by the use of a dedicated hourglass silicone stent or by external fixation. Long-term results (no recurrence after stent removal at 1 year) vary from 40% (Brichet) when the stent is placed for 6 months to more than 60% when the stent remains in place for 18 months.

Bronchial Stenosis Following Lung Transplantation

Stent placement could potentially deteriorate mucosal ischaemia, and restenosis is a common finding. While the overall results (survival and clinical outcome) favour stent placement, a high rate of stent-related problems such as scarring, mucus plugging, bacterial colonisation and migration have to be accepted with currently available stents. It is advisable to select a stent that can be removed if necessary without causing further tissue damage. Recently, our group has published a retrospective study on Dumon stent placement in anastomotic stenosis after lung transplantation. The stents have been removed definitely in 70% of the patients without further recurrence.

Tracheobronchomalacia

During recent years, various stents have been used for these indications, but several unanticipated problems have been encountered. Therefore, most endoscopists have become reluctant about the use of permanent stent placement for malacias. The choke region can be identified with new techniques but any procedure may simply shift the choke region towards the periphery and there are no clear predictors whether a patient will benefit from a stabilising procedure. Therefore, in a trial and error approach, it can be considered to temporarily place a stent and test whether the patient improves clinically from this internal splinting. If they do, they are sent to the surgeon for external stenting techniques. If not, the stent is removed and physiotherapy and CPAP is recommended. The straight Dumon stent cannot be recommended for malacic stenoses as it is held in place by contact pressure between the airway wall and the studs. In flexible dyskinetic tracheas and gradually opening benign stenoses, it is prone to migration.

Airway Fistulas

Tracheo-oesophageal or Broncho-oesophageal Fistulas

Tracheo-oesophageal or broncho-oesophageal fistulas are most often secondary to malignancy. Oesophageal carcinomas show airway infiltration in up to 30% of cases. Fewer than half of these patients are resectable. If an oesophago-airway fistula develops, a rapid decline of the overall condition with distressing cough and aspiration pneumonia is usually observed. In rare cases, primary bronchogenic carcinomas invade the oesophagus causing similar problems. Insertion of an oesophageal tube improves the quality of life but usually fails to seal the fistula. Furthermore, the oesophageal tube can protrude into the lumen of the airway and compromise ventilation. Placement of an airway stent can prevent obstruction from the oesophageal tube and can help in sealing the fistula (Fig. 29.10).