End-of-Life Considerations

Marc A. Silver

“Perfection of tools and confusion of goals are characteristics of our time.”

—Albert Einstein

Every other chapter in this text is dedicated to the enhanced diagnosis and treatment of patients who are in the continuum of heart failure stages. This chapter, however, focuses on the situation that occurs when the disease triumphs over the therapies we have to offer and the patient approaches the end of his or her life. Its goal is to help us understand the tools and skills we need, already have, and have yet to acquire to help our patients and their families during the stage of heart failure that leads to death.

Defining End-Stage Heart Failure and Impaired Awareness of Advanced Disease Status

Perhaps the greatest barrier in addressing end-of-life issues for patients with heart failure is the realization of when a patient is at or may be approaching that stage of his or her disease history. The common classification scenarios using clinical signs and symptoms, and even the New York Heart Association functional classification (Class I–IV), have been dysfunctional since clinicians often witness marked status improvements in some patients when therapy is altered. This often leads to an understanding on the part of the patient, the family, and even the treating team of physicians and nurses that the patient is substantially better and has distanced himself or herself from end of life.

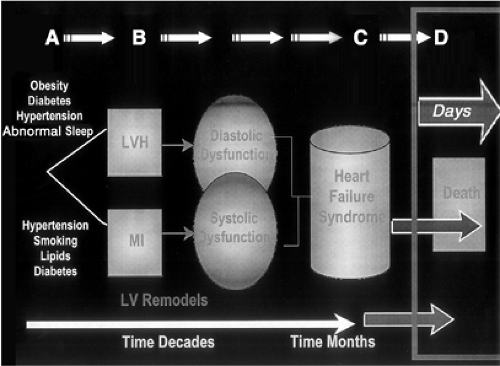

One of the major contributions of the recent American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) guidelines for the management of chronic heart failure was the introduction of a series of stages the patient who was initially at risk and subsequently has heart failure passes through (Stages A–D) (1). Several observations underscore the value of the staging approach. The first is that as a patient progresses from one stage to the next the progress proceeds in one direction only. The patient who develops symptomatic heart failure (e.g., Stage C) has forever missed their opportunity to only be at risk (Stage A) or have only asymptomatic ventricular dysfunction (Stage B). We may be creating a few exceptions to this rule with left ventricular mechanical assist, for example, but in general this observation holds true.

The second key observation regarding this staging system is that while the early stages (Stages A and B) may last years or decades, the latter stages (Stages C and D) are typically measured in years and often only months or weeks (Fig. 48-1). Based on these observations it would seem clear to the physicians and nurses, at least, that the patient who developed the signs and symptoms of heart failure should reasonably be considered a patient in an advanced stage of the disease process. Typically, these patients come to medical attention in greatly decompensated states with multiple organ systems impacted by the heart failure syndrome and its consequences, and yet the gravity often goes unnoticed.

There are myriad other indicators, ranging from neurohormonal measurements to actual Medicare hospitalization mortality rates for patients with heart failure, that indicate the advanced state and proximity to death of these patients (Table 48-1) (2). We are also aware of newer, simple clinical tools that use commonly available clinical and laboratory parameters to define in-hospital mortality as high as 20% for a given heart failure hospital admission

(3). Despite availability of these tools there has been extremely limited attention to or action focused on end-of-life disease planning. The barriers and gaps that can be identified are discussed later; nevertheless, the awareness of the advanced disease status of such patients may be the initial and most important barrier.

(3). Despite availability of these tools there has been extremely limited attention to or action focused on end-of-life disease planning. The barriers and gaps that can be identified are discussed later; nevertheless, the awareness of the advanced disease status of such patients may be the initial and most important barrier.

Even when there is an awareness of advanced disease status for patients, what is often communicated to them and their families is the likelihood of a more prolonged survival than typically occurs. In such cases, all involved may miss the opportunity to prepare adequately for end of life. Heart failure patients are not unique in this disparity in disease status and survival expectation. Even in patients with cancer there is frequently a gap between what is the perceived survival by treating physicians, the communicated survival, and the actual survival (4). Overall, a new paradigm must be developed and continued in the years ahead regarding the role of the professional staff and their need to objectify and identify end-of-life status, to communicate this effectively, as well as to provide better options.

Options for End-of-Life Care for Heart Failure Patients

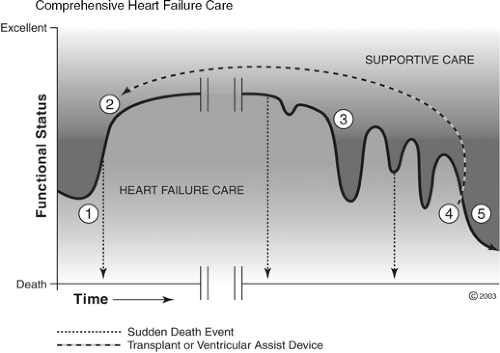

There are many options for patients with advanced heart failure, including those near end of life. As with other stages of heart failure, these options are limited by host factors and timing. For the patient hospitalized with cardiogenic shock and end-organ failure, the options may be quite limited. However, for many patients for whom the advanced state of their heart failure (see previous) and the natural trajectory of the disease state are recognized (Fig. 48-2), the options are more wide-ranging.

The possibilities for patients who are judged to be at the end of life range from simple steps that can be taken to limit further suffering and pain, to broad-scale planning of care, coordination of the care, careful discussions with the patient and those he or she chooses to help him or her in the final stages, and, perhaps equally important, the avoidance of additional tests and procedures. Other measures serve mainly to begin to gain patient and family acceptance and awareness of death. Somewhere in this process the caregiver should have begun to talk about the advanced nature of the disease and the options for advanced heart failure, including transplantation, left ventricular assist, and implanted cardiac defibrillators. Often this begins with a discussion of advanced directives.

Many patients at this advanced stage have already received those advanced therapies. For those who have not, however, a discussion of benefit and life objectives should take place prior to moving ahead with those therapies. The discussion that follows presumes prior discussions regarding advanced therapies and determination that these therapies either have already been employed or are not appropriate for the patient. The caregiver needs also to develop a skill set of communication that extends beyond eliciting advanced directives (5).

Table 48-1 Partial Listing of Metrics for Advanced Heart Failure | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

For the health care provider facing these situations it is best to follow a pattern of discussion so that key information is not presumed by a particular patient or family. In general, these six discussion steps, adopted from Robert Buckman (6), include:

Getting started. This step involves preparation to make sure you have all the medical facts and have the collaboration of other key team members (other consultants, for example). If you are the primary caregiver as viewed by this patient and family, then this responsibility should not be delegated to anyone else or it will lose its import. Also, you should set aside enough time to have the conversation. The conversation should take place in a conducive environment (private, without interruptions) and should include the patient and whomever else he or she may indicate should be there. Once ready to begin, it is most important to introduce the topic and set goals for the conversation, such as, “Mr. Jones, thanks for allowing all of us to speak openly today. Your heart (renal/liver, etc.) failure is getting much worse and I believe you are nearing the end of your life We want to talk today about what you know and would like to know, and have you help us make the right decisions for you, according to your preferences. This will be a difficult conversation but we need to start somewhere. At the end we will talk about options and plans and will proceed according to that plan.”

What does the patient know? This is a key step since, due to fear, illness, significant cognitive dysfunction, and/or depression, there is often a gap between what patients may know about their disease severity and what we might expect them to know. I usually sense that patients are keenly aware of their advanced states but a quick reassessment of their status is always in order. It is useful to review recent hospitalizations, procedures, and steps taken to improve their status and to admit when these did not provide the hoped-for improvement.

How much does the patient want to know? Most caregivers are familiar with the style of interaction they and their patients share, particularly about details regarding their health status. However, it is a good idea to be very clear about which issues are not open for discussion. The patient may make clear that he or she not want to receive certain information (e.g., to not have a discussion about the role of dialysis). The patient may also indicate the desire to pass information on to another family member, thereby not declining the information but, rather, deferring the decisions to someone else. In general, however, most patients will want to hear their current options even if they later defer the decision-making to others. Many other issues impact what patients want to know, including age and culture. We need to assess these special circumstances as they arise.

Sharing the information. This step, in essence, is a succinct clinical summary of the patient’s status, severity of illness, careful assessment of his or her proximity to death, and the background for the discussion that will follow. During this step the provider needs to avoid a long monologue and be alert to understanding—stopping and briefly clarifying questions as they arise.

It is important to maintain eye contact and avoid jargon and euphemisms. Speaking clearly and directly is important to avoid any misinterpretations about the seriousness of the disease state or the conversation. It should be noted that with cancer patients physicians typically overstate their assessment of survival and, indeed, their assessment of survival typically overestimates actual survival. It is acceptable to use brief periods of silence to let the words sink in as well as to check, using visual clues and observing body language, that the message is being assimilated. At the end of this step one can allow for a period of silence; take a brief break and say that you will return in 10 minutes to begin the next discussions. This decision is based on your sense of the patient’s level of understanding. Always ask if there are questions anyone wants clarified before moving on to the next stage. Finally, at the end of this stage you might hear responses that alert you to areas of fear or concern that should be addressed before moving on.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree