Diagnosis

Procedure

In-hospital mortality

Coronary artery disease

Percutaneous coronary intervention

2.1–3.2 % [13]

Coronary artery disease

Coronary artery bypass grafting

4.7–6.0 %

9.2 % mortality for age ≥ 80 years [14]

Heart failure

Aortic Valve Replacement

Transcutaneous

5 % at 30 days

Surgical

8 % at 30 days [17]

Stroke

45.7 % had a poor outcome following discharge

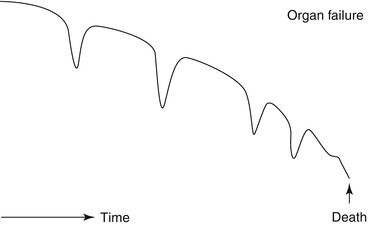

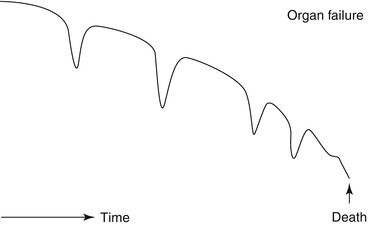

Dyspnea and fatigue are the cardinal manifestations of HF [19] but patients can also present improvement in symptoms, following the model of “organ failure” (Fig. 4.1) [20]. On the other hand, patients with HF have little knowledge of their disease or its treatment [21], and patients and their families frequently do not perceive it as being a serious disease [22]. All these factors can lead to optimism when estimating the risk and assessing life expectancy and may explain why patients in the final stages of HF frequently receive aggressive medical therapies, including intubation, resuscitation, and other measures only a few days before they die. Moreover HF is a disease of the elderly, with a mean age over 75 years and comorbidities may further worsen the prognosis [6, 19–23]. Although HF is known to be a life-shortening condition, equivalent to malignant disease in terms of symptom burden and mortality, it is not always easy to recognize that a patient is entering the final phase of the disease.

Fig. 4.1

Disease progression model in patients with organ failure

Due to the lack of studies referring to specific treatments for HF symptoms in advanced stages there is limited availability of data to guide physicians in the choice of treatments. In these advanced stages, goals like healing and prolonging life can be less important than reducing suffering and improving quality of life [24]. However, only a comparatively small number of HF patients receive specialist palliative care [23, 25, 26], which includes treatment of refractory symptoms as well as facilitates communication and decision making and family support.

Originally related to the care of patients with cancer, palliative care has expanded with the aim to improve the quality of life for patients and their families facing any life-threatening illness [27]. In patients with advanced HF, specific treatment and palliative care should be complementary. There is widespread recognition of the need for integration of palliative care in the care in these patients [19, 28–34]. Improvements in pharmacological, device, and cardiac surgical interventions have led a great number of patients with HF to live for many years following diagnosis, although mortality is still high. Advanced HF programs should involve cardiologists, general practitioners, HF nurses, and palliative care physicians.

Stroke, meanwhile, is one of the most important causes of death worldwide, as well as the leading cause of disability [35, 36]. The impact of stroke is variable and long lasting, and affects both the patient and their caregivers. However, only a few studies have focused on the symptomatic and palliative needs of these patients and their families [37], as most literature refers to acute management, secondary prevention and stroke rehabilitation [38–40]. End-of-life care is very important in acute stroke nursing due to high mortality rates in spite of advances in care [41], and patients with stroke have palliative care needs [42]. Multidisciplinary work should incorporate proper planning and care management as well as good communication with patient and family.

Which Patients Might Benefit from Palliative Care? Patient Selection

Although both health professionals and patients would like to define the prognosis of a subject with HF or acute stroke, the likelihood of survival can be reliably determined only in populations and not in individuals. However, estimating the prognosis of these patients may provide better information to patients and their families to help them to properly plan their future. Patients in stage D HF have a high mortality, with up to 75 % of deaths occurring in the year following the diagnosis and this information can guide decision-making and choice of treatment for these patients. Different analysis and studies performed during the last years have identified some parameters that can be used to assess the expectations of survival in patients with HF [43–45], summarized in Table 4.2. Many of these parameters have been shown to have independent predictive value on mortality in patients with HF and should be taken into account simultaneously, integrating them into predictive models. The CARING (Cancer, Admissions ≥2, Residence in a nursing home, Intensive care unit admit with multiorgan ≥2 Non-cancer hospice Guidelines) criteria have high sensitivity and specificity for death at 1 year [46], although this is a general index, and is not specifically designed for patients with HF. The criteria for approaching death most used are those of the National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization in the United States, which incorporates some specific criteria for patients with HF as well as some general guidelines that include likely death within 6 months, informed consent regarding symptom relief as a therapeutic aim, documentation concerning disease course, and under-nutrition. These criteria are applied as guidelines for Medicare-reimbursed hospice care; however they lack sensitivity or are inadequate when selecting patients, especially among the elderly [47]. Other criteria have also been proposed for admission to palliative care programs and models that have shown to predict mortality in patients with HF [36, 48–52]. However, they were not designed to select patients to palliative care, are complex, and were built from populations with few elderly patients, comorbid patients, women, and nonwhite races [53]. With the exception of the EFFECT tool [52], most of these models do not account for other co-morbidity, frailty or impairment of patient’s functional status that have been proved to be independent prognostic factors [54–56], thus having significant limitations when predicting survival [30] particularly in the elderly [57]. Alternatively, patients who may benefit from a palliative approach may be identified using different criteria, based on easy-to-detect clinical characteristics from the time of admission onward, and thus facilitating the identification of people nearing the end of life regardless of the reasons for admission. The MAGGIC meta-analysis [58] identifies 13 independent predictors of mortality in HF, the most important factors being age, ejection fraction, serum creatinine, New York Heart Association (NYHA class) and diabetes. The score can be easily accessible at the website (www.heartfailurerisk.org). Finally, the patient’s own perception of worsening health status has shown to predict a greater number of hospitalizations, an increase in mortality and greater consumption of resources irrespective of the presence of other poor prognostic factors [59].

Table 4.2

Key prognostic parameters in patients with heart failure

Advanced age |

Left ventricular systolic dysfunction |

Ischemic etiology |

Functional class |

Severe hyponatremia |

Low peak oxygen consumption during exercise |

Low hematocrit |

Wide QRS complex |

Hypotension |

Sinus tachycardia at rest |

Renal insufficiency |

Intolerance to conventional therapy |

Refractory volume overload |

Persistently elevated natriuretic peptides |

Comorbidity |

Frailty |

Regarding cerebrovascular disease, larger strokes with major sequelae and disability, advanced age, previous dementia, previous or acquired depression and some other mental disorders, central post-stroke pain, fatigue, and comorbidities, frailty and worse functional status are the most important factors related to worse prognosis after stroke [37]. Those patients who survive to a stroke often have important physical disability in addition to significant psychological and social limitations [42], and would benefit from addition of palliative care.

Comorbidity, Frailty and Functionality as Prognostic Factors

Comorbidity is the rule in these patients. Its prevalence increases with age, contributing to a poor prognosis. The Charlson comorbidity index is an independent predictor of mortality for patients with HF [60]. Important aspects such as frailty and functional status, not included in most prognostic indexes, also impact the prognosis.

Frailty refers to the reduced ability to overcome physiological stress. Frailty is associated with a HF diagnosis and increased mortality [61]. Although frailty has many components, some criteria have been proposed to facilitate its diagnoses [30], summarized in Table 4.3. Functional status, the group of activities and functions needed to maintain autonomy in everyday physical, mental, and social function, is the single most important factor in predicting hospital mortality in the elderly person [62], surpassing other indexes of disease severity. Other measures of functional state, such as the Barthel basal index, have shown to be predictors of mortality in elderly patients hospitalized for HF [63]. Dependency in the instrumental activities of daily life, cognitive dysfunction, and symptoms of depression are independently associated with mortality in the elderly hospitalized due to medical disease [64]. As heart failure patients may prefer longevity over quality of life [65], it is important to incorporate palliation into heart failure care.

Table 4.3

Criteria proposed for frailty

Weight loss (>10 % weight at 60 years or body mass index <18.5) |

Lack of energy (≤3 on a scale ranging from 0 to 10 or feelings of being abnormally tired or weak during the previous month) |

Limited physical activity (on an activity scale) |

Reduced walking velocity (time spent in walking 4.6 m compared to age-adjusted speed) |

Muscular weakness (as measured by strength test) |

The presence of three or more of these signs or symptoms of frailty has been associated with a worse clinical course, with greater rates of dependency, hospitalization and death |

Cognitive deterioration and depression are often present; 20–30 % of patients with HF [66] and one third of stroke survivors have clinically significant depression [67, 68] which worsens patients’ perception of their state of health, impedes adequate rehabilitation and reduces both quality of life and survival. A recent study demonstrated that 9.1 % patients with an acute ischemic stroke had a history of dementia [69]. Such patients were older and had more severe strokes, and were also less likely to be admitted to a stroke unit or to receive thrombolysis. Those patients with preexisting dementia who did not die during a hospitalization for stroke had higher disability at discharge and were more frequently institutionalized after acute stroke. So, efforts to alleviate symptoms and improve functional status in such population are particularly important. Comorbidity also has an important role in the prognosis and management of patients with acute ischemic stroke [70].

Treatment and Prevention of Sudden Death: Do-Not-Resuscitate Orders

Management of sudden death is discussed in Chap. 7 (Dickinson). Electrical devices (see Lampert Chap. 11) are not appropriate for patients expected to die in the hospital, but symptomatic management of arrhythmias is sometimes appropriate. Amiodarone does not improve survival but as the only antiarrhythmic which has shown not to increase mortality in patients with heart disease [71], it may be an alternative to improve quality of life by reducing the number of arrhythmia episodes. Catheter ablation, an invasive procedure, could also be an alternative to a defibrillator in symptomatic patients to reduce the frequency of arrhythmic episodes [72]. Care for the patient with advanced heart disease and stroke should include a discussion of resuscitation (see Chap. 2– Tanner). Unfortunately, the do-not-resuscitate order, that taken strictly means not implementing cardiopulmonary resuscitation maneuvers, is often associated with a reduction in other treatment and care. After adjusting for the severity of the disease, prognostic factors and age, the patients with these orders are 30 times more likely to die than those without them [73], which may indicate a reduction in the quality of care. Patients and, sometimes, physicians are barely aware that the success rate of resuscitation after cardiopulmonary arrest is low (close to 20 %) [74, 75]. In the Study to Understand Prognosis and Preferences for Treatment (SUPPORT), the prevalence of do-not-resuscitate orders in patients admitted for HF was less than 5 % [75]. In fact, in a ward of patients with HF, physicians frequently have a mistaken view regarding the desire of the patient to receive cardiopulmonary resuscitation or not [51, 76, 77]. We cannot forget the fact that chronic HF patients often have thoughts about death, both during acute exacerbations and chronic stable phases, yet some of them do not feel comfortable considering or talking about their mortality.

The do-not-resuscitate decision should explicitly appear in the medical record of the patient after being agreed with the patient and, if possible, their family, and the medical team. We have previously studied the use of do-not-resuscitate orders and palliative care in 198 consecutive deaths of patients with heart disease that occurred in the cardiology department of our hospital [78]. Interestingly, almost three-fifths of patients who died had a do-not-resuscitate order, although the decision to issue the order was frequently taken after administering aggressive treatment. This decision should be made after thorough assessment of the prognostic and quality of life indexes, and, in case of poor short-term prognosis, aggressive treatments could be avoided.

Regarding patients with acute stroke, families, and patients when possible, ought to be included in ongoing dialogue with physicians, ensuring that the death is both peaceful and dignified [79]. However, information regarding this topic is scarce. Also, it is well known that these patients have a poor prognosis after cardiopulmonary resuscitation maneuvers [80], which should also be considered. In any case, discussions between physicians and patients are especially important at this point [81]. However, there is great variability in the prevalence of do-not-resuscitate orders from one country to other, and even from some centers to others in the same country. A sensitive approach with good communication skills is of great importance in initiating discussion about prognosis of the advanced disease [34, 79].

Increasingly, physicians face patients in the terminal stage of an advanced disease with an implanted cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) device. In HF refractory to treatment or hospitalized with stroke and an ICD, it is appropriate to sensitively inform patients that the ICD treatment of arrhythmias may unnecessarily prolong the dying process and succumbing to a lethal arrhythmia may be a better mode of dying. Patients and their families should be reassured that ICD inactivation is not expected to immediately result in the death of the patient [34]. It is important to follow some steps previous to deactivation of the ICD [82], summarized in Table 4.4. Finally, the decision must be reported in the history (see also Lampert Chap. 11).

Table 4.4

ICD deactivation

A. Steps suggested previous to deactivation of the ICD |

Identification of cause and terminal stage of the situation |

Identification of the risk and benefit of non-deactivation |

Evaluate the capacity and competence of the patient to the decision |

Choose the treatment option most consistent with the overall objective of the patient |

Show respect to any decision of the patient |

B. Optimal timings in which ICD-deactivation should be assessed |

Previous to implantation |

Clinical worsening |

After repeated ICD firing |

When stating do-not-resuscitate orders |

In the final stage of life |

Palliative Care

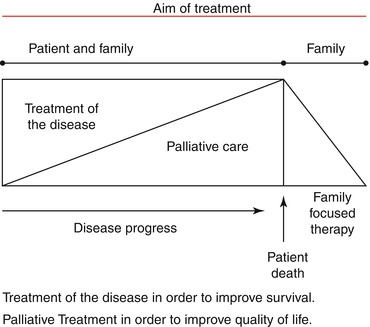

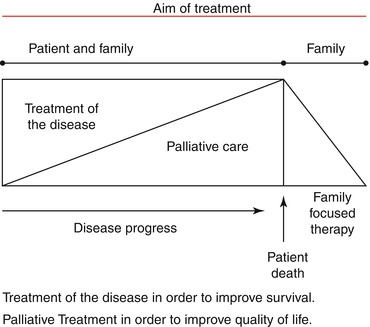

Palliative care refers to those activities aimed at improving the quality of life of the patients and their families facing the problem of a potentially fatal disease, through the prevention and relief of suffering by identification, evaluation and treatment of pain and other physical, psychological, and spiritual problems [27]. This care includes supportive care, focused on alleviating symptoms, complications, and side-effects of interventions. Palliative care is not dependent on a specific health-care team [34], and should not be reserved for patients who are expected to die in a short period (Fig. 4.2), thus, it should be available to all patients needing comprehensive and integrated treatment along the whole disease trajectory, as summarized in Table 4.5. The lack of education among the professionals performing palliative care in HF, and vice versa, is worrying [83], particularly in a advances stages of the disease where “curative” or “life prolonging” therapeutic measures are increasingly ineffective [84, 85].

Fig. 4.2

Aim of treatment related to disease progression. Curative and palliative care can be combined in patients with advanced disease from the beginning

Table 4.5

Palliative care should include the following steps

Optimizing evidence-based therapy |

Sensitively breaking bad news to the patient and family |

Establishing an advanced care plan including documentation of the patients’ preferences for treatment options |

Education and counseling on relevant optimal self-management |

Organizing multidisciplinary services |

Identifying end-stage heart failure |

Re-exploring goals of care |

Optimizing symptom management at the end of life |

Care after death including bereavement support |

Following death, clinicians should acknowledge the grieving process among the family. Poor physician-family communication, being unprepared, failure to satisfy the family, poor symptom control and the lack of involvement of the health personnel during the last stage of life lead to pathological grieving.

As the aim of palliative care is to keep the patient as comfortable as possible, frequently treatment can be reviewed with the aim of simplifying it, since in patients close to death some drugs may be irrelevant. If the oral route of drug administration is not available, alternatives should be utilized, such as intravenous or subcutaneous routes [26]. In patients with advanced HF, death often occurs in hospital, even in those who have been treated at home for long periods [86, 87]. Some patients are concerned that dying at home would put too much stress upon their family, or family members may decline to consider death at home [88, 89]. One study conducted in UK demonstrated that no family member was offered the possibility of the patient dying at home with acute stroke [79]. It may be particularly important to provide caregiver training when patients likely to die with stroke are sent home [90–92].

Palliative Treatment of the Symptoms of Terminal Heart Disease

Scales to evaluate symptoms in patients with advanced HF, like the Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale (MSAS) [93], modified for HF (MSAS-HF) [94], and the Scale of the Edmonton Symptom Assessment (ESAS) [95]. In case of stroke patients, symptoms are often difficult to diagnose and consequently to treat, thus adversely impacting recovery, quality of life and mortality [37]. Patients with impaired communication need special attention [96]. Whatever scale is chosen it should be used to assess the symptoms throughout the course of the disease. A clinical interview should identify those factors that may worsen or improve symptoms, and, in the case of pain, its location and character. Palliative treatment involves diagnosing the cause or causes of each symptom to attempt to treat them. Symptoms need to be effectively evaluated as this is the primary target for treatment in the relief of suffering, but also because symptom characteristics may have prognostic implications in HF patients. Even if the cause of the symptom is irreversible, knowledge of the underlying mechanism should suggest the most appropriate symptomatic treatment [30].

Dyspnea

A total of 60 % of patients who die from advanced HF [97] and over 50 % of stroke survivor [37] suffer from severe dyspnea. Patients with advanced HF are known to have increased ventilation rates for a given volume of expired carbon dioxide thus causing tachypnea and increasing respiratory work, which is independent of symptomatic dyspnea. Pulmonary edema is associated with dyspnea. Together with optimal vasodilator and diuretic treatment, other likely causes should be investigated and treated, such as pleural effusion which can be alleviated by thoracocentesis. When dyspnea persists despite treatment, opioids should be used and these can lead to significant improvement of acute and chronic dyspnea in these patients, as well as ventilatory response [98]. Morphine sulfate or morphine chlorhydrate have the advantage of being able to be administered orally; doses range from 5 to 15 mg/4 h. (See also the detailed discussion in Palliative Care Chap. 3.) Oxygen therapy, even when the patient is not hypoxemic, as well as fresh air directed at the patient’s face can also contribute to the relief of dyspnea. In stroke survivors, dyspnea is also related to older age, female sex and mental condition, and correlates with depression and disability [37], as well as with reduced long-term survival [99, 100]. Except for secondary causes like depression, obstructive sleep apnea, or hematologic, metabolic and endocrine disorders, there is not specific treatment [101].

Pain

Though its cause is not well defined, more than three out of four patients describe pain as the worst of their symptoms in the final phases of HF [102], and pain is severe 3 days before death in 41 % of patients. This pain may be due to cardiac causes, comorbidity (arthrosis, diabetic, or herpetic neuropathy, etc.) or to the medical treatment itself. Chest pain is common, also in the lower limbs and joints. Regardless of the cause, pain should be assessed and treated. Analgesics are the first line: paracetamol or low-dose opioids (codeine or dihydrocodeine).

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree