Emergencies and Complications

Just the facts

Just the factsIn this chapter, you’ll learn:

♦ cardiac complications that require emergency measures

♦ pathophysiology and treatments related to these complications

♦ diagnostic tests, assessment findings, and nursing interventions for each complication.

A look at cardiac emergencies

Cardiac emergencies, which can result as a complication of another condition, require immediate assessment and treatment. They include cardiac trauma, cardiac tamponade, cardiogenic shock, and hypovolemic shock.

Cardiac trauma

Cardiac trauma, commonly dramatic in presentation, is usually associated with other thoracic injuries; it can occur as a result of blunt or penetrating trauma. Thoracic injuries—cardiac trauma included—account for about 20% to 25% of all trauma deaths and contribute to another 25% to 50% of the remaining deaths.1

|

Not always obvious

Although cardiac trauma can be severe, not all injuries are apparent on admission to the emergency department or intensive care unit, especially when the patient exhibits no external signs of chest wall damage. It may

be several hours before signs are noticeable, and several days before complications are evident. As a result, keen observation and assessment are essential for the early identification of cardiac injuries and potential complications.

be several hours before signs are noticeable, and several days before complications are evident. As a result, keen observation and assessment are essential for the early identification of cardiac injuries and potential complications.

The prognosis for a patient with cardiac trauma largely depends on the extent of the cardiac damage and his other injuries. Age and preexisting conditions also affect the prognosis.

What causes it

Cardiac trauma is a result of a blunt or penetrating chest injury.

How it happens

Blunt trauma typically results from vehicular accidents (70% to 80%)1 or falls from a great height, sport injuries, blast forces, and indirect compression on the abdomen with upward displacement of abdominal viscera. Rapid deceleration may result in shearing forces that tear cardiac structures and cause great vessel disruption. Falls may cause a rapid increase in intra-abdominal and intrathoracic pressures, which can result in myocardial rupture, valvular rupture, or both. Crushing and compression forces may result in contusion or rupture as the heart becomes compressed between the sternum and vertebral column. Blunt trauma commonly results in chest wall injuries (e.g., rib fractures). The pain associated with these injuries can make breathing difficult, and this may compromise ventilation.

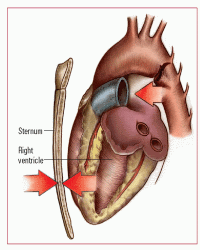

Cardiac concussion, a less severe form of blunt trauma, occurs when rapid deceleration causes the heart to strike the anterior chest wall and sternum, thereby resulting in myocardial contusion. (See Understanding myocardial contusion.)

Penetrating truths

Penetrating trauma to the heart, typically resulting from knife or gunshot wounds or foreign bodies in the heart, carries a high risk of mortality and usually requires immediate thoracotomy and surgical repair. This type of cardiac trauma commonly leads to cardiac tamponade. In 94% of cases involving penetrating cardiac trauma, death occurs before the patient reaches the hospital.

|

What to look for

Cardiac trauma may initially be overlooked as other life-threatening and more apparent injuries are treated. In addition, signs and symptoms of myocardial contusion or cardiac tamponade may not occur for several hours. Therefore, astute assessment skills are needed for early detection and prompt

treatment. A common practice involves serial cardiac biomarkers postadmission after a motor vehicle accident (MVA).

treatment. A common practice involves serial cardiac biomarkers postadmission after a motor vehicle accident (MVA).

Now I get it!

Now I get it!Understanding myocardial contusion

A myocardial contusion (bruising to the myocardium) is the most common type of injury sustained from blunt trauma. You should suspect it whenever a blow to the chest occurs. The contusion usually results from a fall or from impact with a steering wheel or other object. The right ventricle is the most common site of injury because of its location directly behind the sternum.

Here’s what happens:

• During deceleration injuries, the myocardium strikes the sternum as the heart and aorta move forward.

• In addition, the aorta may be lacerated by shearing forces.

• Direct force also may be applied to the sternum, causing injury.

|

Accident report

Typically, the patient with cardiac trauma is in pain and feels apprehensive. Attempt to ascertain the following information:

• mechanism of injury (e.g., in an automobile accident, include how the accident occurred, patient location in the vehicle and use of seat belts, and extent of internal car damage; for a fall, include how far the patient fell, onto what type of surface, and how he landed; for a gunshot wound, include the gun caliber and distance from which the patient was shot; for a stab wound, include the size and type of the weapon)

• history of cardiac or pulmonary problems

• pain location, onset, character, and severity

• presence of dyspnea.

Look for more

Other signs and symptoms associated with blunt trauma are:

• precordial chest pain

• bradycardia or tachycardia

• dyspnea

• contusion marks on the chest such as steering wheel imprint

• flail chest

• murmurs.

If the patient experienced penetrating trauma, look for:

• tachycardia

• shortness of breath with decreased breath sounds

• dullness upon percussion

• weakness

• diaphoresis

• acute anxiety

• cool, clammy skin

• upper extremity blood pressure differential or loss of upper or lower extremity pulses

• evidence of an external puncture wound or protrusion of the penetrating instrument

• symptoms of cardiac tamponade such as pulses paradoxus. For the patient who has a cardiac contusion, look for:

• hemodynamic instability such as severe or sudden hypotension

• arrhythmias caused by ventricular irritability

• heart failure or cardiogenic shock

• pericardial friction rub

• symptoms of cardiac tamponade.

If the patient is experiencing a cardiac concussion, many of the signs and symptoms listed above will be present.

|

What tests tell you

• Electrocardiogram (ECG) reveals rhythm disturbances, such as premature ventricular contractions, premature atrial contractions, ventricular tachycardia, atrial tachycardia, and ventricular fibrillation along with ischemic changes and nonspecific ST-segment or T-wave changes (with cardiac contusion) occurring within 48 hours after the injury.

• Chest X-ray shows widened mediastinum (with cardiac tamponade) and pulmonary edema (with septal defect). Thoracic computed tomography (CT) maybe an alternative to X-rays and may show associated injury of the great vessels or skeletal or pulmonary structures.

• An echocardiogram shows evidence of cardiac tamponade and valvular abnormalities, abnormal ventricular wall movement, and decreased ejection fraction (with myocardial contusion).

• Transesophageal echocardiogram shows evidence of aortic disruptions, cardiac tamponade, and atrial and septal defects.

• A multiple-gated acquisition (MUGA) scan detects decreased ability of effective heart pumping (with cardiac contusion).

• Cardiac enzyme levels show elevated creatine kinase (CK) levels; however, these rise with associated skeletal muscle injury. The usefulness of CK-MB is limited.2

• Cardiac troponin I shows elevations 24 hours after the injury (suggestive of cardiac injury).2 If troponin I results are within reference ranges on admission shortly after trauma, a secondary measurement after 4 to 6 hours is necessary to reliably exclude myocardial injury. Increased troponin I may persist for 4 to 6 days and may aid in evaluating cardiac damage of patients presenting days after the injury.

How it’s treated

Maintaining hemodynamic stability is crucial to the patient’s care. Penetrating trauma may be associated with massive hemorrhage leading to acute hypotension and shock. In addition, cardiac output is affected if the patient develops cardiac tamponade or arrhythmias occurring with myocardial contusion. Hemodynamic monitoring is key to evaluating the patient’s status and maintaining its adequacy. Intravenous (IV) fluid therapy, including blood component therapy, may be necessary. Continuous ECG monitoring is important to detect possible arrhythmias. Nearly all (81% to 95%) life-threatening ventricular arrhythmias and acute cardiac failures occur within 24 to 48 hours after the trauma.3 Amiodarone (Cordarone) may be used to treat ventricular arrhythmias. Digoxin (Lanoxin) may be given for pump failure. Inotropic agents may be used to assist with improving cardiac output and ejection fraction.

|

Look out for the lungs

The patient with cardiac trauma must be monitored closely for signs and symptoms of cardiopulmonary compromise because cardiac trauma is commonly associated with pulmonary trauma. Supplemental oxygen administration and assessment of oxygen saturation are important. If the degree of associated pulmonary trauma is great, endotracheal (ET) intubation and mechanical ventilation may be warranted to maintain adequate oxygenation.

Meds and other measures

If the patient is experiencing severe pain, IV morphine is administered in small amounts to the well-hydrated patient, unless the patient is hypotensive (in which case, other less potent analgesics are used). In addition, corrective surgery may be indicated to correct septal or valvular defects, penetrating injuries, or rupture. Emergency pericardiocentesis is used to treat acute cardiac tamponade.

What to do

• Collaborate care with a skilled team, which may include emergency medical services personnel, a surgeon, a respiratory therapist, and social services.

Cardiac check-in

• Assess the patient’s cardiopulmonary status at least every 4 hours—or more frequently, if indicated—to detect signs and symptoms of possible injury. Evaluate peripheral pulses and capillary refill to detect decreased peripheral tissue perfusion.

• Auscultate breath sounds at least every 4 hours, reporting signs of congestion or fluid accumulation.

• Monitor heart rate and rhythm, heart sounds, and blood pressure every hour for changes; institute hemodynamic monitoring—which may include mixed venous oxygen saturation, central venous pressure (CVP), pulmonary artery wedge pressure (PAWP), and continuous cardiac output as indicated—at least every 2 hours.

• Institute continuous cardiac monitoring for the first 48 to 72 hours to detect arrhythmias or conduction defects. If arrhythmias occur, administer antiarrhythmic agents as ordered and monitor electrolyte levels.

Fluids in and out

• Administer fluid replacement therapy, including blood component therapy as prescribed, typically to maintain systolic blood pressure above 90 mm Hg.

• Monitor urine output every hour, notifying the doctor if output is less than 30 ml/hour.

• Assess the patient’s degree of pain and administer analgesic therapy as ordered, monitoring for effectiveness. Position the patient comfortably, usually with the head of the bed elevated 30 to 45 degrees.

• Encourage coughing and deep breathing, splinting the chest as necessary.

• If the patient has undergone surgery, monitor and assess chest tubes for patency, volume and color of drainage, and presence of an air leak.

• Assess vital signs postoperatively, especially temperature.

• Inspect the surgical site for evidence of infection or bleeding at least every 4 hours, noting redness, drainage, warmth, edema, or localized pain at the site.

Outside help

• Arrange for possible social service consultation depending on the cause of the injury—for example, alcohol-related automobile accident or gang-related gunshot injury.

• Provide brief explanations about the patient’s condition and why it’s occurring. Inform the patient and his family about how the condition will be treated, being sure to explain new procedures before beginning them.

• Review signs and symptoms of a worsening condition, stressing the importance of alerting the nurse if any occur.

• Teach the patient about signs and symptoms of complications and the need for follow-up.

• Document vital signs and assessment findings. Document the patient’s response to treatment.

Cardiac tamponade

Cardiac tamponade is a rapid, unchecked increase in pressure within the pericardial sac. This pressure compresses the heart, impairs diastolic filling, and reduces cardiac output.

The increase in pressure usually results from blood or fluid accumulation in the pericardial sac. Even a small amount of fluid (50 to 100 ml) can cause a serious tamponade if it accumulates rapidly.

|

Quick fill, quick response

If fluid accumulates rapidly, cardiac tamponade requires emergency lifesaving measures to prevent death. A slow accumulation and increase in pressure may not produce immediate symptoms because the fibrous wall of the pericardial sac can gradually stretch to accommodate as much as 1 to 2 L of fluid.

What causes it

Cardiac tamponade may result from:

• idiopathic causes (such as Dressler’s syndrome)

• effusion (from cancer, bacterial infections, tuberculosis and, rarely, acute rheumatic fever),4 the most common cause of >50% of all tamponade cases

• hemorrhage caused by trauma (such as gunshot or stab wounds of the chest)

• hemorrhage caused by nontraumatic causes (such as anticoagulant therapy in patients with pericarditis or rupture of the heart or great vessels)

• viral or postirradiation pericarditis

• chronic renal failure requiring dialysis

• drug reaction from procainamide, hydralazine, minoxidil, isoniazid, penicillin, or daunorubicin

• connective tissue disorders (such as rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatic fever, and scleroderma)

• acute myocardial infarction (MI)

• postcardiac procedures such as percutaneous coronary interventions, pacemaker or implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) insertion, open-heart surgery, or cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR).

How it happens

In cardiac tamponade, accumulation of fluid in the pericardial sac causes compression of the heart chambers. This compression obstructs blood flow into the ventricles and reduces the amount of blood that can be pumped out of the heart with each contraction. (See Understanding cardiac tamponade.)

That’s not all

Other signs include:

• narrowed pulse pressure

• orthopnea

• diaphoresis

• anxiety or confusion

• restlessness

• cyanosis

• weak, rapid peripheral pulse.

What tests tell you

• Chest X-ray shows a slightly widened mediastinum and an enlarged cardiac silhouette.

• ECG may show a low-amplitude QRS complex and electrical alternans, an alternating beat-to-beat change in amplitude of the P wave, QRS complex, and T wave. Generalized ST-segment elevation is noted in all leads. An ECG is used to rule out other cardiac disorders; it may reveal changes produced by acute pericarditis.

Now I get it!

Now I get it!Understanding cardiac tamponade

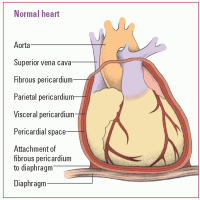

The pericardial sac, which surrounds and protects the heart, is composed of several layers:

• The fibrous pericardium is the tough outermost membrane.

• The inner membrane, called the serous membrane, consists of the visceral and parietal layers.

• The visceral layer clings to the heart and is also known as the epicardial layer of the heart.

• The parietal layer lies between the visceral layer and the fibrous pericardium.

|

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree