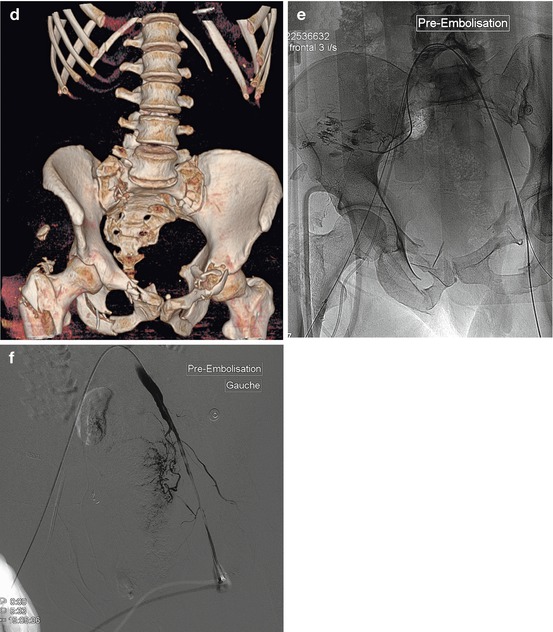

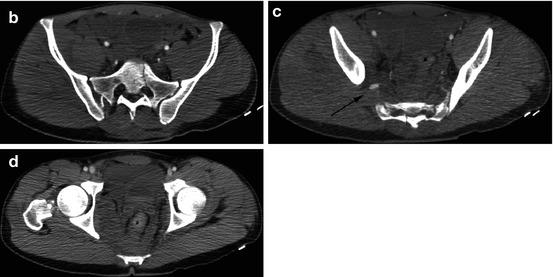

Fig. 21.1

Fifty-one-year-old male admitted with a very serious hemodynamic shock, after defenestration from 3rd floor. The mobile emergency medical unit (SAMU) conducted him directly to the CT room for a complete morphological assessment, because of multiple traumatic impacts, especially to the abdomen and pelvis. (a) Chest plain film: fractures of the right humeral head, thoracic flail, limited hemopneumothorax, and subcutaneous emphysema. (b) Hepatic blush; multiple foci of contusion of the liver. Enhancement of the kidneys and the spleen was decreased, but without apparent focal injury. (c) Multiple pelvic fractures, intrapelvic hematomas with blushes. (d) MPR reconstruction of the pelvis: multiple fractures. The critical hemodynamic status led the patient directly to the angiography room. (e) After bilateral femoral artery punctures (as pulse were even perceptible), aortography enabled a selective catheterization by crossover of the right and left internal iliac arteries. The selective injection of the right gluteal artery shows multiple extravasations that were treated by embolization with coils + gelatin. Extravasation in the anterior branches territories was also treated with coils. (f) Selective injection at the end of the left common iliac artery (from a right femoral access and crossover): massive vasoconstriction of the entire internal iliac network. The presence of a blush on the CT led us to inject resorbable gelatin in the trunk of the left hypogastric artery. (g) Left external iliac artery opacification: extravasation from the external iliac circumflex artery, a branch of the common femoral artery (arrow). (h) Selective catheterization of the iliac circumflex artery: massive extravasation, treated with coils. At this moment, the patient remained hemodynamically unstable, with abundant hemoperitoneum on ultrasound performed on the angio table: the opacification of the visceral arterial branches was then decided. (i) Abdominal aortography: vasoconstriction of renal and splanchnic arterial territories. Extravasation in the liver (arrow). (j) Selective catheterization of the common hepatic artery, which confirms massive blush in segment VIII. (k) Control injection after exclusion by particles and coils

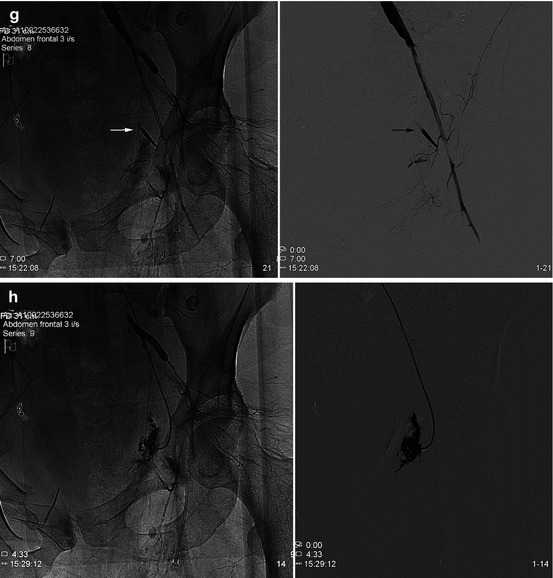

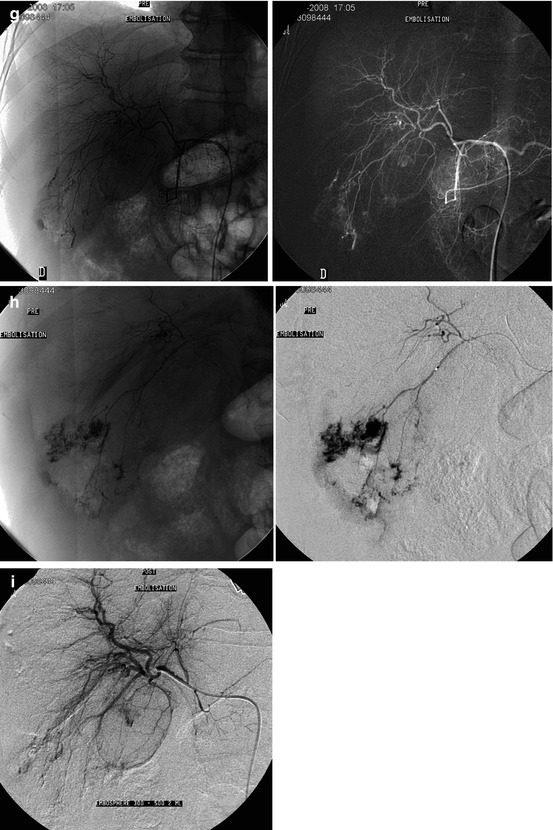

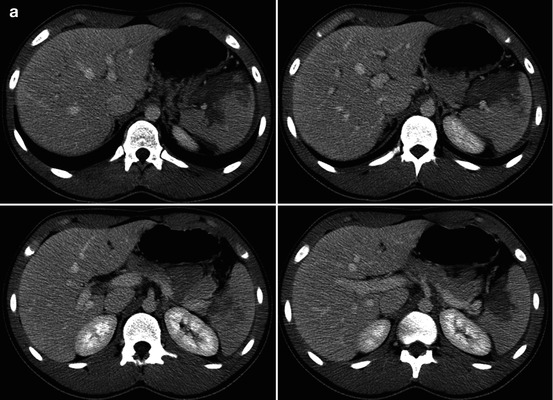

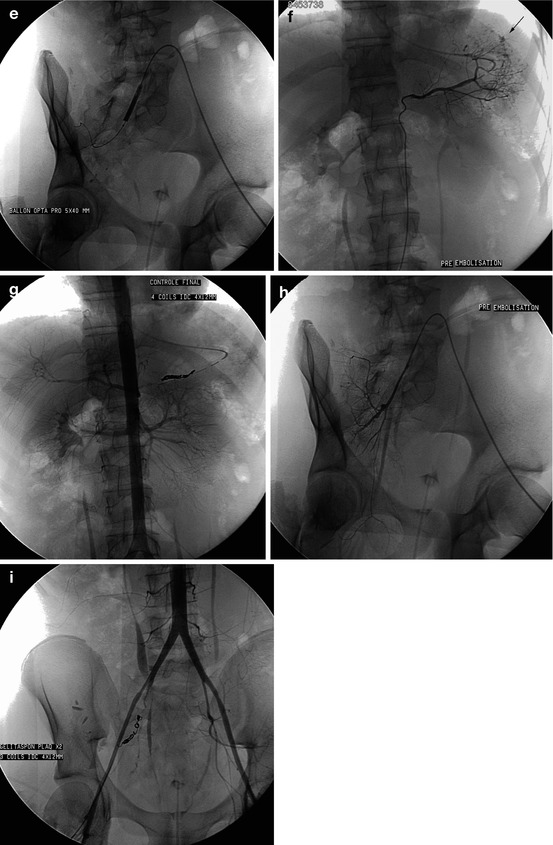

Fig. 21.2

Forty-six-year-old male, 8 m fall. (a–d) Initial CT: D12 fracture, pelvic fractures with large asymmetric pelvic hematoma; focal right renal contusion, important liver injury with blush. (e) Exclusion by coils of the right hypogastric artery because of multiple extravasations of anterior and posterior branches. (f) Selective injection of the right renal artery: no extravasation (no embolization). (g) Selective injection of the hepatic artery: diffuse vasoconstriction; important extravasation in segment VI, considered as the cause of the hemoperitoneum. (h) Hyperselective catheterization. (i) Control opacification after hyperselective exclusion by microparticles

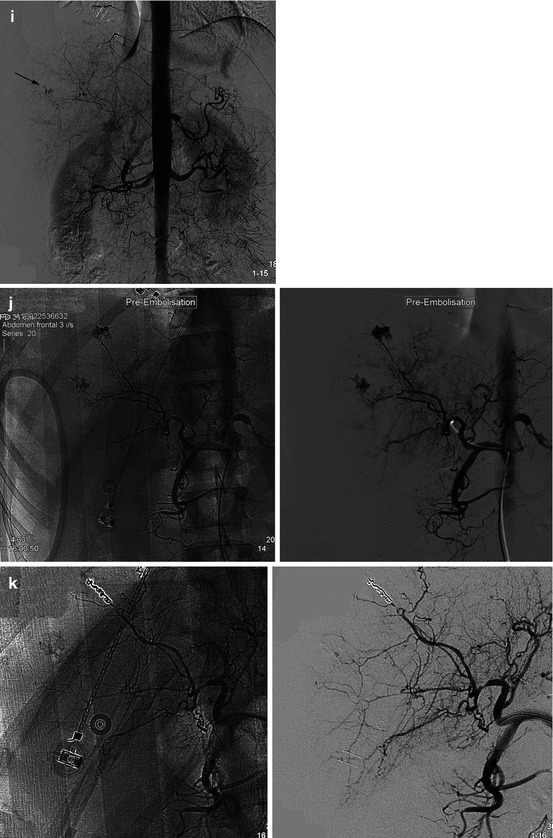

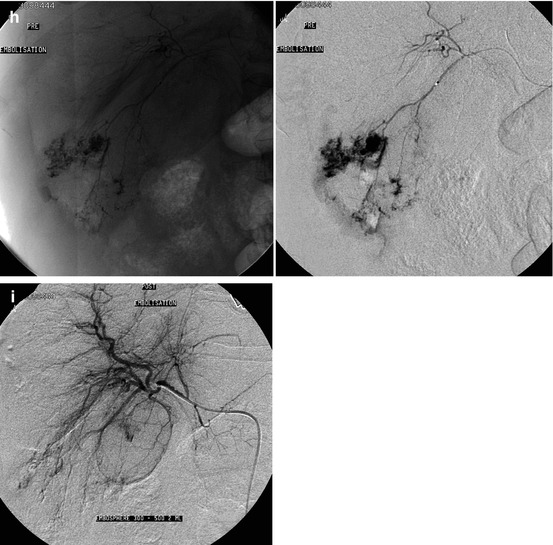

Fig. 21.3

Fall from horse: fracture of the left humerus, rib fractures, limited left pleural effusion, and left upper quadrant pain. (a) Intraperitoneal effusion (Morison pouch: white arrow), associated with a left limited perirenal hematoma (black arrow), with a blush localized in the sinus. The hemodynamic stability has led to abstention. (b) Four days later, during surveillance: abundant hematuria with deglobulization. New CT: the retroperitoneal effusion is partially absorbed; the perirenal hematoma had not significantly increased in size, but the parenchymal blush with the synchronous enhancement of the renal pelvis was suggestive of arterio-calyceal fistula. (c) Aortography: opacification of a left intrarenal arterialized cavity. (d) Hyperselective injection into the retro pelvic artery: this artery does not participate to the vascularization of the traumatic lesion. (e, f) Semi-selective injection of the pre-pelvic artery: the first-order arterial branch supplies the traumatic cavity. (g) Control opacification after exclusion by coils of the arterial branch feeding the arterio-calyceal fistula

Fig. 21.4

Fall from bike with parietal cephalic impacts and abdominal pain: collapse. Brain CT was normal. (a) Abdominal CT: AAST III trauma of the spleen. (b) Frontal CT reconstruction. (c) Selective catheterization of the celiac trunk: displacement of the intrasplenic arterial tree, but without any obvious extravasation. (d) Hyperselective catheterization of the superior lobar branch, which shows a blush with extravasation. (e) Control opacification after exclusion by microcoils + gelatin of the inferior division branch of the superior lobar artery. (f) CT scan 6 months later, while the immediate aftermath and the clinical course were very simple: despite the artifacts caused by coils, the spleen appears correctly perfused

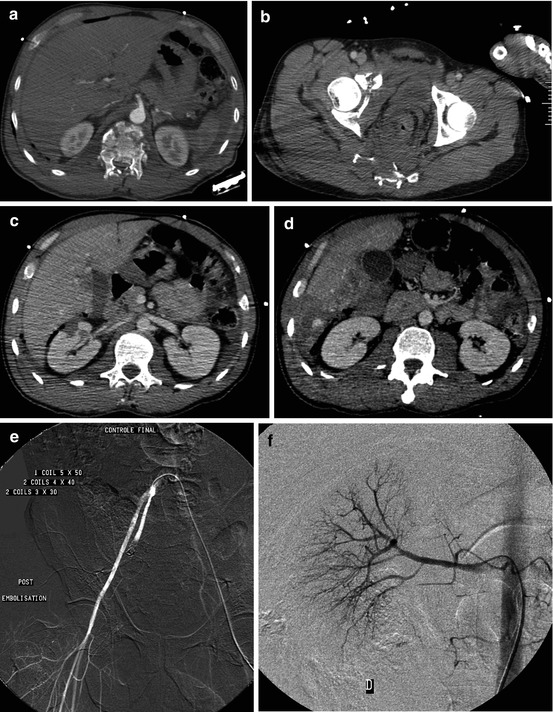

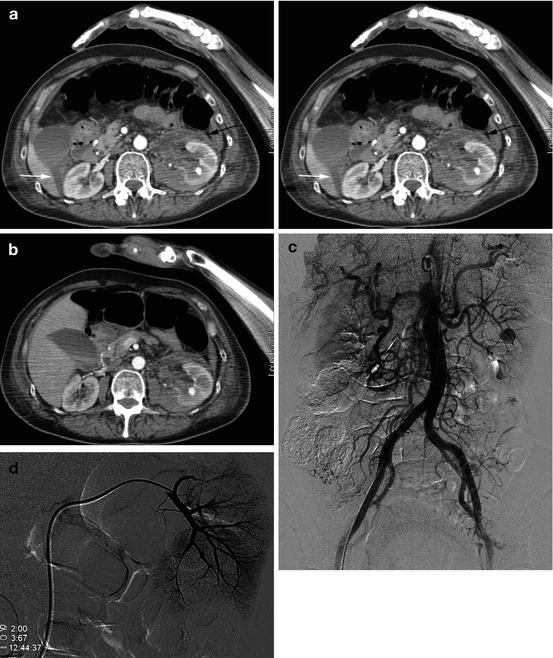

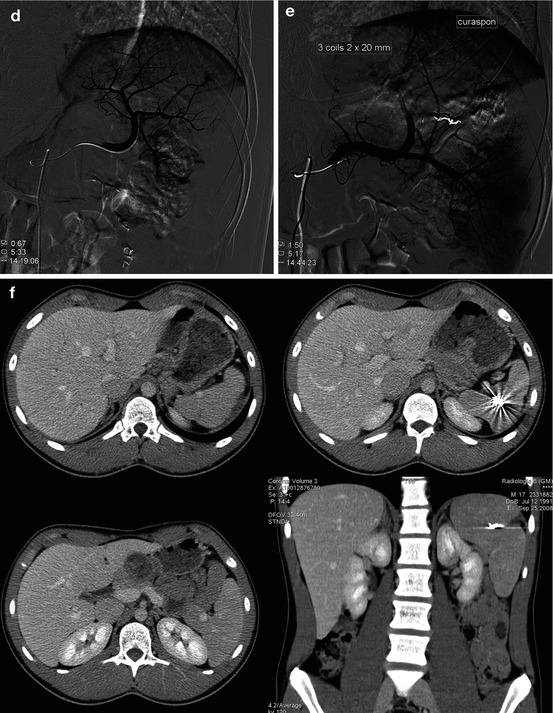

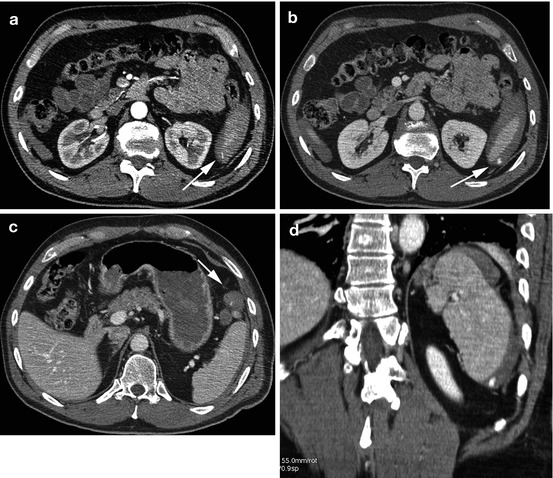

Fig. 21.5

Seventeen-year-old, ATV accident with head trauma without loss of consciousness; trauma to the chest, abdomen, pelvis, and left lower limb: hemodynamic collapse. Besides a fracture of the left femur, brain and spinal CT does not retain any lesion of concern. A diffuse bronchioloalveolar condensation of the left base was also noted. (a) Hemoperitoneum caused by a AAST grade IV–V splenic injury. (b) Multiple fractures of the sacrum and the ischiopubic branches with blush, consequence of the injury of the gluteal artery (c), responsible for an important intrapelvic hematoma. (d) An endovascular treatment was decided. (e) After arteriographic verification of the superficial femoral arteries, the localization of the arterial traumatic lesion at the right buttock has led to an initial balloon occlusion of the internal iliac artery, followed by a rapid hemodynamic stabilization. We then carried on the spleen trauma. (f) The splenic artery is selectively catheterized: a significant blush was found at the upper pole, leading to exclusion by resorbable gelatin supplemented by truncal coils (g). (h) The selective injection of the right hypogastric artery showed extravasations not only in the territory of the gluteal artery but also from intrapelvic arterial branches, leading to coil embolization (i) supplemented with gelatin in the hypogastric artery

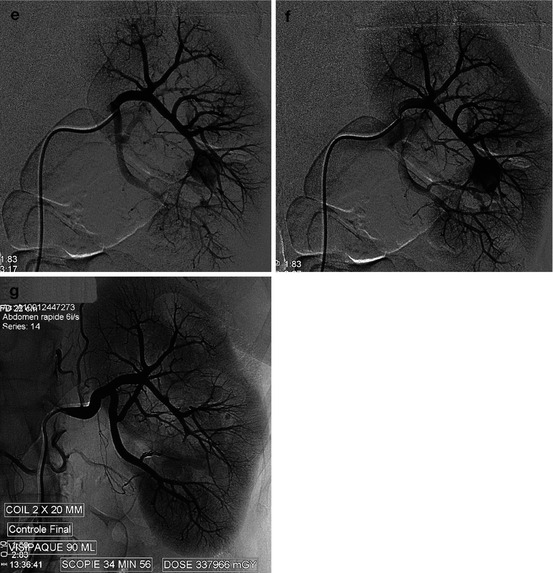

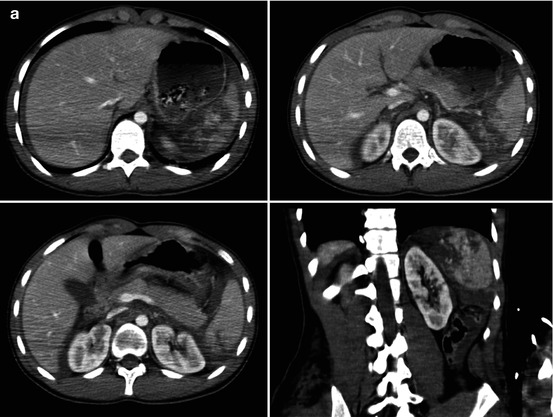

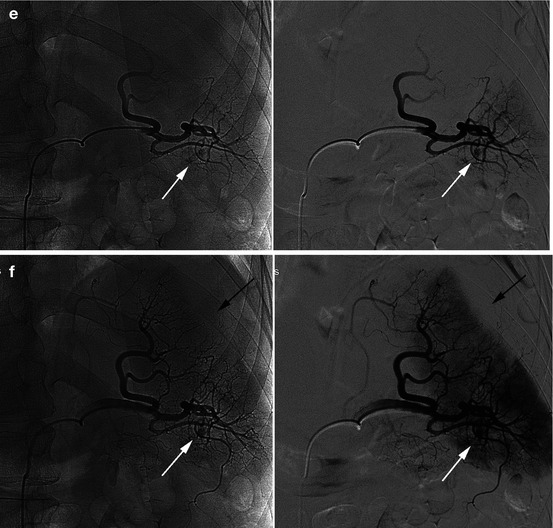

Fig. 21.6

Forty-nine-year-old; highway accident with limb fractures, basi-thoracic and left hypochondrial impact. (a–d) CT, AAST III splenic traumatic injury (ruptured subcapsular hematoma + blush); coronal reconstruction: no evident parenchymal lesion, but a ruptured subcapsular hematoma (arrow). (e–f) Selective injection of the splenic artery: modal distribution of branches. We found an inferomedial blush (white arrow), while the external contours of the spleen are deformed (black arrow). Hyperselective catheterization by micro-catheters led to the exclusion by coils + gelatin + particles (hyperselective control). (g–h) Semi-selective control after embolization

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree