Guidelines recommend lifestyle modification for patients with coronary heart disease (CHD). Few data demonstrate which lifestyle modifications, if sustained, reduce recurrent CHD and mortality risk in cardiac patients after the postacute rehabilitation phase. We determined the association between ideal lifestyle factors and recurrent CHD and all-cause mortality in REasons for Geographic and Racial Differences in Stroke study participants with CHD (n = 4,174). Ideal lifestyle factors (physical activity ≥4 times/week, nonsmoking, highest quartile of Mediterranean diet score, and waist circumference <88 cm for women and <102 cm for men) were assessed through questionnaires and an in-home study visit. There were 447 recurrent CHD events and 745 deaths over a median 4.3 and 4.5 years, respectively. After multivariable adjustment, physical activity ≥4 versus no times/week and non-smoking versus current smoking were associated with reduced hazard ratios (HRs; 95% confidence interval [CI]) for recurrent CHD (HR 0.69, 95% CI 0.54 to 0.89 and HR 0.50, 95% CI 0.39 to 0.64, respectively) and death (HR 0.71, 95% CI 0.59 to 0.86 and HR 0.53, 95% CI 0.44 to 0.65, respectively). The multivariable-adjusted HRs (and 95% CIs) for recurrent CHD and death comparing the highest versus lowest quartile of Mediterranean diet adherence were 0.77 (95% CI 0.55 to 1.06) and 0.84 (95% CI 0.67 to 1.07), respectively. Neither outcome was associated with waist circumference. Comparing participants with 1, 2, and 3 versus 0 ideal lifestyle factors (non-smoking, physical activity ≥4 times/week, and highest quartile of Mediterranean diet score), the HRs (and 95% CIs) were 0.60 (95% CI 0.44 to 0.81), 0.49 (95% CI 0.36 to 0.67), and 0.38 (95% CI 0.21 to 0.67), respectively, for recurrent CHD and 0.65 (95% CI 0.51 to 0.83), 0.57 (95% CI 0.43 to 0.74), and 0.41 (95% CI 0.26 to 0.64), respectively, for death. In conclusion, maintaining smoking cessation, physical activity, and Mediterranean diet adherence is important for secondary CHD prevention.

Although lifestyle modification has clear benefits and is recommended for secondary prevention of coronary heart disease (CHD), <20% of cardiac patients complete cardiac rehabilitation programs. Few data demonstrate which secondary prevention lifestyle modifications, if sustained after the postacute CHD event period, reduce the risk for recurrent CHD or all-cause mortality. Additionally, the long-term CHD risk reduction benefits of multiple lifestyle factors have not been extensively studied. Therefore, we determined the association of (1) ideal levels of individual lifestyle factors that are the focus of cardiac rehabilitation programs, including waist circumference, physical activity, adherence to a Mediterranean diet, and smoking status, and (2) multiple ideal lifestyle factors with recurrent CHD and all-cause mortality. Determining these associations with recurrent CHD events and all-cause mortality can justify maintaining lifestyle modifications for secondary prevention and reinforce current guidelines. To do so, we analyzed a large population-based cohort of adults in the United States with existent CHD enrolled in the REasons for Geographic and Racial Differences in Stroke (REGARDS) study.

Methods

The REGARDS study has been described previously. In brief, 30,239 adults aged ≥45 years from all 48 continental states of the United States and the District of Columbia were enrolled from January 2003 to October 2007. By design, the REGARDS study oversampled blacks and residents of Southeastern United States (North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, Tennessee, Arkansas, and Louisiana). The current analysis was restricted to REGARDS participants reporting a history of CHD (defined in the following) at baseline and having recurrent CHD follow-up data (n = 4,174). Each participating center’s Institutional Review Board governing human subject research approved the REGARDS study protocol. All participants provided informed consent.

Baseline data were collected through a telephone interview, self-administered questionnaires, and an in-home examination. During computer-assisted telephone interviews administered by trained staff, participants’ age, race, gender, smoking status, education, annual household income, physical activity, self-rated health, regular aspirin use, and self-report of previous diagnosed co-morbid conditions (e.g., diabetes, myocardial infarction, coronary revascularization procedures) were collected. Because awareness of a CHD event could prompt behavior changes, history of CHD was defined as self-reported myocardial infarction, angioplasty or stenting of a coronary artery, or coronary bypass surgery. During the in-home examination, technicians measured waist circumference and blood pressure (BP) and collected blood and spot urine samples (described previously). Prescription and over-the-counter pill bottles were reviewed for medications taken during the 2 weeks before the in-home study visit. The use of clopidogrel, β blockers, statins, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, and angiotensin receptor blockers were considered in this analysis. After the in-home examination, participants completed and mailed a self-administered Block 98 Food-Frequency Questionnaire to the coordinating center.

Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol was calculated using the Friedewald equation. Diabetes was defined by self-report with concurrent use of insulin or oral hypoglycemic medications or fasting serum glucose ≥126 mg/dl or nonfasting serum glucose ≥200 mg/dl. High-sensitivity C-reactive protein was measured by particle-enhanced immunonephelometry. Estimated glomerular filtration rate was calculated using the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration equation. Reduced estimated glomerular filtration rate was defined as levels <60 ml/min/1.73 m 2 . Albuminuria was defined as urinary albumin/urinary creatinine ratio ≥30 mg/g.

Four lifestyle factors were evaluated: abdominal obesity, physical activity, adhering to a Mediterranean-style diet, and cigarette smoking. Compared with body mass index, waist circumference has been shown to have a stronger association with cardiovascular (CV) events and, thus, was chosen as a measure of adiposity in the current analysis. Abdominal obesity was defined as a waist circumference of >102 cm and >88 cm for men and women, respectively. Physical activity was assessed with the question “How many times per week do you engage in intense physical activity, enough to work up a sweat?” Response options were “none,” “1 to 3,” or “≥4” times per week. The Food-Frequency Questionnaire was processed with NutritionQuest software to estimate the average dietary nutrient intake for 1 year before participants’ in-home visit. A Mediterranean diet score was created with 14 all-inclusive food groups and nutrients (e.g., potatoes, vegetables, legumes, fruits and nuts, dairy products, cereals, meats, fish, eggs, monounsaturated lipids, polyunsaturated lipids, saturated lipids and margarines, sugar and sweets, nonalcoholic beverages), using a monounsaturated/saturated fats ratio similar to methods described by Trichopoulou et al. Participants were grouped into quartiles based on the study population’s distribution of Mediterranean diet scores (cut points: ≤3, 4 to <5, 5, and ≥5 [higher quartiles: better adherence]). Current smoking was defined as responding “yes” to both questions: “Have you smoked at least 100 cigarettes in your lifetime?” and “Do you smoke cigarettes now, even occasionally?” Ideal lifestyle factors were (1) not having abdominal obesity, (2) physical activity ≥4 times/week, (3) Mediterranean diet score in the highest quartile, and (4) being a nonsmoker.

Two outcomes were studied: recurrent CHD or all-cause mortality. After the baseline visit, living participants or their proxies were contacted biannually by way of telephone to assess potential recurrent CHD events and vital status. When a CHD-related hospitalization or a death was reported, medical records were retrieved and trained clinicians adjudicated events following published guidelines. Online sources (e.g., Social Security Death Index), the National Death Index, and reports from next of kin were used to detect participant deaths. Circumstances of the death were obtained by interviewing proxies or next of kin, from death certificates, autopsy reports, and medical records. Definite or probable CHD events (nonfatal myocardial infarction or acute CHD death) and all-cause mortality through December 31, 2009 were analyzed.

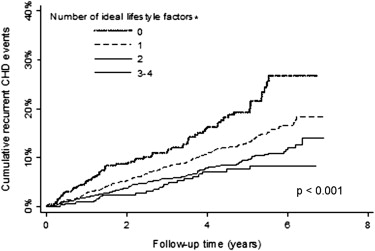

Participant characteristics were calculated by number of ideal lifestyle factors (0, 1, 2, or ≥3). Crude rates for recurrent CHD were calculated for levels of each lifestyle factor. Cox proportional hazard models with progressive adjustment were used to calculate the hazard ratios (HRs) for recurrent CHD associated with each lifestyle factor. An initial model (model 1) included adjustment for age, gender, race, and geographic region of residence. A second model (model 2) included additional adjustment for low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, BP, education, annual household income, self-rated health, diabetes, albuminuria, estimated glomerular filtration rate, C-reactive protein, and use of aspirin, clopidogrel, β blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers, and statins. Next, the cumulative incidence of recurrent CHD was calculated by number of ideal lifestyle factors (physical activity ≥4 times/week, highest quartile of Mediterranean diet adherence, and nonsmoking). As waist circumference was not associated with recurrent CHD or all-cause mortality, it was excluded from the analysis of number of ideal lifestyle factors. Cumulative incidence curves were plotted by number of ideal lifestyle factors. HRs for recurrent CHD associated with the number of ideal lifestyle factors were calculated with similar adjustment as described previously. Identical analyses were repeated for all-cause mortality. Missing data were imputed with 10 data sets using chained equations. The number (%) of imputed lifestyle factors were waist circumference: 28 (0.7%), physical activity: 62 (1.5%), smoking: 12 (0.3%), and Mediterranean diet score: 1,355 (32.5%). Analyses were conducted using Stata/IC 12.1 (Stata Corporation, College Station, Texas).

Results

The mean age and the proportion of participants taking aspirin and statins were higher in those with more ideal lifestyle factors ( Table 1 ). Women and blacks were less likely to have more ideal lifestyle factors. The percentage of participants with less than a high school education, an annual household income <$20,000, albuminuria, and diabetes was lower with more ideal lifestyle factors. The mean systolic and diastolic BP, waist circumference, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, and C-reactive protein were lower as the number of ideal lifestyle factors increased. Other participant characteristics were similar across the number of ideal lifestyle factors.

| Participant characteristic | Number of Ideal Lifestyle Factors † | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 (n = 240) | 1 (n = 1,383) | 2 (n = 1,452) | 3 – 4 (n = 1,100) | |

| Percentage of sample | 5.7% | 33.1% | 34.8% | 26.4% |

| Age (years) | 64.8 (0.5) | 67.2 (0.3) | 69.7 (0.3) | 70.4 (0.3) |

| Female | 57.1% | 47.2% | 32.5% | 21.6% |

| Black | 40.9% | 39.8% | 33.9% | 25.9% |

| Less than a high school education | 25.1% | 20.0% | 17.0% | 12.5% |

| Household Income <$20,000 | 37.3% | 28.8% | 20.2% | 12.7% |

| Geographic Region | ||||

| Stroke belt | 36.4% | 35.3% | 34.1% | 33.5% |

| Stroke buckle | 18.9% | 21.5% | 22.2% | 20.4% |

| Other region | 44.7% | 43.2% | 43.7% | 46.1% |

| Diabetes mellitus | 46.9% | 45.4% | 33.2% | 23.9% |

| Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 130.9 (1.2) | 131.6 (0.5) | 129.5 (0.5) | 128.0 (0.6) |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 75.8 (0.6) | 76.1 (0.3) | 75.0 (0.3) | 74.0 (0.3) |

| Low estimated GFR (<60 ml/min/1.73 m 2 ) | 22.1% | 24.4% | 25.1% | 17.1% |

| High albumin to creatinine ratio (≥30 mg/g) | 32.2% | 28.7% | 23.9% | 17.4% |

| Aspirin Use | 74.6% | 74.4% | 75.0% | 82.6% |

| Clopidogrel Use | 20.0% | 19.0% | 19.5% | 17.2% |

| Statin Use | 58.2% | 62.3% | 65.7% | 68.6% |

| Beta blocker use | 55.3% | 53.9% | 53.1% | 51.9% |

| ACE inhibitor use | 44.4% | 39.9% | 40.1% | 36.8% |

| Angiotensin receptor blocker use | 15.2% | 22.2% | 18.3% | 15.8% |

| Abdominal obesity ∗ | 100.0% | 86.8% | 44.1% | 12.2% |

| Serum LDL-cholesterol (mg/dL) | 103.5 (2.6) | 100.6 (1.0) | 98.7 (1.0) | 95.1 (1.1) |

| C-reactive protein mg/L | 4.8 (4.7 – 4.9) | 3.3 (3.2 – 3.3) | 2.4 (2.4 – 2.4) | 1.6 (1.6 – 1.6) |

∗ Abdominal obesity = waist circumference for men: >102 cm and women: >88 cm.

† Ideal lifestyle factors were defined as not having abdominal obesity, physical activity ≥4 times per week, Mediterranean diet score in the highest quartile, and being a non-smoker.

The prevalence of ideal waist circumference, physical activity ≥4 times/week, high Mediterranean diet adherence, and nonsmoking was 46.9%, 30.1%, 25.4%, and 84.6%, respectively. There were 447 recurrent CHD events over a median follow-up of 4.3 years (maximum 6.9). Incidence of recurrent CHD was lower in subjects with higher levels of physical activity, higher Mediterranean diet adherence, and nonsmokers ( Table 2 ). Recurrent CHD rates were not substantially different for subjects with and without abdominal obesity. The HRs for recurrent CHD were lower for subjects participating in physical activity 1 to 3 or ≥4 times/week versus no physical activity, subjects more adherent to a Mediterranean diet, and nonsmokers versus current smokers after adjustment for age, race, gender, and region of residence. Although participating in physical activity 1 to 3 or ≥4 times/week and not smoking remained associated with a lower HR for recurrent CHD after multivariable adjustment, the HR comparing the highest with the lowest quartile of Mediterranean diet score was no longer statistically significant.

| Individual lifestyle factors | Events/persons at risk | Incidence Rate (95% CI) | Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crude (per 1,000 person-years) | Model 1 | Model 2 | ||

| Abdominal obesity † | ||||

| Yes | 241/2,215 | 27.2 (23.7 – 30.6) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| No | 206/1,959 | 25.7 (22.2 – 29.2) | 0.88 (0.73 – 1.07) | 1.07 (0.87 – 1.31) |

| p-value | – | – | 0.207 | 0.503 |

| Physical Activity | ||||

| None | 225/1,611 | 36.7 (31.8 – 41.5) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| 1 – 3 times/week | 119/1,308 | 21.6 (17.7 – 25.6) | 0.59 (0.47 – 0.75) | 0.72 (0.57 – 0.90) |

| 4+ times/week | 104/1,255 | 19.7 (15.9 – 23.5) | 0.53 (0.42 – 0.68) | 0.69 (0.54 – 0.89) |

| p-trend | – | – | <0.001 | 0.002 |

| Mediterranean diet score ‡ | ||||

| Quartile 1 (lowest – worse score) | 175/1,385 | 32.2 (26.8 – 37.6) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| Quartile 2 | 91/884 | 25.5 (19.2 – 37.8) | 0.79 (0.60 – 1.03) | 0.85 (0.65 – 1.12) |

| Quartile 3 | 85/845 | 24.1 (18.1 – 30.2) | 0.73 (0.53 – 1.03) | 0.76 (0.54 – 1.07) |

| Quartile 4 (highest – better score) | 96/1,060 | 21.9 (16.9 – 26.9) | 0.66 (0.48 – 0.90) | 0.77 (0.55 – 1.06) |

| p-trend | – | – | 0.011 | 0.084 |

| Current Smoker | ||||

| Yes | 102/642 | 43.9 (35.4 – 52.4) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| No | 345/3,532 | 23.7 (21.2 – 26.2) | 0.47 (0.37 – 0.56) | 0.50 (0.39 – 0.64) |

| p-value | – | – | <0.001 | <0.001 |

† Abdominal obesity = waist circumference >102 cm for men, >88 cm for women.

‡ The cut-points for the lowest to highest quartile of the Mediterranean diet scores were ≤3, >3 to 4, >4 to 5, and >5.

Over a median follow-up of 4.5 years (maximum 6.9), 745 deaths occurred. More physical activity, higher Mediterranean diet adherence, and not smoking were associated with lower crude rates and age-, race-, gender-, and region of residence–adjusted HRs for mortality ( Table 3 ). More physical activity and not smoking remained associated with lower HRs for death after full multivariable adjustment. The highest Mediterranean diet quartile was no longer significantly associated with mortality after multivariable adjustment. Abdominal obesity was not associated with mortality before or after multivariable adjustment.

| Individual lifestyle factors | Events/persons at risk | Incidence Rate (95% CI) | Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crude (per 1,000 person-years) | Model 1 | Model 2 | ||

| Abdominal obesity † | ||||

| Yes | 382/2,215 | 41.8 (37.6 – 46.0) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| No | 363/1,959 | 43.7 (39.2 – 48.2) | 0.93 (0.80 – 1.08) | 1.15 (0.98 – 1.35) |

| p-value | – | – | 0.320 | 0.090 |

| Physical Activity | ||||

| None | 409/1,613 | 64.0 (57.8 – 70.2) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| 1 – 3 times/week | 166/1,308 | 29.2 (24.7 – 33.7) | 0.48 (0.40 – 0.58) | 0.61 (0.50 – 0.73) |

| 4+ times/week | 171/1,254 | 31.7 (26.9 – 36.5) | 0.50 (0.42 – 0.61) | 0.71 (0.59 – 0.86) |

| p-trend | – | – | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Mediterranean diet score ‡ | ||||

| Quartile 1 (lowest – worse score) | 274/1,385 | 48.3 (42.3 – 54.3) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| Quartile 2 | 165/884 | 45.6 (37.8 – 53.4) | 0.92 (0.75 – 1.14) | 1.02 (0.82 – 1.27) |

| Quartile 3 | 145/845 | 40.0 (32.0 – 48.0) | 0.78 (0.61 – 1.00) | 0.83 (0.63 – 1.08) |

| Quartile 4 (highest – better score) | 161/1,060 | 35.6 (29.4 – 41.7) | 0.68 (0.55 – 0.86) | 0.84 (0.66 – 1.07) |

| p-trend | – | – | <0.001 | 0.061 |

| Current Smoker | ||||

| Yes | 156/642 | 63.4 (53.4 – 73.3) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| No | 589/3,532 | 39.3 (36.1 – 42.5) | 0.46 (0.38 – 0.55) | 0.53 (0.44 – 0.65) |

| p-value | – | – | <0.001 | <0.001 |

† Abdominal obesity = waist circumference >102 cm for men, >88 cm for women.

‡ The cut-points for the lowest to highest quartile of the Mediterranean diet scores were ≤3, >3 to 4, >4 to 5, and >5.

The prevalence of 0, 1, 2, or 3 ideal lifestyle factors (i.e., physical activity ≥4 times/week, Mediterranean diet in the highest quartile, non-smoking) was 10.1%, 48.2%, 33.2%, and 8.5%, respectively. The cumulative incidence for recurrent CHD and mortality were each lower with progressively more ideal lifestyle factors ( Figures 1 and 2 ). These associations remained present after multivariable adjustment ( Tables 4 and 5 ).