Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) prevalence is greater in racially/ethnically diverse groups compared with non-Hispanic white populations. Although race has been shown to modify other cardiovascular disease risk factors in postpartum women, the role of race/ethnicity on GDM and subsequent hypertension has yet to be examined. The aim of this study was to evaluate the impact of race/ethnicity in relation to GDM and subsequent hypertension in a retrospective analysis of women who delivered at Massachusetts General Hospital from 1998 to 2007. Multivariate analyses were used to determine the associations between GDM and (1) race/ethnicity, (2) hypertension, and (3) the interaction with hypertension and race/ethnicity. Women were monitored for a median of 3.8 years from the date of delivery. In our population of 4,010 women, GDM was more common in nonwhite participants (p <0.0001). GDM was also associated with hypertension subsequent to delivery after adjusting for age, race, parity, first-trimester systolic blood pressure, body mass index, maternal gestational weight gain, and preeclampsia (hazard ratio [HR] 1.75, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.28 to 2.37, p = 0.0004). Moreover, Hispanic (HR 3.25, 95% CI 1.85 to 5.72, p <0.0001) and white (HR 1.68, 95% CI 1.10 to 2.57, p = 0.02) women with GDM had greater hypertension risk relative to their race/ethnicity–specific counterparts without GDM in race-stratified multivariable analyses. In conclusion, Hispanic women compared with white women have an increased risk of hypertension. Hispanic and white women with GDM are at a greater risk for hypertension compared with those without GDM. Because the present study may have had limited power to detect effects among black and Asian women with GDM, further research is warranted to elucidate the need for enhanced hypertension risk surveillance in these young women.

Several studies report that gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) prevalence is greater in racially/ethnically diverse populations compared with non-Hispanic white populations. For example, the prevalence of GDM in women in the United States has been reported as 7.4% in Asian, 3.9% in Hispanic, 3.1% in non-Hispanic black, and 2.4% in non-Hispanic white populations. Although race has been shown to modify other cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk factors such as type 2 diabetes and the metabolic syndrome, the role of race/ethnicity in mediating the relation between GDM and hypertension risk has not been fully examined. Consequently, our investigation tests the hypothesis that a population of women with clinically confirmed GDM will demonstrate an increased risk of future hypertension, independent of the development of type 2 diabetes. Furthermore, we hypothesize that in nondiabetic women with a history of GDM, the association between GDM and hypertension will be greater in nonwhite compared with white women.

Methods

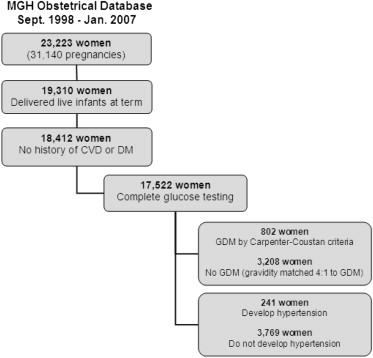

We conducted a retrospective study of women who presented for prenatal care to the Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) Obstetrical Department from September 1998 to January 2007. These 23,223 women (representing 31,140 pregnancies) were subsequently included in the study population if they delivered full-term (gestational age ≥37 weeks) live infants (n = 19,310); had no history of pregestational diabetes; had no history of CVD before delivery, including cerebrovascular disease, ischemic heart disease, or hypertension as identified by medical record review and International Classification of Diseases, ninth revision (ICD-9), codes (n = 18,412); and had complete third-trimester (24 to 28 weeks gestational age) biochemical data to diagnose GDM, including a 1-hour glucose load test and a 3-hour oral glucose tolerance test with complete data available (n = 17,522; Figure 1 ). Race/ethnicity was obtained by self-report and was categorized during this study period as singularly white, black, Asian, Hispanic, or other. Institutional review board approval was granted by the Partners Human Research Committee before initiating the study. All study participants provided informed written consent to allow Partners HealthCare to use their health information for Partners Human Research Committee–approved research.

Women were diagnosed with GDM by a 1-hour glucose load test value of ≥7.8 mmol/L (140 mg/dl) and 2 abnormal values on a 3-hour 100-g glucose tolerance test using Carpenter-Coustan criteria. In the event that the participant had multiple pregnancies, we selected the first pregnancy with confirmed GDM to eliminate violations of independence for statistical testing. To examine the implications of eliminating repeated pregnancies, a sensitivity analysis using generalized estimating equations was performed using all pregnancies. Univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazards models predicting hypertension were then repeated, and we found that the hazard ratios differed by <5% and had significantly overlapping confidence intervals (results not shown). Our Cox proportional hazards models did not use a marginal approach, which is normally used for multiple time-to-event analysis in cases when each event is dependent on each other. Of note, the GDM participant may have had pregnancies before or after the selected pregnancy without diagnosed GDM, but this was not considered an exclusion or inclusion criterion for selection. For women without a pregnancy history of GDM and with multiple pregnancies, 1 pregnancy was randomly selected for each mother and they were matched on maternal gravidity to women with GDM in a 4:1 ratio to optimize statistical precision.

The primary outcome, hypertension identified by the ICD-9 Clinical Modification code 401.xx, was obtained from electronic medical records comprising inpatient and outpatient data. Progress notes and other narrative sources of information were not accessed for the purposes of this study. Previous data support the use of ICD-9 Clinical Modification codes for identifying cardiovascular and stroke risk factors with a positive predictive value for hypertension (401.x to 405.x; 437.2) of 0.97 and negative predictive value of 0.52, suggesting that hypertension may be ruled in but may not be ruled out when using only ICD-9 Clinical Modification codes.

Baseline measurements for height, weight, and seated blood pressure were performed and pregnancy history, including gravidity information, was captured at the first prenatal visit for each participant. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight (kilogram)/height (square meter) from the first prenatal visit measurements. Gestational weight gain was calculated as the difference between the initial first-trimester prenatal visit weight and the third-trimester prenatal visit weight measured proximate to delivery. Lipid profiles and smoking history data were abstracted through electronic medical record review of each woman’s encounter with the MGH system within 1 year after delivery. Length of follow-up was calculated from time of delivery to the last visit encounter at MGH.

Characteristics of the study population are described by number (percentage) for categorical variables and mean ± SD of the mean for continuous variables. Independent samples t tests and chi-square tests were used to compare demographic and clinical characteristics by outcome and exposure status. One-way analysis of variance was used to summarize race- and GDM-stratified characteristics. Multiple comparisons were performed as necessary using post hoc adjustments. Follow-up time was summarized using medians. Multivariable Cox proportional hazards models examined the development of hypertension with terms for GDM, age, baseline systolic blood pressure and BMI, parity, race, maternal gestational weight gain, and preeclampsia. Covariates were selected based on statistical significance in age-adjusted analyses. To examine effect modification between GDM and race, race-stratified Cox proportional hazards models were performed. Multivariable race-stratified models retained the same terms as overall models except for race. Women were censored if they developed type 2 diabetes before the development of hypertension to minimize confounding. If no hypertension developed, women were censored at the time of their last MGH encounter. The assumptions of proportional hazards and linearity of continuous covariates were inspected for all final models. A sensitivity analysis was conducted with a total of 5 imputations using the Markov chain Monte Carlo method to account for any differential loss of data for certain minorities. Race, age, parity, systolic blood pressure, weight gain, BMI, and preeclampsia status were used to impute data for all missing values. Sample size calculations were not performed during the study design process. Additionally, as this is a retrospective observational study, no interim analyses were performed. p Values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. The statistical analyses were performed using the SAS for Windows, version 9.2, statistical software package (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, North Carolina).

Results

From the initial population of 23,223 women ( Figure 1 ), 236 (1.0%) had diabetes and 1,126 (4.8%) had CVD before delivery and were excluded from analyses. Baseline characteristics are described in Table 1 . Women with GDM were significantly older, had higher baseline BMI and systolic and diastolic blood pressures, had heavier offspring, had lower gestational weight gain, and were more likely to be of nonwhite race/ethnicity compared with women without GDM. Regarding traditional risk factors for hypertension, we observed no significant difference between women with and without GDM in the frequency of smoking. However, lipid profile analysis revealed that women with GDM had higher triglyceride levels and lower high-density lipoprotein levels compared with those without. Comparing within each racial/ethnic group, women were more likely to have GDM if they were Hispanic or Asian and more likely not to have GDM if they were white or black ( Table 1 ). Notably, regarding hypertension risk factors, Hispanic women were less likely to be past or current smokers compared with white women but had elevated triglyceride levels compared with white, black, and Asian women with GDM ( Table 2 ).