Optimal coronary reflow is the critical key issue to ameliorate clinical outcomes in patients with cardiogenic shock complicating ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (Shock-STEMI). We investigated our hypothesis that pre-percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) procedural coronary thrombectomy may provide clinical advantages to attempt optimal coronary reflow in patients with Shock-STEMI. Of 7,650 patients with acute myocardial infarction registered in the Tokyo CCU Network Scientific Council from January 2009 to December 2011, a total of 180 consecutive patients (144 men, 68 ± 13 years) with Shock-STEMI who showed pre-PCI procedural Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction flow grade 0 (absent initial coronary flow) were recruited. Achievements of post-PCI procedural Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction flow grade 3 (optimal coronary reflow) and also in-hospital mortality were evaluated in those in accordance with and without coronary thrombectomy. Coronary thrombectomy was performed in 128 patients with Shock-STEMI (71% of all). Overall in-hospital mortality was 41% and that in anterior Shock-STEMI with a necessity of mechanical circulatory support increased by 59% (i.e., profound shock). Coronary thrombectomy did not affect any improvements in the achievement of optimal coronary reflow (65% vs 58%, p = 0.368) and in-hospital mortality (42% vs 37%, p = 0.484) in these patients. Even when focused on 76 patients with profound shock, neither an achievement of optimal coronary reflow (56% vs 47%, p = 0.518) nor in-hospital mortality (58% vs 65%, p = 0.601) were different between with and without coronary thrombectomy. Multivariate logistic analysis did not demonstrate any association of coronary thrombectomy (p = 0.798), left main Shock-STEMI (p = 0.258), and use of mechanical circulatory support (p = 0.119) except a concentration of hemoglobin (for each 1 g/dl increase, odds ratio 1.247, 95% confidence interval 1.035 to 1.531, p = 0.019) with optimal coronary reflow. In conclusion, pre-PCI procedural coronary thrombectomy may have serious limitations on attempting optimal coronary reflow that indicates a necessity of promising strategies for this critical illness.

Suboptimal coronary reflow must potentially provide less clinical advantages of percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) in patients with cardiogenic shock complicating ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI). Coronary thrombectomy, which is the removal of coronary thrombus from the infarct-related coronary artery, had been considered as an intuitively attractive strategy to achieve prompt coronary reflow with avoiding a plug of thrombus fragments, thereby salvaging myocardium at risk and so possibly contributing better clinical outcomes in them. In contrast, recent clinical trials demonstrated some limitations of routine coronary thrombectomy that did not reduce short- and long-term mortality compared with conventional PCI in those with STEMI. So far, however, the efficacy of coronary thrombectomy on the highest risk patients, such as those with cardiogenic shock, has remained undetermined in the recent studies. The present study investigated our hypothesis that pre-PCI procedural coronary thrombectomy may provide clinical advantages to attempt optimal coronary reflow and ameliorate clinical outcomes in patients with cardiogenic shock complicating STEMI based on the registry of the Tokyo CCU Network Scientific Council.

Methods

The study population was recruited from the Tokyo CCU Network registered cohort that was operated through 68 hospitals with the help of ambulance units through the control room of the Tokyo Fire Department ( Figure 1 ). Cardiogenic shock was defined in all periods as a systolic blood pressure of <90 mm Hg or the need of high-dose inotrope infusion to maintain a systolic blood pressure >90 mm Hg, clinical signs of respiratory distress with pulmonary congestion, and impaired end-organ perfusion, such as cool extremities, perspiration, and prostration. To evaluate an efficiency of coronary thrombectomy in the setting of abrupt initial coronary flow because of our consideration that the maximal clinical benefits of coronary thrombectomy may be obtained in those with STEMI, a total of 180 consecutive patients (144 men, 68 ± 13 years) with cardiogenic shock complicating STEMI who showed pre-PCI procedural Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) flow grade 0 (absent initial coronary flow) were identified. STEMI was diagnosed according to the established guideline, and PCI procedure such as a type of catheter to aspirate thrombus manually (i.e., coronary thrombectomy), deployment of stent with pre-dilation or directly, and also a use of mechanical circulatory support was at the discretion of a physician in charge. From the hospital records of eligible patients, we abstracted demographic, medical history, and clinical data, and information about emergency medical service, the therapeutic interventions, and laboratory data on hospital admission were evaluated. Post-PCI procedural TIMI flow grade 3 (optimal coronary reflow) and also in-hospital mortality were evaluated in those in accordance with a presence or absence of pre-PCI procedural coronary thrombectomy.

Continuous variables are presented as mean ± SD. Differences in the demographic and clinical characteristics were evaluated using the chi-square tests for categorical variables and a Student’s t test or a Mann-Whitney U test for continuous variables between the 2 groups, in accordance with a presence or absence of coronary thrombectomy with PCI. Cumulative mortality throughout the first 30 days after hospital admission was characterized using Kaplan-Meier curves, with the log-rank test. Multivariate logistic regression models were carried out to assess the independent effect of expected pivotal variables (i.e., coronary thrombectomy, mechanical circulatory support, let main STEMI, and a concentration of hemoglobin) on post-PCI procedural TIMI flow grade 3 in those with anterior STEMI presenting with profound shock. After matching the baseline characteristics of the overall study patients using the propensity score, a prevalence of post-PCI procedural TIMI flow grade 3 was also compared between those with and without coronary thrombectomy. A 2-tailed p value <0.05 denotes a significant difference. The review of patient medical records was approved by the Committee of Tokyo CCU Network Scientific Council.

Results

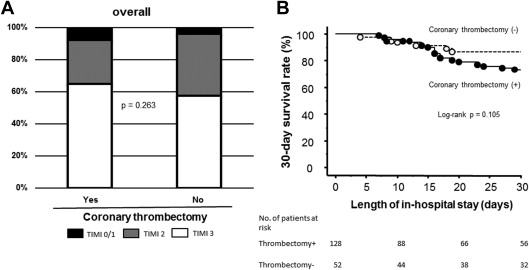

Overall in-hospital mortality was 41%, and 128 patients (71% of all) were treated with coronary thrombectomy ( Table 1 ). Twenty-eight patients (16% of all) were resuscitated from out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. No difference was observed between those with and without coronary thrombectomy as to a proportion of use of stent (93% vs 94%, p = 0.758) and also a proportion of use of bare-metal stents (79% vs 78%, p = 0.936). Compared with those without coronary thrombectomy, pre-PCI procedural coronary thrombectomy did not affect any improvements in the achievement of post-PCI procedural TIMI flow grade 3 and a 30-day survival rate ( Figure 2 ). Finally, in-hospital mortality was 42% with coronary thrombectomy and 37% without (p = 0.484). To address a possible clinical advantage of coronary thrombectomy in a more critical state, namely profound cardiogenic shock, an efficacy of that in a total of 76 patients with anterior cardiogenic shock complicating STEMI with mechanical circulatory support was evaluated ( Table 2 ). In-hospital mortality in those with profound cardiogenic shock increased by 59% (p = 0.006 vs overall). Similar to overall, no difference was found in the achievement of post-PCI procedural TIMI flow grade 3 ( Figure 3 ) and also in-hospital mortality between both the 2 groups (58% vs 65%, p = 0.601). Both the groups demonstrated a similar prevalence of low-output and/or multiorgan dysfunction syndromes as the main cause of in-hospital death (p = 0.615) ( Figure 3 ). Multivariate logistic analysis did not demonstrate any association of coronary thrombectomy with post-PCI procedural TIMI flow grade 3 in those with profound cardiogenic shock complicating anterior STEMI ( Table 3 ). Even after matching baseline characteristics of overall ( Table 4 ), the achievement of post-PCI procedural TIMI flow grade 3 was not different between those with and without coronary thrombectomy (65% vs 59%, p = 0.532).

| Characteristics | PCI with Coronary Thrombectomy | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (N = 128) | No (N = 52) | ||

| Age (years) | 69 ± 13 | 68 ± 13 | 0.666 |

| Men | 103 (80%) | 41 (79%) | 0.805 |

| Body-mass index (kg/m 2 ) | 23 ± 3 | 23 ± 4 | 0.811 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 102 ± 31 | 107 ± 29 | 0.348 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 64 ± 22 | 64 ± 16 | 0.975 |

| Heart rate (beats/min) | 78 ± 32 | 80 ± 25 | 0.698 |

| Creatine kinase on admission (IU/L) | 1313 ± 3093 | 1043 ± 2149 | 0.557 |

| Hypertension | 69 (54%) | 30 (58%) | 0.644 |

| Dyslipidemia | 39 (30%) | 14 (27%) | 0.636 |

| Current smoking | 30 (23%) | 23 (15%) | 0.448 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 35 (27%) | 18 (37%) | 0.332 |

| Previous myocardial infarction | 9 (7%) | 9 (17%) | 0.053 |

| White blood cell counts (/μL) | 12563 ± 10467 | 12883 ± 12237 | 0.876 |

| Hemoglobin (mg/dL) | 13.0 ± 2.7 | 12.9 ± 2.4 | 0.737 |

| Serum creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.64 ± 1.61 | 1.28 ± 1.04 | 0.100 |

| Plasma blood glucose (mg/dL) | 232 ± 105 | 254 ± 112 | 0.277 |

| Onset to hospital arrival time (minutes) | 36 ± 13 | 36 ± 12 | 0.993 |

| Admission on hospital to PCI time (minutes) | 62 ± 57 | 82 ± 77 | 0.237 |

| Anterior acute myocardial infarction | 66 (52%) | 27 (52%) | 0.999 |

| Triple-vessel coronary artery diseases | 17 (13%) | 9 (17%) | 0.486 |

| Mechanical circulatory support device overall | 99 (77%) | 36 (69%) | 0.255 |

| Types of mechanical circulatory support | 0.092 | ||

| Intra-aortic balloon counterpulsation only | 64 (50%) | 20 (39%) | |

| Percutaneous cardio-pulmonary bypass only | 5 (4%) | 1 (2%) | |

| Intra-aortic balloon counterpulsation and percutaneous cardio-pulmonary bypass both | 30 (23%) | 13 (25%) | |

| Ventricular assist device | 0 (0%) | 2 (4%) | |

| Characteristics | PCI with Coronary Thrombectomy | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (N = 59) | No (N = 17) | ||

| Age (years) | 67 ± 14 | 69 ± 16 | 0.557 |

| Men | 50 (85) | 14 (83) | 0.811 |

| Body-mass index (kg/m 2 ) | 23 ± 6 | 25 ± 4 | 0.247 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 98 ± 27 | 108 ± 35 | 0.379 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 66 ± 20 | 64 ± 18 | 0.729 |

| Heart rate (beats/min) | 96 ± 27 | 83 ± 27 | 0.201 |

| Creatine kinase on admission (IU/L) | 2133 ± 4319 | 1600 ± 3284 | 0.634 |

| Hypertension | 30 (51%) | 12 (71%) | 0.149 |

| Dyslipidemia | 20 (34%) | 5 (29%) | 0.729 |

| Current smoking | 13 (22%) | 5 (29%) | 0.852 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 16 (27%) | 5 (29%) | 0.852 |

| Previous myocardial infarction | 3 (5%) | 3 (17%) | 0.091 |

| White blood cell counts (/μL) | 12187 ± 5429 | 9865 ± 3850 | 0.074 |

| Hemoglobin (mg/dL) | 13.5 ± 2.8 | 11.5 ± 2.7 | 0.025 |

| Serum creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.69 ± 1.83 | 1.39 ± 0.72 | 0.355 |

| Plasma blood glucose (mg/dL) | 216 ± 79 | 222 ± 72 | 0.779 |

| Onset to hospital arrival time (minutes) | 35 ± 14 | 36 ± 10 | 0.934 |

| Admission on hospital to PCI time (minutes) | 55 ± 39 | 91 ± 102 | 0.248 |

| Triple-vessel coronary artery diseases | 5 (9%) | 4 (24%) | 0.091 |

| Types of mechanical circulatory support | 0.227 | ||

| Intra-aortic balloon counterpulsation only | 37 (63%) | 8 (47%) | |

| Percutaneous cardio-pulmonary bypass only | 3 (5%) | 1 (6%) | |

| Intra-aortic balloon counterpulsation and percutaneous cardio-pulmonary bypass both | 19 (32%) | 7 (41%) | |

| Ventricular assist device | 0 (0%) | 1 (6%) | |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree