SECTION 1

CLINICAL CASE PRESENTATION

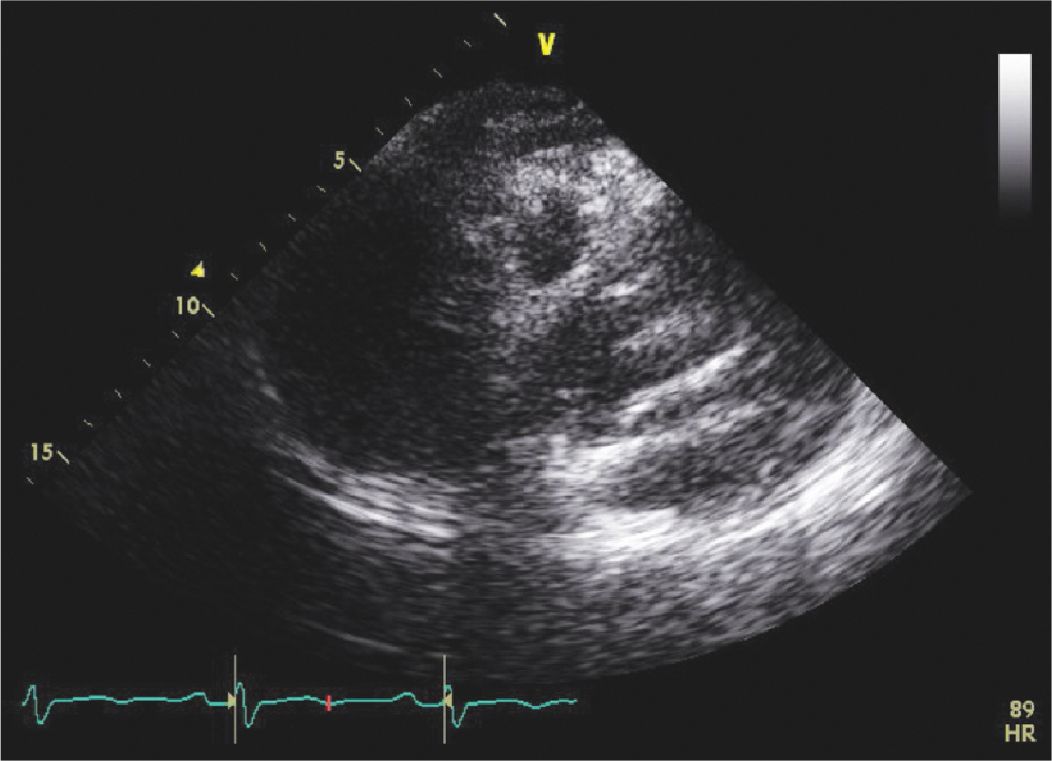

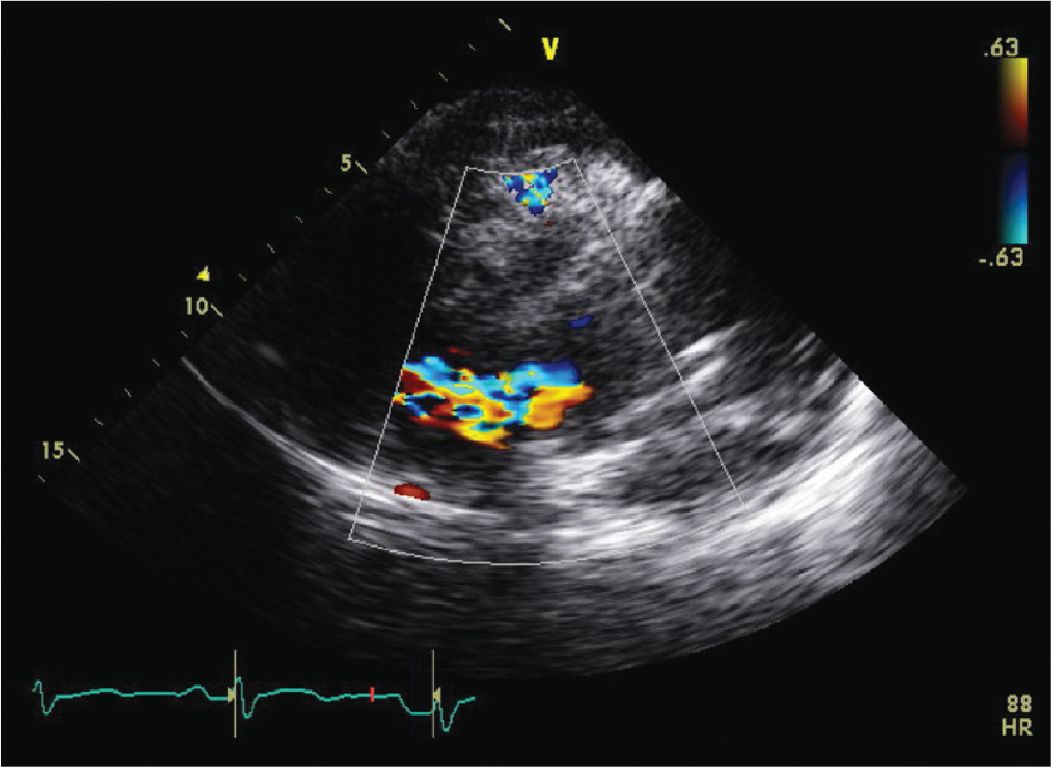

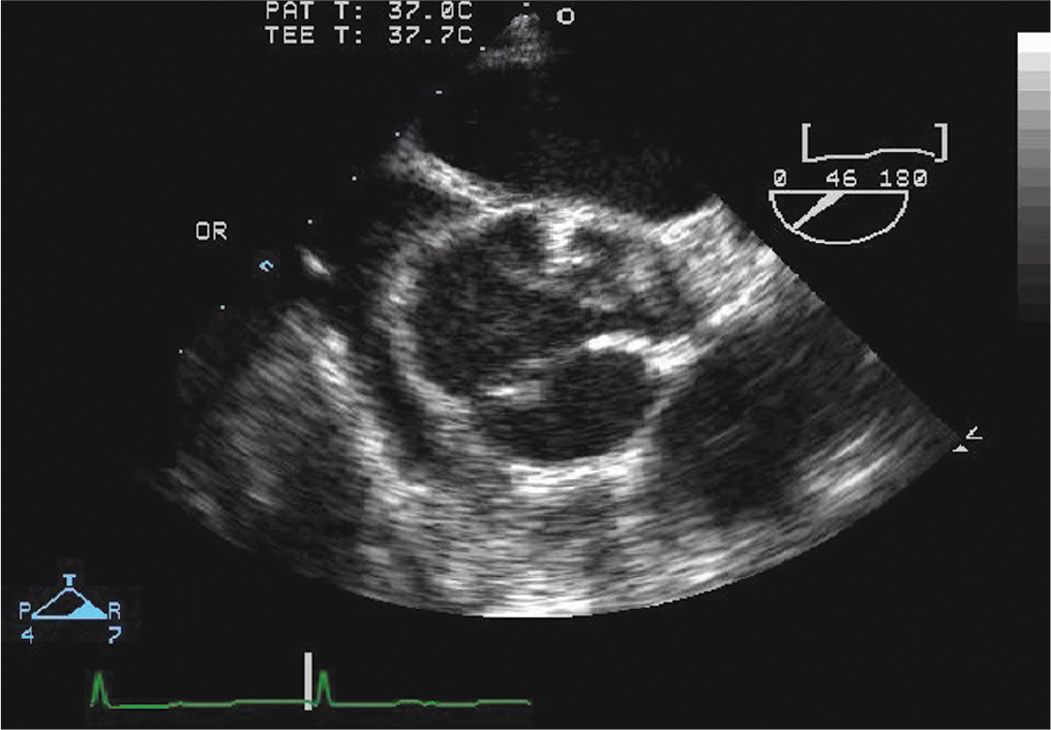

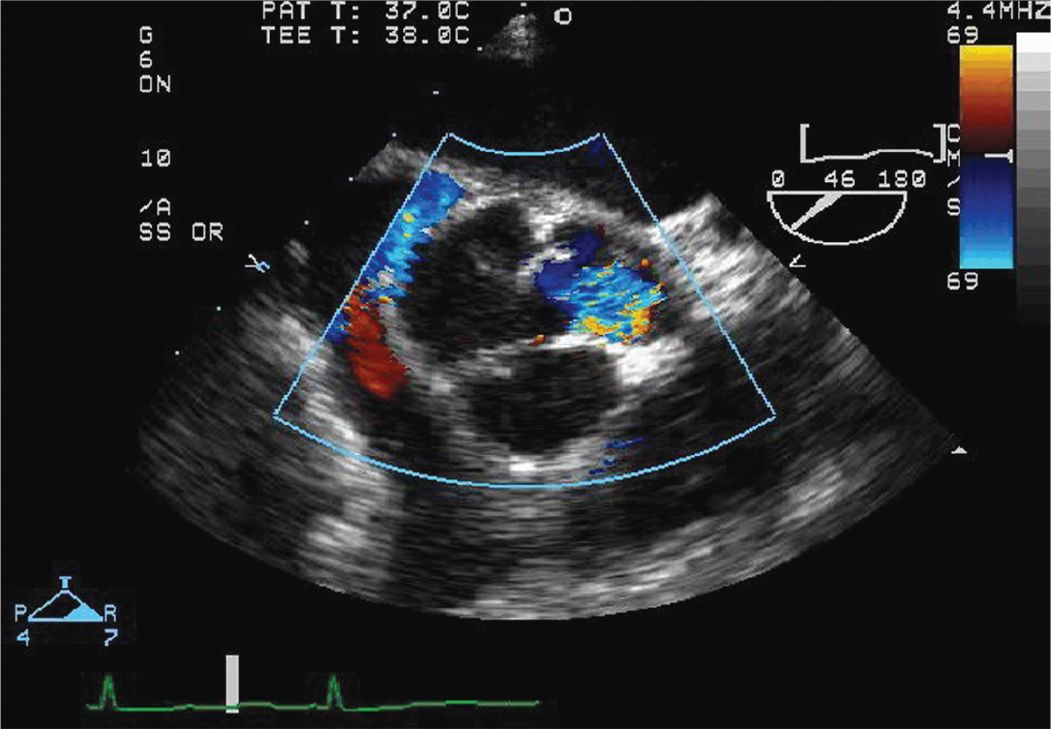

The patient is a 79-year-old woman with a longstanding history of hypertension and a 40 pack-year cigarette smoking history presented to the emergency department with severe chest pain that was described as tearing in nature and was followed by fainting. Her daughter-in-law saw her at the house and called emergency services. On arrival in the emergency department, she was diaphoretic and moaning in pain. An ECG demonstrated normal sinus rhythm with evidence of left ventricular hypertrophy and nonspecific ST-segment changes. On physical examination, her pulses were thready, her blood pressure was 90/30 mm Hg, her apex beat was thrusting, and she had a fourth heart sound with a loud A2. She had a mid-diastolic murmur that was best heard along the sternal border with her leaning forward in expiration. Her lungs were clear and she had no edema. She had a dialysis fistula in her left arm. A transthoracic echocardiogram showed a linear opacity in her ascending aorta and at least moderate aortic regurgitation (Figures 7-1-1 and 7-1-2). After an emergent CT scan confirmed a type A dissection, she was taken to the operating room (OR). Representative intraoperative TEE images are shown in Figures 7-1-3 to 7-1-8. Her dissection was repaired, and the ascending aorta was replaced with a prosthetic graft. She was initially stable following her surgery, but 10 days later she died from surgical complications.

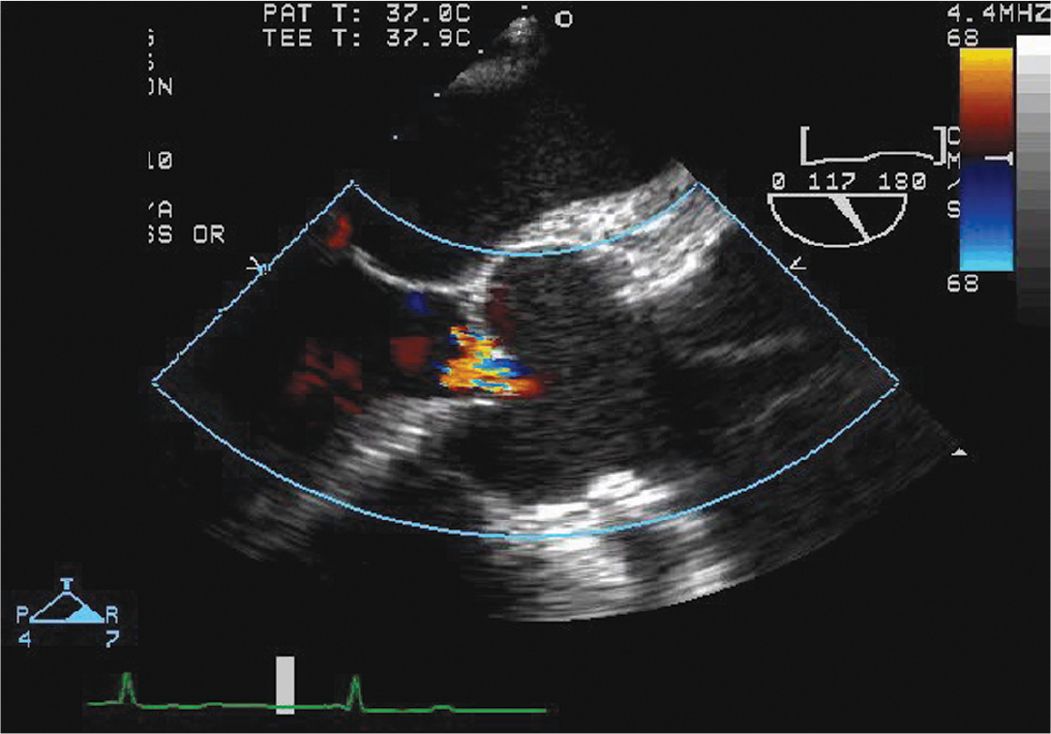

FIGURE 7-1-1 Focused parasternal long axis view. There is a type A dissection with a dissection flap visualized on this TTE.

FIGURE 7-1-2 Parasternal long axis view with color Doppler demonstrating the dissection flap with significant AR due to the aortic dissection.

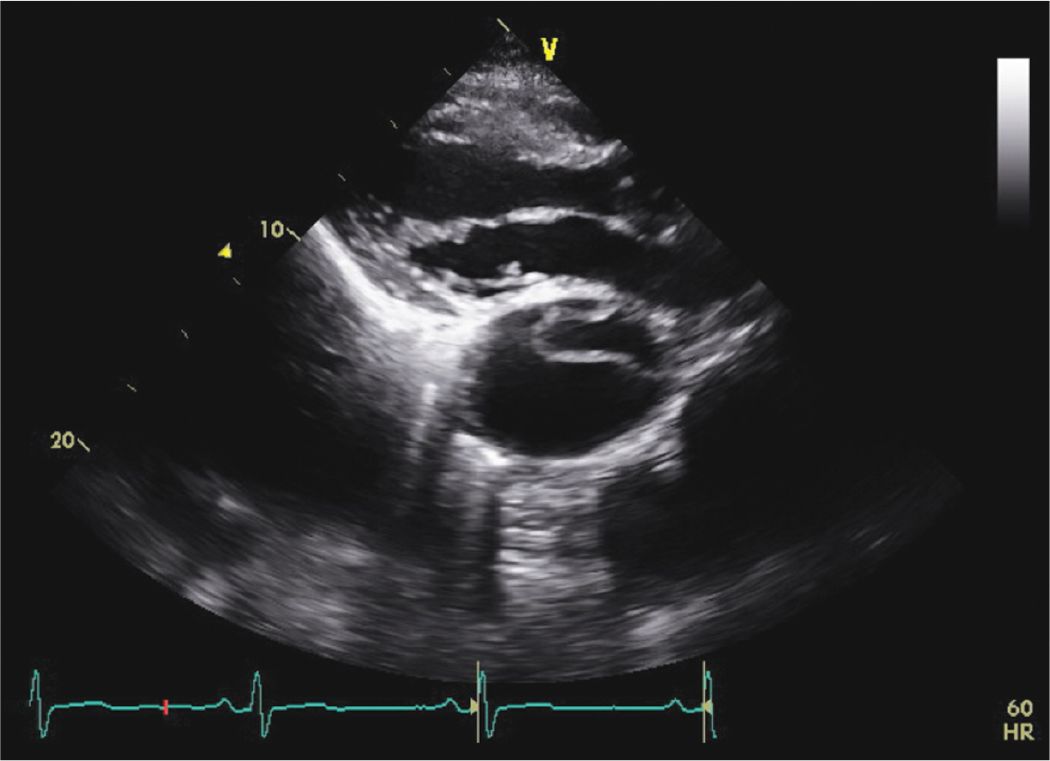

FIGURE 7-1-3 Intraoperative TEE short axis view of the aorta. There is a type A dissection with a large mobile dissection flap. Note the dissection flap prolapsing across the AV, which contributes to the AR.

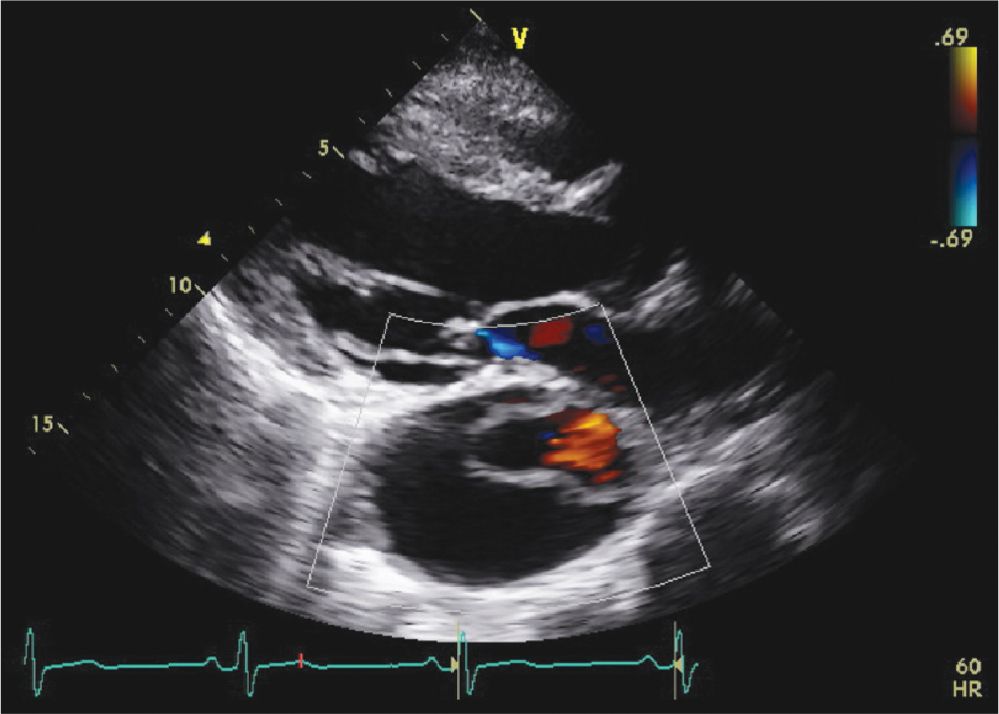

FIGURE 7-1-4 Intraoperative TEE short axis view of the aortic root and aortic valve with color Doppler. There is significant AR caused in part by the dissection flap prolapsing across the AV.

FIGURE 7-1-5 Intraoperative TEE long axis view with color Doppler again demonstrating the dissection flap and associated AR.

FIGURE 7-1-6 Parasternal long axis view demonstrating a dilated descending aorta with a dissection flap in a different patient with a known chronic type B dissection.

FIGURE 7-1-7 Parasternal long axis view from the same patient in Figure 7-1-6 with color flow Doppler demonstrating flow in the true lumen.

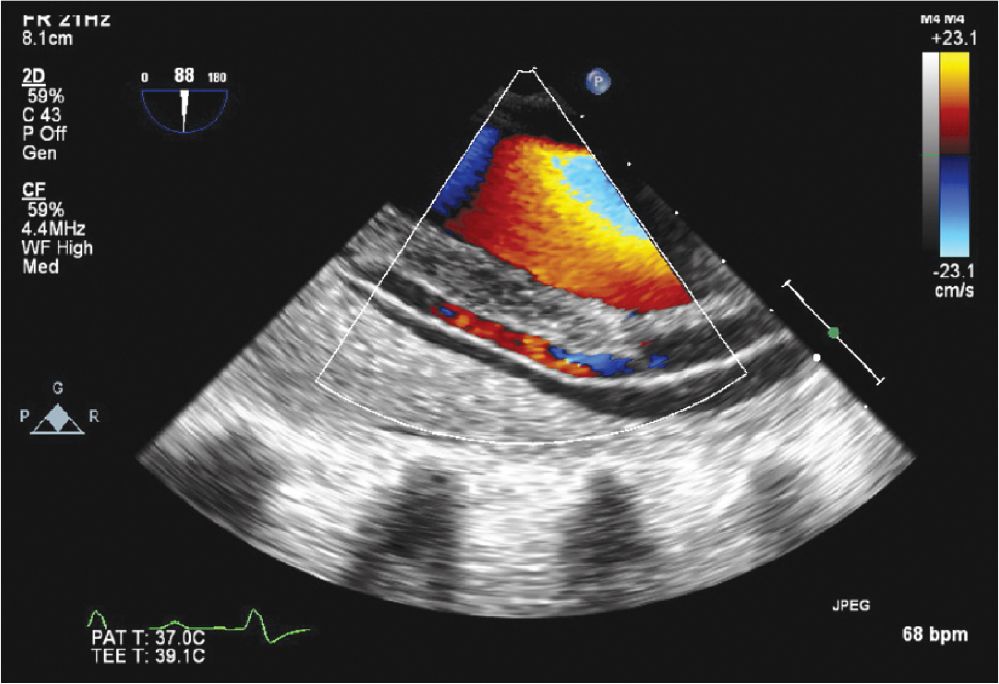

FIGURE 7-1-8 Intraoperative TEE image of another patient with a type A dissection that extended into the descending aorta. There is evidence (color Doppler) of flow in both lumens.

CLINICAL FEATURES AND NATURAL HISTORY

• Patients may present with chest pain. This pain is usually acute, of sudden onset, and severe intensity. However, painless dissection may occur with Marfan syndrome or in patients with neurologic complications.

• The pain may be described as tearing/ripping and radiates to the back or abdomen.

• The site of dissection may be inferred from the location of the pain. Anterior chest pain usually involves the anterior arch or aortic root, interscapular pain usually involves the descending aorta, while neck/jaw pain suggests aortic arch and great vessel involvement.

• Radiation to the neck suggests a type A dissection, while interscapula radiation suggests type B dissection (refer to text below for classification scheme).

• Loss of consciousness may occur.

• There may be a painless interval after the initial episode of pain lasting anywhere from 1 hour to 5 days followed by a return of pain and death.

• Neurologic deficits including symptoms of cerebrovascular accident (CVA), syncope, or altered mental state can occur. Horner’s syndrome can result from interruption of the cervical sympathetic ganglia.

• Dissection into the pleura can manifest with dyspnea and hemoptysis.

• Damage to the kidneys and intestines may occur as a complication of type B dissection and may manifest with hematuria and bowel ischemia.

• Patients may be hypotensive (due to excessive vagal tone, cardiac tamponade, or hypovolemia from aortic rupture) or hypertensive (from catecholamine surge or essential hypertension).

• With type A dissections, clinical signs of aortic regurgitation may be present (bounding pulses, diastolic murmur, increased pulse pressure). Severe aortic regurgitation may present with acute dyspnea.

• Asymmetric pulses and inter-arm systolic blood pressure difference >20 mm Hg may be present.

• Mortality is high.1

EPIDEMIOLOGY

• The incidence of aortic dissection is approximately 2.9 to 3.5 per 100,000 person years.2

• Usually affects persons in their sixth decade of life.

• The most common predisposing features include: hypertension, genetic conditions (Marfan syndrome, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, bicuspid aortic valve, Turner syndrome, Loeys-Dietz syndrome), aortic aneurysm, inflammatory vasculitis (giant cell arteritis, Takayasu arteritis), pregnancy, cocaine abuse, iatrogenic (interventional procedures such as cardiac catherization).

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY AND ETIOLOGY

• The initial lesion is usually a tear in the intima. The resulting column of blood results in dissection of the intimal and medial layers both proximally and distally from the site of the initial tear. Often, several intimal tears are present.

• An intramural hematoma is caused by rupture of the vasa vasorum in the intima and is defined by the absence of an entry point and lack of free flow within the aortic wall. It may, however, progress to a typical dissection if the intima tears.

• Dissections affecting the thoracic aorta may be classified based on the location of the intimal tear or “entry point.” There are two classification schemes (Stanford and Debakey).

![]() Stanford type A includes all dissections involving the ascending aorta, while Stanford type B includes all dissections not involving the ascending aorta.

Stanford type A includes all dissections involving the ascending aorta, while Stanford type B includes all dissections not involving the ascending aorta.

![]() Debakey type I includes all dissections which involve the ascending aorta and extend into the arch; they may extend distally in to the descending aorta. Debakey type II includes all dissections involving and limited to the ascending aorta. Debakey type III includes dissections limited to the descending aorta.

Debakey type I includes all dissections which involve the ascending aorta and extend into the arch; they may extend distally in to the descending aorta. Debakey type II includes all dissections involving and limited to the ascending aorta. Debakey type III includes dissections limited to the descending aorta.

ECHOCARDIOGRAPHY

• Transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) may be useful for detecting ascending aortic dissections, but it has limited ability to visualize the distal ascending aorta and is relatively insensitive compared to other imaging modalities. Complications of a type A dissection (eg, aortic valve incompetence, pericardial effusion, LV dysfunction due to compromise of blood coronary flow) are readily detected by TTE.

• TTE may also demonstrate baseline abnormalities of the aortic valve or root such as aortic stenosis, a bicuspid aortic valve, or dilation of the aortic root, which are predisposing factors for dissection.

• A dissection of the ascending aorta may lead to aortic incompetence in one of 4 ways.

![]() Primary aortic valve abnormality such as a bicuspid aortic valve or preexisting aortic dilation with resultant malcoaptation of the aortic cusps

Primary aortic valve abnormality such as a bicuspid aortic valve or preexisting aortic dilation with resultant malcoaptation of the aortic cusps

![]() Extension of the dissection flap into the sino-tubular junction leading to malcoaptation of an aortic valve cusp

Extension of the dissection flap into the sino-tubular junction leading to malcoaptation of an aortic valve cusp

![]() Extension of the dissection flap into the base of an aortic valve cusp leading to malcoaptation

Extension of the dissection flap into the base of an aortic valve cusp leading to malcoaptation

![]() Extension of the dissection flap in between the aortic valve cusps

Extension of the dissection flap in between the aortic valve cusps

• A dissection flap may be visualized in the proximal ascending aorta.

• The absence of aortic regurgitation and a normal proximal ascending aorta and arch make the presence of an ascending aortic dissection unlikely.

• Transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) is more sensitive than TTE to detect aortic dissection, it can demonstrate the presence and location of an entry point and the extent of the dissection, and it may distinguish both the true and false lumens. Clues to help distinguish between the true and false lumen include:

![]() The lumen into which the aortic valve opens is, by definition, the true lumen.

The lumen into which the aortic valve opens is, by definition, the true lumen.

![]() The true lumen wall is usually round or oval in cross-section.

The true lumen wall is usually round or oval in cross-section.

![]() The true lumen in the descending aorta is usually smaller.

The true lumen in the descending aorta is usually smaller.

![]() The wall of the true lumen is usually pulsatile.

The wall of the true lumen is usually pulsatile.

![]() The presence of swirling echoes or thrombus usually suggests a false lumen.

The presence of swirling echoes or thrombus usually suggests a false lumen.

![]() There may be collagenous strands seen in the false lumen.

There may be collagenous strands seen in the false lumen.

• TEE may also demonstrate the presence of other complications:

![]() Cardiac tamponade due to dissection into the pericardial space

Cardiac tamponade due to dissection into the pericardial space

![]() LV wall motion abnormalities due to extension of the dissection usually into the ostium of the right coronary artery

LV wall motion abnormalities due to extension of the dissection usually into the ostium of the right coronary artery

![]() Extension of the dissection into one of the great vessels of the aortic arch

Extension of the dissection into one of the great vessels of the aortic arch

• Several structures may be confused with a dissection on TEE, including:

![]() The brachiocephalic vein. This may be distinguished from a dissection flap by demonstrating venous flow within the vessel or by injecting agitated saline in to the left arm and demonstrating saline opacification in the vessel.

The brachiocephalic vein. This may be distinguished from a dissection flap by demonstrating venous flow within the vessel or by injecting agitated saline in to the left arm and demonstrating saline opacification in the vessel.

![]() Side lobe artifacts. These may be distinguished from a dissection flap by their relative immobility.

Side lobe artifacts. These may be distinguished from a dissection flap by their relative immobility.

OTHER DIAGNOSIS TESTING AND PROCEDURES

• ECG is recommended for all patients to evaluate for myocardial infarction.3

![]() The absence of ECG abnormalities in a patient with severe chest pain may suggest an aortic dissection.

The absence of ECG abnormalities in a patient with severe chest pain may suggest an aortic dissection.

![]() Since a dissection may extend into a coronary sinus (usually the right) and dissect in to a coronary artery ostium, it may cause an acute myocardial infarction, which can be detected on ECG.

Since a dissection may extend into a coronary sinus (usually the right) and dissect in to a coronary artery ostium, it may cause an acute myocardial infarction, which can be detected on ECG.

• D-dimer may be helpful to exclude a pulmonary embolism.

• The Chest x-ray may demonstrate a widened mediastinum, cardiomegaly (due to a pericardial effusion) or pleural fluid.

• Definitive diagnosis of a thoracic aortic aneurysm/dissection is by transesophageal echocardiography (TEE), CT scan, or MRI.

• TEE has a sensitivity of 100% for detection of a thoracic aortic dissection and 60% for aortic arch vessel involvement, while its specificities were 94% and 85% respectively.4 Its advantages are that it can be deployed quickly in an acute situation and interpreted virtually instantaneously. No radiation or contrast is involved. It can be used irrespective of renal dysfunction, is relatively portable, and may be able to demonstrate the presence of complications.

• Disadvantages of TEE include:

![]() Dependence on superior technical/operator skill.

Dependence on superior technical/operator skill.

![]() Need for conscious sedation and a secure airway.

Need for conscious sedation and a secure airway.

![]() Blind spot that corresponds to the crossing of the bronchus across the distal ascending aorta and proximal arch. However, a dissection that is strictly limited to this area is extremely unlikely.

Blind spot that corresponds to the crossing of the bronchus across the distal ascending aorta and proximal arch. However, a dissection that is strictly limited to this area is extremely unlikely.

![]() Obesity, pulmonary emphysema, and mechanical ventilation can reduce the accuracy of TEE.

Obesity, pulmonary emphysema, and mechanical ventilation can reduce the accuracy of TEE.

• CT scan has a sensitivity of 100% for detection of a thoracic aortic dissection and 93% for an arch vessel involvement with specificities of 100% and 97% respectively.4 Its positive and negative predictive values were 100% and 89% respectively.5 It may help delineate the extent of the dissection all the way to the mesenteric, renal, and iliac arteries. It is also more accurate than TEE or MRI in detecting arch vessel involvement. A significant disadvantage is its inability to show the presence of aortic incompetence and the need for iodinated contrast.

• MRI has a sensitivity of 100% and specificity of 94% for a thoracic aortic dissection and sensitivity of 67% with a specificity of 88% for arch vessel involvement.4 MRI may not be used in patients with metal devices or pacemakers and its use is limited in patients who are claustrophobic. Reports of nephrogenic systemic fibrosis following use of gadolinium in patients with moderate to severe renal insufficiency may limit its use as well. MRI is also limited by its lack of portability.

• The recently published guidelines on management of thoracic aortic disease,3 encourage the use of clinical pretest probability to guide the imaging algorithm for diagnosis.

![]() Three categories of patients are identified based on the aortic dissection diagnosis (ADD) score. Scoring is based on presence or absence of three features:

Three categories of patients are identified based on the aortic dissection diagnosis (ADD) score. Scoring is based on presence or absence of three features:

• High-risk conditions (Marfan syndrome, family history of aortic disease, known aortic valve disease, known thoracic aortic aneurysm, recent aortic manipulation)

• High-risk pain features (abrupt onset, severe, tearing/ripping chest, back or abdominal pain)

• High-risk exam features (pulse deficits, difference in systolic blood pressure, hypotension or shock, new aortic regurgitation murmur, focal neurologic deficit).

![]() Each feature is assigned a score of one (1). This diagnostic algorithm has been shown to be highly sensitive (95% sensitivity) for the diagnosis of acute aortic dissection.6 The specificity is unknown.

Each feature is assigned a score of one (1). This diagnostic algorithm has been shown to be highly sensitive (95% sensitivity) for the diagnosis of acute aortic dissection.6 The specificity is unknown.

![]() The expedited aortic imaging modalities are identified as computed tomography imaging (CT) with angiography, magnetic resonance (MR) imaging with MR angiography (MRA), or TEE with color Doppler flow. In unstable patients, TEE or CT are the imaging modalities of choice.

The expedited aortic imaging modalities are identified as computed tomography imaging (CT) with angiography, magnetic resonance (MR) imaging with MR angiography (MRA), or TEE with color Doppler flow. In unstable patients, TEE or CT are the imaging modalities of choice.

• A chest x-ray is recommended for all patients with low and intermediate risk pretest probability.3 This may demonstrate widening of the mediastinum and unfolding of the aorta. The absence of these features, however, does not rule out a dissection.

• For patients with high pretest probability (ADD score 2-3), immediate surgical consultation and expedited aortic imaging is recommended.3

![]() For patients with intermediate pretest probability (ADD score 1), expedited aortic imaging is recommended if the ECG is not consistent with an ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) and if no alternate diagnosis are suggested by history, physical exam, or chest x-ray.3

For patients with intermediate pretest probability (ADD score 1), expedited aortic imaging is recommended if the ECG is not consistent with an ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) and if no alternate diagnosis are suggested by history, physical exam, or chest x-ray.3

![]() For a low pretest probability (ADD score 0), recommendation is to proceed with diagnostic evaluation as indicated by the clinical presentation. If no alternate diagnosis is identified and there is widened mediastinum on CXR or unexplained hypotension, the recommendation is to proceed with expedited aortic imaging.3

For a low pretest probability (ADD score 0), recommendation is to proceed with diagnostic evaluation as indicated by the clinical presentation. If no alternate diagnosis is identified and there is widened mediastinum on CXR or unexplained hypotension, the recommendation is to proceed with expedited aortic imaging.3

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

• Acute myocardial infarction

• Pulmonary embolism

• Spontaneous pneumothorax

• Acute pericarditis

• Mesenteric ischemia

DIAGNOSIS

• The diagnosis of an aortic dissection is made by demonstrating an intimal flap with any of the above imaging modalities, which can also demonstrate complications of the dissection and help to guide management.

MANAGEMENT

• Definitive treatment of a type A aortic dissection is surgical. Dissections involving the descending aorta (type B) are treated medically unless there is intractable pain, uncontrolled hypertension, extension of the dissection, or end organ damage (limb or visceral ischemia).

• Medical management (acutely prior to surgery for a type A dissection and for all type B dissections) includes:

![]() Pain control with opiates may help with blood pressure management.

Pain control with opiates may help with blood pressure management.

![]() β-Blockers can reduce the heart rate and blood pressure and therefore minimize hemodynamic shear stress on the aorta. Target blood pressure is <120 mm Hg systolic, and a target heart rate is <60 beats per minute. Calcium channel blockers may be used for persons intolerant of β-blockers.

β-Blockers can reduce the heart rate and blood pressure and therefore minimize hemodynamic shear stress on the aorta. Target blood pressure is <120 mm Hg systolic, and a target heart rate is <60 beats per minute. Calcium channel blockers may be used for persons intolerant of β-blockers.

![]() If the blood pressure remains elevated, then a vasodilator such as nitroprusside may be added in addition to a β-blocker.

If the blood pressure remains elevated, then a vasodilator such as nitroprusside may be added in addition to a β-blocker.

FOLLOW-UP

• Lifelong blood pressure (BP) control is required post discharge. Goal BP is <120/80 mm Hg.

• Regular imaging is also required at 1, 3, 6 and 12 months after the initial event, looking for signs of aortic expansion, aneurysm formation, malperfusion and leakage at anastomotic sites. Thereafter, yearly imaging is recommended. CT or MRI is usually employed for follow-up imaging.

• Patient education regarding the signs and symptoms of recurrent dissection or potential postdissection complications is also recommended.

REFERENCES

1. Miller DC, Mitchell RS, Oyer PE, Stinson EB, Jamieson SW, Shumway NE. Independent determinants of operative mortality for patients with aortic dissections. Circulation. 1984;70(3 Pt 2): I153-164.

2. Clouse WD, Hallett JW Jr, Schaff HV, et al. Acute aortic dissection: population-based incidence compared with degenerative aortic aneurysm rupture. Mayo Clin Proc. Feb 2004;79(2):176-180.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree