SECTION 1

CLINICAL CASE PRESENTATION

The patient is a young man who was recently diagnosed with stage IV non-small cell lung carcinoma. He also has a history of COPD. He presented to the emergency room with worsening dyspnea for approximately 2 weeks. He had been treated with inhalers without improvement in his symptoms. He also noted increasing cervical adenopathy and generalized upper and lower extremity swelling. He had initially presented (3 months prior to this presentation) with dyspnea, and further workup demonstrated a left upper lobe mass as well as significant mediastinal adenopathy. He was treated with radiation therapy with plans for further chemotherapy, which had not been started.

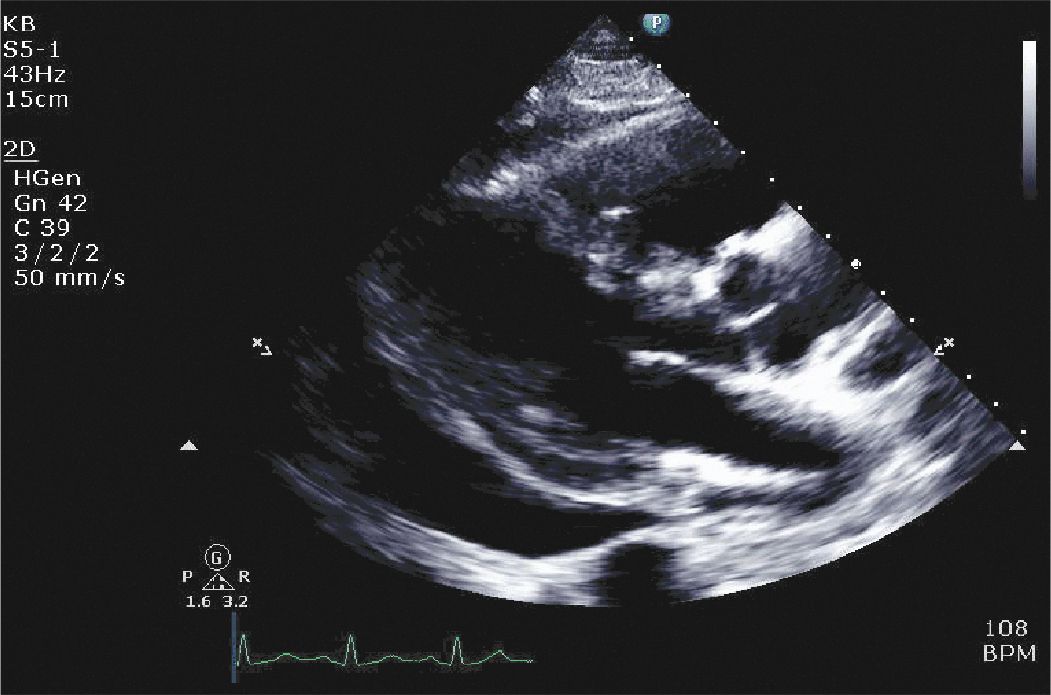

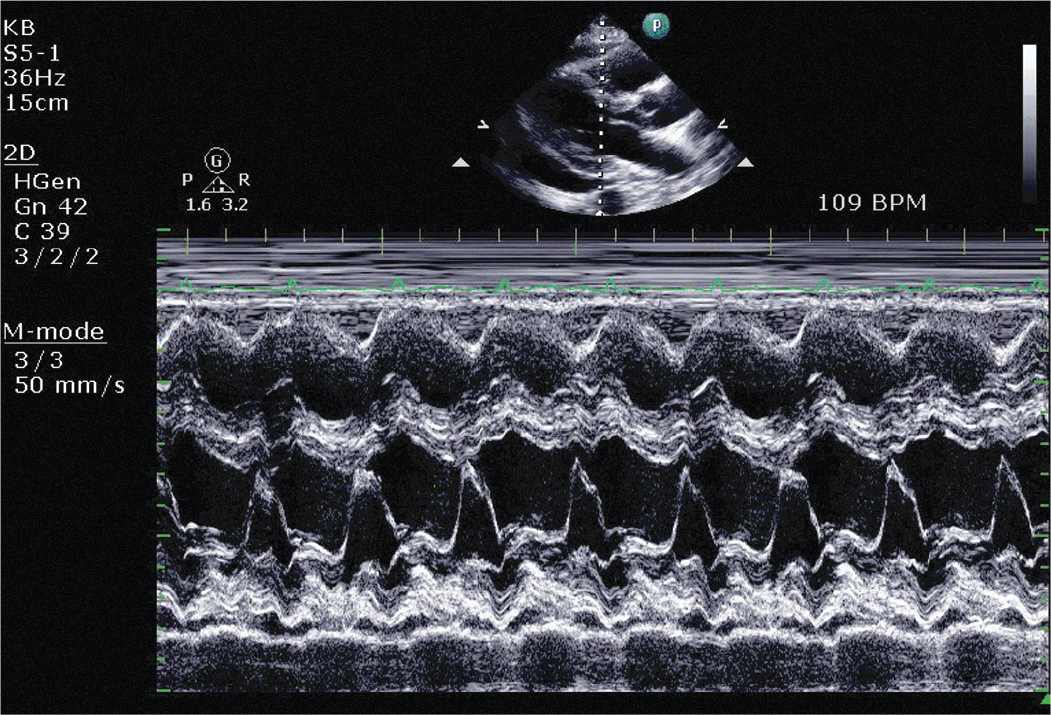

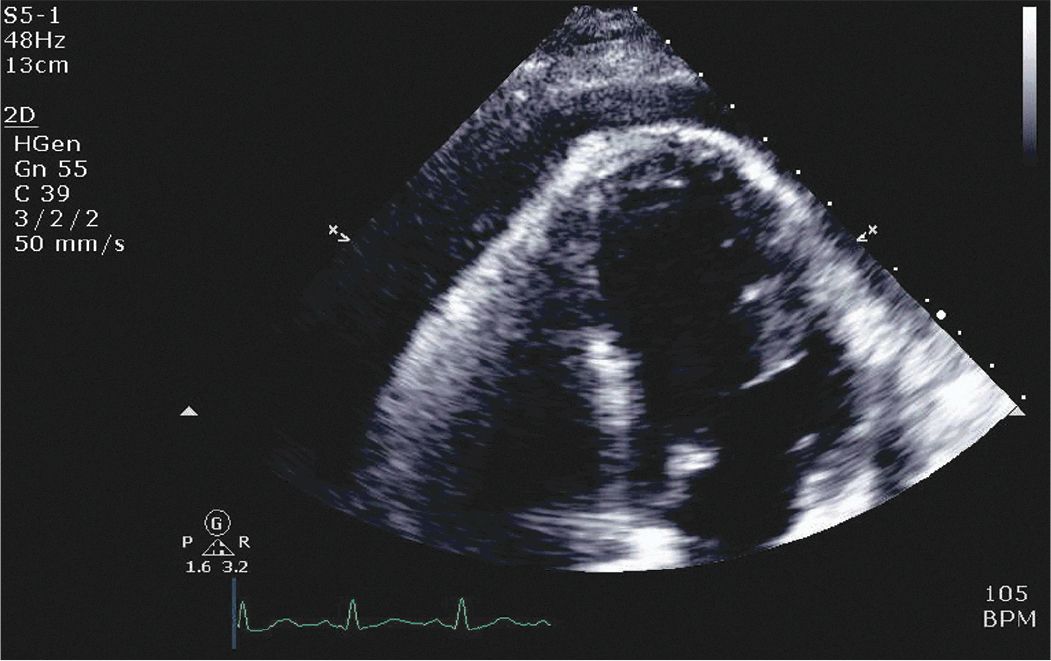

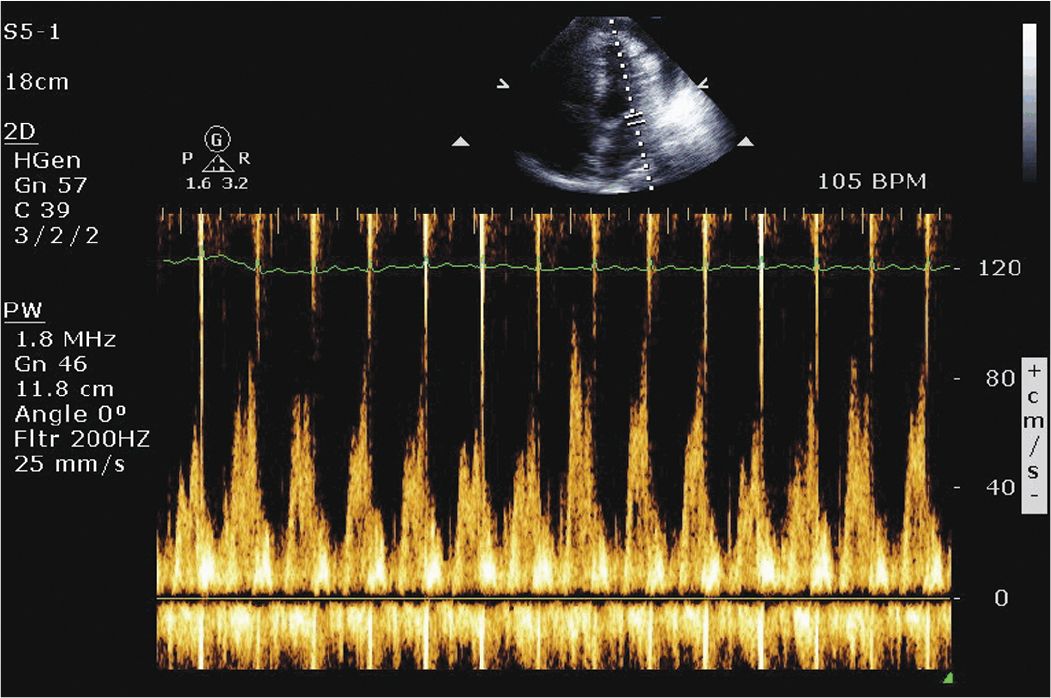

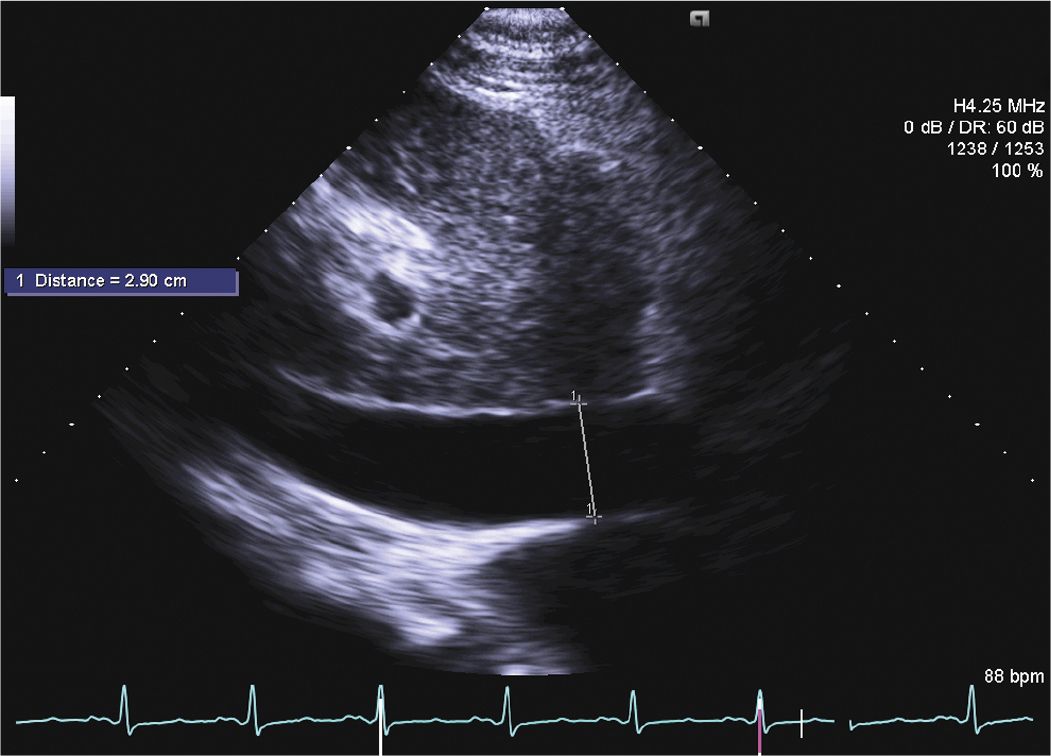

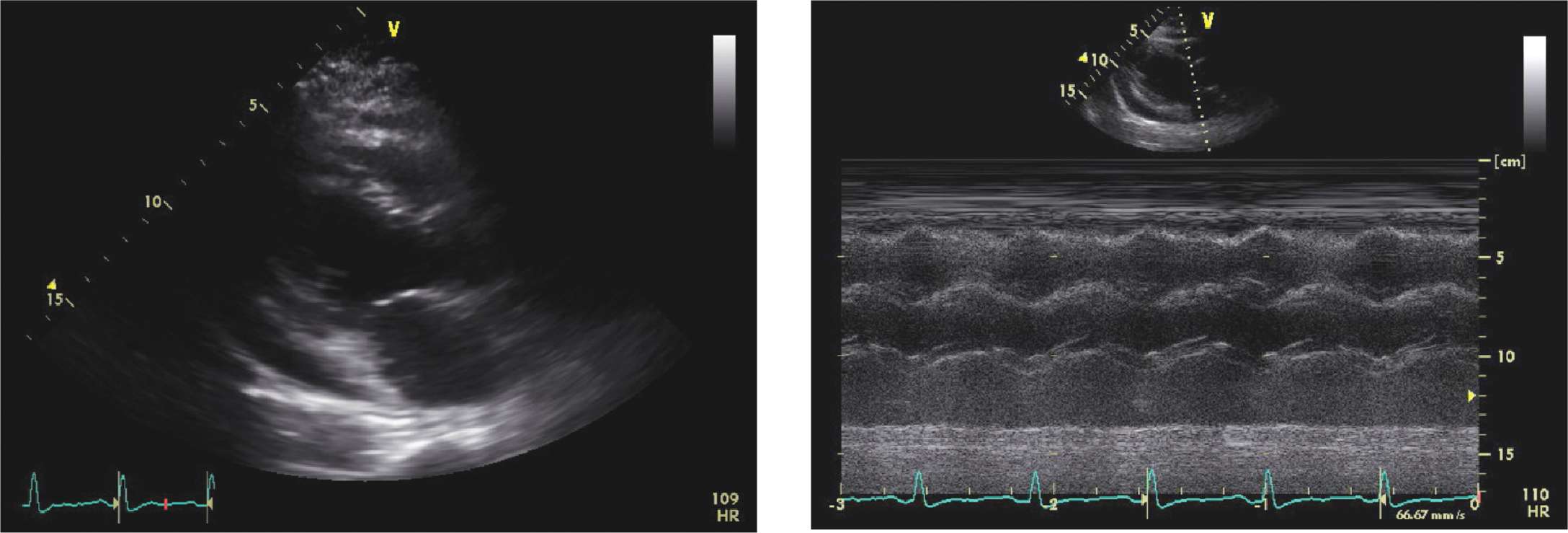

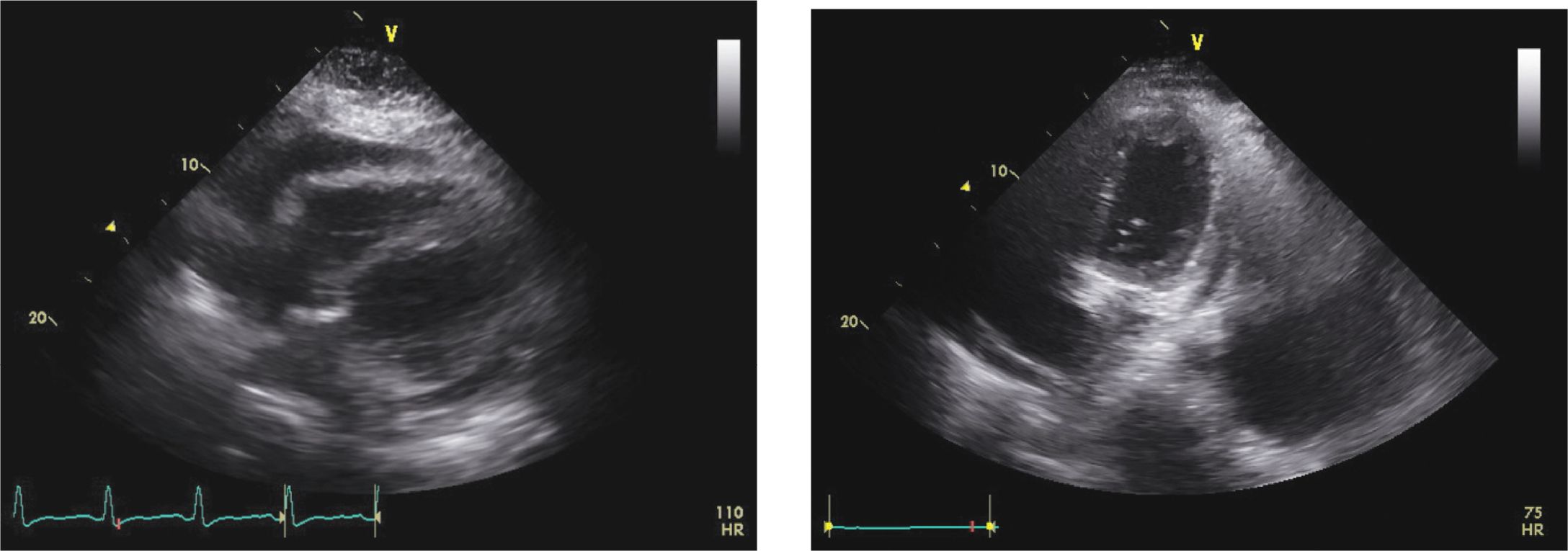

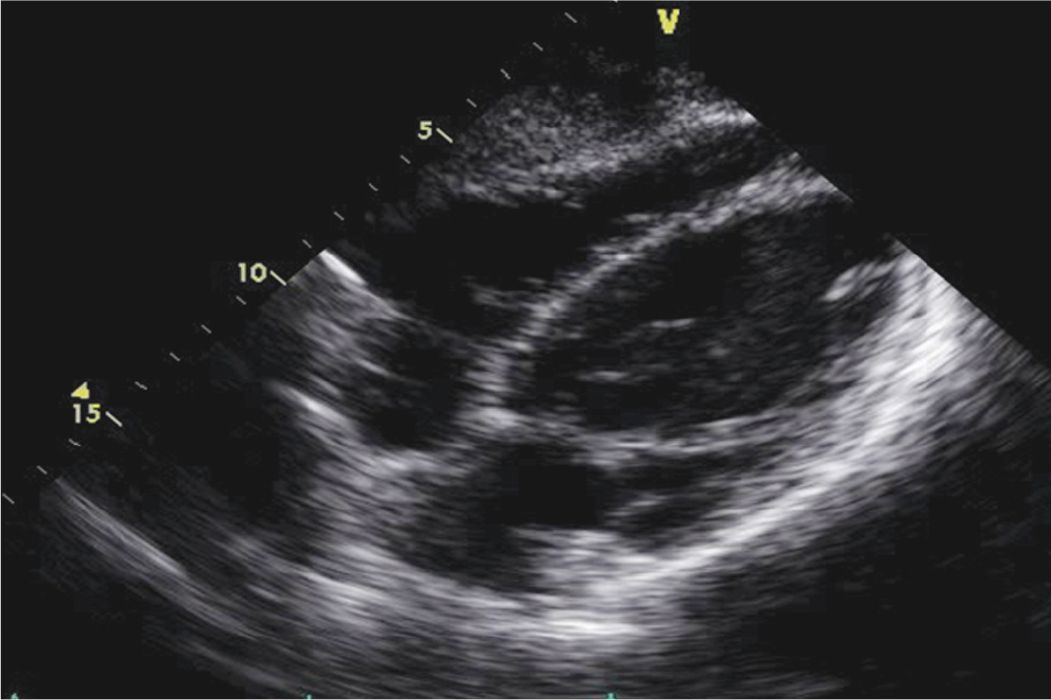

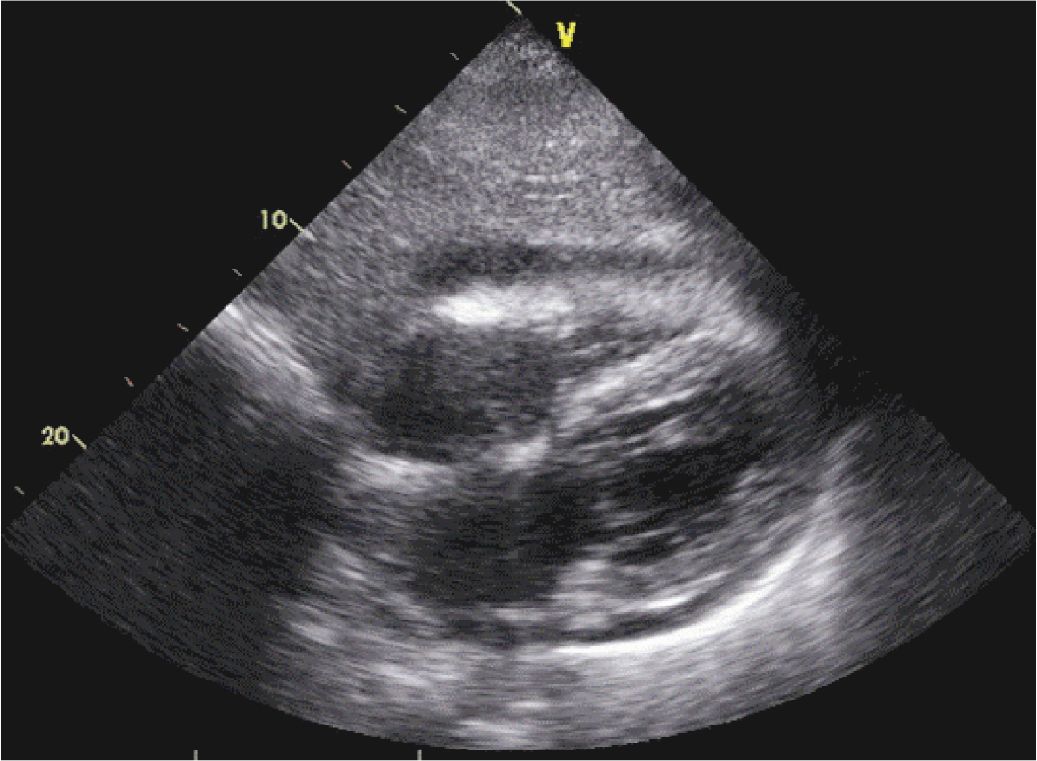

On physical examination he was found to be tachycardic. He did not have significant neck vein distention. Cardiac exam revealed that he was tachycardiac with no murmurs, gallops, or rubs. He had trace lower extremity edema. Given his physical exam findings and hypoxia there was concern that he could have a pulmonary embolism, and therefore a CT pulmonary embolism study was performed. This demonstrated no evidence of pulmonary embolism but did demonstrate a pericardial effusion. A transthoracic echocardiogram was requested. The echocardiogram demonstrated a large pericardial effusion with evidence of tamponade (Figures 6-1-1 to 6-1-5).

FIGURE 6-1-1 Parasternal long axis demonstrating a large pericardial effusion with evidence of right ventricular collapse.

FIGURE 6-1-2 Two-dimensional guided M-mode demonstrating RV diastolic collapse.

FIGURE 6-1-3 Apical 4 chamber view demonstrating a large pericardial effusion with visceral pericardial thickening and right atrial collapse.

FIGURE 6-1-4 Pulse wave Doppler demonstrating respiratory variation of mitral inflow, a sign of cardiac tamponade.

FIGURE 6-1-5 Subcostal view demonstrating a dilated inferior vena cava.

The patient underwent open drainage with creation of a pericardial window. Pathology did not reveal any tumor. A subsequent chest CT demonstrated no pericardial fluid. He was subsequently discharged with plans for institution of outpatient chemotherapy.

CLINICAL FEATURES AND NATURAL HISTORY

• Patients with pericardial involvement due to a malignancy may present with an asymptomatic effusion (detected during imaging for other reasons) or may present with symptoms of pericarditis such as chest pain, cardiac tamponade, or pericardial constriction.

• Signs and symptoms may include chest pain, dyspnea, tachycardia, hypotension, and edema.

• Once any acute hemodynamic issues related to pericardial involvement are addressed, such as treatment of cardiac tamponade (Figures 6-1-6 and 6-1-7), the natural history and prognosis are usually driven by the underlying malignancy. Pericardial involvement usually portends a poor prognosis.5

FIGURE 6-1-6 Moderate-sized pericardial effusion in a different patient with RV collapse (left). The M-mode demonstrates RV diastolic collapse (right).

FIGURE 6-1-7 Pre- (left) and post- (right) echocardiogram from the patient in Figure 6-1-6 demonstrating resolution of the pericardial effusion post-pericardiocentesis.

EPIDEMIOLOGY6,7

• Pericardial involvement due to malignancy is not uncommon, occurring in up to 20% of patients depending on the malignancy.6

• The differential diagnosis of pericardial effusions is extensive. Several etiologies are explored in more detail in other sections of this chapter.

• The etiology of a large pericardial effusion will vary depending on the patient population studied. Obvious causes may be determined by history (eg, chest trauma, post cardiac surgery, post myocardial infarction, or post cardiac procedure). In a large cancer centers, malignancies may predominate. Case series report varying etiologies. In one series of 322 patients,7 in which 37% of the patients had cardiac tamponade, the etiology of the effusion was as follows: idiopathic, 20%; iatrogenic, 16%; malignancy, 13%; chronic idiopathic effusion, 9%; post myocardial infarction, 8%; uremia, 6%; collagen vascular disease, 5%; infection, 6%; hypothyroidism, 2%; miscellaneous, 15%.

• Table 6-1-1 provides broad categories in the differential diagnosis of pericardial effusion. This is certainly not an exhaustive list, but it references the more common etiologies in each category.8

• In patients without a known underlying malignancy, pericardial disease as the first manifestation of cancer is uncommon. This is especially true if the effusion is small. In one series of patients with acute pericarditis or small effusions, 5% were ultimately diagnosed with a malignancy.9

• In the population of patients presenting with large effusions or cardiac tamponade and in whom the etiology is not evident after a basic evaluation, malignancy is not an uncommon etiology. Nearly 20% of such patients in one series were found to have an underlying malignancy.10

TABLE 6-1-1 Differential Diagnosis of Pericardial Effusion

• Idiopathic

• Viral

![]() Multiple organisms, including HIV, cocsackie, influenza

Multiple organisms, including HIV, cocsackie, influenza

• Malignant

• Metabolic (eg, uremic, dialysis-related, hypothyroidism)

• Bacterial (purulent) pericarditis

• Tuberculous pericarditis

• Other infections (eg, fungal, parasitic)

• Connective tissue diseases/vasculitis

![]() eg, systemic lupus, rheumatoid arthritis, scleroderma

eg, systemic lupus, rheumatoid arthritis, scleroderma

• Mediastinal radiation

• Postcardiac surgery

• Cardiac injury as a complication of cardiac procedures

• Postmyocardial infarction

• Aortic dissection

• Chest trauma (blunt/penetrating)

• Drugs/toxins

Adapted with permisison from Spodick, DH. Pericardial Diseases. In: Heart Disease: A Textbook of Cardiovascular Medicine, Braunwald E, Zipes D, Libby P (Eds). New York, NY: Saunders; 2001. Page 1823.8

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY AND ETIOLOGY OF MALIGNANT PERICARDIAL EFFUSIONS

• The pathophysiology of pericardial involvement in malignancy may be due to direct extension into the pericardium (eg, lung cancer, esophageal cancer).

• Alternatively, metastatic spread to the pericardium via the hematogenous route or the lymphatic system may occur. Primary pericardial malignancy is quite rare.

• Among the various primary malignancies, lung, breast and esophageal cancers, malignant melanoma as well as leukemias and lymphomas most commonly affect the pericardium5,11 (Table 6-1-2).

• Cardiac tamponade, as was seen in this case, results from extrinsic compression of the heart as fluid accumulates in the semi-rigid pericardium. Once intrapericardial pressure exceeds the intracardiac pressure, cardiac filling is limited, and the patient may develop hypotension and tachycardia. On physical examination, the neck veins may be elevated with prominent x descents, and a pulsus paradoxus may be appreciated.

TABLE 6-1-2 Common Malignancies with Pericardial Involvement

• Lung

• Breast

• Esophageal

• Melanoma

• Lymphoma

• Leukemia

• Mesothelioma

ECHOCARDIOGRAPHY12

• Echocardiography is the diagnostic test of choice to assess for the presence, size, and physiologic consequences of pericardial effusion.

• Pericardial fluid appears as an echo free space between the parietal and visceral pericardium. Small effusions are usually seen posterior to the heart, frequently in the atrioventricular groove. As the size of the effusion increases, fluid can be seen around the left and right ventricles, around the right atrium and posterior to the left atrium.

• Echocardiographic features of cardiac tamponade reflect the increase in intrapericardial pressure as compared to the intracardiac pressure (chamber collapse), elevated intracardiac pressure (IVC findings), and the effects of respiration (mitral and tricuspid filling patterns, caval flow).

• A variety of echocardiographic features support the diagnosis of pericardial tamponade.

![]() Right atrial inversion/collapse can be seen with both 2-dimensional and M-mode imaging. M-mode provides better temporal resolution and can be helpful in timing events as they relate to the cardiac cycle.

Right atrial inversion/collapse can be seen with both 2-dimensional and M-mode imaging. M-mode provides better temporal resolution and can be helpful in timing events as they relate to the cardiac cycle.

![]() Right ventricular collapse: Typically seen in the RVOT, the free wall of the RV may also be compressed and demonstrate chamber collapse in diastole.

Right ventricular collapse: Typically seen in the RVOT, the free wall of the RV may also be compressed and demonstrate chamber collapse in diastole.

![]() Since RA pressure is lower than RV pressure, RA collapse tends to occur earlier (more sensitive) in the spectrum of tamponade than RV collapse. RV collapse is a more specific sign of tamponade.

Since RA pressure is lower than RV pressure, RA collapse tends to occur earlier (more sensitive) in the spectrum of tamponade than RV collapse. RV collapse is a more specific sign of tamponade.

![]() Respiratory variation of mitral and tricuspid inflow.

Respiratory variation of mitral and tricuspid inflow.

![]() IVC plethora.

IVC plethora.

OTHER DIAGNOSTIC TESTING AND PROCEDURES

• Echocardiography is the principal imaging modality for the diagnosis and follow-up of pericardial effusions.

• The chest x-ray may demonstrate cardiomegally.

• With a large effusion, the ECG voltage may be low, and electrical alternans may be present.

• Both chest computed tomography CT and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may detect pericardial fluid incidentally (as was the case on our patient). Cardiac CT and MRI may be useful in further evaluating the pericardial anatomy/thickness and assessing contiguous structures in the chest.

• In patients with equivocal findings for tamponade and to help in the diagnostic assessment of the hemodynamic consequences of an effusion, cardiac catheterization with hemodynamic assessment may be warranted.

• Basic laboratory investigation to assess for other potential etiologies would include renal function, thyroid function, a complete blood count, and selected markers for connective tissue disease.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

• As has been explored in this section, the differential diagnosis of a pericardial effusion is quite broad.

• In a patient with a known malignancy, especially a malignancy with a predilection for cardiac involvement, malignancy must be entertained. If the patient has undergone chest radiation with the heart/pericardium in the radiation field, radiation-induced pericardial involvement is possible. Some chemotherapeutic agents may also cause pericardial effusions. In immunocompromised subjects, an infectious etiology must be considered.

• Etiologies of pericardial effusion not related to the malignancy or its treatment must also be considered. A careful history is imperative to explore other systemic signs/symptoms that may lead to an alternative diagnosis.

DIAGNOSIS

• Diagnosing the presence and extent of pericardial effusion is usually straightforward.

• In many cases, the hemodynamic/clinical impact of the effusion may be difficult to ascertain. Patients with malignancy may have other causes for their symptoms. For example, a patient with lung cancer and dyspnea may be short of breath due to the malignancy, concomitant COPD, pneumonia, etc. Infections and other clinical factors such as volume depletion may be the etiology of tachycardia and hypotension, rather than the effusion.

• Diagnosing a malignant effusion can be difficult. Standard fluid analysis (cell count, glucose, protein, and lactate dehydrogenase) should be performed. The diagnostic yield of cytology of the pericardial fluid is frequently unrewarding. Reported sensitivities for the diagnostic yield of cytology vary from 51% to 92%.10,13

• A pericardial biopsy may be needed to make the diagnosis.

MANAGEMENT

• The management of malignant pericardial effusions is somewhat controversial. Patients with hemodynamic compromise require removal of the fluid. In many cases, this must be performed emergently to prevent hemodynamic collapse. This is best accomplished with percutaneous drainage, often with echocardiographic guidance.

• In less urgent situations, several options exist. Some experts advocate open pericardial drainage, as was performed in this case, with or without pericardiectomy or the creation of a pericardial window. Others advocate simple percutaneous pericardiocentesis to remove the fluid or percutaneous pericardial drainage with prolonged catheter drainage.14

• Malignant effusions not infrequently reaccumulate, depending on the initial therapeutic approach, the underlying malignancy, and its response to therapy. Simple pericardiocentesis may result in fluid reaccumulation within 48 hours. Extended catheter drainage appears to be more effective in preventing recurrence (12%) compared to simple drainage (36%). Surgical management is more effective (0%), albeit with more potential morbidity/mortality.14

FOLLOW-UP

• Following therapy (either open drainage or percutaneous drainage), documentation of improvement/resolution of the effusion, usually with a repeat echocardiogram, is appropriate.

• Patients with a malignant pericardial effusion require ongoing follow-up with oncology for their underlying malignancy and its response to therapy.

• Pericardial involvement usually portends a poor prognosis, and the presence of malignant cells in the fluid worsens the prognosis. In one series, patients with a malignancy associated effusion on average survived 15.1 weeks. Those with positive cytology had a median survival of 7.3 weeks, compared to 29.7 weeks in patients without a positive cytology.5

• If recurrent signs or symptoms of cardiac/pericardial involvement develop, repeat echocardiography to assess for the recurrence of the effusion or the development of constrictive physiology is warranted.

REFERENCES

1. Feigenbaum H, Waldhausen JA, Hyde LP. Ultrasound diagnosis of pericardial effusion. JAMA. 1965;191:711-714.

2. Cheitlin MD, Armstrong WF, Aurigemma GP, et al. ACC/AHA/ASE 2003 guideline update for the clinical application of echocardiography- summary article A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines. (ACC/AHA/ASE 2003 Committee to Update the 1997 Guidelines for the Clinical Application of Echocardiography). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;42:954-970.

3. Douglas PS, Garcia MJ, Haines DE, et al. ACCF/ASE/AHA/ASNC/HFSA/HRS/SCAI/SCCM/SCCT/SCMR 2011 appropriate use criteria for echocardiography: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Appropriate Use Criteria Task Force, American Society of Echocardiography, American Heart Association, American Society of Nuclear Cardiology, Heart Failure Society of America, Heart Rhythm Society, Society of Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society of Critical Care Medicine, Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography, and Society of Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57(9):1126-1166. doi: 10.1016/jacc.2010.11.002.

4. Klein AL, Abbara S, Agler DA, et al. American Society of Echocardiography clinical recommendations for multimodality cardiovascular imaging of patients with pericardial disease: endorsed by the Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance and Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2013;26:965-1012.

5. Gornik HL, Gerhard-Herman M, Beckman JA. Abnormal cytology predicts poor prognosis in cancer patients with pericardial effusion. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:5211-5216.

6. Maisch B, Ristic A, Pankuweit S. Evaluation and management of pericardial effusion in patients with neoplastic disease. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2010;53:157-163.

7. Sangrista-Saluda J, Merce J, Parmanyer-Miralda G, Soler-Soler J. Clinical clues to the causes of large pericardial effusions. Am J Med. 2000;109:95-101.

8. Spodick, DH. Pericardial Diseases. In: Braunwald E, Zipes D, Libby P, eds. Heart Disease: A Textbook of Cardiovascular Medicine. New York, NY: Saunders; 2001:1823-1876.

9. Imazio M, Cecchi E, Demichelis B, et al. Indicators of poor prognosis of acute pericarditis. Circulation. 2007;115: 2739-2744.

10. Ben-Horin S, Bank I, Guetta V, Livneh A. Large symptomatic pericardial effusion as the presentation of unrecognized cancer: a study in 173 consecutive patients undergoing pericardiocentesis. Medicine. 2006;85:49-53.

11. Abraham KP, Reddy V, Gattuso P. Neoplasms metastatic to the heart: review of 3314 consecutive autopsies. Am J Cardiovasc Pathol. 1990;3:195-198.

12. Wann S, Passen E. Echocardiography in pericardial disease. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2008;21:7-13.

13. Meyers DG, Meyers RE, Prendergast TW. The usefulness of diagnostic tests on pericardial fluid. Chest. 1997;111:1213-1221.

14. Tsang TSM, Seward JB, Barnes ME, et al. Outcomes of primary and secondary treatment of pericardial effusion in patients with malignancy. Mayo Clin Proc. 2000;75:248-253.

SECTION 2

CLINICAL CASE PRESENTATION

A 33-year-old man presents to the emergency department after the subacute onset of a sharp, substernal chest pain. This pain developed over the course of 2 to 3 hours. The pain is worse when he is laying flat and when he takes a deep breath. The pain improves when he is sitting upright. He has no significant past medical history, has had no prior surgeries, and takes no regularly scheduled medications. He is a lifelong nonsmoker and has no family history of cardiac disease.

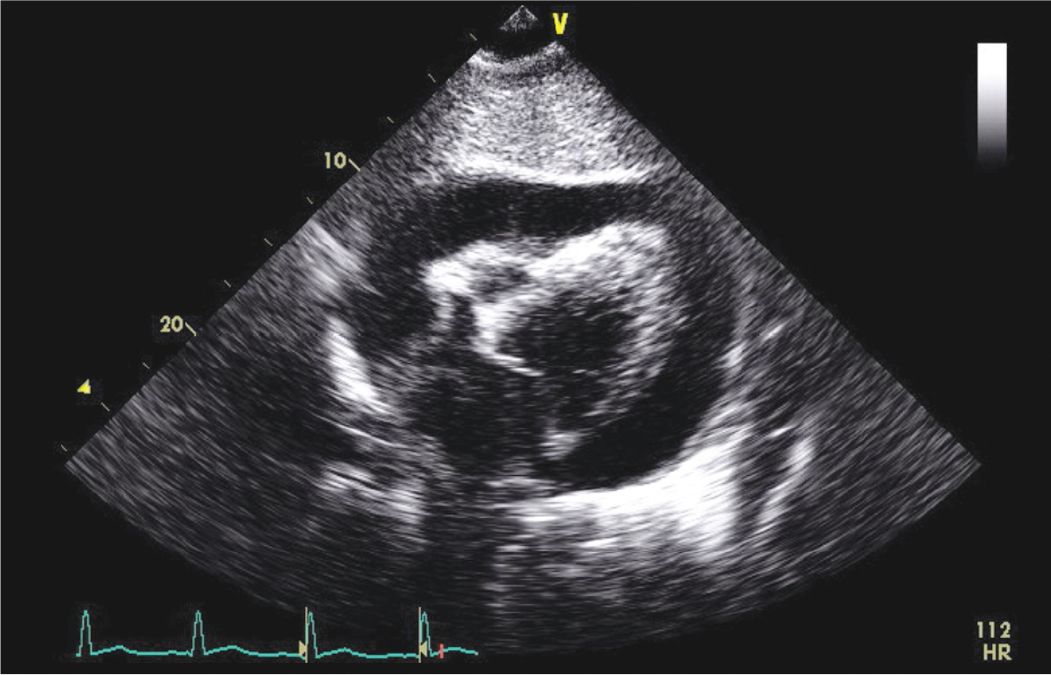

In the emergency department, his blood pressure is 124/82 mm Hg, and his pulse is 110 beats/minute. He is mildly tachypneic and is sitting forward in bed. Auscultation of his heart reveals a tachycardic, but regular, rate. He has a normal S1 and S2, and a soft pericardial friction rub. An electrocardiogram (ECG) done in the emergency department is shown in Figure 6-2-1. An echocardiogram was also ordered by the ED staff. It demonstrated no significant pericardial fluid (Figure 6-2-2). He was admitted to the hospital, treated with ibuprofen and colchicine, and discharged after a brief period of observation. His symptoms resolved quickly, and he has had no clinical recurrence.

FIGURE 6-2-1 Electrocardiogram (ECG) of a patient with acute pericarditis. This ECG shows classic findings of pericarditis, including diffuse ST elevation, PR depression (best seen in lead aVF), as well as ST depression and PR elevation in aVR.

FIGURE 6-2-2 Echocardiogram of the patient described in the text presenting with acute pericarditis. Note the absence of any pericardial effusion in the subcostal view.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

• Acute pericarditis is the most common disorder involving the pericardium.

• The exact incidence and prevalence of acute pericarditis is not known, but as many as 5% of patients presenting to the emergency department with chest pain (without myocardial infarction) are thought to be due to acute pericarditis,1 and 1% of ST elevations on ECG are found to be due to acute pericarditis.2

• Acute pericarditis can occur at any age, but it is most prevalent in men aged 20 to 50 years.

ETIOLOGY AND PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

• Roughly 70% to 80% of cases of acute pericarditis are idiopathic. Most of these are presumed to be of a viral etiology.3

• Other causes include infections (viral, tuberculosis, bacterial), neoplastic, uremic, radiation induced, or autoimmune.

• Irritation from the underlying condition causes the pericardial serosa to become acutely inflamed, which leads to the infiltration of polymorphonuclear cells and the overproduction of pericardial fluid.

• This inflammation leads to pain, and the overproduction of pericardial fluid can lead to pericardial effusion (usually mild to moderate in size).

• Acute pericarditis only rarely presents with effusions large enough to cause tamponade.

• Chronic inflammation can lead to fibrosis of the pericardium and can cause constrictive pericarditis.

DIAGNOSIS

• The diagnosis of acute pericarditis is made on clinical grounds by suggestive history and physical exam. Electrocardiographic findings can help support the diagnosis.

• Echocardiography may demonstrate a pericardial effusion, a common complication of acute pericarditis. It is important to note that the absence of an effusion does not preclude the diagnosis, nor does the presence of a pericardial effusion confirm the diagnosis of acute pericarditis.

• Caution should be paid as acute pericarditis has presenting factors and electrocardiographic findings that can overlap with life-threatening conditions such as acute myocardial infarction and pulmonary embolism (see Differential Diagnosis).

• The diagnosis of acute pericarditis is made by the presence of two or more of the following:

![]() Typical chest pain.

Typical chest pain.

![]() A pericardial friction rub.

A pericardial friction rub.

![]() Typical ECG changes.

Typical ECG changes.

![]() A new, or worsening pericardial effusion by echocardiography provides further evidence of an acute pericardial process (Figures 6-2-3 and 6-2-4).

A new, or worsening pericardial effusion by echocardiography provides further evidence of an acute pericardial process (Figures 6-2-3 and 6-2-4).

FIGURE 6-2-3 Acute pericarditis in a different patient with a small to moderate pericardial effusion.

FIGURE 6-2-4 Subcostal view of another patient who presented with fever, chest pain, and hypotension. His ECG was consistent with pericarditis. The echocardiogram demonstrated evidence of cardiac tamponade. He was diagnosed with aortic valve endocarditis with an abscess and underwent emergent surgery with AV replacement.

CLINICAL FEATURES

• Greater than 95% of cases of acute pericarditis present with substernal chest pain.4

• Chest pain is usually burning or stabbing in quality and usually develops over minutes or hours.

• The chest pain is generally worse when lying flat, or with deep inspiration, and improves with sitting upright and/or leaning forward, as the pericardial sac hangs away from the vertebral column in this position.

• Fever can be the initial presentation, or can be present in addition to chest pain.

• Patients are usually tachycardic and can also be tachypnic.

• A pericardial friction rub is present in about 35% of presenting cases.4

LABORATORY EVALUTION

• Patients can have high sedimentation rates and high C-reactive protein levels due to the presence of inflammation. Inflammatory markers are very sensitive, but they are also very nonspecific for acute pericarditis.

• Some patients can have elevated troponin levels suggesting some degree of concomitant myocarditis, but this test is also very nonspecific.

ELECTROCARDIOGRAPHY

• An electrocardiogram (ECG) of a patient with acute pericarditis is shown in Figure 6-2-1. Classic ECG findings for acute pericarditis include diffuse ST elevation, diffuse PR depression (especially in the inferior leads), and PR elevation in aVR. Tachycardia is frequently present. While pericarditis usually affects the ECG diffusely, local ECG changes can be seen when pericardial inflammation is isolated to a small portion of the pericardium.

ECHOCARDIOGRAPHY

• Patients with acute pericarditis will often have a normal echocardiogram, or will have abnormalities unrelated to acute pericarditis.

• The most common echocardiographic abnormality associated with acute pericarditis is a pericardial effusion (Figure 6-2-3), which is present in about 60% of cases of acute pericarditis.4 The absence of a pericardial effusion (as in the present case) does not exclude the possibility of acute pericarditis, but the presence of a pericardial effusion can be helpful in supporting the diagnosis.

OTHER DIAGNOSTIC MODALITIES

• Computed tomography (CT) scan and cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can both show thickening of the pericardium in chronic pericardial disease, but have not been evaluated for clinical utility in the evaluation of acute pericarditis.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree