Fig. 1.1

Causes of death in men and women with HFrEF vs. HFpEF (From Lee et al. [14]. Reprinted with permission from Wolters Kluwer Health)

A similar analysis of decedents with heart failure from Olmstead County reported that 43 % of deaths were non-cardiovascular and preserved ejection fraction was associated with a marginally lower risk of cardiovascular death [15]. In contrast, the leading cause of death in subjects with HFrEF was coronary heart disease (43 %). The proportion of cardiovascular deaths decreased significantly from 69 in 1979–1984 to 40 % in 1997–2002 among subjects with preserved left ventricular ejection fraction, in contrast to a more modest change among those with HFrEF from 77 to 64 % [15].

Palliative Care in Cardiovascular Illness

Patients dying with cardiovascular disease exhibit both high rates of hospital use and geographic variations in care patterns. In a retrospective analysis of Medicare beneficiaries with heart failure who died, 80 % were hospitalized within the last 6 months of life, although the majority of hospitalizations were for diagnoses other than heart failure [16]. Over 8 years, the mean length of stay in hospital remained constant, yet the average length of stay in intensive care increased from 3.5 to 4.6 days and the percentage of patients discharged from hospital to hospice care rose. Accordingly, the costs incurred to Medicare by patients with heart failure near the end of life increased by 11 % between 2000 and 2007 after adjustment for age, sex, race, comorbid conditions, and geographic region [16]. It has been estimated that the average cost of heart failure care in the last 6 months of life is more than five-fold the per-capita health care expenditure [17]. The staggering impact of these large per patient numbers is compounded by the expected rise in the prevalence of heart failure as a population with a high burden of cardiovascular disease and its risk factors continues to age [18].

Over the past decade, there has been increasing awareness of the need to include palliative care in heart failure treatment plans. In a 2004 survey of clinically active members of the Heart Failure Society of America, two-thirds of respondents had not referred a single patient for palliation in the preceding 6 months and almost 88 % had referred less than six patients over that time period [19]. While this survey was limited by a poor response rate of 24 %, such results support the notion that “cardiologists often focus on what can be done rather than what should be done, and the latter consideration may be neglected in the midst of therapeutic optimism” [20]. There has been little change in the utilization of costly invasive cardiac procedures in the last 6 months of life, including cardiac catheterization, pacemaker or implantable cardioverter-defibrillator implantation, and coronary artery bypass graft surgery, while the use of echocardiography has increased within the last 6 months of life of patients with heart failure [16].

The utilization of palliative care or hospice services is relatively low among patients with cardiovascular disease relative to other terminal illnesses such as cancer. In one population of medically insured patients, only 20 % of patients with end-stage heart failure were referred to hospice compared to 51 % of cancer patients. Opiate prescriptions have been proposed as a surrogate for palliative treatments and were observed to be used in 22 % of heart failure compared with 46 % of cancer patients [21]. Temporally, there has been only modest uptake of hospice and/or palliative care among patients with end-stage heart failure [21–23], despite the class I recommendation that palliative/hospice care referral should be offered to patients with end-stage heart failure in the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association [24] and other international guidelines [25, 26]. Certain characteristics appear to predict a greater likelihood of referral to hospice or palliation in advanced heart failure: younger age, male gender, white ethnicity, higher income, and dialysis dependence [21–23, 27]. In addition, hospitals in greater compliance with heart failure performance measures may be more likely to refer patients with advanced heart failure to hospice [22].

There are multiple potential explanations for the persistently aggressive care and low rates of utilization of palliative care and hospice services among patients with heart failure and other cardiovascular diseases:

Palliation is not traditionally part of the ‘therapeutic culture’ of cardiology.

Palliative care is closely aligned with oncology and in some countries funding is aligned with cancer services, leading to non-acceptance of cardiac patients for palliative care.

There is a paucity of evidence-based palliative care of patients with cardiovascular disease.

A significant proportion of patients succumb to sudden cardiac death thus limiting the opportunity for provision of palliative care.

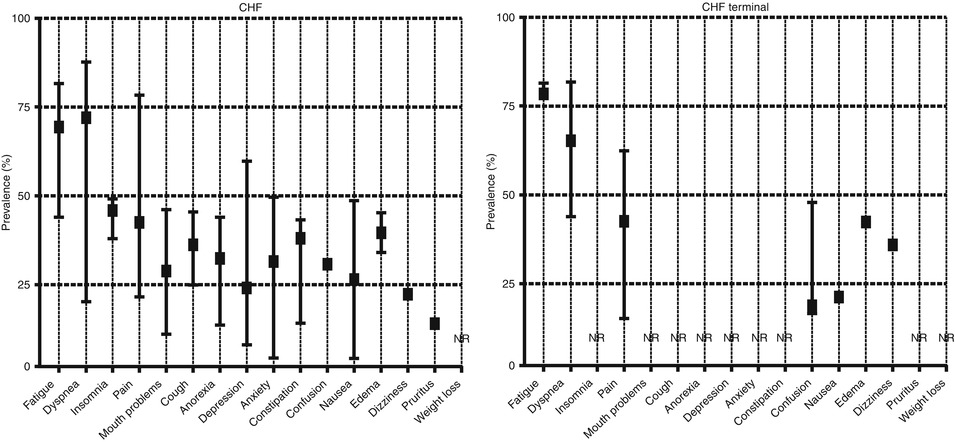

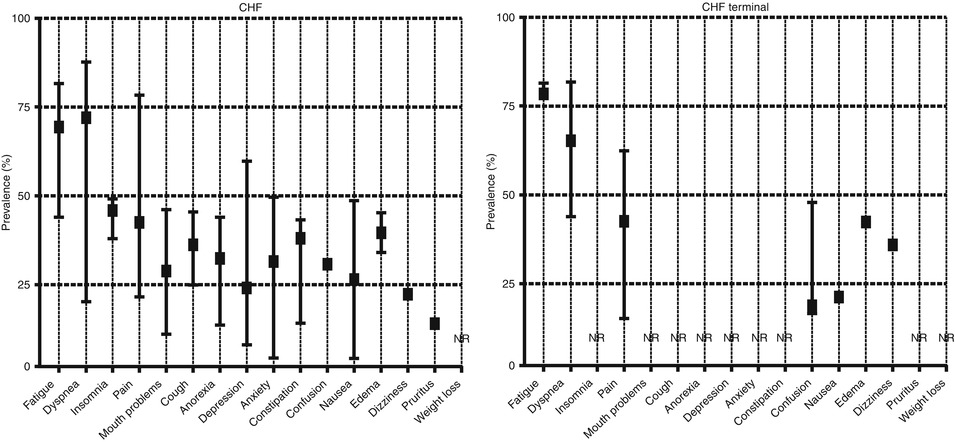

While cardiac specialists are familiar with the cardinal features of cardiovascular disease, patients may develop a multitude of other symptoms that markedly decrease their quality of life. Comparisons of outpatients with heart failure and advanced cancer reveal an equivalent burden of physical and depressive symptoms; patients with worse heart failure functional class had greater physical symptom burden, higher depression scores, and lower spiritual well-being than patients with advanced cancer [32]. As shown in Fig. 1.2, heart failure patients experience numerous symptoms, which are not part of the usual cardiovascular health evaluation. Moreover, the symptom burden in heart failure patients is an important prognostic factor. In the Carvedilol or Metoprolol European Trial (COMET), the symptom of breathlessness remained significantly associated with death while fatigue was the primary predictor of worsening heart failure in multivariate analysis [34]. Moreover, anxiety and depression have been consistently linked to worse outcomes in cardiovascular illness, with some of the postulated mechanisms involving detrimental alterations in physiology [35, 36].

Fig. 1.2

Minimum, maximum and median prevalence of reported daily symptom burden in patients with end-stage congestive heart failure (CHF, left upper panel). NR not reported (From Janssen et al. [33]. Reprinted with permission from SAGE Publications)

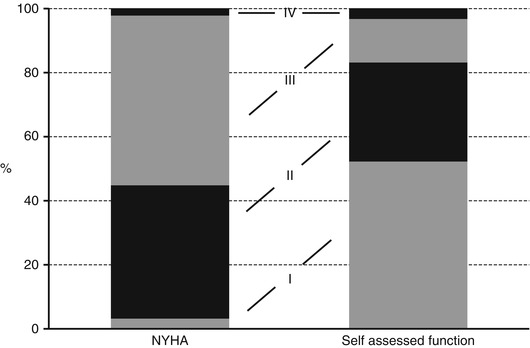

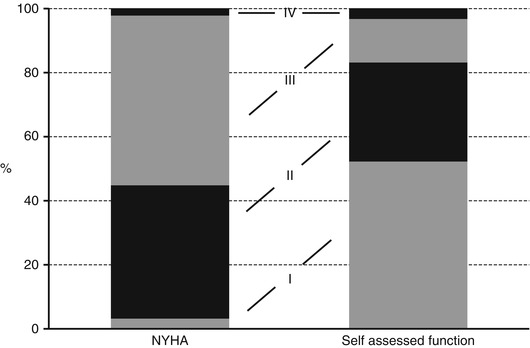

Physicians and nurses often incompletely assess the symptom burden outside the cardinal manifestations of cardiovascular disease [37, 38]. There is also a significant gap between physician and patient perspectives on the degree of functional limitation, as shown in Fig. 1.3. Commonly used scales such as the NYHA functional classification do not account for other limiting symptoms such as pain, depression, or nausea. Tools that provide a global assessment of symptom burden to allow for effective management include the Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale [40], Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale [41, 42], Quality-of-Life at the End of Life [43], the McGill Quality of Life Questionnaire [44], and the Palliative Performance Scale [45].

Fig. 1.3

Patients’ self-assessed functional classification compared to conventional NYHA classification (From Ekman and Cleland [39]. Reprinted with permission from Oxford University Press)

Models of Care at the End of Life

At end of life, patients receiving palliative care services often also receive improved holistic care, continuity of care, more focused goals of care, and attain better reported measures of anxiety, depression, global health status, and physical, social, cognitive, and emotional function [46, 47]. Paradoxically, observational studies have shown longer survival in patients referred for hospice care [48]. However, HF patients’ multiple active cardiac issues may be best managed by close collaboration between the different disciplines [49, 50]. Primary health care providers shoulder a significant burden of heart failure patients’ care to facilitate home deaths [51].

However, the impact of hospice referrals on costs is unclear, with conflicting reports from different studies [52–54]. While rates of hospitalization, days in intensive care, and invasive procedures are reduced, the use of hospice increased overall Medicare expenditures compared to non-hospice care after 154 days for approximately 15 % of HF patients [54]. A slightly larger percentage of patients with heart failure referred for hospice care are alive 6 months after referral than patients with cancer [54, 55]. In fact 19 % of patients with heart failure are discharged alive from hospice compared with 11 % of those with cancer diagnosis [55]. Alternate models including outpatient palliative care may be needed for patients with cardiovascular disease [47, 55–60].

Estimating Survival Among Patients with Cardiovascular Disease Near End of Life

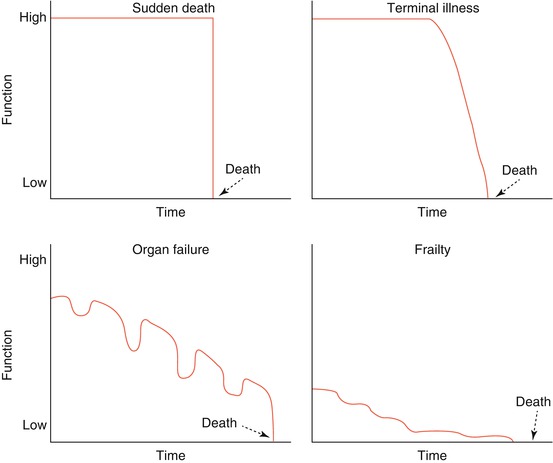

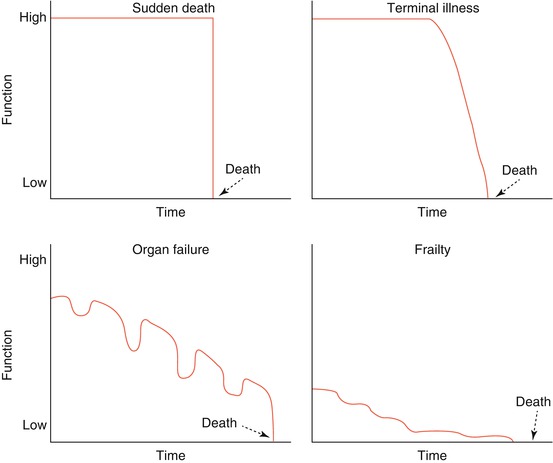

One of the major reasons for the difficulty in prognosticating end of life is because of the stochastic nature to cardiovascular deaths. Changes in functional status are often unpredictable and not closely linked with imminent death [61, 62]. Patients also have misperceptions about their prognosis when compared to estimates of their life expectancy based on multivariate models [62, 63]. The trajectory of functional decline in patients dying with heart failure is often different from cancer, being characterized by episodes of acute worsening followed by an often rapidly progressive terminal phase [64]. Of four hypothetical trajectories near end of life: sudden death, terminal illness, organ failure, and frailty (see Fig. 1.4), heart failure is grouped with organ failure [66]. However, only a minority of patients follow the supposedly ‘typical’ heart failure trajectory [61], and many older patients with heart failure follow a trajectory that more closely mirrors the ‘frailty’ pattern [67, 68]. Patients with ischemic heart disease are often placed in an ‘other’ or ‘unclassified’ group where patients showed a pattern of modest and gradual decline in independence during the final year of life.

Fig. 1.4

Theoretical trajectories of death (From Lunney et al. [65]. Reprinted with permission from John Wiley and Sons)

Prognostication

Selected tools for prognosticating heart failure patients with end-stage disease are shown in Table 1.1. In the general practice setting, predictors of 1-year mortality include male sex, NYHA class III or IV, age ≥85 years, and cancer [75]. Interestingly, using these broad criteria as a guide, general practitioners were able to identify those who died within 12 months with 79 % sensitivity but only 61 % specificity. Challenges of prognostication are also present in specialty clinics. Predictive models based on ambulatory clinic or controlled trial-based cohorts include the Seattle Heart Failure Model (SHFM), the HF Survival Score (HFSS), and the Gold Standards Framework Prognostic indicator (details in Table 1.1). Validation exercises of these models, however, underscore the current state of difficulty with predicting death for those who could be referred to palliative care.

Table 1.1

Prognostic tools to identify heart failure patients approaching end of life

Heart failure | Reported measures of validity | |

|---|---|---|

EFFECT Heart Failure Mortality Prediction | In-patient demographic and lab data at admission provide risk stratification for death within 30 days and 1 year (available online at http://www.ccort.ca/Research/CHFRiskModel.aspx) [69] | C-statistic 0.82 for in-hospital death, 0.80 for 30-day mortality and 0.77 for 1-year mortality [70] |

The Seattle Heart Failure Model | Demographic, lab, device and medication data provide 1, 2 and 3 year survival estimates (available online at http://depts.washington.edu/shfm/app.php) [71] | C-statistic 0.73 |

Heart Failure Survival Score | Ambulatory patient risk stratification, including peak vO2, developed to aid cardiac transplant decision-making [72] | Event-free survival rate at 1 year in the validation sample was 88 ± 4, 60 ± 6, and 35 ± 10 % in the low-, medium-, and high-risk strata, respectively |

Gold Standards Framework | 4 components: NYHA class III or IV, The surprise question: “Would you be surprised if this patient died in the next 6–12 months?”, Repeated heart failure hospitalizations, and difficult physical or psychological symptoms despite optimized tolerated therapy [73] | 2 or more of 4 criteria: sensitivity 83%, specificity 22% |

RADbound indicators of PAlliative Care Needs (RADPAC) | 1. NYHA Class IV | N/A |

2. >3 hospital admissions per year | ||

3. >3 severe exacerbations of heart failure per year | ||

4. Moderately disabled; dependent. Requires considerable assistance and frequent care (Karnofsky-score ≤50 %) | ||

5. Increasing weight and non-responsive to increased doses of diuretics | ||

6. General deterioration (edema, orthopnea, dyspnea) | ||

7. The patient mentions ‘end of life approaching’ [74] | ||

Repeated hospitalization is a significant predictor of adverse prognosis in patients with heart failure [76, 77]. Predictive models based on data at the time of hospitalization, such as the Enhanced Feedback For Effective Cardiac Treatment (EFFECT-HF) risk score [69], which is comprised of simple clinical factors predict short and long-term mortality for heart failure patients with either HFrEF or HFpEF [68, 78]. In a comparison of six different models [69, 71, 79–82] tested in a cohort of patients who ultimately died with heart failure, predicted mortality was highest using the EFFECT-HF model [78]. The subset of covariates, which included serum urea nitrogen, systolic blood pressure, peripheral artery disease, and hyponatremia were especially predictive of mortality [83]. The presence of three or more of these risk factors was associated with 6-month mortality rates as high as 66.7 % [83]. The role of biomarkers such as brain natriuretic peptide, for the identification of patients at end of life has not been delineated.

Objective measures of decreased functional status, or self-reported poor health, may also provide prognostic information in heart failure. Low functional exercise capacity, defined as ≤300 m walked during 6 min, was associated with 1.8-fold increased risk of death, but is a poor standalone indicator of prognosis [84–86]. In addition, low self-reported physical functioning, defined as a score below 25 on the Short Form Health Survey (SF-12), was also shown to be associated with a 1.6-fold increase in risk of death. However, the much more simple measure of poor self-rated general health, corresponded to a 2.7-fold increase in risk of death compared with good to excellent self-reported general health [84]. Functional status information is an important component of the RADbound indicators of Palliative Care Needs and the Gold Standards Framework, which may be useful to identify patients with heart failure approaching end of life (see Table 1.1).

Generic aids to identifying patients approaching end of life include the ‘surprise question,’ which is a component of the Gold Standards Framework, and the Palliative Performance Scale (see Table 1.2). However, these have not been studied in end-stage heart failure. While older age is associated with a substantially increased risk of death, the frail elderly are at a particularly heightened risk. Few predictive models have included frailty as a parameter, although this metric is rapidly gaining interest. Among frail elderly patients aged 75 years or older with refractory (stage D) heart failure, symptoms of peripheral edema or pain, and need for nitrate therapy were found to predict mortality, whereas the ability to sit in a chair was associated with improved survival [89].

Table 1.2

Generic aids for identifying patients at end of life

Generic | |

|---|---|

Surprise question: “Would I be surprised if this patient died in the next 6–12 months?” | Increased odds of dying if answer is “No”. Validated in cancer and renal dialysis patients to date [75], and is a component of the Gold Standards Framework |

Palliative Performance scale (PPS) | Physical status rating (by clinician) out of 100 % (ability in activity, ambulation, self-care, oral intake and level of consciousness), lower scores associated with poorer prognosis. Developed in cancer, some evidence for non-cancer use (available online at www.victoriahospice.org/sites/default/files/imce/PPS%20ENGLISH.pdf) [87, 88] |

Contrary to common perception, refractory stable angina does not independently predict a high risk of death in the near future. Among those with chronic ischemic heart disease and refractory angina, overall 1-year mortality rate was only 3.9 %, but the presence of diabetes, chronic renal disease, left ventricular dysfunction and heart failure increased the risk of death [90]. While methods have not been developed in those with isolated chronic ischemic heart disease, models for end of life estimation have been proposed for patient subsets with myocardial infarction (see Table 1.3). The overlap in predicted risk factors for death in those with refractory coronary artery disease and end-stage heart failure suggest that a common set of criteria may exist [90].

Table 1.3

Prognostic tools to identify coronary disease patients approaching end of life

Myocardial infarction | Reported measures of validity | |

|---|---|---|

GRACE risk score | Extensively validated risk score among patients with myocardial infarction. Available online at: http://www.outcomes-umassmed.org/GRACE/default.aspx [91, 92] | 78 % sensitivity and 89 % specificity for 6-month mortality when combined with Gold Standards framework [93] |

Karnofsky Performance status | Functional scale, similar to PPS; one study of use in prognosis with acute MI (http://www.hospicepatients.org/karnofsky.html) [94] | A KPS score <8 (scale from 1 to 10) 3 weeks before the index infarction was associated with a higher incidence of congestive heart failure, in-hospital cardiac arrest, and mortality during hospitalization |

Impact of Comorbidities on Prognosis

The burden of non-cardiac comorbidities in patients with heart failure has a complementary impact on patients’ prognosis. This is increasingly relevant as the population ages, since a larger proportion of patients with heart failure may have accumulated diseases that could have substantial impact on their overall prognosis. From the standpoint of selecting patients for palliation, comorbidities that are minimally-modifiable may be most useful. One of the better studied comorbidities is worsened renal function; however, comorbid cancer and anemia are also common and may not be amenable to curative intervention (see Table 1.4). Other prognostic factors that have been associated with death or persistently unfavorable quality of life include lower systolic blood pressure [22, 23], hyponatremia, tachycardia, and diabetes [101].

Table 1.4

Impact of common comorbidities in survival of patients with heart failure

Comorbidity | Prevalence | Impact on prognosis |

|---|---|---|

Renal dysfunction | Any renal impairment: up to 70 % | |

Moderate to severe renal impairment: up to 29 % [95] | ||

Cancer | 22 %, with a hazard ratio of 1.68 relative to patients without heart failure [97] | Adjusted hazard ratio of 1.56 for death after adjustment for age, sex, and comorbidities [97] |

Anemia | Any anemia 37 % [98] |

Therapeutic Considerations Near End of Life

Increasing diuretic dose may be a useful universal marker of prognosis. In a study of 4,406 elderly patients discharged after heart failure hospitalization [102], the prescription of higher furosemide doses (≥120 mg/day) was more common among patients with higher creatinine levels, diabetes, atrial fibrillation, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, hypotension, cardiomegaly, hyponatremia, and lower hemoglobin levels. After extensive multivariable adjustment, exposure to higher furosemide dose was found to be predictive of death, hospitalization and renal dysfunction over 5-year follow-up. Intolerance of angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors or beta-adrenoreceptor antagonists is a poor prognostic sign; tolerance of heart failure therapy is one of the predictors of discharge alive from hospice among patients with heart failure [55, 101, 103].

A relevant consideration is the appropriate continuation or termination of medications or device therapy in a patient with advanced cardiovascular disease [104–106]. Patients at the highest risk of adverse outcomes have larger absolute benefit from interventions. However, these patients are often left undertreated resulting in a ‘risk-treatment mismatch’. For example, patients with heart failure at greatest risk of death are least likely to receive ACE inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs), and beta-adrenoreceptor antagonists [104].

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree