Chapter 71 Disorders of the Mediastinum

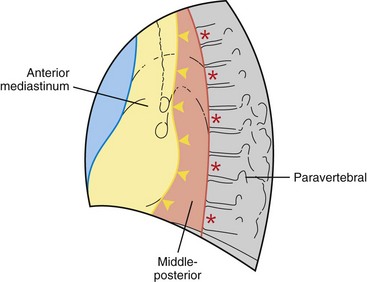

This chapter divides the mediastinum into anterior, middle-posterior, and paravertebral compartments (Figure 71-1). The anterior mediastinum is defined by an imaginary line drawn along the anterior trachea and posterior cardiac border on a lateral chest radiograph. The paravertebral compartment is located posterior to an imaginary line drawn to connect the anterior aspects of the thoracic vertebrae. The middle-posterior mediastinum is the compartment located between the anterior and paravertebral compartments. Note that the paravertebral regions do not form part of the mediastinum proper.

Overview of Mediastinal Masses

In adults, approximately 65% of primary mediastinal lesions are located in the anterior mediastinum, 10% in the middle-posterior mediastinum, and 25% in the paravertebral compartment. In contrast, approximately 38% of childhood mediastinal lesions are located in the anterior, 10% in the middle-posterior, and 52% in the paravertebral compartment (Table 71-1).

Table 71-1 Compartmental Classification of Mediastinal Disorders

| Abnormality/Source | Disorder/Abnormality |

|---|---|

| Anterior Mediastinum | |

| Disorders of thymus gland | Thymomas: thymic carcinoma, thymic carcinoid, thymolipoma, thymic cyst, thymic hyperplasia Lymphoma: Hodgkin disease, non-Hodgkin lymphoma Germ cell neoplasms Benign: Mature teratoma Malignant: Seminoma, nonseminomatous germ cell neoplasms |

| Thyroid | Intrathoracic goiter |

| Parathyroid | Parathyroid adenoma |

| Pericardial cysts | |

| Miscellaneous | Mesenchymal neoplasms (lipoma, liposarcoma, angiosarcoma, leiomyoma) Cystic hygroma (mediastinal lymphangioma) |

| Middle-Posterior Mediastinum | |

| Lymph node enlargement | Lymphoma Benign mediastinal lymphadenopathy: Granulomatous disease, infectious (tuberculosis, fungal infections) Noninfectious (sarcoidosis, silicosis) Miscellaneous causes: Castleman disease Amyloidosis Metastatic mediastinal lymphadenopathy Lung, renal cell, gastrointestinal, and breast carcinoma |

| Cysts | Foregut cysts Bronchogenic and enteric cysts |

| Esophageal disorders | Achalasia, benign tumors, esophageal carcinoma, esophageal diverticulum |

| Vascular lesions | Aneurysms, hemangioma |

| Miscellaneous | Herniations, pancreatic pseudocyst |

| Paravertebral Lesions | |

| Neurogenic neoplasms | Peripheral nerve neoplasms: Schwannoma, neurofibroma Malignant peripheral nerve sheath neoplasm Sympathetic ganglia neoplasms: Ganglioneuroma, ganglioneuroblastoma, neuroblastoma Paraganglionic neoplasms: Pheochromocytoma, paraganglioma |

| Spinal | Lateral thoracic meningocele Paraspinal abscess (Pott disease) |

| Miscellaneous | Extramedullary hematopoiesis Thoracic duct cysts |

The initial evaluation of patients with mediastinal abnormalities includes a detailed history and physical examination to discover specific symptoms and signs of various mediastinal disorders and associated diseases (Table 71-2). Posteroanterior (PA) and lateral chest radiography, computed tomography (CT), and occasionally magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and fluorine 18 (18F) fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) positron emission tomography (PET) with CT are used for lesion detection and characterization, usually followed by an invasive procedure for tissue diagnosis. However, some mediastinal lesions have a characteristic radiologic appearance, and biopsy may be unwarranted or contraindicated, as in congenital cysts and vascular lesions, respectively. In addition, laboratory evaluation to include a complete blood count, electrolytes, renal and liver function tests, and serologic tests for various autoantibodies and tumor markers may be useful in the initial evaluation and in posttherapy follow-up.

Table 71-2 Mediastinal Disorders: Constitutional and Paraneoplastic Findings

| Diseases | Clinical Findings |

|---|---|

| Lymphoma | Fever, weight loss, night sweats, pruritus, hypercalcemia |

| Thymoma | Myasthenia gravis, hypogammaglobulinemia, pure red cell aplasia |

| Thymic carcinoid secretion | Cushing syndrome, syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone |

| Germ cell neoplasm | Gynecomastia, Klinefelter syndrome, hematologic neoplasms |

| Intrathoracic goiter | Hyper/hypothyroidism |

| Pheochromocytoma | Hypertension, hypercalcemia, polycythemia, Cushing syndrome |

| Autonomic ganglia neoplasm | Opsomyoclonus, hypertension, watery diarrhea, Horner syndrome |

| Sarcoidosis | Hypercalcemia |

Diseases of Anterior Mediastinum

Mediastinal Neoplasms

Thymoma

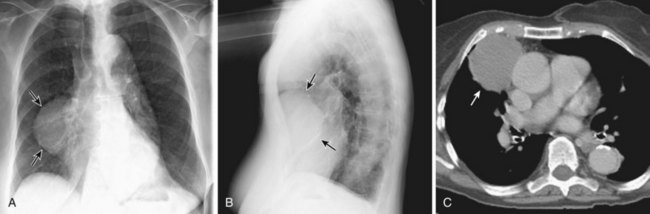

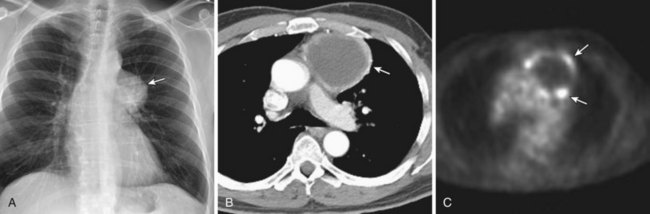

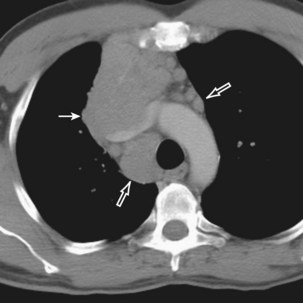

Thymomas manifest on radiography as rounded, well-circumscribed, unilateral, anterior mediastinal masses (Figure 71-2). They are typically located anterior to the aortic root but may be found anywhere from the thoracic inlet to the diaphragm and rarely in the neck. On cross-sectional imaging, thymomas are often homogeneous, soft tissue masses but may exhibit heterogeneity because of cystic change, hemorrhage, or necrosis, especially in large neoplasms. Drop metastases to the ipsilateral pleura, pericardium, or upper abdomen through a diaphragmatic hiatus are well documented and represent invasive disease (Figure 71-3). Pleural drop metastases may encase the lung and mimic diffuse malignant mesothelioma, although associated pleural effusion is infrequent. Lymph node and hematogenous metastases are rare. Mediastinal invasion may be detected with CT and may manifest as an irregular tumoral surface, contralateral extension of thymoma across the midline, and obvious invasion of mediastinal fat and structures. Imaging evidence of local invasion must be correlated with microscopic evidence of capsular transgression and tissue invasion, because encapsulated thymomas may produce fibrous adhesions to adjacent structures. MRI is more sensitive than CT in the detection of vascular invasion. When evaluating a thymic mass, PET-CT may be useful for depicting tumoral invasion, differentiating subgroups of thymic epithelial neoplasms, and staging extent of disease. The maximum standard uptake values (SUVs) of thymoma are typically lower than those of thymic carcinoma. Guided needle biopsy, mediastinotomy, mediastinoscopy, and video-assisted thoracoscopy may establish the diagnosis. However, histologic diagnosis before excisional surgery may not be required in classic cases of thymoma.

Thymic Carcinoma

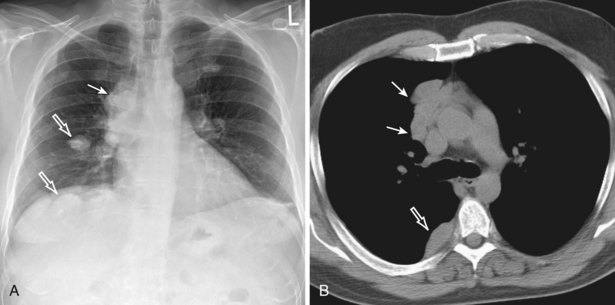

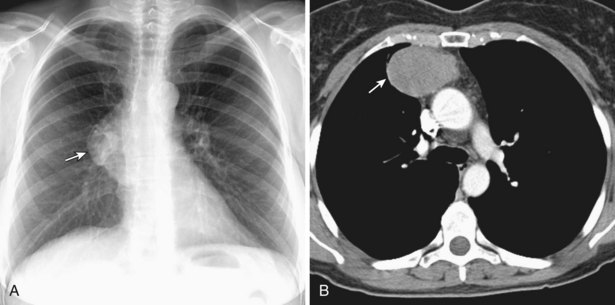

Thymic carcinomas are a heterogeneous group of aggressive epithelial malignancies with a tendency for early local invasion and distant metastases. Men are more often affected (mean age, 46 years). The Revised 2004 WHO classification of thymic epithelial neoplasms describes thymic carcinomas as “nonorganotypic” malignancies (type C) that resemble carcinomas of extrathymic origin, such as lung carcinomas. By traditional histopathologic classification, the two most common cell types are squamous cell and lymphoepithelial-like carcinoma. Unlike thymoma, thymic carcinoma has malignant histologic features and typically manifests as a large, poorly defined, infiltrative, anterior mediastinal mass, frequently with regional lymph node and pulmonary metastases, and pleural and/or pericardial effusions (Figure 71-4).

Thymic Carcinoid

Thymic carcinoid is a rare, aggressive neuroendocrine neoplasm that typically affects men in the fourth and fifth decades of life. These are large, symptomatic, locally invasive neoplasms with frequent distant metastases. Approximately 35% of affected patients develop endocrine abnormalities caused by ectopic hormone production, most often Cushing syndrome. Multiple endocrine neoplasia syndrome type I (MEN-I) may also occur. However, the syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion (SIADH) and the carcinoid syndrome are rare. Radiologically, thymic carcinoid is a large, lobular, heterogeneous, and usually invasive anterior mediastinal mass indistinguishable from thymic carcinoma or thymoma (Figure 71-5). There may be associated intrathoracic metastatic lymphadenopathy. Surgical resection, when feasible, is the treatment of choice, and response to chemotherapy and radiotherapy is poor.

Hodgkin Disease

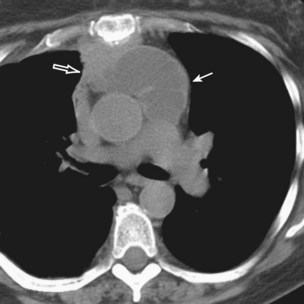

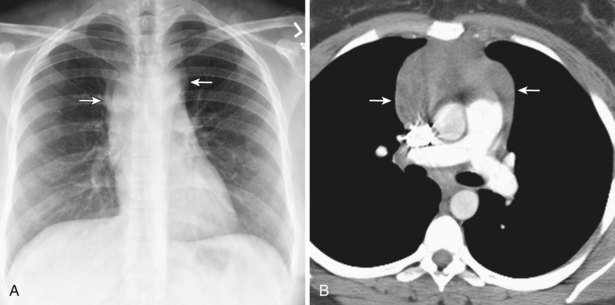

Radiologically, most patients with HD have bilateral, asymmetric, mediastinal lymphadenopathy, which frequently involves the prevascular and paratracheal lymph nodes and rarely the posterior mediastinal or juxtacardiac lymph nodes. Nodular sclerosis HD can manifest as a discrete, unilateral anterior mass (Figure 71-6) or bilateral mediastinal mass (Figure 71-7) or as large, lobular, coalescent lymphadenopathy in the anterior mediastinum (Figure 71-8). Invasion, compression, and displacement of mediastinal structures, lung, pleura, and chest wall may occur. Affected lymph nodes usually exhibit homogeneous attenuation but may be heterogeneous because of hemorrhage, necrosis, or cystic change. De novo lymph node calcification rarely occurs but may develop 1 to 5 years after radiation therapy. Direct invasion of the lung occurs in 8% to 14% of untreated patients and is usually associated with hilar lymphadenopathy. The diagnosis is established with either core biopsy or surgical excision of affected palpable lymph nodes or masses found on imaging.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree