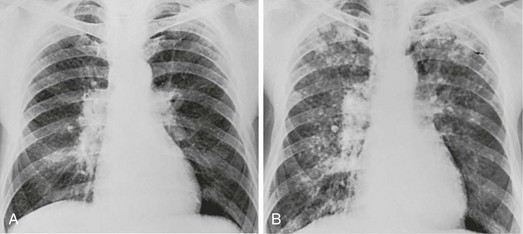

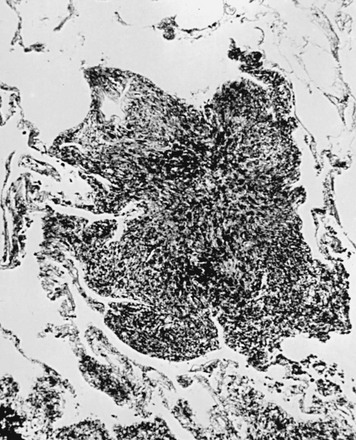

10 This chapter focuses on several of the major categories of diffuse parenchymal (interstitial) lung disease for which an etiologic agent has been identified. The general principles discussed in Chapter 9 apply to most of these conditions, and the features emphasized here are those peculiar to or characteristic of each cause. Considering the vast number of diffuse parenchymal lung diseases, this chapter only scratches the surface of information available. When a physician is confronted with a patient having a particular type of diffuse parenchymal lung disease, it is best to relearn the details of the disease at that time. Although the pathogenesis of silicosis is not known with certainty, theories have focused on the potential toxicity of silica for macrophages. Silica particles in the lower respiratory tract are phagocytosed by alveolar macrophages. Freshly cut silica particles are more pathogenic than older particles. This property is thought to be due to the increased redox potential of the fresh surface, which is highly reactive. After engulfing the silica particle, the macrophage is activated and releases inflammatory mediators, including tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, interleukin-1, and arachidonic acid metabolites. Phagocytosis of silica particles leads to apoptotic cell death, and toxic silica particles are released that are capable of repeating the process after they are reingested by other macrophages. With their activation and destruction, the macrophages release chemical mediators that initiate or perpetuate an alveolitis, eventually leading to development of fibrosis. Pathologically, the inflammatory process initially is localized around the respiratory bronchioles but eventually becomes more diffuse throughout the parenchyma. The ongoing inflammatory process causes scarring and results in characteristic acellular nodules called silicotic nodules that are composed of connective tissue (Fig. 10-1). At first the nodules are small and discrete. With disease progression they become larger and may coalesce. Silicotic nodules are believed to be areas in which the cycle of macrophage ingestion, activation, destruction, and release of the toxic silica particles occurs. The most common radiographic appearance of silicosis is notable for small, rounded opacities or nodules. This pattern is described as simple chronic silicosis. Uncommonly, the nodules become larger and coalescent, in which case the pneumoconiosis is called complicated; the term progressive massive fibrosis has also been used (Fig. 10-2). As a general rule, in patients with silicosis the upper lung zones are affected more heavily than the lower zones. Enlargement of the hilar lymph nodes, which frequently calcify, may be seen. In addition to the potential problem of progressive pulmonary involvement and eventual respiratory failure, abnormal immune regulation is associated with silicosis. Patients are at increased risk for certain autoimmune diseases including rheumatoid arthritis and systemic sclerosis. In addition, patients with silicosis are particularly susceptible to infections with mycobacteria, perhaps because of impaired macrophage function. The specific organisms may be either Mycobacterium tuberculosis, the etiologic agent for tuberculosis, or other species of mycobacteria, often called atypical or nontuberculous mycobacteria (see Chapter 24). The pathologic hallmark of CWP is the coal macule, which is a focal collection of coal dust surrounded by relatively little cellular infiltration or fibrosis (Fig. 10-3). The initial lesions tend to be distributed primarily around respiratory bronchioles. Small associated regions of emphysema, termed focal emphysema, may be seen. Asbestos has been widely used because of its thermal and fire resistance. It is a fibrous derivative of silica, termed a fibrous silicate. It is a naturally occurring mineral that, because of its long narrow shape, can be woven into cloth. Among the health hazards it presents are the development of diffuse interstitial fibrosis, benign pleural plaques and effusions, and the potential for inducing several types of neoplasm, particularly bronchogenic carcinoma and mesothelioma. These latter problems are discussed in Chapters 15, 20, and 21. The term asbestosis should be reserved for the diffuse parenchymal lung disease that occurs as a result of asbestos exposure. A characteristic finding of asbestos exposure is the ferruginous body, a rod-shaped body with clubbed ends (Fig. 10-4) that appears yellow-brown in stained tissue. Ferruginous bodies represent asbestos fibers that have been coated by macrophages with an iron-protein complex. Although large numbers of these structures are commonly seen by light microscopy in patients with asbestosis, not all such coated fibers are asbestos, and ferruginous bodies may be seen even in the absence of parenchymal lung disease. Uncoated asbestos fibers, which are long and narrow, cannot be seen by light microscopy and require electron microscopy for detection.

Diffuse Parenchymal Lung Diseases Associated with Known Etiologic Agents

Diseases Caused by Inhaled Inorganic Dusts

Silicosis

Coal Worker’s Pneumoconiosis

Asbestosis

Diffuse Parenchymal Lung Diseases Associated with Known Etiologic Agents