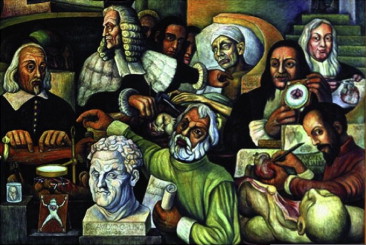

The fresco by Diego Rivera (1886 to 1957) on the history of cardiology was displayed at the “Instituto Nacional de Cardiología” of Mexico City at the time of inauguration on April 14, 1944. Some of the most important masters of the Padua Medical School were depicted, namely Vesalius, Harvey, and Morgagni. There is a vivid description of the anatomoclinical method introduced by Giovanni Battista Morgagni (1682 to 1771), when he was professor of Theoretical Medicine first and then of Anatomy at the University of Padua (1711 to 1771). By reading Morgagni’s De sedibus, we found the case of aortic syphilitic aneurysm that corresponds perfectly with the one represented in Diego Rivera’s mural. In the Museum of Pathological Anatomy of the Padua University, an anatomical specimen that displays the same lesion is preserved, and we have performed a computed tomography scan to analyze the state of the heart and aneurysm, thus finding diffuse calcific deposits of aorta and pericardium. In conclusion, in Diego Rivera’s fresco the clinicopathologic method of Morgagni is well represented and the case of syphilitic aneurysm, reported by Morgagni in his De sedibus , depicted.

The fresco by Diego Rivera (1886 to 1957) on the history of cardiology, displayed at the “Instituto Nacional de Cardiología” of Mexico City, has been the object of some papers recently published in medical journals. Rivera’s mural consists of 2 large panels of 6 × 4 m, which has been completed for the inauguration of the new Institute Building on April 14, 1944. They display the history of cardiology with its most famous masters depicted in significant contexts and actions.

Giovanni Battista Morgagni (1682 to 1771) is represented with his left index finger pointing to the chest of a dying patient with a pulsating aortic aneurysm below the left clavicle, in the upper side of the sternum. His right hand is holding a scalpel and showing the aneurysm found at the autopsy ( Figure 1 ). Also, Andreas Vesalius (1514 to 1564), the father of modern anatomy, is represented with a heart and aorta in his left hand. In the case of Vesalius, the organ is anatomically normal, whereas the aorta revealed by Morgagni is pathologically enlarged, as to underline the different research areas of the 2 scientists.

The case herein illustrated represents the essence of anatomoclinical correlation, which is the method used by Morgagni in his De sedibus et causis morborum per anatomen indagatis (The Seat and Causes of Diseases Investigated by Anatomy, 1761). In his work, Morgagni reported nearly 700 clinical histories trying to correlate clinical symptoms of living patients with morphologic substrates found at autopsy. Morgagni can be considered as the founder of physiopathology using anatomoclinical correlations as a model of the interpretation of the processes responsible for the lesions in the organ and the respective clinical manifestations.

In Rivera’s fresco, Morgagni is standing between William Harvey (1578 to 1657) and Marcello Malpighi (1628 to 1694), which could mean that he applied their teachings on pathology. He interpreted Harvey’s theory of blood circulation with the mechanical terms of Malpighi (iatromechanism), who conceived blood as a collection of particles and the body as a set of mechanical tubes, engines, and implements.

By reading the De sedibus , we have found the case that corresponds perfectly with the one represented in the mural. The case, reported in the Anatomo-Medical Letter XXVI , concerns

A man, particularly devoted to play bowls and wine, was affected by pain at both arms and fever. Soon after, a tumour similar to a big pimple manifested at the superior part of the sternum. […] When the patient was admitted to the Hospital for Incurables, this tumour was starting to ooze blood. […] The death occurred for an enormous shedding of blood.

During the autopsy, Morgagni found the following lesion:

In the chest a big aneurism was discovered. It was formed by an expansion of the anterior wall of aortic arch and partly destroyed the sternum and the extremity of clavicle placed on this bone, as well as the nearby ribs. Where the bones were consumed, nothing remained of artery tunica.

As depicted by Rivera, the site of the aneurysm, in both living patient and autopsied body, corresponds to the one described by Morgagni. In particular, Rivera shows Morgagni while dissecting an aneurysm located in the aortic arch, exactly as in the case of De sedibus herein reported. According to Morgagni, these cases were due to some “stinging” and “corrosive” particles circulating in the blood and by its unnatural pressure of nervous origin. Morgagni failed to relate these aneurysms with syphilis, probably because the mechanical explanation was enough.

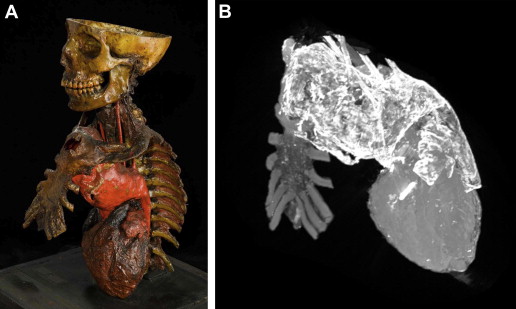

An anatomical specimen that displays the same lesion is preserved in the Museum of Pathological Anatomy of Padua University ( Figure 2 ). It is a trunk of a body with heart and great vessels conserved with the method of “tannization”. It consisted in an injection of tannic acid, which was invented by Lodovico Brunetti (1813 to 1899), first professor of Pathological Anatomy in Padua (1855 to 1887). We performed a computed tomography scan to analyze the internal state of the heart and aneurysm ( Figure 2 ). The aneurysm was located about 173 mm from the aortic annulus, affecting the ascending aorta, the aortic arch, and the first part of the descending aorta. The aneurysm has a maximum axial diameter of 80 × 80 mm and a craniocaudal diameter of 138 mm. At the retrosternal level, the aneurysm adhered to the sternal manubrium, causing a complete erosion of an area of about 70 mm in the axial plane and 42 mm in the craniocaudal, and involving the left the sternoclavicular joint, between the sternum and the first rib. The aneurysm sac came out in front of the sternum for about 37 mm, where it had a hole of 32 mm. A second hole of the axial dimensions of about 60 mm and craniocaudal of 52 mm was recognized at 41 mm from the aortic annulus in the retrosternal seat.