Fig. 15.1

Denis Jourdanet (1815–1892). By permission of the Wellcome Trust

It is therefore remarkable that in spite of Jourdanet’s groundbreaking idea as acknowledged by Bert (Fig. 15.2), very little about Jourdanet has been published. Apparently there is no full description of the man and his work in English. There are two or three biographical articles in French or Spanish but these do not discuss his scientific contributions. The aim of this paper is to redress this omission and show that Jourdanet was an innovative scientist as well as a successful physician, and that his contributions should be better known.

15.2 Brief Biography

This section is based on the account by Duffau [8–10] with additions from Auvinet [1] and Auvinet and Briulet [2]. Denis Jourdanet (1815–1892) (Fig. 15.1) was born in Juillan near Tarbes in the Hautes-Pyrénées, France, on May 1. As a young boy he was influenced by his uncle who was a village priest and he became very interested in the study of Latin. At the age of 13 he entered the Petit Séminaire de Saint Pé in Bigorre in the Hautes-Pyrénées where he remained from 1828 to 1833 and demonstrated a lively intellect. After a period in the college d’Aire he moved to Paris with his cousin Antoine where he began to study medicine. He enjoyed the contact with patients but not the formal lectures. Furthermore according to his biographer, Father Duffau, he had a preference for the easy life of the salons. In 1842 at the age of 26 before he had finished his medical studies, he decided to seek his fortune in America and on February 15 he embarked on the ship Arago at Le Havre for Mexico. He reached Veracruz on April 10.

Apparently his plans were vague and he was short of money, but fortunately he was helped by a representative of Yucatan in Veracruz by the name of Don José Dolores Castro. As a result he went to Campeche in the Yucatan Peninsula where his knowledge of medicine attracted many patients and he rather prematurely set up a medical practice in spite of the fact that this was not authorized. However an operation for cataract surgery (sic) impressed the French consul, A. Laisné of Villévêque, and as a result he was given the necessary legal authorization to practice medicine.

Jourdanet was subsequently accepted into the society of wealthy people, and his situation suddenly changed for the better when he married Señorita Rita Estrada, a daughter of Jose Maria Gutierrez de Estrada. This family enjoyed a special status in Campeche. Gutierrez Estrada was a prominent diplomat who had been a Secretary for Foreign Affairs of Mexico. Jourdanet therefore happily found himself to be the son-in-law in a family of considerable wealth.

In 1846 Jourdanet returned to Paris with his new wife where he was able to complete his formal study of medicine at the Sorbonne. He was influenced by the famous French toxicologist, Mathieu Orfila and his thesis dealt with the prevention and treatment of tetanus. His wife who had been affected by pulmonary tuberculosis for 12 years noted a definite improvement in her disease during her stay in Paris. Her brother had died of the same disease in 1847.

In 1848 the couple returned to Mexico but they decided not to live in Campeche where the tropical climate worsened the health of his wife. They therefore moved to Puebla, altitude 2200 m, southeast of Mexico City. Here Jourdanet began to develop what became one of his primary interests, that is the beneficial effects of altitude on some diseases. He made a series of measurements of barometric pressure at various increasing altitudes including the summit of the volcano La Malinche, altitude 4461 m. He came to the conclusion that the increased altitude of the high plateau improved his wife’s health and this led him later to write extensively on the value of a reduced barometric pressure in the treatment of disease.

In 1851 after 2 years in Puebla, Jourdanet moved to Mexico City, also at an altitude of about 2200 m. There he became a member of the Faculty of Medicine of Mexico and earned his second title of Doctor of Medicine. He also founded a Franco-Mexican college in an imposing colonial building known as the House of the Masks. This enabled French teachers to educate the children of French families who had settled in Mexico. There were occasional serious outbreaks of cholera in Mexico City and Jourdanet’s reputation increased as he dealt with these. His patients included several celebrities, and one was the successful businessman, Manuel Escandón, who generously rewarded Jourdanet for his services.

Unfortunately Jourdanet’s wife died in 1859 and he decided to return to France. In 1860 in Paris he had an opportunity to discuss his new findings at a meeting of the French Academy of Medicine. However he had a mixed reception. He argued that residence at an increased altitude could contribute to health and his first article on the topic was published in 1861 [14]. He also discussed his concept of what he called anoxyhémie where he drew a comparison between the physiological effects of anemia at sea level on the one hand, and reduced oxygen levels at high altitude on the other. This led him to promote the use of low-pressure chambers in the treatment of some illnesses. These topics are discussed below.

At this time Jourdanet became involved in politics. There was considerable tension between Mexico and its creditors, chiefly France, Britain, Spain and the United States, because interest payments had been suspended by the Mexican president. The problem was discussed at the Convention of London of 1861 and ultimately led to a French campaign beginning in 1862. Jourdanet was summoned to the Tuileries Palace by the Emperor Napoleon III to discuss the situation, and Jourdanet’s father-in-law headed a Mexican commission to Archduke Maximilian of Austria who was subsequently crowned as the Emperor of Mexico. Maximilian invited Jourdanet to be his personal physician but Jourdanet declined.

Jourdanet returned to Mexico in 1864 and continued his clinical work. His 1861 book [14] was renamed and was consulted by many officers of the Franco-Mexican troops on the effects of altitude on health. As a result of this service to the armed forces, Jourdanet was awarded the Cross of the Legion of Honor.

Jourdanet remarried in 1865, again into a wealthy family. His new wife was Señorita Juana Beistegui y García, daughter of a prominent owner of silver mines. Her sister, Loreto, subsequently married Alphonse Dano who was the Minister Plenipotentiary of France in Mexico. The two families continued to maintain close links. The Jourdanets left for France in 1867 after the defeat of the French troops in Mexico, and the execution of Maximilian. They returned to Paris and took an apartment on the Champs Elysées.

At this point Jourdanet decided to leave the practice of medicine and concentrate on science. At the Sorbonne he met Paul Bert who was 18 years his junior and the two developed a collaboration that resulted in the dedication of Paul Bert’s magnum opus as cited earlier. Jourdanet who was now wealthy financed Bert’s extensive laboratory in the Sorbonne where most of his work on the effects of high altitude was carried out. He also subsidized the publication of Bert’s book [3].

In 1875 Jourdanet found himself associated with the tragic flight of the French balloon “Zenith” with the three aeronauts, Tissandier, Croce-Spinelli and Sivel. The balloon reached an altitude of about 8600 m resulting in the deaths of the last two from hypoxia. Bert had previously learned that the balloonists had insufficient oxygen, and he tried to warn them about this but the warning letter arrived too late. The disaster caused a sensation in France. Jourdanet had witnessed the rapid ascent of the balloon and reported that he felt serious misgivings about the flight.

15.3 Jourdanet’s High Altitude Studies

Jourdanet’s high altitude studies were reported by him in several articles and books [14–20, 22]. However his most important publication was Influence de la pression de l’air sur la vie de l’homme in two volumes published by Masson in Paris, 1875 (Fig. 15.3). This is a very handsome production with many beautiful engravings and a number of colored maps. Each volume is divided into five parts each consisting of several chapters which themselves are comprised of several numbered “articles”. There is also an appendix and some supplementary notes. A second edition was issued in 1876. The entire first edition is available on the Internet. This digitized copy is from the Countway Library in Cambridge, MA, and includes a note at the beginning from Jourdanet with his signature.

Fig. 15.3

Title page of Jourdanet’s major publication “Influence de la pression de l’air sur la vie de l’Homme” [22]

The book begins with a long historical introduction on the physics of the atmosphere starting with Aristotle who speculated on the weight of the air. The contributions of Galileo, Torricelli, von Guericke and several others are then described but, perhaps betraying its French origin, the only engraving besides Galileo is a fine one of Blaise Pascal. There is also a section on the Loi de Mariotte which many of us know as Boyle’s Law. Entertainingly, Pascal estimated the total weight of the atmosphere at about 8 × 1018 livres (about the same in English pounds). There is a discussion of the properties of the atmosphere including the relations between temperature and altitude and the amount of water vapor. This is followed by a short, rather speculative chapter on possible changes in the atmosphere over geological time.

There is a long section on geography including altitudes of many places in the world. Facing page 85 there is a beautiful engraving showing what is purported to be Mt. Everest based on an aquarelle made by Hermann Schlagintweit in 1855 (Fig. 15.4). The altitude of the summit is given as 8816 m which is puzzling because Schlagintweit gave a value of 29,000 ft corresponding to 8839 m. The modern accepted value is close to this being 8848 m. However it is notable that in Appendix 1 of Bert’s La Pression Barométrique, Bert gives a table of the heights of mountains and the associated barometric pressures which he says is based on Jourdanet’s data. Mt. Everest is shown to have an altitude of 8840 m with a barometric pressure of 248 mm Hg. This is very close to the accepted value of about 250 mm Hg. Actual measurements on the summit by climbers in good weather when the pressure tends to be high are 253 mm Hg [33].

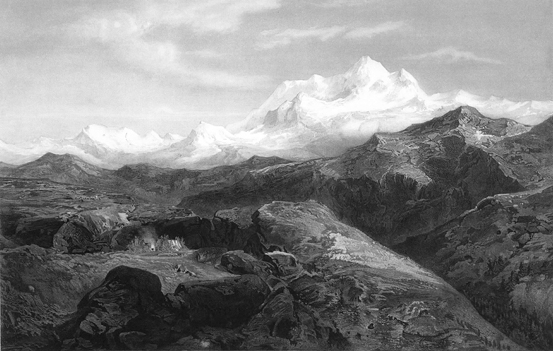

Fig. 15.4

Aquarelle by Hermann Schlagintweit dated June 1855 of what was thought to be Everest but is probably Makalu. An engraving of this is facing page 85 in Jourdanet’s major book. Schlagintweit gave the altitude as 29,000 ft which is very close to the actual value. This is one of the first images of this section of the Himalayan range. From [22]

There is a very long section with extensive tables on the altitudes of many high places in the world. This is followed by an extended section on Mexico including its geography and the number of inhabitants in various regions.

Jourdanet then turns to the medical and physiological effects of going to high altitude. First he describes in some detail the results obtained by Paul Bert in his low-pressure chambers. By exposing various animals to air at low barometric pressures on the one hand (hypobaric hypoxia) and low concentrations of oxygen at normal pressure (normobaric hypoxia) on the other, Bert was able to show the critical role of the partial pressure of oxygen. Also Bert was the first physiologist to measure the oxygen dissociation curve of blood under physiological conditions. There are descriptions of some of Bert’s experiments where he exposed humans including himself to low pressures in his chambers although Jourdanet points out that Bert himself never went to high altitude.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree