Patients presenting with suspected ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) may have important alternative diagnoses (e.g., aortic dissection, pulmonary emboli) or safety concerns for STEMI management (e.g., head trauma). Computed tomographic (CT) scanning may help in identifying these alternative diagnoses but may also needlessly delay primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). We analyzed the ACTIVATE-SF Registry, which consists of consecutive patients with a clinical diagnosis of STEMI admitted to the emergency departments of 2 urban hospitals. Of 410 patients with a suspected diagnosis of STEMI, 45 (11%) underwent CT scanning before primary PCI. Presenting electrocardiograms, baseline risk factors, and presence of an angiographic culprit vessel were similar in those with and without CT scanning before PCI. Only 2 (4%) of these CT scans changed clinical management by identifying a stroke. Patients who underwent CT scanning had far longer door-to-balloon times (median 166 vs 75 minutes, p <0.001) and higher in-hospital mortality (20% vs 7.8%, p = 0.006). After multivariate adjustment, CT scanning in the emergency department before primary PCI remained independently associated with longer door-to-balloon times (100% longer, 95% confidence interval 60 to 160, p <0.001) but was no longer associated with mortality (odds ratio 1.4, p = 0.5). In conclusion, CT scanning before primary PCI rarely changed management and was associated with significant delays in door-to-balloon times. More judicious use of CT scanning should be considered.

Door-to-balloon time <90 minutes in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) is associated with decreased mortality and is a key hospital quality measurement. With this emphasis on timely reperfusion, the decision to perform primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) must be made rapidly. However, in the appropriate clinical context, alternative diagnoses in patients presenting with STEs, including aortic dissection and pulmonary embolism, may bear consideration before coronary angiography. In addition, patients presenting with STEs and concurrent trauma may require emergency evaluation for intracranial or other sources of bleeding before intensive anticoagulation typically required during primary PCI. Although computed tomographic (CT) scanning may resolve these diagnostic dilemmas, this additional test delays timely application of primary PCI. To our knowledge, no previous study has examined the association between CT scanning and door-to-balloon time or outcomes in patients with suspected STEMI. The aim of this study was to analyze use of CT scans in the emergency department before primary PCI and to shed light on associated delays.

Methods

The ACTIVATE-SF Registry consists of consecutive patients with a clinical diagnosis of STEMI admitted to emergency departments of a tertiary care hospital (University of California, San Francisco) and an urban trauma center (San Francisco General Hospital) in San Francisco from October 2008 through April 2011.

Inclusion criteria and data collection processes of the ACTIVATE-SF Registry have previously been reported. Briefly, the 2 hospitals have a centralized paging system for autonomous emergency physician activation of the cardiac catheterization laboratory for primary PCI. All emergency physician-initiated STEMI activations during the study period were recorded and comprise the study population of this analysis. The inciting STEMI electrocardiograms (i.e., the electrocardiogram that led to the decision to activate the catheterization laboratory) were de-identified and reread for key variables by 2 cardiologists blinded to clinical outcomes. Laboratory values and angiographic and echocardiographic data were collected from electronic medical records. A waiver of consent was obtained from the institutional review board at the University of California, San Francisco (number 10-02615). Study data were collected and managed using Research Electronic Data Capture electronic data capture tools hosted at the University of California, San Francisco.

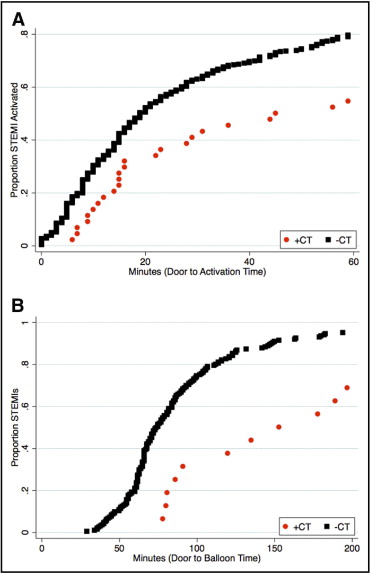

To better understand the effect of CT scan use on door-to-balloon time, we divided the overall door-to-balloon time into (1) door-to-STEMI activation time (door-to-activation time), (2) time from STEMI activation to patient arrival in the catheterization laboratory (activation-to-laboratory time), and (3) procedural time from catheterization laboratory arrival to reperfusion (laboratory-to-balloon time). Univariate analyses were performed using chi-square test for categorical and binary data or Student’s t test for continuous data. Multivariate linear regression models were developed to explore the contribution of CT scanning to door-to-activation time and door-to-balloon time using a manual backward-stepwise procedure. Covariates were locked in the model a priori if likely confounders or selected using a directed acyclic graph based on clinical knowledge and previous studies. Time outcomes (in minutes) were log-transformed for use in regression models to maintain normality. In-hospital mortality was also examined using nearest-neighbor propensity matching of baseline covariates to adjust for selection bias in the decision to perform CT scanning. Variables in multivariate and propensity matching algorithms were typical symptoms of angina, age, presentation with cardiac arrest, intubation, heart rate on presentation, systolic blood pressure, body mass index, history of coronary artery disease, and millimeters of STE on electrocardiogram. All statistical analysis was performed using STATA 11.2 (STATA Corp., College Station, Texas). All authors had full access to, and take full responsibility for, the integrity of the data. All authors have read and agree to the report as written.

Results

Of total population of 410 patients initially activated for primary PCI, 45 patients (11%) received underwent CT scan in the emergency department. There was no significant difference in CT use rates between the 2 hospitals. Compared to those who did not undergo CT scanning, patients who underwent CT scanning were more likely to have had a cardiac arrest and were more likely to be intubated ( Table 1 ). CT scanning was performed to rule out intracranial process (n = 19, 42%), aortic dissection (n = 18, 40%), pulmonary embolus (n = 3, 7%), acute abdominal process (n = 1, 2%), and trauma-related injury (n = 4, 9%). In total, only 2 of 45 (4%) CT scans led to a change in clinical management. Specifically, 2 head CT scans showed significant strokes (1 ischemic, 1 hemorrhagic) that led to cancelation of cardiac catheterization. In 1 case, the patient was obtunded on presentation; in the other case, the patient presented with syncope and unilateral weakness. None of the CT scans for suspected aortic dissection or pulmonary embolism was positive.

| Variable | CT Scanning | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | ||

| (n = 45) | (n = 365) | ||

| Men | 37 (82%) | 264 (72%) | 0.07 |

| Age (years), mean ± SD | 63 ± 14 | 60 ± 15 | 0.27 |

| Race | 0.13 | ||

| White non-Hispanic | 22 (49%) | 134 (37%) | |

| Asian | 8 (18%) | 96 (26%) | |

| African-American | 9 (20%) | 64 (18%) | |

| White Hispanic | 1 (2%) | 51 (14%) | |

| Other | 5 (11%) | 17 (5%) | |

| Body mass index (kg/m 2 ), mean ± SD | 26 ± 4.8 | 27 ± 5.6 | 0.36 |

| Baseline creatinine (mg/dl) | 1.40 ± 1.73 | 1.28 ± 1.06 | 0.50 |

| Emergency department presentation | |||

| Typical ischemic symptom ⁎ | 15 (33%) | 213 (58%) | 0.001 |

| Cardiac arrest | 16 (36%) | 54 (15%) | 0.001 |

| Intubated | 14 (31%) | 45 (12%) | 0.001 |

| Systolic blood pressure <100 mm Hg | 8 (18%) | 53 (15%) | 0.56 |

| Pressor requirement | 10 (22%) | 47 (13%) | 0.30 |

| Heart rate <50 beats/min | 1 (2%) | 21 (6%) | 0.26 |

| Off-hours presentation | 28 (62%) | 228 (62%) | 0.98 |

| Emergency department doctor with >10 years’ experience | 22 (49%) | 192 (53%) | 0.64 |

| Translator required † | 10 (22%) | 71 (19%) | 0.69 |

| Brought by ambulance | 30 (67%) | 203 (56%) | 0.13 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 11 (24%) | 83 (23%) | 0.69 |

| Hypertension ‡ | 23 (51%) | 190 (52%) | 0.86 |

| Dyslipidemia ‡ | 13 (29%) | 108 (30%) | 0.89 |

| Any previous coronary disease | 14 (31%) | 118 (32%) | 0.87 |

| Active smoker | 12 (27%) | 135 (37%) | 0.19 |

| Active drug abuse | 12 (27%) | 51 (14%) | 0.04 |

| Electrocardiographic characteristics | |||

| Primary territory with ST-segment elevations | 0.22 | ||

| Anterior | 21 (47%) | 170 (47%) | |

| Lateral | 4 (9%) | 23 (6%) | |

| Inferior | 8 (18%) | 108 (30%) | |

| Posterior | 4 (9%) | 12 (3%) | |

| None | 7 (16%) | 49 (14%) | |

| Left bundle branch block | 2 (4%) | 24 (7%) | 0.58 |

| Mean height of ST-segment elevation (mm), mean ± SD | 2.4 ± 3.1 | 2.3 ± 2.1 | 0.82 |

| Mean number of leads with ST-segment elevation on electrocardiogram, mean ± SD | 2.6 ± 2.2 | 2.7 ± 2.2 | 0.59 |

| Coronary angiographic findings | |||

| Culprit lesion present § | 22 (49%) | 212 (58%) | 0.78 |

| Culprit vessel | 0.9 | ||

| Left main coronary artery | 0 (0%) | 3 (1%) | |

| Left anterior descending coronary artery | 10 (44%) | 97 (45%) | |

| Left circumflex coronary artery | 5 (19%) | 29 (14%) | |

| Right coronary artery | 6 (33%) | 76 (36%) | |

⁎ Typical ischemic symptom was any chest pain, discomfort, or pressure.

† Defined as need for a translator while the patient was in the emergency room.

‡ Hypertension and dyslipidemia were defined as present if they were identified as part of the medical history by the responsible emergency physician.

§ Any thrombotic total or subtotal occlusion of a coronary artery.

Emergency department electrocardiograms were not significantly different between patients who did and did not undergo CT scanning before catheterization (mean 2.4 vs 2.3 mm maximal STE, p = 0.82; 2.6 vs 2.7 leads with diagnostic STEs, p = 0.59). After activation of the cardiac catheterization laboratory, a larger percentage of patients who underwent CT scanning were not taken to cardiac catheterization (14 [31%] vs 55 [15%], p = 0.002). Most cancelations of cardiac catheterization were due to the cardiology team deciding that the clinical presentation was not consistent with STEMI ( Table 2 ). Of patients who did undergo coronary angiography, those who underwent CT scanning had a similar rate of culprit coronary lesions on angiogram (60% vs 61%, p = 0.83). There was no significant difference between groups in anatomic distribution of the culprit vessel.

| Type of CT Scan | Primary PCI Canceled Owing to CT Scan Results |

|---|---|

| All computed tomograms | 2/45 (4%) |

| Head computed tomogram | 2/19 (11%) |

| Dissection protocol | 0/18 (0%) |

| Pulmonary embolism protocol | 0/4 (0%) |

| Trauma series | 0/3 (0%) |

| Abdominal computed tomogram | 0/1 (0%) |

Patients who underwent CT scanning before catheterization had a longer door-to-activation time (median 51 vs 19 minutes, p = 0.001) and a longer door-to-balloon time (median 166 vs 75 minutes, p <0.001; Figure 1 ). A door-to-balloon <90 minutes was achieved in only 5 patients (19%) with culprit lesions who underwent CT scanning compared to 130 patients (63%) who did not (p <0.001; Table 3 ). After multivariable adjustment, CT scanning in the emergency department before primary PCI remained independently associated with longer door-to-activation times (110% longer, 95% confidence interval [CI] +40 to +205, p = 0.001) and door-to-balloon times (100% longer, 95% CI +60 to +160, p <0.001).