Degenerative Valve Disease-Calcific Aortic Stenosis and Mitral Annular Calcification

Allen P. Burke, M.D.

Joseph J. Maleszewski, M.D.

Introduction

Degenerative aortic valve disease extensively involves the cusps themselves and results in fibrotic thickening and nodular calcification. Inflammation and neovascularization are not dominant features, in distinction to rheumatic valve disease. Degenerative calcification has a propensity for congenitally bicuspid or unicuspid valves and usually causes stenosis with variable insufficiency.1 Degenerative aortic stenosis is currently the most common indication for valve surgery, as the population ages and newer techniques, such as minimally invasive surgery and transcutaneous methods, become available (see Chapter 178).

Degenerative Aortic Stenosis (Tricuspid Valve)

Aortic sclerosis, which is clinically defined as valve thickening without obstruction to outflow, is present in about 25% of patients over 65 years of age, who have tricuspid valves. The incidence of symptomatic stenosis is ˜5 in 10,000 and is generally a disease of the elderly. Risk factors overlap with those predisposing to atherosclerosis, and hypertension, smoking, diabetes, and obesity.1,4,5 The role of hyperlipidemia and statin treatment in the prevention of aortic stenosis is unclear, although hypercholesterolemia is an often-cited risk factor.4,6

Clinical Findings

Patients with calcific degenerative aortic stenosis present in the 6th to 9th decades and account for more than 70% of the patients undergoing valve replacement in the United States. Those patients with tricuspid valves are usually older than 65 to 70 years. Patients with chronic renal failure and secondary hyperparathyroidism have symptomatic disease at an earlier age, because of an increased risk for tissue calcification.7

There is a male predominance ranging from 1.6:1 to 4:1, depending on etiology. Clinically, most patients have stenosis or combined stenosis and insufficiency. The natural history of aortic stenosis is characterized by a prolonged period in which the disease is only incidentally detected. During the initial phases, the left ventricle adapts to the increased systolic pressure overload and develops hypertrophy with normal chamber volume. This is followed by concentric left ventricular hypertrophy, which may cause reduced coronary blood flow and subendocardial ischemia, even in the absence of epicardial coronary disease. Eventually, symptoms of angina, syncope, and heart failure develop. The development of symptoms usually signifies advanced disease with hemodynamic compromise.

Gross Pathologic Findings

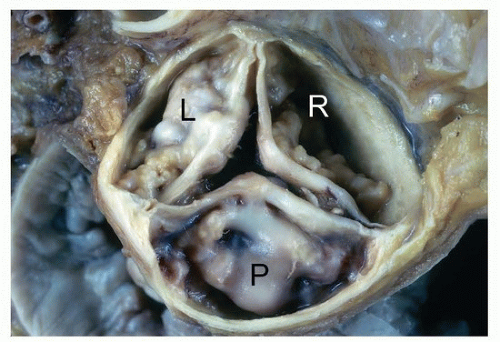

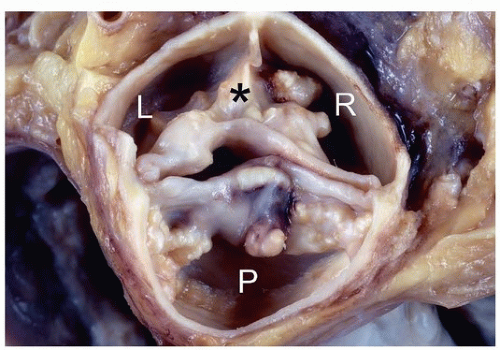

Degenerative calcific aortic valve disease is characterized by nodules of calcification on the aortic (nonflow) side of the cusps, usually near the base of the sinuses (Fig. 172.1). The degree of stenosis at autopsy is estimated by assessing the stiffness of the valves, as by palpation or passage of an instrument or finger through the opening the outflow tract, though only when concentric left ventricular hypertrophy is present should one presume stenosis was present.

The evaluation should also document degree and location of calcified deposits, presence of median raphe that would indicate a congenitally bicuspid valve (Fig. 172.2), commissural fusion, intimal calcification of the ascending aorta (Fig. 172.3), and evaluation of the aortic root for signs of dilatation. Occasionally, mild fusion of one or more commissures may be seen in the setting of degenerative sclerosis, but it is usually less than half way to the midpoint of the cusp free edge, distinguishing it from chronic rheumatic valve disease.

Heart weight and measurements of left ventricular free wall and left ventricular chamber diameter (excluding papillary muscles) are important to document the degree of cardiac hypertrophy and remodeling. In about 5% of patients, there is asymmetric hypertrophy with an increase in septal to free wall ratio. There is frequently coexistent atherosclerosis of the coronary arteries and calcification of the mitral annulus.

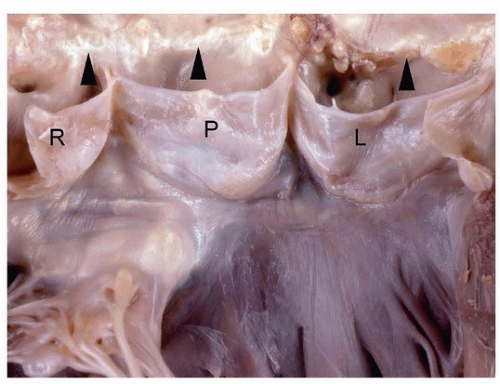

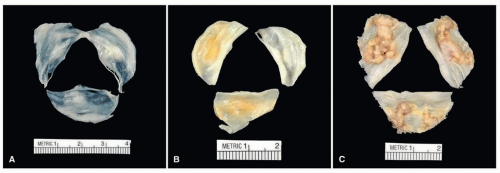

Normally, aortic valve cusps should be thin and translucent (Fig. 172.4A). As part of the degenerative process, aortic valve cusps become increasingly thickened until they are no longer translucent (Fig. 172.4B) and can be considered sclerotic. Surgically excised valves for nodular calcific aortic stenosis may be fragmented during surgical procedure due to heavy calcification, or the valve cusps may be relatively intact (Fig. 172.4C). The calcification begins in the base of the cusp and spares the free margins; thus, commissural fusion is rare but may occur (Fig. 172.5). Gross inspection and documentation of degree of calcification are sufficient for a diagnosis of degenerative calcific aortic disease. Endocarditis is an infrequent complication of calcific aortic stenosis but can be easily missed without histologic evaluation.

The presence of calcification is an important determinant of the degree of stenosis or gradient measured clinically.8

Microscopic Findings

The histologic findings include nodules of calcification at the base of the cusps on the aortic surface, which occur on pools of fibrin, similar to nodular calcified plaques seen in nodular calcific deposits in coronary and carotid atherosclerosis (Fig. 172.6). In addition to nodular calcification, there is mild chronic inflammation.9,10 The sparse inflammation is composed of macrophages, plasma cells, and lymphocytes. If there are dense macrophage infiltrates or any neutrophilic inflammation, then superimposed endocarditis should be excluded by special stains or clinical correlation. Rarely, small foci of neutrophils may be identified adjacent to calcific deposits.

In the myocardium of patients with left ventricular hypertrophy secondary to aortic stenosis, the amount of myocardial fibrosis has been shown to affect long-term survival after aortic valve replacement.11

Treatment

The standard treatment for aortic stenosis is surgical replacement of the valve, with or without coronary artery bypass surgery for coronary atherosclerotic obstruction, which is commonly present. The operative mortality is 2% to 5%.12

Patients who are inoperable, due to functional status or ascending aortic calcification, may be treated by balloon valvuloplasty or transcatheter aortic valve replacement. The 5-year survival after

either procedure is < 25%.13 Transcatheter aortic valve implantation is performed with balloon-expandable or self-expandable valves (see Chapter 41).14

either procedure is < 25%.13 Transcatheter aortic valve implantation is performed with balloon-expandable or self-expandable valves (see Chapter 41).14

Degenerative Aortic Stenosis, Bicuspid Aortic Valve

Bicuspid Aortic Valve, General Aspects

Congenitally bicuspid aortic valve is present in about 1% to 2% of the population. There is male predominance of up to 4:1. Familial studies suggest that congenital bicuspid aortic valves follow autosomal dominant inheritance patterns with reduced penetrance. Congenitally bicuspid aortic valves are over 20 times more likely to become stenotic than normally formed aortic valves, and calcify at a younger age.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree