Chapter 1

Definitions and policy

Joshua B. Kayser1, Kim Mooney-Doyle2 and Paul N. Lanken1

1Pulmonary, Allergy and Critical Care Division, Dept of Medicine, Dept of Medical Ethics and Health Policy, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA. 2Centers for Global Women’s Health and Health Equity Research, University of Pennsylvania School of Nursing, Philadelphia, PA, USA.

Correspondence: Joshua B. Kayser, Pulmonary, Allergy and Critical Care Division, Dept of Medicine, Dept of Medical Ethics and Health Policy, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Cpl. Michael J. Crescenz Veterans Administration Medical Center, 3900 Woodland Ave, 8B115, Philadelphia, PA 19104, USA. E-mail: joshua.kayser@va.gov

Palliative care aims to provide enhanced quality of life for patients with serious and life-limiting illnesses. It thus focuses on controlling symptoms and supporting patients and family caregivers. Palliative care is a patient-/family-centred multidisciplinary process based on the ethical principles of beneficence (benefiting the patient) and respect for the patient’s dignity and autonomy (self-determination). Palliative care should maximise quality of life for patients with advanced stages of respiratory diseases in the months, or even years, preceding death, and should reflect the preferences of patients and their families relating to how, where and when death will occur. Palliative care for patients with respiratory diseases can be challenging. Such patients have clinical courses that may vary from a prolonged recurrent waxing and waning course to a rapidly downhill course. Additionally, patients with advanced respiratory diseases may require repeated hospitalisations, including the need for aggressive LSTs with assisted ventilation in ICUs. This necessitates discussions and decisions related to withholding and withdrawing life support. Because differences in national and local cultures impact clinical practices in forgoing life support, the decision making process regarding the latter should take into account the relevant cultural context. This is especially important when considering the creation and adaptation of global healthcare policy in palliative care.

This chapter introduces the subject of providing PEOLC to patients with respiratory diseases. It includes descriptions of recent epidemiology related to respiratory illness and dying and death, a brief history of palliative care and hospices, definitions of commonly used terms in discussions of PEOLC (table 1), relevant bioethical context and models of decision making among healthcare providers and patients and families, and how palliative care is provided. Finally, it also characterises global variations in PEOLC with the aim of better understanding global policy efforts to improve the delivery and outcomes of palliative care.

Table 1. Terms and definitions related to PEOLC

Palliative care | From the 2002 WHO definition [1], palliative care is the active total care that aims to improve the quality of life of patients, and their families, with progressive, life-limiting illness through the prevention and relief of suffering by means of impeccable assessment and treatment of pain and other problems, such as physical, psychosocial and spiritual. Palliative care may be incorporated alongside disease-directed treatments from the point of diagnosis. It aims to help patients live as actively as possible until the time of their death, and helps family carers cope during the illness and after death into bereavement. Palliative care may be provided by all clinicians caring for patients with progressive disease in all health and social care settings, at least with regard to basic skills, with specialists able to provide care for those with complex and persistent problems. The provision of palliative care is in response to patient and carer concerns rather than requiring a prognostic trigger in relation to estimated time of death. Domains of palliative care include supportive care, advance care planning, EOL care (care in the last months of life), care of the dying and bereavement care. |

Specialist palliative care | A multiprofessional clinical specialty in which health and social care professionals are identified as having special competence in the field of palliative care and this is their core business; palliative medicine specialists may be board certified in certain countries. Specialist palliative care may be provided in hospitals, community settings or stand-alone palliative care units (which may be called specialised palliative care units or hospices). |

Hospice care | This is a term used variably in different countries. In the UK, it is generally used to describe a specialist palliative care unit that provides inpatient care beds and a variety of community and outpatient services. Patients may be referred according to need rather than prognosis, and can access inpatient spells for assessment and management of acute complex symptoms with consequent discharge home, or respite, or care of the dying. Patients continue to be able to access the full range of clinical support available on the National Health Service. In the USA, “hospice” usually refers to community-based specialist palliative care focused on relief of symptoms for patients in advanced stages of their illness and support for their family carers, e.g. more likely than not expected to result in death within a few months. |

Supportive care | Symptomatic treatment of the different forms of suffering and pain including physical, spiritual, emotional, psychological and moral distress throughout the illness from pre-diagnosis. |

EOL or terminal care | Care of patients with life-limiting diseases preceding death. Variable time periods are used to define EOL, e.g. in the UK it refers to the last 12 months of life and in the USA typically to the last 6 months of life. |

Care of the dying | Care of actively dying patients with focus on relief of suffering and maximising dignity in the last hours or days of life. |

Bereavement care | Supportive care for family and friends who are grieving the loss of their loved ones. |

Definitions in this table draw on the 2002 World Health Organization (WHO) definition of palliative care [1] and a systematic review by VAN MECHELEN et al. [2]. | |

Epidemiology of PEOLC

Few things in life are certain, but one undeniable truth is that everyone who lives ultimately dies. The National Vital Statistics Report for deaths in the USA indicates that nearly 2.6 million deaths were registered in the USA in 2013 [3]. The corresponding estimated number of deaths worldwide at that time was 55 million [4]. However, while the inevitability of death is unfailing, time has transformed the human experience of how one dies. Throughout much of recorded history, death was random and unpredictable, afflicting people of all ages. Most died at home, commonly of infectious diseases. In recent history, with the advent of public health efforts, such as sanitation, vaccination and the use of antibiotics, death has become more predictable, preferentially afflicting the very young and the elderly. In the industrialised world, infection has been supplanted by cancer and chronic illness as the primary causes of death. For example, as of 2013, infection, (specifically influenza and pneumonia) ranked as the eighth leading cause of death in the USA with its associated 57 000 deaths representing <5% of the 1.3 million deaths attributed to heart disease, cancer and chronic lower respiratory diseases, which were the top three causes of death in the USA in 2013. Sepsis was the only other infectious cause of death to rank in the top 15 [3]. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), all communicable diseases combined only account for ∼25% of all deaths worldwide [5]. By comparison, the WHO fact sheet on CRD indicated there are over 65 million people worldwide living with moderate to severe COPD, corresponding to over 3 million deaths (5%) annually [6]. In their report on noncommunicable diseases in 2010, they predicted a 15% global increase in all noncommunicable disease deaths between 2010 and 2020 [7]. These statistics suggest that, in the present and future, far more patients will struggle with chronic, progressive illness for extended periods prior to ultimately succumbing to their disease than in the past.

Another notable trend over the past 50 years relates to how medical care is provided and where death occurs. Few patients receive healthcare directly in their homes, as was common in previous centuries. Additionally, life-sustaining technologies have shifted the location of death for many people to healthcare institutions. In essence, disease and death have become less communal. Sick patients often seek medical care in isolation and are far more likely to die in hospitals, with the focus on curative rather than palliative interventions. This change in location associated with nonpalliative goals of care may reflect how various societies and cultures generally regard sickness and the dying process, i.e. events not to be witnessed or even discussed.

However, the patient experiences of living with disease and the dying process have occurred without conversations among stakeholders about the manner in which care should be provided to support patients and families with serious and advanced diseases and how that care should be funded. Indeed, funding for PEOLC is often limited, and may be structured such that choosing a primarily palliative approach may dictate that patients forgo simultaneous curative or restorative interventions. The Worldwide Palliative Care Alliance estimated that over 20 million people (i.e. 37% of all deaths worldwide) could benefit from palliative care, with the vast majority (69%) being adults of 60 years of age or older. Although utilisation of palliative care is rapidly increasing, the growth is predominantly in industrialised societies, specifically in European, Western Pacific and North American regions [5]. Not only is the growth of palliative care less robust in other areas of the world, but, importantly, these increases in utilisation do not take into account the timing of palliative care. Significant variability exists in terms of providing supportive care for patients living with chronic illness as opposed to EOL care for patients dying of their disease. As such, the potential exists not only to expand palliative care efforts in less economically advanced regions of the world but also to ensure efforts to provide high-quality supportive care and symptom relief in addition to ensuring that patients receive appropriate and desired care at the EOL.

It has been over a decade since ANGUS et al. [8] first described the epidemiology of EOL care in the USA in 1999: one in five Americans died in an ICU and nearly 40% of all USA deaths occurred in a hospital. In light of the ageing US population, this portended a future shortfall in hospital and ICU capacity. In the intervening years, it is difficult to argue that much has changed. For example, according to US Medicare data from a 2013 publication by TENO et al. [9], although the number of deaths in hospitals decreased by 8% between 2000 and 2009, ICU utilisation by patients in their last month of life increased by 5%. Similarly, although hospice enrolment doubled over that time period, nearly two-thirds of those enrollees utilised hospice services for fewer than 4 days. Additionally, 40% of hospice referrals were preceded by ICU hospitalisation and were accompanied by numerous transitions of care in the last 3 days of life, again acknowledging the lack of early integration of palliative care prior to the EOL [9].

These statistics are not unique to the USA. A 2016 study by BEKELMAN et al. [10] retrospectively compared site of death, healthcare utilisation and hospital costs for patients of 65 years of age of older dying with cancer in 2010 in seven North American and European countries. They found that a range of 40–50% of patients in the non-US countries died in acute care hospitals (versus 22.2% in the USA) [10]. However, non-US patients were far less likely than US patients to utilise the ICU in the last 180 days of life (<18% versus 40.3%, respectively), with hospital expenditures ranging from around US $9000 to US $22 000 per capita [10].

The statistics are similarly sobering with regard to the lack of early palliative care to relieve the burdens of disease that exist prior to the EOL. For example, a 2010 study comparing COPD and cancer patients demonstrated that patients with COPD had similar disease burdens to cancer patients but survived five times longer (median survival 107 days in cancer versus 589 days in COPD), meaning that COPD patients suffer from symptoms of disease for years leading up to death [11]. Unfortunately, attempts to improve symptoms of respiratory illness in the years preceding death, in particular breathlessness, the defining characteristic of respiratory disease, have garnered insufficient attention when compared with efforts to improve EOL care [12]. While both are tremendously important, it will be critical for leaders of the field of respiratory medicine to ensure that any advancements in the provision of high-quality EOL care are accompanied by efforts to integrate palliative care earlier in disease in order to minimise burdens and enhance quality of life.

History and models of palliative care

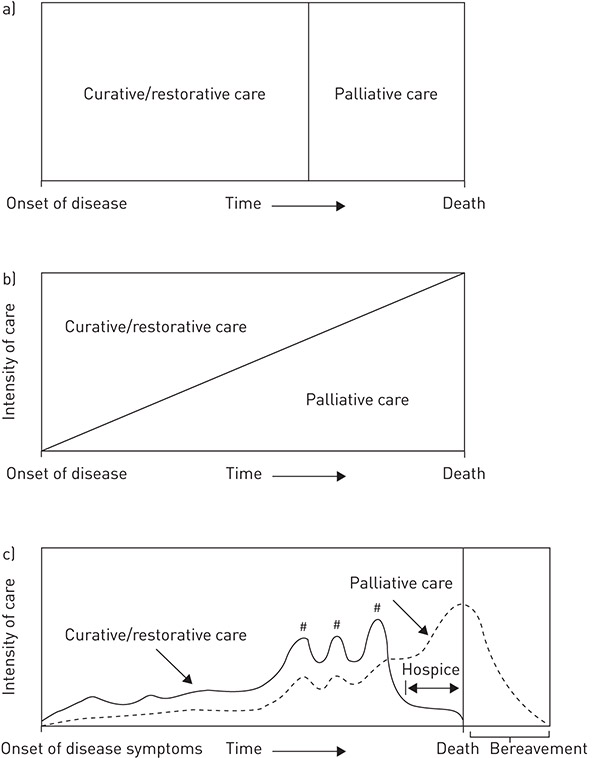

The term “palliative care” was coined in 1973 by Balfour Mount, a Surgeon of the Royal Victoria Hospital in Montreal, Canada [13], and may be defined as a focus on the relief of suffering in patients with serious and advanced illness (table 1). In practice, palliative care providers seek to maximise quality of life for such patients and their families or other caregivers. A common misconception is that palliative care is synonymous with hospice or EOL care, when in fact palliative care is not limited to the terminally ill and can occur in parallel to curative and life-prolonging treatments (figure 1). The field of palliative care developed as a response to societal changes, resulting in the idea that death could be prevented, obscured or controlled, rather than being the natural order of things. Early practitioners of palliative care sought to re-emphasise and recognise death as an acceptable and natural outcome rather than a failure, and to focus primarily on relief of suffering rather than cure of disease [16].

Figure 1. Schematic models of palliative care in relation to provision of curative or restorative care. a) Traditional dichotomous model, i.e. “all or nothing”, in terms of the period of providing only curative/restorative care followed by the period of providing only palliative care. b) Overlapping model. c) Individualised model. #: periods of high intensity curative/restorative care, such as hospitalisations for lower respiratory tract infections. Reproduced and modified from [14] with permission. Originally modified from [15].

Although not synonymous with hospice care, the origins of the practice of palliative care can be traced back to the hospice movement, which began in the 1960s. The term “hospice” originates from the Latin word hospitium, meaning hospitality. Descriptions of the first hospices as places of care for the dying can be found in texts from medieval times. The history of modern hospice and palliative medicine is equally rich. In 1969, Elisabeth Kübler-Ross, a Swiss–American psychiatrist, published her seminal work, On Death and Dying, within which she first categorised five stages of grief and underscored the inadequate consideration given to suffering at the EOL [17]. Around the same time, Cicely Saunders, both a nurse and a physician, established St Christopher’s Hospice in London, UK. She would later go on to write another influential book, Living with Dying: a Guide to Palliative Care, published in 1995 [18]. The first American hospice was established by the nurse Florence Wald in 1974 in New Haven, CT, USA. This was followed by the first palliative medicine programme introduced by Balfour Mount in Montreal in 1975. 12 years later, in 1987, hospice and palliative medicine became recognised as an official medical specialty in the UK, followed by numerous countries around the world. It took nearly 20 more years before the USA finally established hospice and palliative medicine as a medical specialty in 2006 [16].

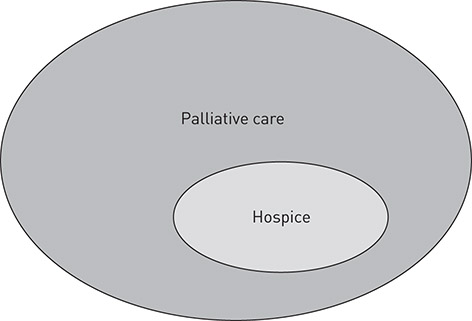

Goals of palliative care and hospice

If the goal of a hospice is to provide relief of suffering and support to patients and their families at the EOL, then palliative care can be seen as an expansion of the early hospice movement to develop similar comprehensive support services and enhance the quality of life for those with advanced disease over the intervening months or even years preceding death (figure 2). In the last decade, numerous international societies have published guidelines and recommendations for the provision of palliative care, including the American Thoracic Society [14], the Society of Critical Care Medicine [19] and the American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine [20]. Recently in the USA, the Institute of Medicine issued a report detailing the state of healthcare for patients dying in the USA, and included substantive recommendations for the approach to death and dying in the future, including early integration of palliative care into routine healthcare for patients with advanced diseases to improve quality of life and death, as illustrated in figure 1c [14, 21]. Similar statements and guidelines have been published by institutions in other countries, including the European Respiratory Society and European Society of Intensive Care Medicine [22–25]. All of these organisations have advocated for improved communication and adoption of a shared decision making model for patients with advanced illness. Shared decision making is a collective process of communication between clinicians and the patient or surrogates to determine what decisions need to be made, to engage in dialogue to clarify preferences, to ensure understanding medical interventions and to achieve consensus in those decisions [26–28].

Figure 2. Hospice care is a component of a broader palliative care approach to serious respiratory illnesses.

Ethical principles of medical decision making

For physicians and other healthcare professionals, medical decision making has been closely linked to the professional obligation to adhere to the four core principles of bioethics: autonomy, beneficence, non-maleficence and justice. In Western civilisation, autonomy, derived from the Greek autos (“self”) and nomos (“law”) [29], has traditionally been seen as the pre-eminent principle among the four. Autonomy can be defined as the right of a patient to be the primary determinant of what medical interventions and treatments he or she will receive: in essence, the right to self-determination, including the right of refusal. Beneficence refers to the ethical duty for medical professionals to promote the well-being of their patients, which dates from Hippocratic times. Non-maleficence, the corollary of beneficence, is embodied in the traditional maxim primum non nocere (“first do no harm”). Lastly, justice refers to the fair distribution of healthcare, and the essence of the principle of distributive justice arises from the Greek philosopher Aristotle’s formal annunciation: “Equals must be treated equally, and unequals must be treated unequally” [30]. These four guiding principles provide a practical ethical framework to aid in the medical decision making process. However, in practice, these principles often come into conflict with each other (e.g. providing beneficent care may not respect a patient’s autonomy). Furthermore, the complexities of modern medical practice, in particular when dealing with vulnerable populations, such as patients with advanced and terminal respiratory illness, have prompted some ethicists to argue for an expansion of the ethical lens through which we view decision making beyond the four basic ethical principles [31]. Additional duties include the obligations to communicate effectively, to provide culturally competent care and to understand the patient experience in sickness, including the nature of suffering. In this respect, palliative care providers may possess a unique skill set with which to explore this expanded template.

Medical decision making

The spectrum of medical decision making extends from the directed or paternalistic model of the physician as decision maker at one end to the informative, autonomy-driven model of physician as information provider with the patient or surrogate making EOL decisions at the other end (table 2). Shared decision making falls within these two bookends, with variable degrees of collaboration between provider and patient or surrogate. Experts have argued that good shared decision making necessitates that healthcare providers understand where patients and caregivers fall along this continuum to improve outcomes [32, 33]. Studies of surrogate decision making preferences suggest that there is wide variability in terms of families’ preferences in decision making roles [34], and that failure to identify preferences and tailor decision making accordingly may result in an increased risk of adverse consequences such as post-traumatic stress disorder among surrogates [35].

Table 2. Models of medical decision making according to roles of the physician and patient or patient’s surrogate during the three stages of the decision making process

Stages of decision making process | Model of medical decision making | ||

Paternalistic | Shared | Informed | |

Information exchange | One-way flow of information from physician to patient/surrogate | Two-way flow of information to/from physician and patient/surrogate | One-way flow of information from physician to patient/surrogate |

Deliberation | Physician alone | Physician and patient/surrogate | Patient/surrogate alone |

Deciding on treatment to implement | Physician | Physician and patient/surrogate | Patient/surrogate |

Reproduced and modified from [27] with permission. | |||

While patients in the outpatient setting with respiratory diseases are able to participate in conversations about medical decision making, many patients in the ICU lack the capacity to make decisions and are therefore unable to participate in discussions [36]. In this context, responsibility falls on a surrogate decision maker to engage in conversations on behalf of the patient. The surrogate decision maker should preferentially use a substituted judgement standard if possible, and if not, a best-interests standard should be used.

Use of a substituted judgement standard assumes that the surrogate has knowledge of the patient’s values and preferences for or against certain medical interventions. These can be based either on explicit conversations with the patient, such as expressed in an advance directive, or by considering the patient’s life goals and values, as expressed in words or by prior healthcare decisions. Best-interests standard refers to making decisions on the patient’s behalf by comparing the benefits of an intervention against the burdens (pain, suffering, cost to patient and/or to patient’s family) of that intervention and by proceeding with the intervention if its benefits outweigh its burdens, while forgoing the intervention if its burdens outweigh its benefits. Best-interests decision making should be used when the surrogate does not have knowledge of the patient’s preferences or cannot infer such preferences as described above. A glossary of these and other terms related to bioethics and medical decision making are given in table 3.

Table 3. Glossary of terms related to bioethics and medical decision making

Term | Definition |

Autonomy | Bioethical principle referring to the informed and competent adult patient’s right to self-determination, respect for dignity and ability to refuse medical interventions and treatments |

Beneficence | Bioethical principle referring to the goal of medicine to provide relief from pain and suffering and for the duty of physicians, nurses and other healthcare providers to promote the well-being of patients |

Non-maleficence | Bioethical corollary to beneficence that healthcare providers have an ethical duty not to inflict harm on patients |

Justice | Bioethical principle related to fairness, most commonly in the distribution of limited or scarce resources |

Self-determination | The right of informed, competent adult patients to make choices based on their preferences for medical care |

Informed consent | The legal and ethical concept related to self-determination in which a competent, adult patient agrees to undergo a specific medical intervention after being provided relevant information about that intervention: its indication, objectives, risks, benefits and alternatives, including the alternative of no intervention |

Informed refusal | The legal and ethical concept related to self-determination in which a competent, adult patient refuses to undergo a specific medical intervention after being provided relevant information about that intervention: its indication, objectives, risks, benefits and alternatives, including the alternative of no intervention |

Informed assent | The concept that reflects the willingness of a non-competent patient (e.g. a child or minor, or an adult who has lost or never had decision making capacity) to undergo a specific medical or research intervention |

Substituted judgement | Bioethical principle referring to a surrogate decision maker making medical decisions for a patient who lacks sufficient capacity for decision making, based on knowledge of that patient’s previously written or verbally expressed preferences for medical treatment or of the patient’s values and life goals |

Best-interests standard | Bioethical principle referring to a surrogate decision maker who lacks knowledge of a patient’s preferences and who makes medical decisions for a patient who lacks sufficient capacity for decision making, based on a weighing of the benefits (e.g. life, quality of life, chances for survival) against the burdens (e.g. poor quality of life, financial costs, pain and suffering of patient and family) of a medical intervention and then making the decision on behalf of the patient after judging whether the benefits of the intervention outweigh its burdens (by choosing the intervention) or whether the burdens of the intervention outweigh the benefits (by forgoing the intervention) |

Physician-assisted suicide | Medical act of a physician that assists a patient to commit suicide, e.g. prescribing a potentially lethal dose of a medication for the patient to administer to themselves at a later date with the objective being to cause cessation of the patient’s life; this may be legal or illegal depending on state or country jurisdiction |

Euthanasia | The act of administering an agent for the primary purpose of causing the patient’s death |

Surrogate decision maker | An individual either appointed or otherwise identified by a patient or legal authorised representative who has the legal and ethical authority to make healthcare decisions for a patient in the event that the patient is unable to make medical decisions for themselves, i.e. the patient lacks sufficient decision making capacity |

Advance directive | Also known as a living will, this is a legal document in which a capable patient describes her or his preferences for medical care in advance of an illness that renders them incapable of making such decisions in the future |

LST | A treatment that is required to sustain organ function and hence life; also referred to as “life support” |

Paternalism | A traditional practice of physicians in which the physician makes medical decisions on behalf of the patient based on his or her expertise |

Patient-/family-centred care | Healthcare that actively engages patients and families to participate in decision making processes and seeks to provide healthcare in accord with the values and preferences of the patient and family; the patient identifies their family members, e.g. may be blood- or legal-relatives or friends |

Suffering | Physical or existential distress felt by patients and their families from illness or injury or in the process of medical care |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree